The Remarkably Boring Signing of the Treaty of Versailles

Statesmen, soldiers, and civilians alike anticipated the official end of the Great War. Since the armistice of November 1918, Allied forces had occupied the Rhineland, and negotiations about what to do with Germany were ongoing. The war had stopped, but it threatened to resume at any time if a peace treaty wasn’t signed. Some Germans even insisted they’d make a comeback.

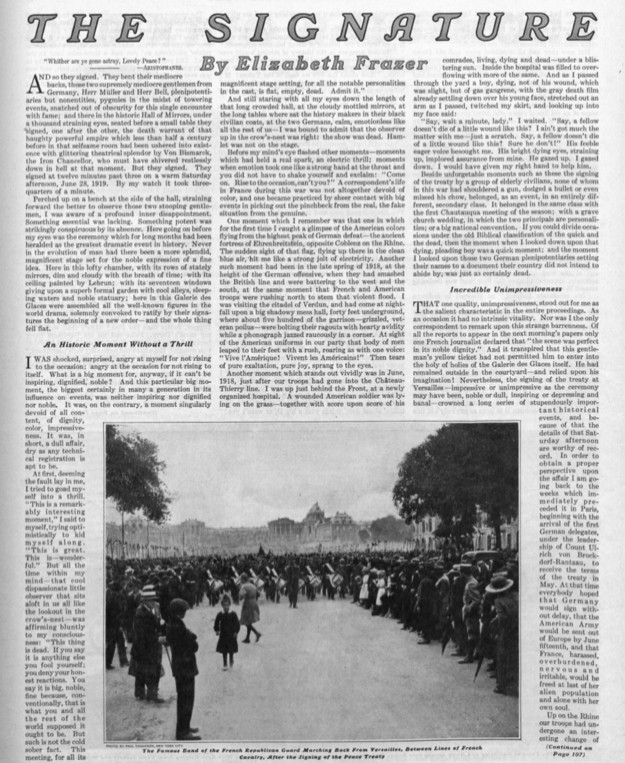

One of the The Saturday Evening Post’s war correspondents, Elizabeth Frazer, reported on the combat in France and Germany for years, and she was situated in Versailles to witness the climactic moment: the signing of the peace treaty. Only, it wasn’t climactic. In fact, Frazer described the 45-minute affair as “an historic moment without a thrill.”

Her story, “The Signature,” was published 100 years ago in this magazine, and it is one of the most detailed personal accounts of the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Frazer’s report resounds not because it gives a play-by-play of the famous meeting of world powers in 1919 — although it does. Her story’s significance shines through in its depiction of the complex nature of peace after years of life in wartime. After reporting on the front lines at Château-Thierry and witnessing an American flag flying from the Ehrenbreitstein fortress, Frazer found herself let down by the ceremony that ended all of the excitement: “I was shocked, surprised, angry at myself for not rising to the occasion; angry at the occasion for not rising to itself. What is a big moment for, anyway, if it can’t be inspiring, dignified, noble? And this particular big moment, the biggest certainly in many a generation in its influence on events, was neither inspiring nor dignified nor noble.”

When she entered the Galerie des Glaces in Versailles, the air was “heavy, turgid, overcharged” and the room was filled with the manic energy of a restless and lawless crowd. Even as French Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau gave a short speech and the signing began (first the Germans, then Wilson, Great Britain, etc.), Frazer claims the chatter in the room never completely quieted. “The final signatures were affixed, Clémenceau pronounced the séance at the end, the Germans slipped out quietly, and the other delegates with laughter and congratulations filed out into the garden,” she writes.

The most historically significant part of Frazer’s report is, perhaps, after she left Versailles to go back to her apartment — and her “aide-de-camp” — in Paris. A working-class Parisienne named Friant assisted the journalist with travel, accommodations, and translation. The woman had lost two sons to the war and was awaiting the return of her third when Frazer returned to give her the news of peace. Frazer requested Friant’s company at dinner and for the entire serving staff to join them to hear the events of the day: “François, tell the waiters on the floor to slip in when they have a moment, and I’ll tell them all about the ceremony today at Versailles before it is out in the papers. This was your war. Every one of you fought in it. Most of you were wounded. And now this is your peace.”

As they dined on a dove of peace (pigeonneau en cocotte) and Chambertin wine, Frazer heard from the waitstaff their own experiences during the war, and assured Friant — once again — that perhaps her long-lost son would be found. “They discussed France, the future, their fears. For they were all afraid. They were afraid of the power of Germany, her determination to wipe them out. This League of Nations — how, literally, would it protect them?” Why had the ceremony been so dead, she wondered, and the French workers assured her that it was because the signing of peace only held gravity so much as the world leaders involved could hold to their word.

It was “because there was no romance,” said Friant, “bald-headed elderly civilians in black coats and hats for the chief actors.” Or, according to Jean, a socialist server, “because the real people were not there. They were sweeping out mademoiselle’s room and smoking a secret cigarette on the stair.” As Frazer’s time as a correspondent in the country came to an end, she found the meat of the Great War’s politics and consequences in a humble flat surrounded by an array of Parisian proletariat instead of under the ornate, gilded ceiling of the gallery in Versailles.

Featured image: Versailles. Réunion du comité interalliés, Helen Johns Kirtland, 1919, Library of Congress.