The Art of the Post: The Mystery of Walter Hunt Everett

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

One of the most promising young illustrators ever to work for The Saturday Evening Post was Walter Hunt Everett.

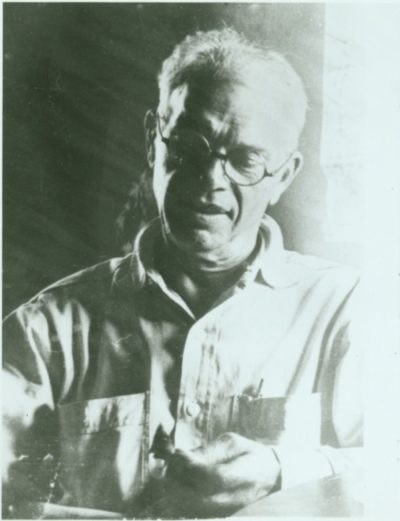

At a very young age, Everett was recognized as immensely gifted, a potential successor to Howard Pyle, the father of American illustration. Some thought his talent rivaled the young Norman Rockwell. But halfway through his career, at the height of his powers, Everett mysteriously dropped from sight. He quietly passed away in 1946, largely forgotten.

In 2014, the Society of Illustrators resurrected Everett’s reputation and elected him to their Hall of Fame based on the first half of a promising career. Illustration expert Kev Ferrara, writing for the Society, enthused: “based on the evidence he left behind, the man was a genius.” Ferrara noted that Everett was “deservedly revered during the Golden age of American illustration,” and concluded that his few remaining paintings showed Everett was “among the most daring and inventive of the great illustrators.”

So what happened?

Everett’s childhood revolved around his drawing and painting. He rode a bicycle 30 miles to take art lessons from Pyle, who immediately recognized Everett’s potential. When he graduated from Pyle’s school, Everett drew this elaborate sign as his notice to the world that the young illustrator was open for business:

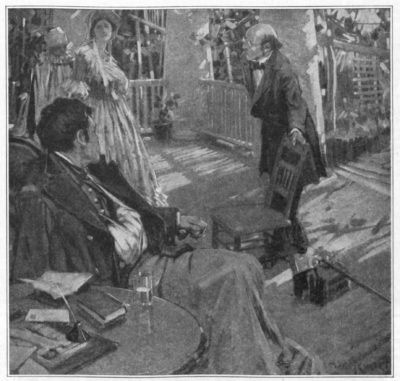

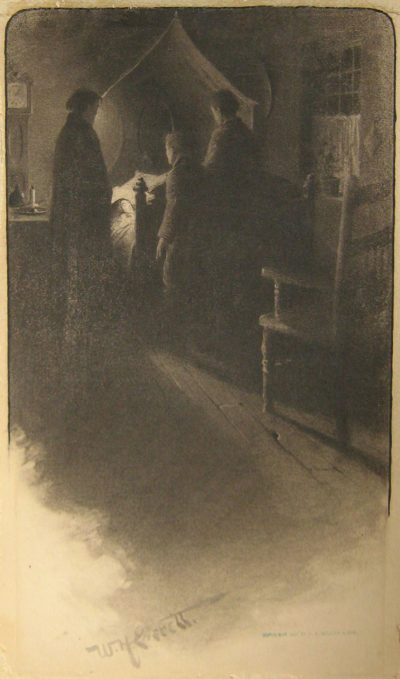

Everett quickly found work for some of the most prestigious illustration markets in the country. For example, at age 20 he drew this beautifully composed picture for Colliers:

Note how Everett put his bold and prideful signature right up front:

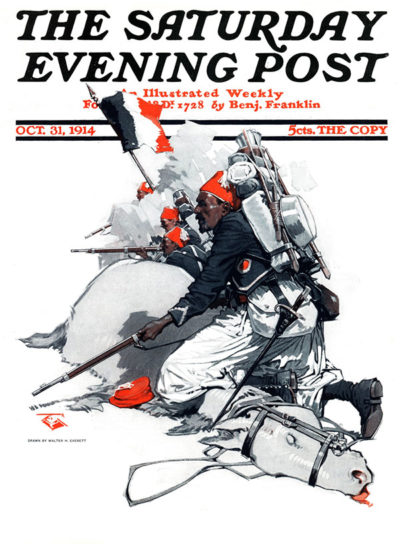

By age 30, Everett was a regular artist for The Saturday Evening Post. He painted his first cover in 1910 and served as a regular contributor from 1910 to 1917. Unlike famous Post illustrators such as Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker, Everett did not paint in a consistent, realistic style. He experimented with vignettes and later with flat patterns and compositions created by light.

©SEPS

Everett was such a perfectionist that he sometimes ignored his deadlines in order to get things right. He spent countless hours mastering his craft, working with paintings, and trimming and reshaping his beloved brushes. He even designed his own easel (which he imported from France). In 1917, he stopped working for the Post’s deadlines to work more intensely on the art that interested him. Around the same time his neglected wife and son finally lost patience with his art obsessions and left him.

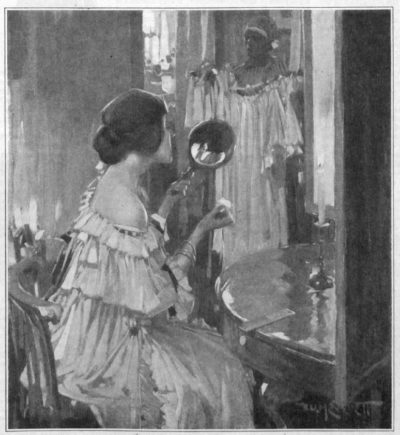

Reaching maturity, Everett turned out paintings that were a cross between illustration and fine art:

This painting is a masterpiece of color and light, but Everett worked on it so long that his client didn’t have time to print it in color, so they had to settle for black and white.

Then, in the 1930s at the peak of his career, in what must have been by an act of howling madness, Everett “gathered the bulk of his life’s work,” burned it to ash and disappeared from illustration forever. His family reported that he moved to the small, quiet town of Parker Ford, Pennsylvania where he seems to have spent his remaining years chipping away at stones to make arrowheads. He purportedly made thousands of them.

His family recalled that by this time “he could not care for himself.” There was speculation that he suffered from depression or some other mental disability. His ex-wife returned to his side and nursed him until he finally passed away from emphysema.

Instead of a rich legacy of hundreds of paintings left behind by other Post illustrators such as Rockwell and Leyendecker, Everett left behind a cardboard box full of arrowheads.

Featured image: Cover from October 15, 1904 (©SEPS)