The Birth of Washington, D.C.: 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the Nation’s Capital

President George Washington signed the Residence Act 230 years ago this week on July 16, 1790. The Act provided for the establishment of both a temporary and permanent seat of government for the young United States. The temporary seat moved from New York to Philadelphia, but the new and permanent seat would be built by the Potomac River. The site became Washington, D.C., and as famous as it is, there are still facts that many Americans may not realize about how it came together, and what it might yet be. Here are ten things you didn’t know about the nation’s capital.

1. It’s in the Constitution

Article I of the United States Constitution immediately concerns itself with the establishment of the legislative branch and the creation of the House and Senate. In Section 8 of Article I, the powers of Congress receive some fleshing out (like the laying and collection of taxes, war declaration powers, post office creation, etc.). Clause 17 of that section also gives Congress the ability to create a federal district for the nation’s capital with the phrase “To exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of Government of the United States.”

2. Maryland and Virginia Donated the Land

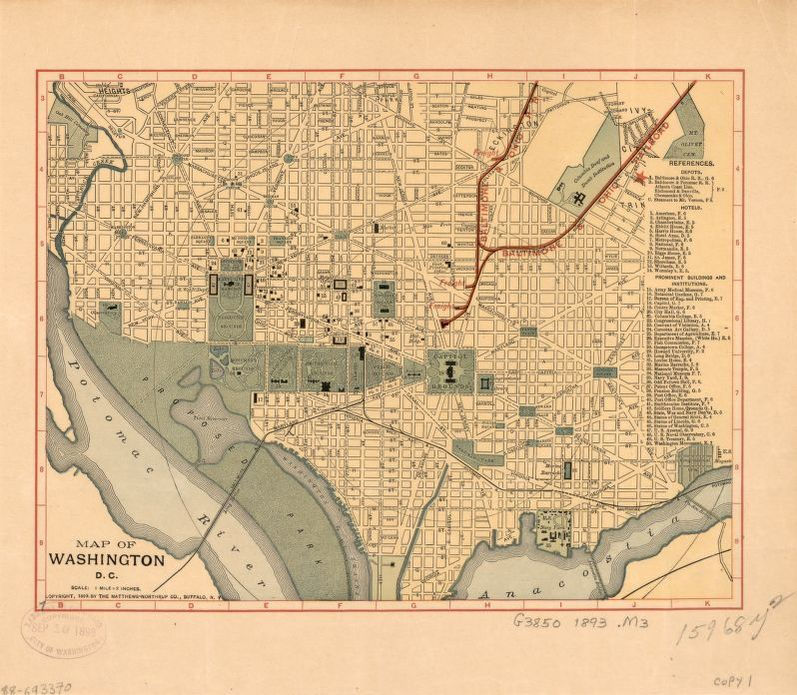

The language in the Clause that indicates “by Cession of particular states” meant that pre-existing states would donate the land for the new federal district. Maryland and Virginia donated the land that comprised the 10×10 mile square, which was also stated in the Constitution.

3. The Residence Act of 1790 Made It Official

Signed 230 years ago this week by President George Washington, the Act fixed the future seat of government at the Potomac site. A deadline of December 1800 was established for the new capital to be in use. The Residence Act also gave Washington the authority to appoint commissioners to run the project.

4. Why It’s the District of Columbia

Surveying and construction was soon underway. The appointed commissioners chose a name for the new federal city and district on September 9, 1791. The city itself was named after the first president (who had, after all, signed the Residence Act into law). The federal district was named the District of Columbia for reasons that run from obscure to uncomfortable now. For quite some time, “Columbia” was a nickname for America as a feminine form of Columbus (which is, of course, a controversial topicThe song “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” was even a contender for the official National Anthem. So, the city is called Washington, D.C. with the city and district in the same way that you would identify a city in a state as, for example, Indianapolis, Indiana.

5. The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801 Covered the Details

Congress finalized the fine points with the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801. An organic act determines the necessary pieces of how a territory is defined, including what body has authority over it. Being a federal district, Washington, D.C. is overseen by Congress. The Act also created two counties within the district, Alexandria County (south and west) and Washington County (north and east), each with a court. As the district encompassed the pre-existing cities of Alexandria and Georgetown, they hewed to their already established local laws. However, as the district, including those cities, fell under federal control, Congressional representation was removed since the cities were no longer part of the states that they were originally in. The fact that D.C. residents pay taxes without representation has long been a bone of contention and is one of the primary drivers behind the “D.C. Statehood” movement.

6. John Adams Was the First President to Live There

John Adams was the second president, serving from 1797 to 1801, but he was the first to live in the White House in Washington, D.C. Adams and his wife, Abigail, moved into the House in 1800 before it was even completed. In the widely acclaimed HBO mini-series John Adams, which won 13 Emmys and four Golden Globes, the arrival of John and Abigail at the White House was dramatized. The scene makes a point of the irony that enslaved people built the “free” nation’s capital; while John and Abigail Adams were not slave owners themselves, they occasionally paid slaves owned by other district residents to do work at the property. The scene is reportedly accurate in its depiction of the conditions around the White House; while the building proper was finished, the surrounding area was largely muddy and uncleared upon their moving in.

7. The War of 1812 Wrecked the Place

The War of 1812 ran from June of that year until 1815, pitting the young United States against Great Britain. In 1814 on August 24, British troops made it to Washington and set about burning the city. The Capitol building suffered tremendous damage, including the loss of the then-current 3,000 volumes of the Library of Congress. The White House burned, as did the U.S Treasury, the Department of War, and other buildings. Fortunately for what was left, an enormous storm broke loose over the city and the pounding rain put out many of the fires. The storm touched off at least one tornado in the city, and the British withdrew to their ships, which were taking damage from the storm. All told, the British occupation of D.C. lasted just over a day, but much of the city, particularly the government buildings, would have to be completely rebuilt in the aftermath.

8. D.C. Had Famously Bad Water

A Killer in the White House. (Uploaded to YouTube by The Saturday Evening Post)

As documented in a Post story from 2019, early D.C. had no sewer system. The White House itself would have no running water for years; water was still being carried in by buckets before the fire in 1814. The Jefferson administration had looked into pumping in water as early as 1807, but no running water came until 1833. Unfortunately, there would be several problems with that over time, as the video above documents.

9. The Smithsonian Institution Started with a British Donor

Washington, D.C. is also home to The Smithsonian Institution, which was founded in 1846 and continues to be administered by the U.S. government. The name comes from James Smithson, a British scientist who made the original donation for a national museum. The Smithsonian as a whole includes 19 museums and galleries, most of which have enormous digital collections and videos that you can see at their sites online.

10. They’re Still Building Monuments

One could be forgiven for thinking that monument-building in D.C. has come to an end, but the city continues to add monuments and memorials to important people and events. The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial is still scheduled to open in September of 2020. Among the projects currently in the works is a National World I War Memorial that will be located in Pershing Park and memorials to Gulf War/Desert Shield/Desert Storm veterans, Native American veterans, and both free and enslaved Black Americans that served in the Revolutionary War. The Korean War Veterans Memorial is also slated for a “wall of names” like the one already featured at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Out of the Dark

Virginia Jacko was going blind. She knew it, but not everyone else did. Since the mid-1990s, her vision had been steadily deteriorating. Though capable of seeing people and objects in front of her, she might not recognize a person standing at her side. Finally, in 1998, then in her 50s, Virginia was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, an irreversible disease affecting about 1 in 4,000 people in the United States. The disease attacks the cells controlling night vision and peripheral vision first. But in advanced cases, such as Virginia’s, it robs central vision, eventually leading to blindness.

So it was with trepidation that Virginia arrived at the office of the incoming president of Purdue University for an initial meeting with her new boss. She wanted to assure the president that she could still fulfill her responsibilities as the financial advisor to the president and provost.

For years now, she’d found ways to adapt her personal and professional life to an increasingly narrow visual world. She scouted out meeting sites ahead of time. She’d stopped driving, relying on taxicabs if she needed to get somewhere quickly. She prepared for meetings at night, her face close to the monitor so she could read words on the screen and memorize data on Excel spreadsheets. “I never got depressed or felt sorry for myself,” says Virginia. “Negative energy is just a waste of time.”

But that fateful morning in late 2000, as she reached the office of the president’s assistant, her heart sunk. The president had ordered new furniture that completely changed the layout of the room. Virginia realized she would not be able to navigate the space without help. So, thinking fast, she pretended to be running late for the meeting and waited for the president to step away from his office. When he did, she slipped in, guided by the assistant, and sat down on the couch. When he returned, she merely had to stand up to greet him.

The plan was a success, but the experience was a loud wake-up call that Virginia couldn’t ignore. She needed to learn to live as a blind person if she was going to succeed in a sighted person’s world. Her vision was getting to be too much of a problem to conceal. After the meeting, she called her husband Bob, a professor of civil engineering at the same university. She told him she needed to take a three-month medical leave. She would study at a vision rehabilitation facility.

One of her three children, Julie, urged her to check out the Miami Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Virginia and Bob owned a condominium in Miami, so she would have a place to stay. Once there, Virginia immersed herself in the world of the blind, honing skills she once took for granted, such as baking oatmeal cookies and sewing buttons on clothes. She soaked up everything she could learn about computer programs for the blind, including programs that convert text to speech. After the three-month program, Virginia felt a renewed sense of confidence. “I learned that a blind person can do anything a sighted person does. They just have to learn to do things differently,” she says.

At the end of her medical leave, Virginia was at a crossroads. She could return to her job at Purdue and continue to advise the president and provost on financial affairs. Or she could continue her efforts to regain her mobility by enrolling in a one-month, 24/7 intensive training program with a guide dog. She chose the latter.

By then, not only was Virginia completely blind but for the first time in her life, she was stepping into the future without a clear career path. Yet she was at peace with her decision. “I had changed. Walking out the doors of Miami Lighthouse as a graduate of the program, I realized that my passion was helping the blind,” she says.

Virginia’s husband Bob spent three months with her in Miami while she completed the program but, as a tenured professor, he had to return to Purdue for the new school year. Virginia would stay in Miami with her new guide dog Tracker, immersing herself in work at the Miami Lighthouse. She began as a volunteer, but such was her financial experience—and drive—that she soon became treasurer and a member of the board.

Not everything went smoothly for Virginia as she adapted to her new life. Once, while out on a stroll along a coastal walkway, Tracker stepped aside to avoid colliding with a woman pushing a stroller. The sudden move knocked Virginia off the breaker wall and she plummeted into the sea. Virginia calmly treaded water until someone lowered a ladder, allowing her to climb back up to solid ground.

Another time, she attempted to sit down for lunch at a restaurant in a major department store, only to be told she couldn’t bring Tracker into the restaurant. Not one to be easily thwarted, she stood her ground and seated herself with her guide dog at a table. That day, she called the company’s headquarters and advised that the incident would result in a public relations fiasco unless changes were made. In no time, the chain changed its policy, and it now provides Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliance training for all employees.

In early 2005, the president and CEO of Miami Lighthouse left unexpectedly for personal reasons. The chairman asked Virginia to serve as president and CEO on an interim basis until a permanent replacement could be found. Following a nationwide search, the board selected Virginia, making her the first blind president and CEO in Miami Lighthouse’s 81-year history.

Virginia wasted no time in growing the organization by offering innovative programming as she deepened relationships within the philanthropic community. “When I took over in 2005, we had one grant and today we have more than 30 active grant awards,” she says.

Thanks to her outreach efforts, revenue has nearly tripled, allowing the organization to vastly increase the scope of its services. Today, Miami Lighthouse teaches rehabilitation skills to people of all ages—from blind babies to seniors with low vision—allowing them greater mobility and self-reliance. Miami Lighthouse has become a center of excellence in vision rehabilitation because of its innovative programs, such as sound engineering and mobile eye care for low-income schoolchildren. All told, under Virginia’s leadership, the organization has increased the number of people it serves fourteen-fold to about 10,000 annually.

All of this on a budget that Virginia watches like a hawk. For five consecutive years, Miami Lighthouse has received the highest rating from Charity Navigator, America’s largest independent charity evaluator of financial health and accountability.

Virginia’s disability has never slowed her down. “Virginia is such a determined person. Having a deep faith; supportive family; and positive, can-do attitude are at the core of her success,” says Doug Eadie, co-author of Virginia’s autobiography, The Blind Visionary.

“I am so blessed,” Virginia says today. Her blindness, she feels, was a gift that allowed her to find a new mission and purpose in life. “We transform people’s lives at Miami Lighthouse every day. I lost my vision, and I found my passion.”