North Country Girl: Chapter 48 — The Accidental Model

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

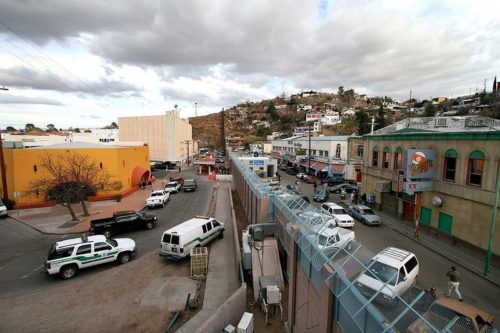

James and I were on our way back to Mexico, driving his El Dorado from Chicago to Acapulco, probably the only time a Cadillac has been used as economy transport. After escaping from the police in Dallas, it was a relief to finally see the signs telling us the Mexican border was near — no more Texas! At the border crossing we were greeted with no more than the usual stares at the sight of a forty-three-year-old man and a twenty-one-year-old blonde in a new El Dorado covered in a layer of Texas dust; border patrol officials on both sides spent more time looking at us than at our passports.

As soon as we crossed the border, James, who had driven though most of Texas, pulled to the side of the road, slumped over, and mumbled that he had to get some sleep. We switched seats, I took over the wheel, and I drove into bedlam. Gone were the smooth, well-maintained US highways. I had to swerve into the other lane or the shoulder to avoid potholes that would have swallowed up the Caddy. There were also: long stretches of road that no one had gotten around to paving, men on horseback, kids leading burros, cows, pick up trucks carrying gigantic, loosely tethered cargo, buses with people riding on the top, flatbed trucks with 60-foot logs rattling away, more cows, dead dogs covered with frightening black clouds of vultures, and barefoot vendors with peeled oranges, bags of soft drinks, tamales, back scratchers, and loose cigarettes, all standing way too close to oncoming traffic, and sometimes even in the middle of the road. All of these nightmares were shrouded in a smog of exhaust and dust particles that hovered a constant three feet off the ground.

I had a death clutch on the steering wheel, but managed to pry my right hand loose, reach over, and switch off Linda Ronstadt. Music was too much of a distraction, and how many times had I heard “Blue Bayou” on this trip already? It was just as hard to tear my eyes from the hellish road; when it finally seemed safe, a quick glance showed me a James dead to the world, snoring slightly, mouth dangling open, looking quite a bit older than forty-three. My eyes and hands and mind fixed to the task at hand.

I drove for hours, deep into the Sonoran desert, where the traffic and the villages thinned out and I realized I had been clenching my jaw and my sphincter way too tight. The sun was setting to my right, a golden yolk dropping behind distant hills, setting the desert on fire. For a few minutes, everything was lit like a J.M. Turner painting, only a lot more arid. But here was night, drawing across the sky like a dark blue blanket, and then everything went black. I turned on the headlights and quickly switched to high beams, which flickered weakly through the still settling dust.

I noticed that the El Dorado seemed to be the only car going in either direction that had a working pair of headlights. Most drivers felt that the light of the moon was all the illumination they needed, while some cars had a single, dim headlight; I had to guess if it was the right or left one. It was like an awful game of chicken in some black and white teen movie. I crept along as far to the right of the road as possible, hoping no one was out for a stroll along the highway at seven at night, till I saw the flickering of a Vacantes motel sign. I didn’t care about cleanliness, price, nothing. I wanted out of the car.

After a night spent in an iron bedstead and a breakfast of tortillas and beans washed down with Nescafé, I said to James, “I am never driving in Mexico, day or night, again.” James teased me as a coward, and did the day’s drive, which was uncannily identical to the one the day before, with as much aplomb as if he had been toodling down Chicago’s Lakeside Drive. But that evening, when James got to experience the odd penchant Mexicans have for driving through the pitch dark countryside with their headlights off, he surprised me by pulling into a motel after only eleven hours behind the wheel.

By late afternoon of our third day in Mexico, we were winding up the mountains behind Acapulco, chasing the last rays of sun vanishing off in the west. We crested the top, and there, slipping in and out of sight as we made the hairpin turns downward, was Acapulco Bay, just visible as a silvery gleam separate from the velvet sky, where a thousand lights sparkled. James sighed, smiled, and reached over to take my hand. We were back.

It only took a few hours for James to find a place for us. Our home for the next few months was not oceanfront; it was even farther up the hill than the apartment I had shared with the three French Canadian girls. The building looked like a motel. Three blocky two-bedroom units shared a single umbrella table, four lounge chairs, and a shallow little pool that did have an eye-popping view of Acapulco. The other two units stood strangely empty the entire time we lived there. Our rent included daily maid service. A tiny, silent woman came in every morning, made us coffee, cleaned the apartment, took away our dirty laundry, and always asked if we would like lunch. James couldn’t or wouldn’t think ahead to meals, but once she left us a plate of chicken sandwiches that was one of the most delicious things I have ever eaten.

James and I fell back into last winter’s languid pleasure-seeking days, with only a few modifications. His budget did not allow for a season’s membership at a private beach club or for daily water-skiing. James shrugged off these deprivations without losing too much of his self-esteem. “Next year,” he told me.

When I had first met James he could go days without checking his portfolio, confident that his stock picking acumen meant that there was nowhere to go but up. Now every morning we drove down to the Sheraton’s newsstand, where James bought yesterday’s New York Times, lit a cigarette, and nervously tore through the papers to the stock market quotes.

James’s mood depended on that day-old news. If his stocks were down, he was furious with frustration: he had no way of contacting his broker other than waiting in line for hours at the sweltering office of the inept Mexican telephone company to make a long distance call. On those bad days I could look forward to hours of James taking on all comers at backgammon at the Villa Vera. He believed he could recoup some of his stock market losses by gambling, and he was desperate to prove to himself that he was a winner. He did win a lot, having the sharpie’s eye for novice players who were easily scalped, or blowhards who James taunted into making stupid moves and accepting hopeless doubles. His obsession left no time for meals. I spent those days at the Villa Vera swim-up bar, trying to fill up on bullshots (vodka and beef consommé), and wondering what our Mexican maid would have served for lunch.

The blessed days his stock posted a bit higher, the old preening, confident James reappeared. On one of those mornings James looked up from the business section with his vulpine grin and said, “Let’s have breakfast.” He took the paper and me to one of the Sheraton’s palm-shaded beachside tables, where I devoured a cheese omelet and everything in the bread basket, just in case. James was scribbling on the stock quotes and I was licking the last delicious buttery crumbs off my fingers, when a good-looking man, American by haircut, demeanor, and madras shorts, walked up to the table and introduced himself.

He was the director of a commercial promoting Mexican tourism and the model they were supposed to be filming that day hadn’t shown up. The director asked me, “Would you like to be in the commercial? I can pay you a hundred dollars. All you have to do is run back and forth on the beach for an hour.”

James piped up, “Yes, she’d love to!” while I felt a sharp pang of regret about the four buttered rolls I had just eaten. I was wearing nothing but my cute bronze bikini, a shade darker than my skin, held together in strategic places by golden rings.

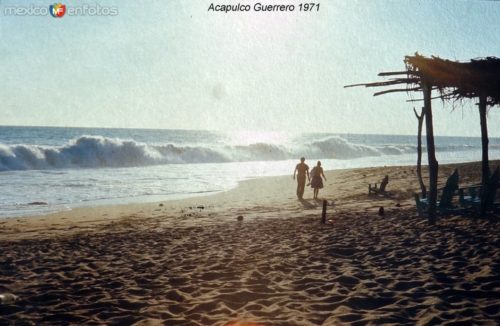

I followed the director down to where the waves frothed on the shore. It was the perfect Acapulco day, so gloriously sunny and balmy that it would inspire any snowbound Midwesterner to immediately start packing his bags.

The director pointed up and down the beach, in case I didn’t know where it was, said “Okay, start running,” and then yelled something at the cameraman. I ran, hopped, skipped, splashed, smiled, waved, and jumped around like an idiot, followed by the cameraman and the director, who kept yelling “Happier! Look happier!”

James stayed back at the Sheraton, stretched out on a lounge chair, admiring his handiwork each time I ran by. When it was over the director handed me a hundred dollar bill and promised to send me a copy of the commercial. At least I got the money. I saw the commercial once on TV, and only recognized it because my first thought was, “Hey, I have that same bikini.”

My sudden and accidental elevation into a professional model was a bigger boost to James’ ego then it was to mine. At the Villa Vera, he called me up from my swim-up bar stool to introduce me to yet another backgammon pigeon, saying, “This is my girlfriend, she’s a model.” James beamed as if he had sculpted me himself, a wolfish Pygmalion, and stroked my butt for good luck. Look, he was signaling his opponent, look at me, lucky and successful, a winner with a sexy young girlfriend. And now I’m going to beat the pants off you. Most of the time, he did. I was rewarded for my supporting role with thin gold chains for my wrist and neck, bijoux de plage, the sales lady said, simple and elegant. I still thought the uncut emeralds would look just fine on the beach.

For a few weeks, as his stocks kept ticking upwards, James gleefully slaughtered all comers at backgammon, and we were back in the Acapulco groove, as if no time or money had been lost, back to waterskiing in the morning, afternoons at Le Club (our entry into this private, posh oasis bought by James with a folded bill discretely palmed to the maitre d’), Carlos ’N Charlie’s for drinks and dinner if James was eating that evening, then always, always dancing at Armando’s.

It was the last good time.

One morning, James opened the New York Times to the stock pages and a black cloud covered his face and mood. This cloud did not blow away, but grew heavier and more ominous each day. There was nothing I could say, nothing I could do, except that hope tomorrow’s news would be better. It wasn’t, and neither was the next day’s. There was nothing James could do either, except watch his fortune evaporate. There was no more waterskiing, no more afternoons watching the peacocks strut around Le Club’s enormous pool. James got up in the morning, threw back his coffee, and headed straight for the Villa Vera. In their shadowy backgammon room James challenged his opponents to higher and higher stakes and became aggressively reckless with the doubling cue. It didn’t matter if he was winning or losing, I couldn’t bear to watch. I was grateful whenever James forgot to call for his lucky charm before facing a new opponent.

It didn’t seem possible, but meals became even more irregular. I looked in the mirror: I was model-skinny. James went from thin to cadaverous. Even though the sun shone every day, we carried our own bad weather with us. The fun, the glamour, were gone. We didn’t dance any more; James showed up nightly at Armando’s because that was what a happening guy in Acapulco did. He watched the happy couples on the dance floor and threw back vodka and sodas. I held my hands over my flip-flopping empty stomach and tried to figure out what would happen next.

It did not surprise me when James turned outlaw. There was always something felonious about him, a suspicion that there was a crime in his past or in his future.

Enough of winter had passed that it was safe for James to go back to Chicago without loss of face. He began planning our drive north, a plan that now included drug smuggling.

North Country Girl: Chapter 42 — The Trophy Girlfriend

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

Within a week James had shanghaied me out of the Canadian girls’ place and into his. I had left more roommates in the lurch, but at least I had already given them 30 dollars, my share of the month’s rent.

Was I in love with James? No, but I was enthralled. James scooped me up at a time when I was the most malleable, when I had wandered into this glittering new world and desperately needed a guide. I fell under James’ spell, bedeviled by his advanced age, his sophistication, his dark eyes, and his bottomless pockets, seduced by the red Jeep and James’ fancy beachfront condo, which he rented for the whole season.

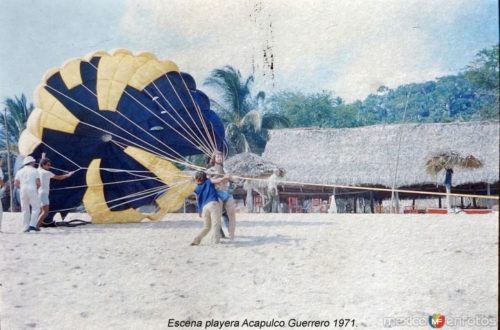

His eighth-floor apartment was sleekly modern, simply furnished, and huge. A dark curtained bedroom lurked in the back. In the living room, where we never sat, floor to ceiling windows on three sides looked out over the bay. Across the front of the apartment, facing the sea, stretched a wide, deep balcony with no neighboring buildings to interrupt the view. I loved to sunbathe nude out there, tanning my few remaining white bits. James watched me and I watched the parasailers, who occasionally soared by close enough for a look themselves. The parasail took off and landed right on the beach, towed by a small powerboat whose driver had a Corona in his hand at all times. Once I saw a guy coming in for a landing get slammed against the side of a hotel; more often, the poor tourists would get face planted on the sand and pinwheeled off their feet while the boat sped on, steered by a drunken captain who never looked back.

If I leaned way over the balcony railing, I could see the pool below, anemic blue and always totally empty, even though every lounge chair and umbrella table was occupied from morning till sunset. James refused to set foot in this pool. I realized years later during a trip to Florida that the residents in James’ building could have been swapped with those of any condo in Boca Raton. Even in glamorous Acapulco, that pool was where old guys drank and played cards while their wives boasted about the grandkids and complained about the help.

These retiree snowbirds living in his building acted on James like garlic on Dracula; every time we rode the elevator with one of them, James backed himself as far away as possible, doing everything short of throwing up his arms across his face in horror. James had an irrational fear of growing old; he wanted to look young, feel young, and hang out with people half his age. James didn’t have a wife who would call him away from his gin game because she couldn’t remember if little Aaron was eight or nine. He didn’t even play cards—that was for old men!—he preferred backgammon (which I had never seen before). James taught me my first Yiddish word: alte kaker, an old shitter. He did not want to hang around with the alte kakers, and forbade me from ever swimming in that pool. He acted as though old age were a contagious disease he was determined not to catch.

There was one alte kaker in the building who James could not avoid, as they were from the same town (although James always claimed he was from Chicago, he actually lived in Des Plaines), and James had once sold him a Cadillac. One day when I was sunbathing on the balcony, I heard the front door open and close and looked up to see James, accompanied by a pop-eyed Mr. Des Plaines, unfortunately wearing his usual Speedo, which was not quite covered up enough by his sagging gut. I grabbed a towel, James burst out laughing, and Mr. Des Plaines turned and ran out the door without a word.

I glared at James, who didn’t apologize but said, “Ever since I told him that you sit out here naked he’s been begging to come up. I hope he doesn’t have a heart attack. Now they’ll have something to talk about besides those damn grandkids.” I had yet to hear the word trophy used to describe a person, but that was what I was, clearly on display.

My time with James was an indulgent hedonistic dream, days that were not counted out by the teaspoons of Spring Break but seemed to stretch out forever. We spent the mornings water-skiing at the Pie de la Cuesta, a quiet lagoon north of Acapulco, that seemed another country away from throbbing discos and Arabian Nights beach clubs. Hammocks hung between palms, and fishermen grilled their catches over driftwood. There were no pushy beach vendors, no ragged kids selling Chiclets, and only a few tourists and Mexicans enjoying the calm, reportedly shark-free water. James loved giving me instruction in anything, from backgammon to tipping; under his tutelage I went from desperately hanging on to the triangle handle of the taut towrope, steeling myself for a head-first plunge off my skis and into the water, to being able to clumsily drop one ski and slalom, while still clinging to the rope like death. James, of course, was an elegant water-skier; he probably could have smoked a cigarette while effortlessly curving back and forth behind the boat.

In the afternoons we would head to Le Club or the Villa Vera. The Villa Vera, hidden away in the hills, was a once famous spot that had steadily been losing ground to the modern beachfront hotels. But it managed to hold on to its ’50s glamour, with small but luxurious villas and never-ending, high-stakes backgammon games. One of the main appeals of the Villa Vera for James was playing backgammon with two minor celebrities who had set up there for the winter. James preened as he introduced us; he got to show

off both his blonde 20-year-old girlfriend and his famous friends. Don Adams, Agent Smart from Get Smart!, was a complete jerk, always leering at me and anything else in a bikini, always rude to the staff, and always on the prowl for unaccompanied women who might be impressed by his minor stardom. James’ other backgammon opponent was the actor who played Superboy in the TV show The Adventures of Superboy, a claim to fame that he always had to repeat at least twice: “No, I wasn’t Superman…no, not the movie, no not Superman the TV show, it was a different show…” Of course I have forgotten his name. (But I looked it up! He was Johnny Rockwell, who went on to marry the heiress to the Mexico City Coca-Cola franchise.)

The Villa Vera also had a pool with that most brilliant of inventions, the swim up bar. I loved that bar, where I spent many hours with my butt perched on an underwater cement stool drinking bullshots while James took on all comers in backgammon.

A bullshot is vodka and beef consommé. It’s like a bloody Mary minus the tomatoes but with a lot more Worcestershire. I learned to drink bullshots at the Villa Vera because James did not believe in regular meals. He was as obsessed with getting fat as he was of getting old. He put off eating as long as possible, a whole day if he could. He had no problem having drinks from noon on though, without ever showing the least sign of drunkenness. A bullshot was as much a cup of soup as a cocktail, and for James, a couple of bullshots was a meal.

I, on the other hand, was always hungry.

At 20, I did not have enough confidence in myself to tell James I was going to order a club sandwich. I was so aware of the revulsion James felt for fat people that I constantly worried about my own weight. Minnesotans back then always carried a layer of extra fat, in case winter got so bad we had to go into hibernation. James worriedly pulled and prodded at his own taut stomach; if he believed he saw a centimeter of pudge he announced he was fasting that day. I surreptitiously pinched my own belly and compared myself to the endless array of perfect, bikini-clad bodies that constantly surrounded us.

When James, after several viewings of himself in the mirror, front, sides and back, did decide that it was safe for him to eat a meal, we always ate very well.

Sometimes James woke up hungry after a day of fasting, and we went to breakfast at the majestic Sheraton, one of the original Acapulco hotels and the only place where you could buy American papers (papers that had been published the day before). James studied the financial pages, lecturing me on PE ratios, margins, short sales, and many other topics, which unfortunately did not stick in my brain. I was too busy washing down my cheese omelet and bollitos (tiny fresh rolls, brown and toasty on the outside, fluffy and white on the inside, that begged to be smeared with butter and jam) with fresh squeezed orange juice and strong coffee that was constantly refilled by a waiter standing ready with a silver coffee pot and a small pitcher of warmed milk.

If James decided to break his fast at lunchtime, we went down to Paradise, a beachside restaurant, and had whole fried snapper and Coronas while we watched the parade of vendors haranguing the pale or sun burned tourists, tourists who then staggered off the beach over-burdened with silver jewelry, piñatas, marionettes, gaudily embroidered shirts, glittery sombreros, and ridiculously often, an entire onyx chess set.

Fortunately, even if James insisted that we skip breakfast and lunch, there was usually dinner, as like the rest of the beau monde of Acapulco, James had to make regular appearances at Carlos‘N Charlie’s, to see and be seen. Fito and I had perfected our ability to ignore each other, although Jorge smiled and waved as if he had forgiven me for everything; once he plaintively asked me if Mindy was coming back to Acapulco too.

James never took me back to the fancy spot with the towering arches; I guess that was a first date place. Instead we drove up into the hills to a funky little Mexican restaurant that had almost as good of a view, where every meal started with sangritas, a shot of tequila with a chaser of hot sauce cut with tomato and orange juices.

But my favorite place to eat was the bowling alley hidden away on a back street of rundown, downtown Acapulco, where we were the only non-Mexicans devouring blackened spit-roasted chicken and homemade tortillas. I don’t think I had ever before had a chicken that actually tasted like something; this was chicken-y chicken, juicy and smoky and crisp-skinned. We sat at one of the four oilcloth topped tables and tore the chicken apart with our hands, wrapped the meat in tortillas, and laced every other bite with a spoonful of spicy homemade pico de gallo.

Whether we had eaten breakfast, lunch or dinner, or none of the above, our days were well punctuated with cocktails and beers. And every single night you would find us at Armando’s, drinking and dancing and drinking. I don’t know how I wasn’t drunk all the time. James did not seem affected by alcohol. He liked Quaaludes, which he bought legally at a regular old farmacia, thanks to a prescription from his Mexican doctor. James also liked pot and coke but not in Mexico. He had seen a Mexican jail first hand, visiting a friend who had been arrested for marijuana. The Acapulco jail did not provide food for the inmates so James brought him ribs from Carlos‘N Charlie’s. From the way James described the jail, I would have been surprised if his friend had gotten to eat a single rib before being shanked for his meal, by a prisoner or a guard. After that experience James determined to never risk doing anything that had a chance of landing him in the Mexican casa grande. He stuck with vodka and ludes. Despite my fondness for most drugs, I could not see the appeal of Quaaludes nor could I handle them. After a few incidents of me falling asleep with my head on the table at Armando’s, James stopped offering me pills.

I would like to say that James and shared our life stories, but mine was barely 20 years of mostly wholesome living in Minnesota. That took about five minutes to cover. James was 42. He had been coming to Acapulco for years, staying from December till May (he was very vain about his year round tan). He was originally from Winnipeg (finally, we had something in common: we both came from small cold towns) but had moved to Chicago twenty-two years earlier escaping a shotgun wedding and the responsibilities of a family. (Wait, let me do the math.) He took as much pride in staying single as if he had escaped barehanded from a lion’s den.

James did not want to be the father of a 20-year-old girl, he wanted to go to bed with 20-year-olds. He had made such a successful getaway from Winnipeg and marriage that he had never heard from his abandoned daughter or her jilted mother. He had never even met his daughter. You would think that having a deadbeat dad myself that this tidbit would have curdled our relationship, but I was young and callow and about as introspective as a rock. He shrugged off his lost family, so I did too. Marriage, kids—who wanted those when there was disco and drugs, backgammon and beach?