The 1969 Draft Lottery Didn’t Solve Nixon’s Problems

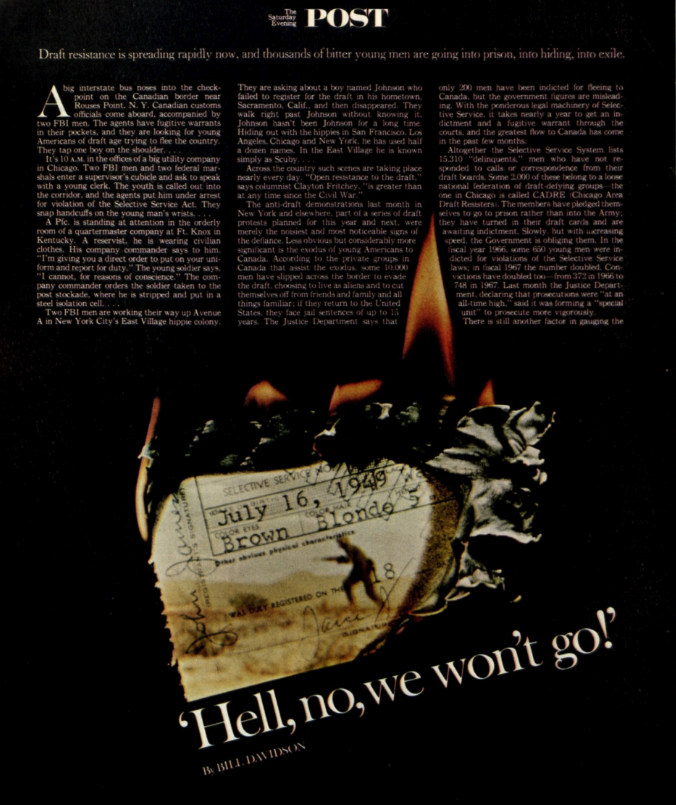

At the height of the Vietnam War, perhaps no stateside military issue caused as much friction as the draft. There was certainly already a groundswell of antiwar sentiment. The Saturday Evening Post ran an article on draft resistance called “Hell, No, We Won’t Go!” in the January 27, 1968 issue; the cover even depicted a burning draft card. The dislike for the random nature of the draft would only get worse in the days before and after the December 1, 1969, draft lottery drawing, which happened 50 years ago this week.

The draft had already been cited as an unfair process, and many Americans weren’t happy with the ongoing escalation of the country’s involvement in the war. With troop levels jumping from 82,000 in-country in 1965 to 500,000 by 1967, there didn’t seem to be much of an end in sight. Other social movements, like the hippie counterculture and the Civil Rights movement, began to intersect with anti-war activism, prompting louder and louder calls to end the U.S.’s role in the conflict.

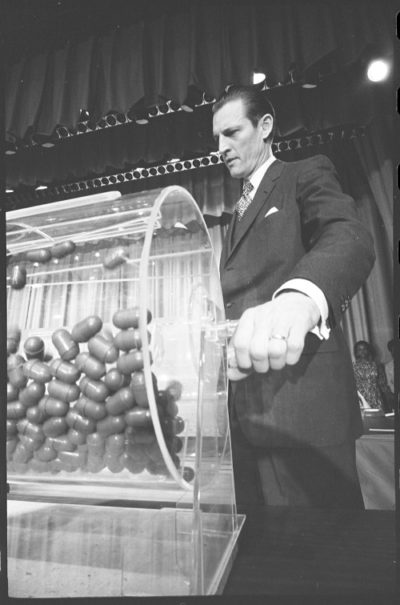

President Richard Nixon sat in the center of it all. When he took office in January of 1969, he had publicly expressed a desire to begin a drawdown in troop levels. However, he wanted to achieve some kind of solution that brought Americans home, ensure the security of South Vietnam, avoid the appearance of a U.S. “loss” in any way, and move the U.S. military to a volunteer force; it was basically an impossible task. On November 26, 1969, Congress moved to modify part of the Military Selective Service Act of 1967; that adjustment gave the president the authority to change how the draft worked. That same day, Nixon issued Executive Order 11497, which allowed for random selection, or a draft lottery. It was held on December 1, 1969.

The lottery worked by putting every day of the year (including February 29) onto individual slips of paper and then packing each paper into a plastic capsule. The capsules were mixed in a shoebox, poured into a jar, and then drawn one at a time. The first drawn number was 258, which corresponded to September 14, the 258th day of the year. That meant that all eligible men of draft age (that were born on September 14 during a span of years that ran from January 1, 1944 to December 31, 1950) would be called to serve at the same time. Deferments were available for draftees that were actively in college or deemed physically unable to serve; some registered for the National Guard in an effort to stay home and avoid active deployment overseas.

The Draft Lottery. (Uploaded to YouTube by AP Archive)

At the time of the draft, 850,000 young Americans were affected. Local draft boards, with a span of 18- to 26-year-olds in the eligible range, chose 19-year-olds first., altering an earlier rule in which the oldest end of the pool was chosen first. The lottery, which some took to be a fair, random way of selecting personnel, turned out to have all sorts of incongruities and problems, with some dates having a higher concentration of births and perceived inequities in selection at the local draft board level, since wealthier draftees were more likely to earn a deferment due to college enrollment. It actually exacerbated opposition to the war, according to books like Peace: A History of Movement and Ideas by David Cortright; Cortright wrote that Nixon’s own task force for exploring the volunteer army transition reported that draft resistance surged “at an alarming rate” in 1970.

As the war went on, Nixon juggled drawing down forces while trying to negotiate an end to hostilities. Drafts occurred in 1970, 1971, and 1972; they were set to expire in 1973 under the original provision of the order, but the January 1973 cease-fire agreement negated it entirely before the last draft would have happened. While 18-year-olds are still required to register for Selective Service, the military did segue to a volunteer force after the close of the Vietnam War.

Featured image: The Drafty Lottery of 1969. (Photo by Warren K. Leffler; LOC.gov)

John Lennon and Yoko Ono Took Peace Lying Down

John Lennon married Yoko Ono on March 20, 1969. For most couples, getting married in Gibraltar and honeymooning in Amsterdam would be a fine plan, but the then-Beatle and his artist/musician bride had bigger plans. From March 25 to March 31, Lennon and Ono conducted the first “bed-in” as a non-violent protest to war and an innovative way to spread their message of peace.

Anti-war activism hit a peak period in the late 1960s, with American involvement in the Vietnam War acting as a particular flashpoint for protests. The always outspoken Lennon had delved into more social issues after his pilgrimage to India and working on the so-called “White Album” in 1968. Ono also had strong anti-war beliefs and the pair began to lean into promoting their ideals in various ways.

The couple took advantage of the already prodigious interest in their wedding and extended invites to the press to meet them at their suite at the Amsterdam Hilton from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. every day from March 25 to March 31. Lennon and Ono simply sat in bed, wearing pajamas, with their backs to the window, signs hanging from the glass that read “Bed Peace” and “Hair Peace.” They used the forum to articulate their anti-war message and further other social causes.

A second bed-in occurred in Montreal in May. The original plan had been to hold it in New York City, but Lennon was temporarily unable to enter the U.S. due to his 1968 marijuana conviction. Eventually, they settled on seven days at Montreal’s Queen Elizabeth Hotel. A number of celebrity guests attended portions of this bed-in as well, including: TV star Tommy Smothers (of The Smothers Brothers); comedian and activist Dick Gregory; activist, writer, and LSD advocate Timothy Leary; L’il Abner creator Al Capp; DJ Murray the K; Beat poet Allen Ginsberg; musician Paul Williams, and more. Many of those guests joined Lennon and Ono in the recording of “Give Peace a Chance” from the room on June 1. The song, credited as a song-writing collaboration between Lennon and fellow Beatle Paul McCartney, would later be released as a single by Lennon and Ono’s group The Plastic Ono Band in July of 1969; the song would eventually hit #14 on the Hot 100 in America and #2 in the U.K.

Music video for “Give Peace a Chance.” (Uploaded to YouTube by johnlennon)

After the two bed-ins, Lennon and Ono went on to other demonstrations and projects to promote peace, and the song took on a life of its own, becoming an anthem for protestors in the months and years that followed. While Lennon was by no means the first nor last musician to speak out against the war, his extreme fame and the notoriety of the protests made him one of the faces of the movement. Lennon’s outspoken activism made him a target of the Nixon White House; as a result, Lennon had trouble securing permanent residency status in the U.S. until 1976. While the bed-ins inspired other artists and activists to mimic that particular set-up, their wider influence came from putting more of a focus on the peace movement in general. To this day, celebrities continue to participate in a variety of non-violent protests both in person and online, with personalities like Alyssa Milano (a major #MeToo movement advocate) and U2’s Bono being notable examples.

Featured Image: John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Amsterdam Bed-In. (Photo by Eric Koch for Anefo; Wikimedia Commons via Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.)

A Troubling View from Vietnam: 50 Years Ago

In the years since the Vietnam war, the U.S. has repeatedly sent its military into conflicts around the world. But the human and economic toll of these other conflicts is minor when compared with Vietnam.

In the years since the Vietnam war, the U.S. has repeatedly sent its military into conflicts around the world. But the human and economic toll of these other conflicts is minor when compared with Vietnam.

That war, which was still ramping up 50 years ago, brought about several changes in American thinking. The failure of the Vietnam mission forced the administration to reconsider how it would oppose communism. The endless, seemingly pointless deaths of recruits gave many draft-age Americans a hostile attitude toward their government and authority in general. This attitude, in turn, produced a rift between American youth and its elders. The older generation, which had brought victory to the U.S. in World War II, couldn’t recognize how much had changed in 25 years.

It was the members of that generation who were developing the strategy for the Vietnam War. They believed in the invincibility of our military and the inevitability of American victory. Their faith led them to keep pouring men and money into the fight that achieved little or no progress. By 1967, 8,694 Americans had died in the war, and it hadn’t even reached its hardest years. Before the U.S. withdrew from the country, another 38,000 Americans would be lost.

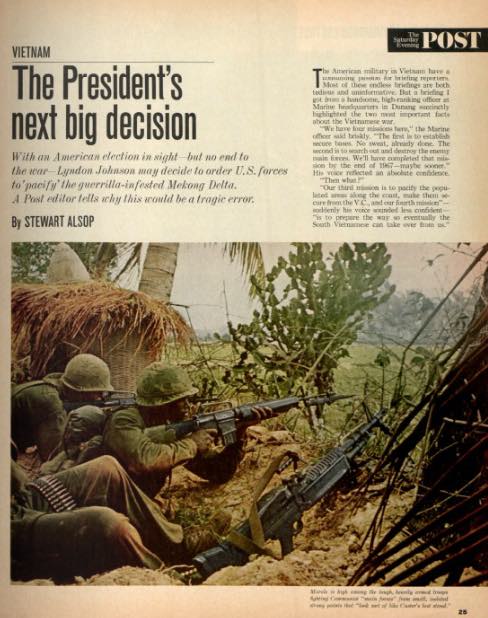

Not all military personnel were blind to the actual course of the war. You can hear some of their voices in the article “The President’s Next Big Decision,” from the March 25, 1967, issue of the Post. Reporter Stewart Alsop visited a vulnerable, isolated unit near the Demilitarized Zone with guns pointing in all directions. The Marine battalion commander who led him around commented, “Looks kind of like Custer’s last stand, doesn’t it?”

The article shows that some reporters and soldiers already saw that Vietnam wasn’t going to be the short, decisive, or victorious war that Washington expected.

Featured image: From “The President’s Next Big Decision” from the March 25, 1967, issue of the Post. Photo by Michel Renard

Vietnam Vets: ‘Why We Chose to Serve’

It’s not unusual for vets in uniform to be stopped by strangers and told how much their service is valued, especially around Veterans Day. But Americans weren’t always grateful to the men and women who served in the military. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, some treated Vietnam veterans with indifference or even blatant hostility.

The country had been generally supportive of the Vietnam War in its early days. An October 1965 Post survey found 65 percent of Americans ready to extend the Vietnam War another four to five years. And 59 percent were willing to escalate it, “even if it means bombing Hanoi and Red China.” But enthusiasm faded as the country learned the harsh realities of the fighting. In time, some Americans extended their resentment of the war to the men who were fighting it. The war became an uncomfortable fact, and its veterans were given scant recognition for their service.

Below, five Vietnam veterans share thoughts about service to country, the public’s reaction to their service, and how it shaped their thoughts on war today.

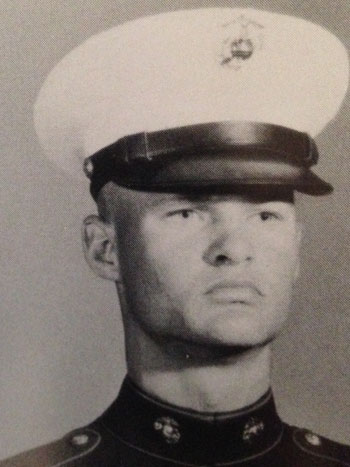

Charles Boland, Corporal, USMC

Making a choice: “I knew the chances were quite high that I’d be drafted, and I always wanted to be a Marine. … There is no other service with its history of the esprit de corps. When you enlist in the Marines, you’re changed forever.”

Public reactions: “I was wounded, evacuated, and sent home. … I remember being confronted by a woman. She asked me how I’d been hurt. When I told her I’d been wounded in Vietnam, she said, ‘I wish you’d been killed.’ Until then, I hadn’t been confronted by hatred.

“People walk up to you now and say, ‘Thanks for your service.’ But some vets get mad when they hear this. They tell me they get the feeling what’s really being said is ‘thank you for serving so I didn’t have to.’”

Serving the country: “Just paying your taxes is like buying a substitute to take your place in the Civil War. … I think there should a greater sense of service to country … in the Peace Corps, in communities, assisting other people, volunteering at VA hospitals to free up the staff, not just in the military.”

Reflecting on the war: “Too many people are willing to go to war at the drop of the hat. They’re not really willing to look at what’s going on.”

Dave Beyerlein, Infantry Sergeant, USMC

Making a choice: “I joined in March of 1966 with a buddy in Portland. The Marines grew me up and gave me respect for authority.”

Public reactions: “There was no respect for time spent and sacrifices made. We caught a lot of crap from people. At least one person called me a baby killer.

“It took decades for America’s thinking to come around so people could recognize that we [veterans] were just slobs who got caught in the war. Problem is, it took a lifetime to for that to happen.”

Serving the country: “I believe everyone should spend two years in service to our country. If you’re just along for a free ride, you don’t understand what you’re getting for free. It doesn’t have to be the military; it can be any service. But it gives you ownership. It will give you a different perspective and you’ll value your citizenship more.”

Reflecting on the war: “I’m so antiwar now it’s crazy. The war we were in was totally worthless. It was what, 58,000 dead? And now Vietnam’s one of our trading partners, and they’re still communist.”

Randolph Schiffer, First Lieutenant, USMC, Commander, USN Reserves

Making a choice: “For young men in America in the 1960s, the Vietnam War was the central issue. … I wanted to face this issue squarely. … I [joined the Marines] to make a statement to myself about duty, honor, and loyalty to country.”

Public reactions: “I was accepted at three top-tier medical schools before I went, but when I returned two of those three refused to reaccept me, as did seven others to which I applied. The sentiment in the medical schools was exemplified by the admissions committee feedback given to me in person by Harvard. ‘We’re not taking you because you’re a Vietnam veteran,’ they said. When I asked what specifically it was about the veteran part, they said, ‘We just don’t think a Vietnam veteran could do the work at Harvard Medical School.’

“There has been a complete inversion in Americans’ attitude toward veterans. People who return from the Mideast war can’t walk into a room without hearing ‘thanks for your service.’ I didn’t hear that when I came back in 1972.

“I believe what we’re seeing here is the national guilt and shame about the way they treated people like me in the 1960s. … Now I get admiration for my service, but it was a long road to getting it.”

Reflecting on the war: “Eisenhower said the most powerful military force is an aroused democracy. We don’t have that now. … The wealthy, powerful, and white, in many cases, are saying ‘I don’t want to serve in military.’ We have a professional military. It’s smaller and better paid, but not diverse enough to be representative of the country.”

Ted Decker, Corporal E4, USMC

Making a choice: “I’d decided that, if I was going to serve, I’d serve as a Marine … all the while knowing there was a good chance I was going to Vietnam. … I take great pride in it [my service]. But military life is not for everyone. We, as a nation, have to respect people who do that. It’s a hard life.”

Public reactions: “Back then, vets were looked on with disdain. Vets today are treated with more respect. I think we paid for it.”

Serving the country: “I had a chance to see different cultures, and I realized that ours is a great country. I didn’t appreciate the simple things until I had to do without them. … I think every young man or woman should spend at least a year in service, in some form, whether in the Peace Corps or some such organization.”

Reflecting on the war: “After the death and atrocities I’ve seen, I wonder why God spared me. I came close to death so many times. But when I look at my son and three grandsons, I know.

“I don’t think we should ever forget Vietnam. What that war did was make us a nation that’s afraid to act until it’s too late. We keep waiting and hoping things will get better.”

Andres Vaart, Captain, USMC

Making a choice: “I was an immigrant [from Estonia]. My mother and I were fortunate enough to get to the U.S. in 1950. I felt strongly that military service was the right thing, knowing what it was like to be occupied by Soviet Union. … I was interested in joining the Marines. I knew we’d be going to Vietnam, but I would be going into service to fight communism. It didn’t matter where.”

Serving the country: “To me, the idea of universal service to the nation is a very reasonable one, whether in the military or somewhere else.”

Reflecting on the war: “In those days, there was one big enemy. We got used to the big enemy we had to unify to oppose. Now I wonder if we got into that habit of thinking: We now leap to the idea of that one big thing, whether it’s the Chinese, Islam, or general terrorism.

“I sometimes wonder about the most powerful nation on earth being the most fearful nation. I think we should respond to challenges with something other than fear — rather a sense of acceptance and some confidence we know how to deal with problems.”