100 Years Ago: A President Silences His Critics

Earlier this month, President Trump, angered over critical reporting by journalists, pondered via Twitter whether he should revoke their press credentials. This bitter feud between press and president has raised an old question: Does the president have the right to silence people who criticize him or his policies?

Congress debated that question 100 years ago and believed so strongly in such executive privilege that it passed the Espionage and Sedition Acts to stifle dissent in America.

President Woodrow Wilson expected criticism after he asked Congress to declare war on Germany, sending America into World War I. He had, after all, been elected on his record of keeping the U.S. out of the war. Now he’d committed the country to that contest, and he knew he’d need strong public support for the war effort. He would tolerate no criticism that might discourage military enlistment, the sale of war bonds, or cooperation with rationing programs. He needed loyal Americans — loyal, that is, to his plans.

But there were strong anti-war feelings among pacifists, socialists, and union organizers, as well as immigrants. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were eight million first- and second-generation Germans living in the U.S. Many retained a strong attachment to the land of their birth. Wilson believed they might dampen the war effort with pro-German sentiments, and he feared German agents hid among them, embedded at all levels of American society. German saboteurs had already destroyed a major munitions depot in New York Harbor.

Wilson proposed a bill to silence criticism of the war. The result was the Espionage Act, which became law on June 15, 1917, and prohibited anyone from aiding America’s enemies in wartime or interfering with the armed forces and its recruitment efforts. It also made it illegal to make false statements that disrupted military operations, promoted the enemy’s success, or led to insubordination or disloyalty.

But the Espionage Act didn’t end the dissent. A Montana rancher publicly called President Wilson “a Wall Street tool” and said he’d leave the country rather than go to war. He was tried under the Espionage Act but acquitted on appeal because he didn’t directly affect war efforts. In response, the U.S. attorney general called for a law to broaden the Act’s powers.

So Congress extended government control to affect speech and writing. The Sedition Act of 1918 made it a crime to use “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language” about America’s government, its flag, or its armed forces. Making any statement that inspired contempt in others for the government or its institutions was also outlawed.

Theodore Roosevelt protested the law, saying it was “a proposal to make Americans subjects instead of citizens.”

But some legislators thought it didn’t go far enough to root out dissident thinking. A New Mexico congressman was disappointed the Act didn’t provide the death penalty. And an unsigned editorial in The Washington Post stated, “Enemy propaganda must be stopped, even if a few lynchings may occur.”

The Saturday Evening Post editors supported the Act. The government didn’t need a sedition law to protect itself, they said, but it had to show patriotic Americans it wouldn’t allow anyone to criticize their loyalty or the national cause. This explanation probably referred to the mobs of outraged citizens who had attacked and even lynched people suspected of disloyalty.

It was in the Post’s best interest to support the law at the time. Had the editors been critical instead, the Sedition Act would have empowered the postmaster general to block all delivery of the Post, as he had with other publications.

Two thousand cases were tried under the Sedition Act, half of which resulted in conviction. It was invoked most often in Western states, where it was used frequently to prosecute members of what was considered a radical workers’ group, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

The Sedition Act was repealed in 1920 and the offenders were pardoned, though well after the war had ended. The U.S. attorney responsible for the pardons praised the government for detaining a number of dissidents in prison after the war “to set an example of firmness that will go down in history as a warning to those who in the future might be inclined to harbinger and harass the government.”

As much as the president would enjoy being able to legally silence his detractors, their public criticism is still protected by law.

Featured image: Shutterstock

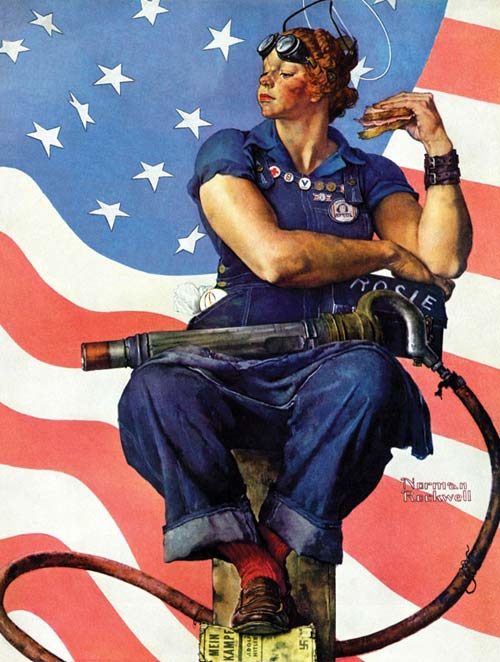

She Does Rosie the Riveter Proud!

In this 1943 editorial, an African-American woman describes her struggle to help America’s war effort.

A nurses’ aide in one of the Philadelphia hospitals tells us about one of her patients. The patient is a Negro woman, mother of several children. She is in the hospital recovering from terrible injuries received in an automobile accident on her way to work at a shipyard 20 miles away. She told the nurses’ aide how she got the job at the shipyard, as a welder.

“The foreman didn’t want me. He said I couldn’t learn it anyway. I told him, ‘I’m not after this job to take away any man’s work. I’m trying to work here because you can’t get men. You don’t want women in here, and I would rather do a lot of other things better. But you need people here and I can learn this welding.’ I did learn it too. Before I was hurt I could even read blueprints and follow ’em. Why, that foreman who didn’t want me to work for him came in yesterday to see how I am getting along!”

The nurses’ aide tells us that everybody in the ward hopes this particular welder will recover rapidly, because her one fear is that she will not be out of the hospital in time to see her ship launched. That ship represents an instrument of victory which she helped build after a struggle to get a job, a lot of hard study learning how to do it, and plenty of hard work at the welding itself. Her right arm is so twisted and deformed as a result of the accident that the hospital staff are not so sure this spirited and patriotic Negro woman will do any more welding. But they are going to do their best to see to it that she gets to the water front to see “her” ship go down the ways.

Sometimes we wonder whether expressions like manpower, absenteeism, incentives and essential workers do not get in the way. After all, there are a lot of “rugged individualists” around, pushing their way into war jobs, learning how to do new kinds of work, exhibiting that fine but intangible affection which the true worker feels for the fruits of his labor. This colored woman’s story reminds us that there are phases of the great uprising by American democracy.

—“Some People Defy Statistics,” Editorial, March 20, 1943

This article appears in the March/April 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

The Art of the Post: Rockwell Goes to War

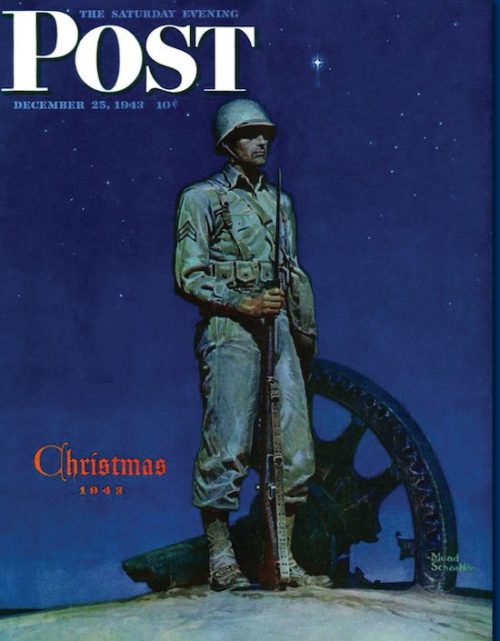

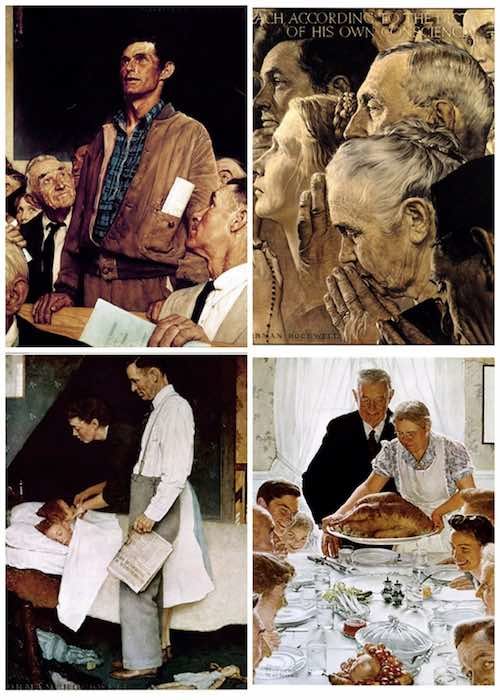

During World War II, two Saturday Evening Post illustrators, Norman Rockwell and Mead Schaeffer, wanted to aid their country’s war effort. They were too old to enlist, and neither one was physically suited to be a fighter, but they felt they might be able to help with their art.

The two artists decided to paint patriotic pictures and offer them free to the Department of Defense for fundraising and enlistment campaigns. They worked hard developing their preliminary drawings; Rockwell decided to illustrate Franklin Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” while Schaeffer chose a series of military themes. When they finished mapping out their ideas, the two took the long train ride from their studios in Vermont to the U.S. Office of War Information in Washington, D.C. The illustrators excitedly showed their proposals but met a frosty reception.

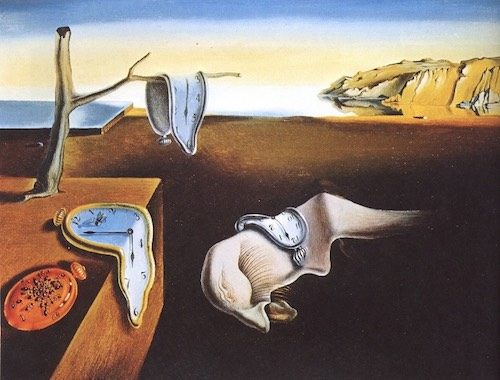

The Assistant Director of the Office was Archibald MacLeish, a famed poet, future Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright, and proud intellectual who didn’t think much of illustration. Rockwell recalled being told, “The last war you illustrators did the posters. This war we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.” MacLeish thought the military should use artists such as Salvador Dalí, Marc Chagall, and Stuart Davis to inspire the American public.

The Pentagon was not totally unsympathetic to Rockwell and Schaeffer. According to Rockwell’s autobiography, it offered them a consolation prize: “If you want to make a contribution to the war effort, you can do…pen-and-ink drawings for the Marine Corps calisthenics manual.”

Stung, the two illustrators took the long, depressing train ride home to Vermont. Schaeffer’s family recalls that when Schaeffer’s wife learned of the rejection, she spoke up: “To heck with the Army, why don’t you offer your pictures to the Post instead?”

The illustrators turned around and took the train back down to the Post’s offices in Philadelphia. There, editors reviewed the preliminary drawings and agreed to run Rockwell’s paintings as internal illustrations, followed by Schaeffer’s paintings in later issues.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms quickly became a national phenomenon. The Post received 60,000 letters about them. As editor Ben Hibbs later wrote:

The results astonished us all. … Requests to reprint flooded in from other publications. Various government agencies and private organizations made millions of reprints and distributed them not only in this country but all over the world. [Rockwell’s] four pictures quickly became the best known and most appreciated paintings of that era. They appeared right at a time when the war was going against us on the battle fronts, and the American people needed the inspirational message which they conveyed so forcefully and so beautifully.

It began to occur to government officials that they might have made a mistake rejecting the paintings. Belatedly, they tried to jump on the bandwagon. With Rockwell’s permission, the Treasury Department took the Four Freedoms on a tour of the nation as the centerpiece of a Post art show to sell war bonds. The paintings were viewed by 1,222,000 people in 16 cities and were instrumental in selling $132,992,539 worth of bonds.

The illustrations proved far more effective than anything else the government had planned. The Pentagon even sent a film crew to Vermont to stage a documentary about the illustrations, implying (falsely) that Rockwell and Schaeffer had been working at the behest of the government all along.

As for MacLeish, he did not last long in his job. Rarely has a misguided act of cultural arrogance been so promptly, resoundingly, and satisfyingly refuted.