How Rudolph Valentino Invented Sex Appeal

It was a quiet funeral home in a respectable part of Manhattan, but on August 24, 1926, it was the improbable scene of a near riot. The turmoil broke out among thousands of women, mourning the death of actor Rudolph Valentino, as they attempted to rush the doors at Campbell’s Funeral Church. After several women broke through a large plate-glass window, police were called to the scene.

For the next few days, as contributor Beverly Smith Jr. noted in his Post article “Farewell, Great Lover” (January 20, 1962), the police had their hands full controlling the line of women—estimates vary between 30,000 and 100,000—who waited to file past Valentino’s mortal remains. In a time of mass excitements, he wrote, the Valentino craze lasted longer than most among “the nation’s more susceptible womenfolk, from flappers to grandmothers.”

The surging crowds at Campbell’s gave America its first glimpse at the modern celebrity cult. Until then, America had known actors and musicians who could draw large crowds, but no one had been able to draw so many fans for so many days.

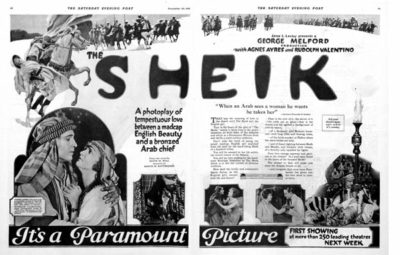

The Valentino craze began 91 years ago this month, with the premier of The Sheik. Today, it seems like a prehistoric, overacted piece of melodrama. Yet it still offers a vivid reflection of American society as it entered the modern age.

It was remarkably successful, earning $1 million in its first year—five times more than what it cost to produce.

Just as reflective of the year 1921, though, is how the movie became so profitable. The Sheik didn’t work the same old melodramatic formula, offering women another charming hero in another predictable romance. Instead it gave them Hollywood’s first male sex symbol.

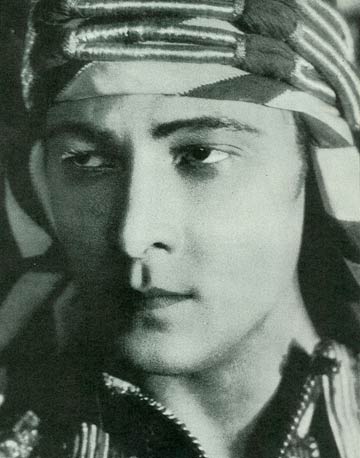

Rudolph Valentino (i.e., Rodolfo Alfonzo Raffaello Pierre Filibert Guglielmi Di Valentina d’Antonguolla) was an Italian immigrant who’d worked his way across the country with odd jobs, eventually winding up as a ballroom dancer in California. His tango skills helped him land a role in The Four Horsemen of Apocalypse in 1920. The film was a hit, principally due to Valentino’s success in portraying an impulsive, fiery, headstrong “Latin lover.” Later that year, he was chosen to play another exotic lover: Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan.

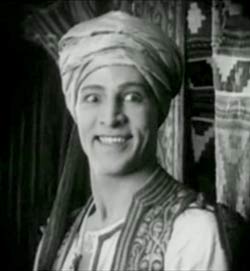

Three minutes into the movie, as Valentino appeared before his tent, happily supervising the sale of wives to his tribesmen, many American women began to reconsider their choice of daydreams. Suddenly the old romantic heroes—the rugged lawman, sensitive poet, laughing cavalier, or wealthy sophisticate—were demoted by Valentino’s ability to smolder, pose, look imperious, and break into a boyish grin.

Years later, actress Bette Davis recalled, “A whole generation of females wanted to ride off into a sandy paradise with him.” But the Sheik’s paradise wasn’t about sharing poetry and soulful looks while holding hands. It was about sex.

The novel, on which the movie was based, concerned a willful aristocrat, Lady Diana Mayo, who sets out to explore the Algerian desert with no company but an Arab guide. Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan spies her and, within a chapter, abducts her and rapes her. But apparently it’s all right because Lady Mayo falls in love with him by the end of the book.

The novel is not explicit about the rape, but it leaves the reader in little doubt. (“Her whole body was one agonized ache from the brutal hands that forced her to compliance,” chapter three, The Sheik, Edith Hull, 1919.) The movie is even more careful to avoid direct reference to sexual assault, but the implications are as subtle as a billboard:

“Why have you brought me here?” Lady Mayo demands of the Sheik in his tent.

He replies. “Are you not woman enough to know?” (See accompanying leer at right.)

The movie played to the liberated spirit of the 1920s. It was the perfect entertainment for a carefree, reckless age. It appealed to women who were celebrating the modern freedoms, the new fashions of the Flapper, bootleg liquor, hot jazz, and the permissiveness to “pet” in the boyfriend’s roadster far in a dark lane, far from parents’ supervision.

The movie also reflected a changing attitude among American men. For the most part, they hated the new male sex symbol, having already committed themselves to the styles of Douglas Fairbanks or Tom Mix. But other men saw the future of American romance in Valentino’s polished, sensual manner and hurried to climb onto the bandwagon. They copied Valentino’s world-weary languor, his smooth manners, his passionate lovemaking, and his thoroughly oiled hair.

Lastly, but unfortunately, the Sheik represents the ambient racism that Americans had come to expect from popular entertainment of the 1920s.

In the book and movie, much is made about the forbidden love between an Arab and a “white woman.” Even love could not be allowed to overcome the social divide of Arab and European. But any plot that worked so hard to unite the lovers could find a convenient solution. The Sheik, it was revealed at last, was not “Arab” but as “white” as Lady Mayo. He had been adopted by the Ben Hassan tribe as a youngster, but was nonetheless the child of an English father and Spanish mother. The happy ending could now proceed. While some women could forgive abduction and assault in 1921, no one felt comfortable with interracial romance.

It might have been the modern age, but American society hadn’t come that far.