Destino: When Disney Met Dalí

Imagine unearthing a Picasso in the corner of your basement, perfectly preserved for decades before you finally uncover it. Roy E. Disney experienced this in 1999 when he stumbled across Destino, the 1946 collaboration between his uncle Walt Disney, the animation pioneer, and Salvador Dalí, Spain’s legendary surrealist painter. And his decision to revive the project left us one of the most interesting collaborations in animated film history.

How many stars had to align before Disney’s creativity and Dalí’s imagination finally came together? It turns out, all they really needed was a dinner party hosted by Jack Warner (of Warner Bros. Studios). Walt Disney had caught the surrealism “bug” while creating Fantasia, and with it came the desire to continue dabbling in projects that carried the same dreamy element. Similarly, Dalí had a newfound fascination with cinematography and was determined to become the first popular surrealist to invade the film industry.

The story of their initial meeting has been passed around like folklore. It could only be verified through John Hench’s recollections and Jack Warner’s guest list. As the legend goes, at Warner’s party, Dalí and Disney immediately connected, and an overjoyed Dalí accepted Disney’s proposal to collaborate on a surrealist animated short. Over the next eight months, they created more than 200 storyboard sketches set to a love ballad composed by Fantasia composer Armando Dominguez. Their paired ambition (along with John Hench’s tremendous draftsmanship) resulted in the story of a haunting romance between two star-crossed lovers: Dahlia, a mortal woman struggling to find love, and Chronos, an all-powerful titan and the personification of time itself.

Sadly, financial struggles after World War II forced the studio to place the project on an indefinite hiatus. Destino spent the next five decades hidden in the Disney archives.

Destino was a project shared between two great artists at the peak of their powers. Dalí and Disney strove to bring people out of their daily tedium into what they considered better, more imaginative worlds. In their six-and-a-half-minute film, objects around Dahlia break or melt away as she dances her way through the scenery. She moves in and out of landscapes like a trapeze artist while her large, longing eyes scan the terrain for her lover. Her body undergoes drastic transformations — taking the shape of a bell tower, a dandelion, a ballerina, and a baseball — all in hopes of finding a form that can coincide with Chronos’s immortality. In turn, Chronos tries to meet her efforts by breaking free from his bonds.

But large towers prevent them from reaching each other. It takes a variety of surreal movements and shifting scenery before Dahlia’s bell tower appears in the hole in Chronos’s heart, signifying that the two have finally become one.

It took nearly 60 years for Destino to finally be completed — 37 years after Walt Disney’s death and 13 years after Dalí’s. By the time the artwork was rediscovered, nearly 50 original sketches had been lost or damaged due to poor preservation. Roy Disney re-recruited John Hench to help revive the project in 2002, and together, they stitched the remaining sketches into a single piece, keeping as close to the original storyboard as they could. Fans of Disney and Dalí will find that both artists’ styles are clearly evident throughout the film.

The final product was released on June 2, 2003, at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival. It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film and honored in multiple exhibitions. It won titles in the Chicago, Rhode Island, and Melbourne International Film Festivals and even inspired its own four-star resort in Talamanca, Spain.

Disney and Dalí got more than what they bargained for out of their partnership. The Destino collaboration led to a lifelong friendship between the man behind the mouse and the painter of melted clocks. It’s more than just a surrealist 1946 package film. It’s a melding of the styles of two of the 20th century’s most imaginative minds.

Pinocchio Dies, Bambi Gets Shot, and Other Surprising Changes to Disney Movies

Every piece of art starts somewhere. Inspiration can be easily found in original thought, personal experiences, or in older works. It’s not a surprise that a large percentage of films (more than 55% as recently as 2015) began as books and fewer still began as poems. When you have a studio with as long and varied a history as Disney, you’re bound to discover that ideas occasionally come from very unlikely places and with some startling plot developments. With this week’s release of Christopher Robin, itself a new twist on an old series based on books, we look at a few of the more surprising story changes that it took to get some of your favorite Disney films on the screen.

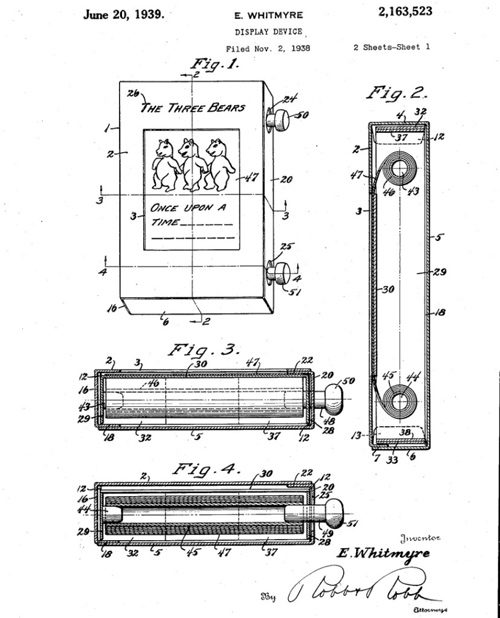

Dumbo Started as a Toy and Book Concept

Dumbo began life as toy and book combo, a prototype called a Roll-A-Book where one would scroll up and down to read the pages. The story was by Helen Aberson with art by Harold Pearl. The marketing department brought the piece to Walt Disney; he skipped the device and went right to the story, buying the rights. Disney’s story department made some changes, including switching out Dumbo’s bird companion for Timothy Mouse. The movie also grew as it went; originally intended to be a short, it expanded as Disney realized its potential. He wasn’t wrong; released in 1940, Dumbo turned out to be the studio’s biggest box office hit of that decade.

Bambi Gets Shot

Two years after Dumbo, Disney released their adaptation of Felix Salten’s novel, Bambi: A Life in the Woods. The Austrian novel published in 1923 and was widely praised, especially for the current of environmentalism that runs through it. The book also has a larger cast of deer and some heavier themes. While Bambi’s mother meets her familiar fate, Novel Bambi also has a cousin named Gobo that dies. In a way, his death is even more tragic, as he was captured and raised by people for a time, only to die when he approaches a hunter under the misconception that humans were now safe. Bambi himself takes a bullet at one point, but survives after being rescued by his father, the Old Prince. On a different note, the book was banned in Nazi Germany under the belief that the relationship between man and deer was an allegory for the treatment of Jews (Salten was Jewish). Max Schuster of Simon & Schuster published the book in the United States and later helped Salten escape Germany; furthermore, he introduced the author to Disney, facilitating the adaptation.

Pinocchio Died by Hanging

Carlo Collodi wrote The Adventures of Pinocchio in Italy in serial form in 1881 and 1882, then published the collection as a book in 1883. Pinocchio was a real jerk. He starts kicking Geppetto before the old man is even done carving him. Soon after, a talking cricket tries to warn Pinocchio about bad behavior, but the animated puppet kills it with a hammer (to be fair, that was an accident). The wooden miscreant goes on to commit several other misdeeds before the Cat and the Fox hang him at the end of the fifteenth chapter. Collodi’s editor talked him into changing the ending, and the writer would compose 20 further chapters, including the puppet’s resurrection by the Fairy with Turquoise Hair, and his eventual transformation into a real boy. When Disney picked up the rights, a wide variety of changes were made to soften the tale. Nevertheless, The Adventures of Pinocchio, bad behavior and all, remains the most translated Italian novel.

101 Dalmatians Met Aliens

Dodie Smith’s 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians (or The Great Dog Robbery) would seem fairly familiar in most respects. You have Cruella de Vil, you have the same basic plot, and you have other animals, including a sheepdog, involved in the rescue. The biggest divergence is that there are four adult dogs; Pongo and Missis are the parents of the first 15 stolen puppies, and Prince and Perdita are the parents of a number of other missing puppies. For simplicity’s sake, the film script composited the two dog couples and changed human owner Roger from an accountant to a songwriter. That’s all basic adaptation stuff. What makes the origin here so notable is the reason that Disney never adapted the sequel; frankly, it’s weird. Named The Starlight Barking, the novel deals with humanity being placed under slumber by Sirius, Lord of the Dog Star, an alien canine that has come to warn the animal population that they need to escape Earth before nuclear war begins. We are not kidding. Put into the role of spokesdog, Pongo decides that the dogs should remain with their humans on Earth. Having typed that, we kind of want to see that now.

Hey, Why Don’t We Start with the Second Book?

1985’s The Black Cauldron is frequently considered a low point for the animation studio. Intensely disliked by fans of the source novels and a box office loser for the studio, it generally gets praise only for the score by Elmer Bernstein and its early successful use of computer-generated graphics in some scenes. Part of the story problem hinges on the fact that the film is the adaptation of the second book in a much-loved series, The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander. By all accounts, development was a mess from acquisition of the film rights on up until release, with numerous directors, designers, and animators entering and exiting the project, characters being constantly redesigned, and whole chunks of story being excised. One of the animators who had his designs tossed out was Tim Burton. What remains is a blending of the plot of the first two novels in the series with many important characters and villains omitted, while the characters that remained were largely rendered as more child-like and, well, goofy. The Horned King, an amalgam of two novel villains, stands out as a great design, as do the zombie-like Cauldron-born, but the clashing tones just make it more susceptible to criticism.

Fantasia Got Bigger Than Goethe

Fantasia is now regarded as one of Disney’s finest achievements. In the ’40s, it was considered a box office flop. That’s ironic considered it came into being as an attempt to save a budget. Previously, the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment was intended to be a short, an adaptation of the poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the author of Faust. As work commenced, the budget kept getting bigger, despite conductor Leopold Stokowski volunteering to work for nothing, owing to his enthusiasm for the project. As costs ballooned, Walt Disney envisioned animating a whole concert, rather than one piece, and marketing it as an experimental venture marrying the best of classical music with the best of animation. And while the initial release struggled to make money in 1941, in part due to World War II cutting off distribution in Europe, the film’s reputation has grown and the budget earned back many times over from re-releases, soundtrack sales, and the ongoing marketing of merchandise based on Mickey’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice appearance.

Lady, Meet Tramp

Joe Grant, one of Disney’s story developers, originally suggested a story based on his own Springer Spaniel named Lady; Lady, it seems, acted jealous around the new baby at home. Walt liked the idea in general, but not the original treatments for it. In 1945, Walt read a story in Cosmopolitan called “Happy Dan the Cynical Dog” and realized that Ward Greene’s story of a wisecracking mutt could work with Grant’s Lady. Walt bought the “Happy” rights from Greene. The combined story would go through a number of revisions over the years; in fact, Grant left Disney in 1949, six years before the movie would be released. In a clever tie-in, Disney hired Greene to write the novelization of the film.

Big Hero 6 Comes from the X-Men Universe

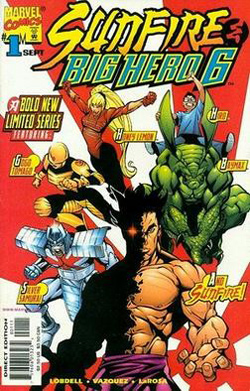

Disney’s Big Hero 6 opened to critical acclaim and huge box office in 2014, earning over $650 million worldwide and capturing the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. What a lot of people don’t know is that Big Hero 6 is an obscure Marvel super-hero team created by the Man of Action writer collective that got their start in an issue of Alpha Flight. Alpha Flight is Marvel’s team of Canadian super-heroes, originally introduced in X-Men #120 in 1979. In a 1998 issue of Alpha Flight, the characters team up with a group of Japanese heroes to stop a threat in Japan. In addition to new characters GoGo Tomago, Honey Lemon, Baymax, and Hiro Takachiho, the roster includes former X-Men member Sunfire and his cousin, the sometime-hero/sometime-X-Men-antagonist Silver Samurai. They soon spun off into their own mini-series as well as team-ups with other heroes, like Spider-Man. After Disney acquired Marvel in 2009, they began to actively develop a number of properties, including Big Hero 6. With Sunfire and Silver Samurai falling under Fox’s license to use the X-Men characters, the Disney film would opt to use two other Big Hero 6 allies/members from the comics in their place: Wasabi No Ginger and Fred (aka Fredzilla). The rest is animation and Oscar history.

The Art of the Post: Gustaf Tenggren: The Man Who Shaped Disney’s First Animated Movies

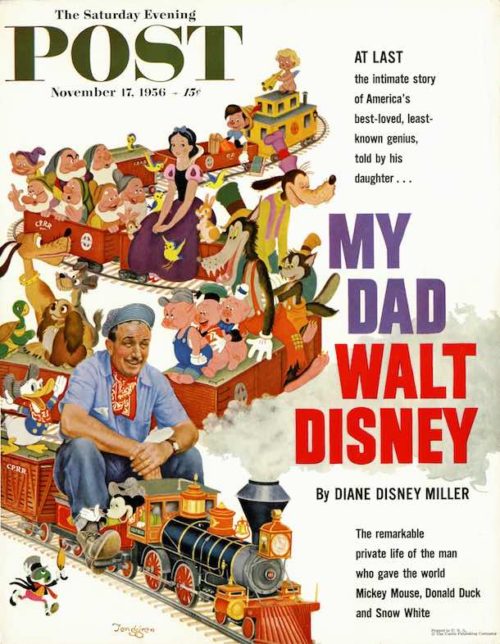

When the Saturday Evening Post ran a cover story about Walt Disney in 1955, it needed to find a cover artist with two very different talents: one “who could accurately depict Disney’s famous [cartoon] creations and one who could handle the quite different job of portraying the cartoonist himself.” ¹ None of the Post’s regular cover artists would do. Art editor Ken Stuart launched a nationwide search for the artist he knew could do the job: Gustaf Tenggren. Eventually, he located Tenggren on a remote farm in Maine and persuaded him to paint this cover:

But what made Gustaf Tenggren uniquely qualified to illustrate this particular cover?

Like his cover, Tenggren combined qualities from very different worlds. Born in 1896, he grew up on a remote farm near Västergötland, Sweden. His father abandoned the family, leaving the boy to spend an impoverished childhood with his grandfather under primitive conditions and with few childhood friends. Yet by age 25, he was a successful illustrator in Manhattan. He then moved to Hollywood, where, combining the worlds of art and science, he played a key role in the birth of feature animated films for the fledgling Walt Disney Company. He was also the illustrator of the top-selling children’s book of all time, The Poky Little Puppy.

Tenggren eventually left the Disney studio because of artistic differences with Walt Disney. He lived in many places before settling down to live his final days on a farm in Dogfish Head, Maine, because it reminded him of the Swedish countryside. And that’s where the Post found him.

On June 22, 2017, Tenggren, who died in 1970, was inducted into the Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame.

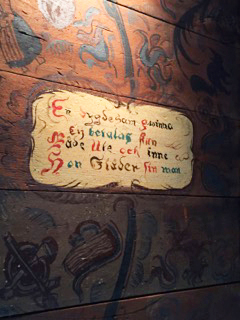

Tenggren’s life is a good example of how artists can make creative use of varied experiences. As a young boy, he tagged along with his grandfather, who went door to door painting traditional Swedish designs in the homes of villagers. He recalled, “[M]y grandfather … was a woodcarver and painter, and also a fine companion for a small boy. I never tired of watching him carve or mix the colors he used when commissioned to decorate, with typical primitive designs, churches and public buildings in the community.”²

Tenggren couldn’t afford art school, so the local community arranged for an art scholarship, which changed his life. In 1920, Tenggren left Sweden with his new wife and headed for the United States, where work was plentiful. He settled in Cleveland and within six months was painting a cover for Life magazine (the April 1921 issue). He recalled, “Those were busy days, drawing for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, painting six posters weekly for Keith’s Palace Theater, fashion drawings for a department store, and at the same time working full time for an art studio.”³

Within two years, Tenggren moved to New York City. The boy who grew up on an isolated, rocky farm in Sweden loved the big city: “For many years my studio was in this great city. Work was plentiful and during this period I illustrated a number of children’s books.” Tenggren became a well-known book illustrator, working on classics like Mother Goose, Hans Christian Andersen, and Heidi. He illustrated at least 22 books between 1923 and 1939. He also illustrated fiction and advertisements for magazines. In 1934, Tenggren encountered a talent scout for Walt Disney, who was searching for artists to work on the world’s first full-length animated feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Tenggren jumped at the chance and moved out to California in the early spring of 1936 to start work as an art director on Snow White.

Famed Disney animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston witnessed Tenggren’s great contribution at the formative stage of the creative process. They wrote:

Before any actual story work was begun, Walt would look for an artist of unique ability to make some drawings or paintings that would excite everybody. … He brought in top illustrators of children’s books, such as … Gustaf Tenggren to explore the visual possibilities of a subject. … These inspirational sketches started the whole staff thinking.

Tenggren drew upon his childhood experiences with his grandfather for some of the most dramatic scenes, including the rustic cottage of the seven dwarfs, the deep woods where Snow White flees from the hunter and the evil queen’s laboratory where she concocts the poison apple.

Filmgoers today may forget the significance of Snow White, but film critic and historian Roger Ebert wrote, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was immediately hailed as a masterpiece. (The Russian director Sergei Eisenstein called it the greatest movie ever made.) It remains the jewel in Disney’s crown.” Technologically, Disney’s rich, colorful films were a great leap forward in expressive imagery.

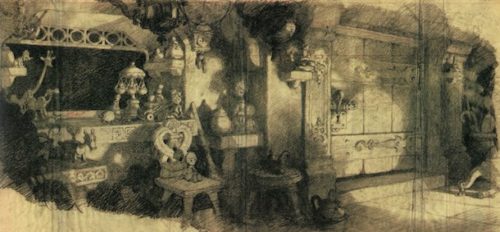

Tenggren’s success with Snow White earned him an even greater role in Disney’s next feature film, Pinocchio. Biographer Lars Emanuelsson described Tenggren’s contribution:

The look of Pinocchio, on which he was engaged during the major part of 1938, owes much to Tenggren’s creative input. The interiors and exteriors, the Tyrolean clothing, the craftsman’s workshop, the painted dolls and toys and the decorated and carved wood work were all heavily influenced by the conceptual drawings Tenggren worked on while the film was in production.

Tenggren’s beautiful watercolors of the small towns with carved wooden beams and furniture, Geppetto’s workshop with its cleverly painted surfaces, and the underwater scenes remain some of the highlights of Disney’s art.

Tenggren also worked on the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” section of Fantasia and on shorter cartoons, such as The Ugly Duckling, The Old Mill, and Hiawatha. Shortly after Disney started work on Bambi, he and Tenggren parted company.

In 1940, Tenggren produced his first children’s book bearing his own name, The Tenggren Mother Goose. This was followed by books such as the Tenggren Tell-It-Again Book, Tenggren’s Storybook, Tenggren’s Farm Stories, Tenggren’s Folk Tales, and Tenggren’s Pirates, Ships and Sailors. These books were highly popular. Tenggren and his wife were able to spend time traveling in search of a home where they could finally put down roots. They tried Mexico, Florida, and Cape Cod before deciding upon a farm in Maine, which they furnished with Swedish antiques.

Among his most important and best received projects during this period were Tenggren’s Golden Tales from the Arabian Nights which employed rich decorative middle eastern patterns in vivid images and The Canterbury Tales, which updated Chaucer’s classic for children. But he was best known to the general public for his series of Little Golden Books. He illustrated 28 books in this series between 1942 and 1962, including the classics The Poky Little Puppy, The Saggy Baggy Elephant, The Shy Little Kitten, The Big Brown Bear, and The Little Trapper. The prolific Tenggren continued to work from his home in Maine until his death from lung cancer on April 6, 1970.

Tenggren’s induction into the Illustration Hall of Fame confirms his key role at the dawn of animation and the importance of his many illustrated children’s books. His imaginative creations will long be remembered and enjoyed by audiences around the world.

1 source: Saturday Evening Post brochure Take Five, vol. 1, no. 7

2 They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Golden Age by Didier Ghez

3 They Drew as They Pleased: The Hidden Art of Disney’s Golden Age by Didier Ghez