50 Years Ago: JFK Conspiracy Coverup?

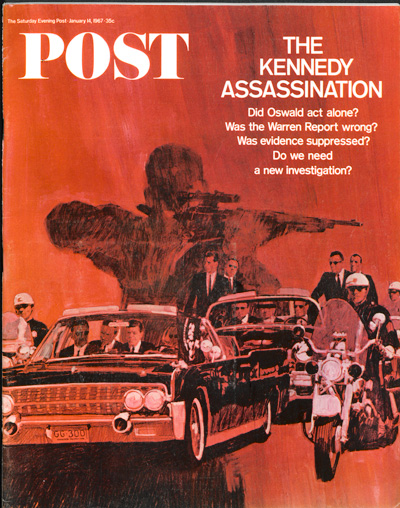

Three years after the Warren Commission released its report on the death of President Kennedy, many Americans didn’t buy its conclusion. The Post’s editors believed a new study would put the matter to rest

The last thing the country needs is a spectacular sequel to the Warren Commission, with reporters and cameramen swarming around, with every bit of evidence spread out before the public, and with all the conspiracy-mongers crying out their dubious speculations. Publicity and politics are both dangers to such an inquiry. It would be difficult to find anyone totally immune to the pressures that would inevitably arise — pressures to suppress the unpleasant, to cover up any mistakes, to leak conflicting versions of the evidence. Nonetheless, it would be a total rejection of our society to assume that we cannot create a fact-finding committee of indisputable impartiality, skill, experience, rectitude, and concern for the truth.

—“A New Warren Commission?” Editorial, January 14, 1967

The Unanswerable Question: Who Killed JFK?

There is no better example of Americans’ chronic suspicion of their government than the fate of the Warren Commission Report, released 50 years ago this week.

President Johnson requested a President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy within weeks of the shooting. Months later, the Commission presented its report which confirmed the official version offered by the Justice Department: A lone, crazed gunman, acting alone, killed the president.

America wasn’t buying it. Even before the Commission met for the first time, the majority of Americans no longer believed a lone shooter was responsible. A 1963 poll showed 52 percent of Americans believed a conspiracy was behind the assassination. Over the years, America’s faith in the Commission’s findings has fallen so low that a 1998 survey showed 90 percent of Americans believed a conspiracy was involved.

How wrong could the Commission be to earn such disregard? Was it incompetent, corrupt, or both?

In the Post article “The Kennedy Assassination” published in 1967, Richard J. Whalen addressed some of the reasons why the Report was so widely discounted.

First were the commissioners themselves: stolid, deliberate people—three senators, a congressman (Gerald Ford), a former head of the CIA, a former head of the World Bank, and the chief justice of the Supreme Court. It was a group unlikely to favor fantastic premises, or indulge their imaginations. According to Whalen, “The Chief Justice was understandably reluctant to assume the task forced on him by the President, for he was miscast. In a unique situation, demanding a supple and pragmatic, yet unswerving, truthseeker, he was a figure of granitic rectitude and decorum.”

Next was the questionable evidence. Medical records from the hospital disappeared, reappeared, then disappeared again. Some witnesses were ignored, others questioned at great length. Witnesses contradicted each other, and appeared inconsistent with what could be seen in the Zapruder film.

by Richard J. Whalen

January 14, 1967

Then the Commission began to divide over the “single-bullet” theory, which asserted that a single bullet caused multiple wounds to Kennedy and Texas governor John Connally.

“The arguing within the commission over the single-bullet theory continued until the Report was in its final drafts. Sen. Russell, Sen. John Sherman Cooper and Congressman Hale Boggs remained unpersuaded, and were at most willing to call the evidence ‘credible.’ Dulles, John J. McCloy, and Congressman Gerald R. Ford believed the theory offered the most reasonable explanation: Ford, for one, wanted to describe the evidence as ‘compelling.’ The views of the Chief Justice are unknown.

“[Pennsylvania Senator Arlen] Specter, Norman Redlich and other members of the commission staff unsuccessfully opposed the attempt to straddle this crucial question. They realized only too well, being closer to the evidence and the dilemma it posed, that it was indeed essential for the commission to find that a single bullet had struck both victims if the single assassin conclusion was to be convincing.

“Finally McCloy suggested a compromise [in wording]—“very persuasive” —and this fundamental difference of opinion was fuzzed up in the final language of the Report… The shaky evidence beneath the commission’s findings goes deeper than the hedged and flatly contradictory expert testimony on the single-bullet theory.”

Whalen concluded that “the very foundation of the commission’s account is built on disputed ground.” The Commission’s unwillingness to investigate inconsistencies in the autopsy didn’t mean there had been a conspiracy to kill Kennedy, but it certainly gave the appearance of a cover-up.

The “hard evidence”—the physical, forensic evidence from the shooting—still indicated Oswald was the killer, Whalen wrote. But the “soft evidence”—the theories and conjecture— “tends to support the possibility of a second assassin. Why not, then, face in that direction and weigh every shred of evidence, old or new?”

It seems a modest, reasonable request. America only wants the truth. Give us the facts. But the facts in this case never seem to fit together. Instead of answers, questions just lead to more questions. After a half century of examination, the truth of the assassination seems more elusive than ever.

In 1967, Whalen suggested a special joint committee of Congress could put to rest many of the questions about the assassination. Such a committee convened in 1979: the United House Select Committee on Assassinations. It concluded that a conspiracy might have existed, but would say nothing more definite. In 1992, Congress began releasing the internal files of the Select Committee to the public in 1992, but it has not yet led to any conclusive answers.

And so we’re left with the incredible conclusion of the Warren Commission: a lone gunmen seized an opportunity to shoot the president, and succeeded. He was quickly arrested, but killed by another lone gunman before he answered any questions. It hardly inspires belief. Yet the alternative explanations are even more fantastic.

Given the country’s emotional investment in the death of Kennedy, it’s possible the Warren Commission could never have succeeded. It was trying to answer the question “Who shot the president?” when the country wanted to know “How could something like this happen?” And it never addressed the larger question: How could a government that couldn’t even protect its chief executive from a solitary maniac be trusted to investigate his death?

Click here to read “The Kennedy Assassination” by Richard J. Whalen, January 14, 1967 (PDF).