Saving Our Dying Waters — 50 Years Ago and Today

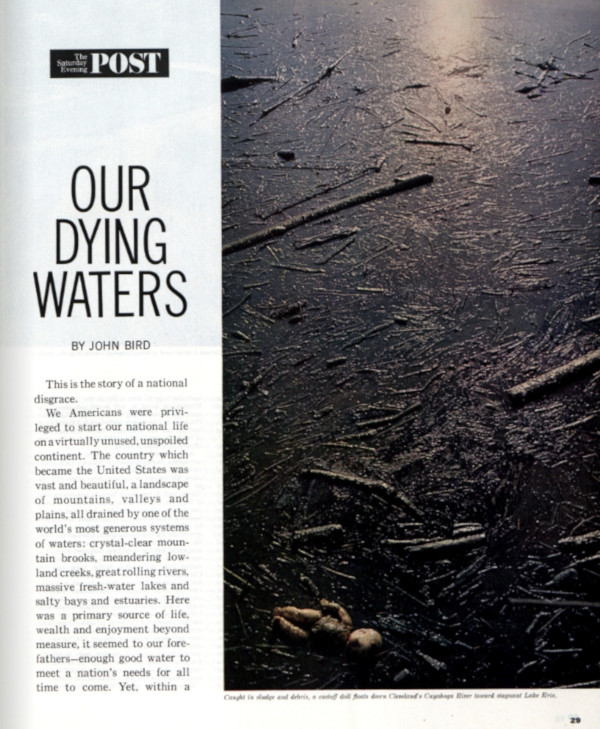

On a bright Sunday morning in June 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire. An oil slick atop the river caused by years of industrial waste burned with flames reaching over five stories. Three years earlier, on April 23, 1966, this magazine published an article by John Bird titled Our Dying Waters. Bird outlined the issue of America’s contaminated rivers and what needed to be done to fix them, claiming “the 21st century will be well underway before we are ready to cope with 20th-century pollution. We may choke on our own filth by then.” More than fifty years later, have we made any progress?

The outrage that followed the burning of the Cuyahoga spurred public support for political action, leading to the Clean Water Act (1972) and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970). Dying Waters emphasized the lack of regulation and outdated processing plants that heavily increased the amount of pollutants in water. Since the 1966 article, some progress has been made. The various acts that were passed increased testing of rivers and public water supplies and required closer monitoring of industrial waste. Regulated pesticides, less industrial water pollution, and more marine sanctuaries put an end to flammable rivers.

Unfortunately, contamination of rivers and reservoirs is not fully a thing of the past. An EPA report published in 2008 found that 46 percent of this nation’s rivers are in poor biological condition, leading to a loss of fishing and recreational facilities. This study reported that 24 percent of rivers have heightened levels of bacteria that “are indicators … of the possible presence of disease‐causing bacteria, viruses and protozoa.” Along with elevated phosphorous levels, mercury in fish, and loss of coastline wildlife, this report claims that “Our rivers and streams are under stress.”

The EPA introduced several methods of improving the biological condition of our rivers. The authors planned on investigating the source of the stressors, “including runoff from urban areas, agricultural practices and wastewater,” however no follow-up report has been published.

This sort of study did not exist in the time of Dying Waters, so it is unclear how the rivers of today compare to Bird’s. The major difference between now and 50 years ago is attention and regulation. Where there were no federal laws against pollution before the EPA’s creation in 1970, we have government agencies designed to test industrial waste. Where environmental disasters went unnoticed, we have contaminated drinking water making national headlines for weeks on end.

In his article Bird states that “We have taken it for granted that the water flowing from our faucets is free of disease, but we couldn’t be more wrong.” Today, roughly 25 percent of Americans drink from water supplies that violate the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974). Bird mentions the problems caused by salmonella infected waters in 1960. While there were no water-born salmonella outbreaks in 2015, 77 million people drank from water contaminated with coliform, nitrates, lead, copper, radionuclides, arsenic, and other contaminants. The 1960 residents that drank salmonella-contaminated water contracted high fever and nausea. Water quality in 2015 may have contributed to any number of ailments for the drinker from nausea and fever to cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Local and national attention surrounding Flint, Michigan, provides an excellent example of the nation’s ongoing water crisis. While the issue of lead contaminated water is relevant now (18 million people were drinking from lead-contaminated sources in 2015), lead was not even mentioned in Bird’s article. The true dangers of lead poisoning were not understood until the early 1970s.

The focus today has expanded to include water conservation as well as pollution. In 1966, the nation used 314 billion gallons of water per day. Now, although our population has increased by 68 percent, our water use has grown by only 2.5 percent to 322 billion gallons. While this is far better than the 1 trillion gallons Bird predicted the nation would need (the closest the country had come to that amount is using 435 billion gallons per day in 1980), it is still not a sustainable amount of water. While population continues to grow, the world’s water supply remains fixed. Statistics published by the United Nations predict that two thirds of the world will live in “water-stressed” countries by 2025 if current patterns of water-use prevail.

The facts are there: continuing to treat our water the way we have in the past puts millions of people at risk in addition to endangering aquatic environments. The article provides some hope for the future, emphasizing big picture ways of saving our dying water. Today there are many ways that everyday people can make a difference in our water crisis, we need only try. As Bird wrote half a century ago, “The only unknown is how long it will be before it’s too late.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Weekly Checkup: How Much Water Should I Drink?

We are pleased to bring you “Your Weekly Checkup,” a regular online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

We’ve all heard the admonition, “Drink eight 8-ounce glasses of water each day for optimal health,” with a further warning that it must be water — not coffee, carbonated beverages, or other fluid sources. That amount equals two quarts or half a gallon of water daily. It’s hard to trace the source of the advice, or to find credible scientific evidence to support it. How are we even to know to whom this caveat applies — sedentary older folks or normally active people working in offices and exercising several hours each week? Young or old? People living in temperate or hot climates? Healthy or sick individuals? Athletes or couch potatoes? Nevertheless, it is common to see people in every category lugging around bottles of water, sipping and slurping throughout the day as they engage in their normal activities.

That’s a lot of liquid. For what reason? Because our bodies are about 60% water, supporters claim a wide range of health benefits from drinking such large quantities of water: reductions in cancer, heart disease, constipation, fatigue, arthritis, angina, migraine, hypertension, asthma, dry cough, dry skin, acne, nosebleed, and depression; improved mental alertness and weight loss. But solid proof is lacking for most of these.

Can there be harm from drinking so much water? Probably not, except for infrequent cases of causing a low sodium concentration in the blood, ingesting pollutants in the water, or maybe a guilty conscience for non-achievers.

So, how much water is enough? It depends…

Some situations require additional fluid intake:

- athletics

- illnesses causing fever, vomiting or diarrhea

- living in a hot, dry environment

- high altitudes

- long plane flights

- kidney stones

- pregnancy or breast feeding

For the rest of us, if you rarely feel thirsty, and your urine color is normally pale yellow, you’re probably getting enough fluid. The fluid can come in any form: tap or bottled water, coffee, tea, soft drinks, milk, juices, beer (in moderation), and even in foods such as watermelon and spinach.

What advice is reasonable for healthy adults living in a temperate climate, performing mild exercise? Listen to your body! If you’re thirsty, drink. Advocates like to advance the dire threat that feeling thirsty means you’re already dehydrated. However, that alarm lacks credibility since feeling thirsty precedes actual dehydration, so there’s time to prevent it. If you’re not thirsty, there’s no need to drink, unless you fit one of the special categories mentioned above. We have enough worries in life without adding one more!

Floating Toward Ecstasy: How One Man Overcame His Scuba Fears and Learned to Let Go

The fish are fine and all that, but the epiphany is the sensation of floating, of weightlessness. After two days in dive school, I know the term is neutral buoyancy, the state in which you are neither rising nor sinking, but that’s just the science. It’s like explaining why a fish is luminously blue, which doesn’t quite get to the wonder of it. Broad leaves of soft coral bend in the current, bowing in praise of my effort to inhabit their world. I hear the soothing susurrations of my own breath, and submersed just 40 or so feet below the surface, I have a feeling of mindfulness, of intense alertness within this aquatic womb.

“We ourselves see in all rivers and oceans,” wrote Herman Melville in Moby-Dick. “It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life.” Divers require no explanation. “I live to dive,” my instructor, Steven, liked to say. He was a Dutch expat who came for a visit when he was transfixed by the lapis lazuli sea in Playa del Carmen and decided he’d never leave.

When Steven first told me, I could see the water but I couldn’t relate, because after two days of watching videos and practicing in the pool of the Tank-Ha Dive Center, my first open-water dives made me want to go home. I hadn’t equalized my ears properly and felt the first atmospheric pressure like a vice-grip inside my skull. Once that resolved, an acute thought replaced it, that my life — my parents’ son, my wife’s husband, my children’s father — was hanging on a rubber thread linking my mouthpiece to my tank. One mistake or malfunction would set in motion a lot of logistics, such as how to transport the body and what kind of services and eulogies and, gee, I had meant to increase my life insurance, hadn’t I? It didn’t make me inclined to feel thanks for all the fish, and I even felt unkindly toward the divers who had all promised, every last one of them, “You’re gonna love it!” as if they’d been pledged to repeat the line as part of some fraternal code.

When I climbed back onto the boat 40-some minutes later, I was stressed, tired, and relieved, though the relief passed quickly as the waves started to make the boat, and my belly, surge and roll. Suddenly, even the briny smell of the sea was an unpleasant odor. “I’m feeling a little seasick,” I told Steven.

“You’ll be all right once we get back into the water,” he said.

Would he think less of me if I threw up or broke down? I might do either, or both.

Yet, I am a victim of a long-conditioned impulse to finish what I start, which runs on a continuum from the food on my plate to the ordeals that I enlist in.

Quitting, that is, wasn’t an option.

The Riviera Maya, south of Cancún along Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, was more of an ideal than an ordeal. The jungle spread out, dense and rugged, a backdrop to what had been carved out and tamed into a vast playground with a fine white beach for a sandbox and toys such as speed boats and jet skis, mountain bikes and ATVs. At all-inclusive resorts, escapists luxuriate on rafts and chaise lounges, in poolside bars and Jacuzzis.

The biggest town, Playa del Carmen, used to be the jumping-off point for Cozumel, the island that Jacques Cousteau, the father of diving, made famous in his early documentaries. In recent years, though, Playa, as it’s known, attracted those who liked its low-key attitude, and soon enough it had grown its own jamming central district of shops, bars, and restaurants owned and patronized by European and American expats and Mexico City transplants. Deeper in is a pueblo with real people and great prices. Within easy access are Mayan pyramids and ruins, eco-parks and caves, and freshwater pools under caverns called cenotes (see-no-tays) that are unique to the Yucatán.

After my four-day dive course, I decided to take a break from the water. I headed down the coast to Tulum, to see ruins of a once-great Mayan city and catch up with two mates, Macduff Everton and Charles Demangeat, who knew the Riviera Maya since before anyone called it that, when they were touring in a circus in the 1970s, Macduff as the knife-thrower, Charles as the human torch.

“How’s that work?” I asked.

“Trade secret,” one, or maybe both, of them replied.

They arranged rooms at Cabañas La Conchita, a bed-and-breakfast by the sea with thatched palapas around a sandy courtyard whose palm trees stand like architectural columns. There were no phones or TVs, and starting from 10 in the evening, no electricity, only candles and the music of the surf. The bright blue hammock on the patio lured me like a fly into a spider’s web, where once again I experienced that floating sensation. High above, a pair of big birds spread their wings and hung in the sky, as if they liked the view from that spot, and I probably hadn’t drifted off for too long because when I woke up, they were, improbably, still there.

Not too long ago, Macduff had published a splendid book called The Modern Maya: Incidents of Travel and Friendship in Yucatán (University of Texas Press, 2012). Charles, a writer and artist, spoke perfect Spanish and a good Mayan. They befriended a Mayan guide and herbal doctor named Candido, who offered to take us into the Sian Ka’an Biosphere, a 528,000-hectare preserve of tropical forests, marshes, rivers, and lagoons connected by a 15-mile canal cut by Mayans during their 1,200-year reign.

We piled into their rented compact and went in the mid-afternoon with Candido and his wife, Delfina, to a dock where they kept a motorized dinghy that skirted across some gloriously isolated lagoon, through a canal to another lagoon, until we reached a landing, the entrance to a jungle trail Candido bushwhacked for visitors like us.

The ground was soft, and trees, branches, and vines bent, twisted, and wedged into the canopy. Termite colonies grew like big black tumors on some trees. Other flora grew at every angle, along the ground, on other tree limbs, lurching for sunlight that struggled to penetrate the thick cover. The sun’s reflective glow on the foliage suffused the air with an emerald tint. There was a chirrup and steady crackle of insects, a busyness in this self-contained universe that you hardly noticed until it was broken by a coarse rustle, probably of some small animal, and that was followed almost instantly by a flutter of birds. What we were most aware of, though, were our own footsteps and the sound of branches brushing against one another as we pulled them back to carry on.

For all the shade, there was still hardly any reprieve from the moist heat, and the lagoon looked like a big refreshing pool as we sat on tree stumps and Candido told how the jungle was the raw material of the society. The wide leaves of palm trees provided housing, the roots and barks and tendrils gave medicine, and the world a context for rituals and customs. He was amused by the matapalo tree, or strangler fig, which attaches itself to mature trees with two arm-like vines and hugs the tree — to death. “Like a wife!” he teased. Delfina laughed, hugging him for a photo, like a matapalo.

We climbed back into the dinghy and retraced our route across the lagoon to another canal. At the entrance was a stone ruin that was once a Mayan customs house. It was one of 23 archeological discoveries in this UNESCO World Heritage site. Some date back as much as 2,300 years. Traces of blue-green paint on the wall, faded but visible, and small decorative flourishes carved into the walls were signs of the life that was here once.

On the way back, Candido showed us how to lay out our life vests flat like lawn chairs and drift on our backs in the current. He said he’d meet us down the canal. We flopped out of the boat and floated, just us and the fish, a gnarled mangrove to our left, a grassy savannah to our right. The world was in harmony. The late afternoon sun shared the sky with an almost full moon. The temperature of air and water was harmonious.

“I’m worried,” I said. “I’m so relaxed, I could fall asleep and drown.”

“Life,” Charles said sagely, “is full of worries.”

The plan was to hire a fisherman and see the Tulum ruins from the sea at sunrise, but in the morning the surf was churning, and I didn’t have any Dramamine. Then, good news. The fisherman, thank God, had twisted his ankle and couldn’t go, and I returned to drift in my hammock until the ruins opened.

We arrived ahead of the tour buses, so we had the walled complex of temples and palaces to ourselves and wandered around the perimeter on a rocky bluff above the sea. The Maya who dominated the region for more than 1,200 years were advanced, like many other ancient but later conquered people. They built massive pyramids, such as Chichén Itzá and Cobá, which for the Maya were temples rather than tombs as they were for the Egyptians. Their hieroglyphs show that they acquired a deep knowledge of abstract mathematics and of astronomy, producing a 365-day calendar based on their observation of the sun. Tulum, the only Mayan seaport ever excavated, was inhabited when the Spanish arrived in the 16th century.

Pale traces of colors still speckle some of the murals and frescos that once adorned the walls, giving hints of its past glory. On one lintel is a figure tumbling from the clouds. The signpost calls it the “Descending God.” Divers have called it the “Diving God,” though the Mayans cannot claim credit for scuba. I squint at it from behind a rope 15 feet away.

“You see the head?” Charles says, tracing the outline in the air. “There’s the body. You see it?”

“Yeah, yeah. I think so.”

“You can see it better on the internet.”

It’s hot, and we cool off with a pre-noon chelada (lime juice, beer, and ice; chela is a Yucatán slang for beer). Then we go to Gran Cenote. All the region’s rivers are underground, and as the water travels through limestone toward the sea, it forms the cenotes. The Maya regarded them as sacred, and so do many divers. They say the water is so clear that other divers look like they’re floating in mid-air, but this is cave diving, the sport’s equivalent to skiing’s double-diamonds, with a real risk of wandering into inadvertent darkness, and it takes some mastery to manage it safely. The more doable alternative is to snorkel in the caverns that have air pockets, and of these, Gran Cenote is considered among the best. You’re basically swimming in a hollow with decorative speleothems, natural stalactite formations on the walls and ceiling that, with some imagination, seem to transform into other shapes.

I was okay with snorkeling in the lighted areas, and even if I had had dive gear with me, I don’t think I could have willed my body to cross into the darkness.

I had, as I said, stuck with the scuba training mainly out of pride about finishing what I started. When I had planned this excursion, I had visions of actually entering the cenotes with scuba gear, but I quickly saw there was no way I was going to achieve anything so ambitious. Indeed, peering into that darkness, I no longer even wanted to. Now my goal shifted to something much more modest. I just wanted to get past fumbling with equipment and my own anxiety so that I could enjoy the diving and understand why people connect to something in the water. So, a few days later, I geared up and went back into the open water at a reef called Moc-Che.

After my third dive there, something clicked and my training earlier in the week started to kick in. I think it began when I realized the equipment was working and that I knew how to work it.

Once that trust was established, I began to feel it, and then the scales fell away from my eyes and I began to see stuff. A shoal of diaphanous white and yellow fish, two huge lobsters under a rock, two flounder playing dead on the sandy floor, an eel poking its face out from a hole in the reef. A big surly-looking creature passed, which was especially exciting later when I found out it was a barracuda.

By the fourth dive, I didn’t see why we had to get out of the water, since I still had at least five minutes worth of air in my tank.

“There were a lot more fish today,” I observed.

“No,” Steven said, “they were here yesterday.”

“Really? I guess I was more comfortable.”

“Listen, you only have to remember one thing, and you’ll be okay,” he said. “Whatever happens, just remember to keep breathing.”

It’s not, now that I think of it, a bad life lesson.

Todd Pitock is a regular contributor to the Post. His last article was “Storm-Chasing on Vancouver Island” in the September/October 2016 issue.

Make Vegetables Great Again!

American eaters can be truly adventurous, ready to try out a new restaurant, a new barbecue recipe, or a new foreign cuisine. We just aren’t adventurous enough to make fruits and vegetables a standard in our daily diet. According to a recent survey, only 4% of Americans are eating enough vegetables.

Perhaps our diet is still being shaped by our historic reliance on meats and starches. For so long, the American diet was restricted to what was immediately available. When fruits and vegetables went out of season, we had a choice: wait for spring or open a jar of preserves.

By the mid-1800s, though, iceboxes enabled some cooks to keep foods fresher longer. And when refrigeration made it to transportation and into the home, fruits and vegetables could travel farther and last longer before going bad. Although this gave the average American the ability to eat more vegetables, it didn’t give them much of a reason to.

Because getting fresh produce is one thing; knowing how to cook it well is another.

As food writer and restaurant owner George Rector points out in “Rhapsody in Greens,” vegetables are usually so overcooked that they arrive on the dinner table with little flavor or nutrition left. His informative and humorous 1935 article explains the proper way to cook a vegetable so it can be “as cheering to the soul as it is beneficial to the body.” He also encourages readers to try obscure greens, such as finocchio, fiddle-neck ferns, and beet tops.

Rhapsody in Greens

By George Rector

Excerpted from an article originally published on November 2, 1935

Thanks to scientists, everybody is now aware that you have to eat green vegetables to keep healthy. But science hasn’t bothered — which may be a good thing in a way, since you can’t cook with a test-tube mind — to be equally enterprising about ways of making green stuff as cheering to the soul as it is beneficial to the body. There is no sorrier sight this side of the grave than the standard vegetable plate. And yet its unappetizing presentation is as much of a “must” in modern life as gas for the car, not to mention its yeoman service in keeping the feminine waistline within the bounds of fashion, if not of reason.

Now You’ll Like Spinach

Vitamins and reducing between them have done for vegetables what Tex Rickard did for prize fighting. But the gastronomical angle has been shockingly ignored during the build-up, much as if falling in love were being widely recommended as merely good for the stunted ego. That kind of spectacle makes you see what foreigners mean when they complain that Americans eat what they’re told is healthful, with no thought of the taste. That doesn’t happen to be true, but in certain lights the evidence looks damning.

Spinach is the proverbially tasteless vegetable — in toy shops they even sell spinach toys for bribing the young into eating it — but it’s also true that peas and string beans and cabbage and carrots and all the other green vegetables can be, and often are, as dull as last year’s phone book and as subtly flavored as a cardboard box. The human palate, a finicky faculty which is more precious than rubies, has every right to rebel at wet green hay for food; particularly since it’s thoroughly unnecessary. There is too little understanding of the simple fact that cooking your spinach without water, except that which clings to the leaves, trusting in its own ample juices, retains the flavor essences that make it the joy of real epicures; or that cooking a ham bone with it cheers up both food and feeder; or that, to get into the fancier touches, chopping and creaming it or serving it with poached eggs and grated cheese as eggs Florentine will make the rankest spinach hater wonder where it’s been all his life. Any one of those dodges is a dramatic demonstration that green vegetables provide half the finest flavors known to man, but to get those flavors, you have to treat your raw materials like ladies.

Eating in Foreign Lands

Some travel for health, some for lack of something better to do, some because a travel agent sent them a folder about the joys of winter sports in Tierra del Fuego. But one of my reasons for going to distant places is the prospect of new things to eat. And vegetables are the gastronomic explorer’s long suit. Sheep, hogs, cattle, and chickens are more or less alike everywhere, and a national cuisine can throw variety into them only by varying the cooking process — it’s just a question of boiled sheep’s tails in Afghanistan and roasted sheep’s legs in Simpson’s-on-the-Strand. But, although I’ve since met it on Italian pushcarts in New York, I had to go to Italy for my first meeting with finocchio, that crazy plant which looks something like celery and tastes far too much like licorice; not an experience you want to repeat often, but all in a good cause. I don’t even know the names of some of those futuristic Japanese vegetables which are grand when cooked into suki–yaki, but when pickled in the fiendish Japanese fashion produce much the same effect as a Jerusalem artichoke soaked in kerosene and then left to ripen in the bottom of a fisherman’s dory for two months. I haven’t met the Polynesians’ poi in person, but someday I’ll be digging my left fin into a mess of it, served by a young lady in a grass skirt, and checking it off in my memory along with bamboo shoots and fiddle-neck ferns and the kind of peas that the French cook pods and all. Also I have still to meet the boiled hops which are said to be still eaten in little-frequented parts of England. My natural affection for hops and all their consequences leads me to look forward to that with some pleasure.

The Fiddle-Neck Fern as Food

Fiddle-neck ferns, by the way, show that this country of ours, in spite of all fads, fancies, and foreign aspersions, manages to retain a fundamentally sound attitude toward eating. The fiddle-neck fern is the young shoot of the ferns that grow in the Maine woods, cut by the astute native while still light green and tender, and cooked like greens; the name deriving from the fact that a young fern shoot is all curled up at the end like one of those rolled-up paper tubes they blow in your face on New Year’s Eve. They taste, simply and beautifully, like the soul of spring. Spring, of course, is the queen season of the year for dyed-in-the-wool greens lovers, as well as for poets and the manufacturers of tonics, and a man who has acquired a real taste in the subtle bitternesses of wild greens is well on the way to being a genuine and home-grown epicure. For him the return of the sun means the return of horseradish and turnip and mustard and radish greens, some of which, like mustard, are so bitter that they’re better mixed with something mild like chard — a stepping down of flavor which is only the proper treatment, like mixing Scotch with water. It’s a special taste, but no one is ever happier than a greens hound crawling round a vacant lot on a warm spring afternoon, wielding a blunt knife in the pursuit of young leaves of dandelion and mustard.

If pushed, he will put up with such domesticated but rare items as chicory and endive greens, and will babble by the hour about the glories of young beet tops. The amateur gardener naturally thins most of his beets, so the survivors can develop to the proper size for ordinary cooking. But he can probably afford to let a row or so grow a little further without thinning, till they’re around five inches high, then root up the whole works, tiny beet and all, wash it thoroughly, nip off the thready tail of the little beet — only the tail to keep from “bleeding” it — and cook the whole plant to the tender point in as little water as possible, along with the indispensable ham bone or piece of fat bacon. There is a distressingly rare dish which is as healthful as it is comforting. Sometimes you can get beet tops in the markets, but they’re seldom young enough to give you the last fine careless rapture of flavor, and besides, it’s the lingering sweetness of the miniature beet on the end which adds the crowning touch. Very young beet greens are available in the markets in the early spring and are most delicious when tenderly steamed and served au beurre.

When I think of how any and all greens are abused by the average cook, I feel like taking out a charter for an S.P.C.G. [Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Greens]. Ordinary greens are always more or less gritty, because the lady in charge didn’t know about washing them by soaking in gallons of cold water, with the greens floating on top and the dirt sinking far below to the bottom, and then not pouring them out with the water into the sink, but lifting them off the top. They’ll be flavorless because she drowned them in water while boiling, and then drained the water off. As I’ve already mentioned somewhat querulously, spinach needs only the water which clings to the leaves. And one of the better ways to handle kale and beet tops is to treat them as you would spinach: Cook them for five minutes with water that clings to the leaves, then drain and pitch them into an iron pan in which some fine chopped bacon — easy on the bacon — has been sizzled just enough to start the fat rendering well. Cover that tight, let the natural juices do the cooking until your greens are tender, and you have something as extra in its own way as fine old brandy.

Putting Steam to Work

When you’ve developed your courage by doing spinach without water, try peas with lettuce leaves and discover just how delicate the pea can be when properly educated. The best receptacle for this job is a heavy metal pot with a tight-fitting lid and a good six inches of depth — iron, copper or aluminum, it doesn’t matter so much if the metal is good and thick. Wash your shelled peas and allow as much water as possible to cling to them. Then put a tablespoon of butter, without melting it, in your deep pot and introduce the peas. Cover the peas with some large lettuce leaves that are dripping wet, clamp on the cover, set it over the low flame and let the water on the lettuce and the natural moisture of the peas work up a bland but efficient steam, then immediately reduce the heat. This method cooks everything to a point of tenderness you never met before. The lettuce is thrown away before serving, but its soul remains behind in the flavor. You may prefer to introduce some chopped onion before steaming or to dust the peas with a little sugar after they hit the pan — I recommend both — but don’t miss the main and significant point, which is the consequences of steaming, not boiling.

The more I fiddle with food, the more thoroughly I am convinced that steaming is the best way of tackling most vegetables. It keeps in vitamins and flavor both, which means that here is a process satisfying both dietitian and gourmet, who are usually clawing at each other’s throats. A capacious vegetable steamer belongs in every right-thinking kitchen, along with a drip coffeepot and a pepper mill and a wooden salad bowl anointed with ancient garlic and all the rest of my idées fixes in the way of cooking equipment. And a steamer with several compartments makes it possible to combine several vegetables, with a minimum of trouble. A mixture of peas, young lima beans, and string beans, piping hot from the steamer and covered thickly with heavy cream that’s been whipped just enough to start thickening, or that grand old American dish, succotash, which, in its finest version, consists of fresh lima beans and green corn cut off the cob, seasoned with butter, salt, and pepper after steaming and then cooked for a few decisive minutes in cream.

Steamed cabbage, doused with butter, salt, and pepper before serving, can alone cause revolutions in people’s attitude toward that plebeian plant — the kind of people who really get the horror of that melancholy statement made by Walter Hines Page, the wartime ambassador to England, to the effect that there were only three vegetables known in England, and two of them were cabbage. I always think of cabbage, though, as a shining example of how something intrinsically first-rate can get a bad name through mistreatment. The American male has every reason for his notorious affection for corned beef and cabbage, but, when it’s either neglected or ruined when attempted, he prefers to leave it as just a glorious memory. It may do no good at all, but here goes for the resurrection anyway: I know a man who can make corned beef roll over and make a noise exactly like Virginia ham when he bakes it, and when he combines it with cabbage, the stars in their courses stop rolling to take a sniff. According to him, the secret lies in starting your beef in cold water and never letting it reach a fast boil, just a gentle simmer for the period, somewhat under four hours, you’ll want for a five-pound piece, starting with cold water. And he insists on skimming the fat off the water at least twice during the boiling. The cabbage should be sliced across the bottom to cut loose the first layer of leaves, and then quartered. Half an hour before the beef will be done, in she goes, to simmer along with her soulmate; and I recommend including half a dozen grains of whole black pepper. English mustard as a relish for it is a universal note, but chopped onion sprinkled over the plat is a preference of my own that you might take to. It sounds almost too simple to go wrong on, but it’s a mortal fact that the results of misguided at- tempts often remind you of the cowboy in The Virginian who said, on trying the corned beef, that it felt like he was chewing a hammock.

Meet Bubble-and-Squeak

A first-rate version of this dish will make your wife look thoughtful after the second bite and admit after the third that it isn’t bad at all. When she’s been softened up, get her to throw you some bubble-and-squeak for Sunday breakfast. Cabbage boiled to death and potatoes ditto are two of the pillars of British civilization and two disgraces to a civilized nation, but the Englishman who first fried the two together was a genius — never mind the name. I first met the results in the days when Rector’s was booming enough to supply my father with a yacht — a two-masted schooner which floated quite as well as Mr. Morgan’s — named the Atlantic. One summer the Atlantic boasted a Portuguese cook who was nothing to boast of. The old gentleman was pretty finicky about food, as he had every right to be, and, at breakfast one morning, he was just telling me he’d made up his mind to fire the Portygee and get somebody who knew how to boil water at least, when in came the steward with a small platter of piping hot bubble-and-squeak. Father hung his nose over it a moment — it had been browned just right in a minimum of mixed bacon fat and butter — glanced suspiciously at a forkful, stowed it, swallowed it, rolled up his eyes, and instructed me to go out to the galley and tell the Portygee that his pay was raised five dollars a week.

Or, moving over into red cabbage, which isn’t quite comfortably domiciled in some sections of the country yet, combine it with apples and red wine — a German idea, and a beauty.

Shred an average-sized, firm head up fairly fine and bestow the shreds in that same tight-lidded, heavy pot we’ve been talking about, along with four apples pared and sliced, three tablespoons of butter, a quarter cup of vinegar, a third of a cup of sugar — brown sugar preferred — a teaspoon of salt, a light pinch of cayenne — that red-headed and indispensable devil — and a cup of any old red wine, domestic or imported. After that it’s just two hours of simmering in its own juices over a low flame — with the wine and the butter she can’t burn — and, when that gets to the table, you may begin to understand the Egyptians, who worshiped red cabbage along with Isis and Osiris.

The Romantic Tomato

In his pursuit of the higher life, the overmoral vegetarian is also apt to forget the ornamental properties of vegetables. Painters don’t. No painter ever goes for long without tearing off a still life consisting of three carrots, an onion, a big red tomato, and a basket of Brussels sprouts, thus emphasizing again the intimate connection between high art and a boiled dinner. Certainly this question of looks had a lot to do with the past of vegetables. The business of putting a pinch of soda in with green peas and beans to give them that awful Paris-green color I do not approve. I suppose eating with your eyes is all right if you like it, but my own tastes don’t run that way. But things like tomatoes and eggplant might never have got anywhere if they hadn’t been cultivated as garden ornaments because they were handsome, long before they reached the table. In its ornamental period, the tomato was known as a love apple — the name being an outrageous example of mistranslation. When the Moors first brought tomatoes into Sicily, the Sicilians called them pomi di Moro — meaning “Moor’s apples.” Then the French met them under that name, and thought they were saying, pomi d’amore, meaning “apples of love.” So it got into French as pommes d’amour, and into English as “love apples.” As a natural consequence, tomatoes got a wholly undeserved reputation as something good for making the girlfriend fall in love with you — and so, for all I know, the first man who ate a tomato and found it was delicious was merely trying to work up his nerve to pop the question. He was taking a desperate chance, just the same, because tomatoes were long supposed to be poisonous.

After which dazzling burst of scholarship, let me point out that, besides both being among the raving beauties of the vegetable kingdom, tomatoes and eggplants are naturally coupled in the betting by being natural partners in gastronomy. Tomatoes are approximately foolproof, but, in general, eggplant is even worse mishandled than greens. Frying it in butter, which is as far as most cooks get, is about as sensible as stewing a nice young broiling chicken. Its delicate sub-bitterness won’t stand such treatment. There’s a way of baking it sliced with lemon juice that does it justice, and eggplant Provençal, which rings in the helpful tomato, is one of the most princely dishes in the Continental cuisine.

Peel your eggplant or not, depending on whether you like the fairly heavy bitterness of its skin. Anyway, slice it crosswise into quarter-inch disks and sauté the slices gently for 10 or 15 minutes in butter. Jean Frenchman includes a shallot with them, and if you can get shallots, more power to you. Sauté your tomatoes cut in half the same way; the number of tomatoes depends on the size of your eggplant. Butter a big flat baking dish and line the bottom with slices of eggplant covered in turn with a layer of tomatoes. Salt, a light pinch of cayenne pepper, and a dusting of grated cheese. Another layer of eggplant ditto, another layer of tomatoes ditto and seasoning ditto. After it’s baked about an hour in an average oven, the liquid that oozes out of the vegetables will be pretty well cooked away and the top beautifully brown. I can turn vegetarian in the presence of this dish and dine on nothing else, if the supply holds out. Along the Riviera they use olive oil instead of butter, of course, and there’s a considerable load of garlic in the makings.

You can do as you like about the garlic, but the butter will richen things up more, even if it does make the sautéing a little trickier.

It’s all in giving your vegetables a break, allowing them a small portion of the same care and forethought that meats receive as a matter of course. Even the lowly carrot, which is so good for you and so dull to eat, can step out as carrots Vichy and go to town as brilliantly as Cinderella. That’s just steaming your carrots along with a bay leaf, draining and letting them cool enough to handle, then slicing as thin as possible and browning in butter, both sides. With a sprinkling of chopped parsley they’re as handsome as they are sweet and juicy. And don’t get the idea, by the way, that parsley is a mere ornament. The other day I did meet a very pretty and charming young lady with a boutonniere of parsley for nothing but ornament, but the fact is that its queer, half-acid, half-musty flavor is the secret of many a famous dish. The French throw in an extra wrinkle in doing carrots Vichy in Vichy water, but between you and me, that’s only an excuse for giving the dish a name.

New Ways to a Man’s Heart

The more you shop around in the inner arcana of cooking, the more you realize that somewhere, sometime, somebody has cooked everything cookable. It never occurs to the average mistress of a kitchen to explore the possibilities of braised celery and endive and lettuce, although the results may go far toward solving the problem of how to get green stuff into Junior, and, more likely than not, the family cookbook contains full instructions for all three. She never heard of the admirable practice of frying thin slices of cucumber in batter as a side partner for fish, or of stuffing a pared and cored cucumber like a tomato. She even allows such reputable country dishes as fried oyster plant, done much the same way as carrots Vichy — you may have to ask for salsify to get it in your town — and wilted lettuce to slide ignored into the discard. Wilted lettuce is a homely thing, native to up-country farmhouses, but it’s the best way of explaining why the conventional salad never took hold on the old-fashioned American cuisine. A bit of chopped bacon in a frying pan, sizzling to a brown, some sharp vinegar and a little sugar thrown in — stand away while she steams and sputters — and then the large leaves of old-fashioned lettuce tossed in and chivvied round in the hot mixture till they’re limp as a wet glove and a rich dark green. The bacon and vinegar and sugar combine into a barbaric symphony of clashing and yet harmonizing flavors, and the lettuce turns out comfortingly chewy and surprisingly suggestive of a second helping. A man who won’t eat cold salads can often be made into a wilted-lettuce addict, which hornswoggles him neatly and painlessly into his share of roughage and vitamins.

Much as I reprehend eating with the eyes, I must admit that there is something in making a vegetable look interesting, which is why a baked stuffed tomato is always regarded with such respect — although it’s good eating, too — and undoubtedly why artichokes have always been among the aristocrats of the vegetable world. The amount of nourishment you get from artichoke leaves could be put in your eye with no inconvenience whatever and, unless you regard them as I do — as a fine excuse for consuming Hollandaise or vinaigrette dressing — the only point is the fascination of pulling them apart leaf by leaf and finding one good mouthful of heart in the middle. That appeals to everybody who ever took an alarm clock apart as a small boy.

Romance and Artichokes

One of our customers in the old days at Rector’s even made use of them in his affaires de cœur. He was always in love with another girl, and, although he was rich and not bad-looking, he was unlucky in love and would come into Rector’s to brood over his troubles alone, parked solitary at a table, without a word to throw at a dog. During one of these private wakes of his, he happened to order an artichoke Hollandaise — and presently the whole restaurant was treated to the spectacle of this young man, totally unconscious of his surroundings, playing “She loves me, she loves me not,” with the artichoke leaves. It got to be a regular thing with every new girl. Maybe artichoke leaves come in pairs — I’m not botanist enough to know — but anyway, he was always coming out on “She loves me not,” even counting the tiniest leaves, and feeling much worse in consequence. Finally a waiter took pity on him and carefully removed one leaf before serving him.

From then on, he came out on “She loves me,” and he would walk out of the place with his head up and his stick swinging and a five-dollar tip left behind on the table, as happy as a little boy with a new pair of red-top boots. He can’t have got much of the flavor of his Hollandaise, which is one of the more delicate consolations for living here below, but then, you have to pay some penalty for being in love. And I suppose you also have to pay some penalty for living, in an age when science gets more attention than flavor. But when I get down to eating by theory, I’ll follow the principle laid down by Dr. Horace Fletcher, the old fellow who invented Fletcherizing and carried it so far that he made his disciples chew even milk thoroughly before they swallowed it. As that would indicate, he was something of a crank. But he did write these noble words: “Trust to nature absolutely. … If she calls for pie at midnight, eat it then.” I’d like to be there and have a piece with him.

You can find out more about the Rectors and their famed New York City restaurants at The American Menu.

Cut Flower Care

Brightening your home with beautiful bouquets is one of the perks of flower gardening, and there are techniques for cutting and preserving flowers so they stay fresh and beautiful for as long as possible. But these techniques can vary from flower to flower, depending on the type of plant. Roses, for example, like other flowers, are best cut in early morning or evening or on cool, cloudy days to minimize moisture loss. Remove leaves that will be below the water line. Cut the stems off diagonally to enlarge the absorption surface, and do this while the stems are immersed in water so they won’t be obstructed by air bubbles. Treat asters and snapdragons in the same manner.

Cut roses, daffodils, gladiolas, and irises when the flowers are in bud. They will open in the vase. Other flowers such as marigolds, delphiniums, and dianthus should be cut after opening. After cutting the stems with a sharp, nonserrated knife, immerse the stems in a pail of lukewarm (never cold) water and place in a cool spot out of the sunlight for a few hours. This will increase longevity.

Flowers with hollow stems, such as daffodils, delphiniums, and amaryllis, will live longer if you turn them over after cutting, fill the stems with water, then place a plug of cotton in the base and submerge the stems immediately in the vase.

Before putting daffodils, hollyhocks, hydrangeas, or poppies in a vase, singe the ends briefly with a lighted match. This will keep the milky substance in their stems from coagulating and blocking their water supply. It will also prevent the milky substance from entering the water and adversely affecting other flowers.

To prepare clematis flowers, pour boiling water on the stems and then place them in cold water. Additionally, like some people, these flowers prefer a little nip to stay happy. The Japanese dip them in an alcoholic beverage, such as champagne, for a few hours before putting them in a vase. We don’t know if they drink the champagne afterwards, but we don’t recommend it.

For bouquets with gladioli, cut the flower when the lowermost floret is opening, and remove a few buds from the top.

Other Bloom-Extending Techniques

Use products such as Floralife, a powder that is added to the water. Or make your own by putting flowers into a solution of one gallon of water with one can of clear soft drink added. Or by adding two teaspoons of a medicinal mouthwash. Others suggest adding an aspirin, a sugar cube, or some bacteria-killing laundry bleach.

To resuscitate wilted flowers, cut a couple inches off the stems and place in a few inches of warm water for a half hour; then put back into the vase with fresh, cool water. In a hot room, place some ice cubes in the water. Or place the flowers in a cooler room for a few hours.

And for that final touch to keep your bouquet looking spiffy, why not cheat a bit? Spray cut flowers lightly with an aerosol hair spray to prevent blossoms from falling. Let us know if this works!