Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: 8 Negative Thoughts that Interfere with Weight Loss

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

One of the first steps to changing your thinking is to identify thoughts that get in your way. Categorizing these irrational beliefs can lead to building a shortcut that will help lead to functional thinking and healthier behavior. Here are seven types of negative thinking that can interfere with weight loss.

1. All or Nothing Thinking

Did you go to bed as a late-night snacking bug and hope to awaken in the morning as a die-hard dedicated dieter? Motivation, drive, and excitement can be instrumental in helping us accomplish important goals such as losing weight. But when we look at things in a polarized way, we end up repeating cycles of weight loss and regain.

To learn more about how to combat this pattern of thinking, read Avoid “All or Nothing” Thinking.

2. Filter Focus

Some people filter out accomplishments and focus only on their deficiencies, especially those related to weight. An example would be ignoring the two pounds you lost, while focusing on a package of cookies you ate this morning. This viewpoint leads down a road of frustration and hopelessness, paved with the perceived tragedy of many failures. Don’t get me wrong, we do need to understand and evaluate our mishaps, but only if we also enjoy our positive attributes and success.

Learn how choosing to mainly focus on the positive aspects of life changes your outlook on every situation, the people you encounter, and yourself, in The Problem with Filter Focus.

3. Mind Reading

Mind reading can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us. Thinking this way can result in self-imposed pressure to prove something to a boss, sibling, spouse, or co-worker. As a result, we may eat to help relieve the stress caused by these feelings — or we may lose focus on weight-related goals.

Mind reading can directly impact health behavior if we make assumptions about what others think about our size, what we eat, or our competence using exercise equipment at the gym.

Learn how trying to be a mind reader can obstruct weight management by causing anxiety and concern over what others think about us in Stop Trying to Be a Mind Reader.

4. Catastrophic Predictions

The idea that you’ll never lose weight if you don’t do it now is a good example of a catastrophic prediction. This way of thinking creates enormous pressure to change. Although this pressure can yield results in the short run, it doesn’t work well as a long-term perspective. A now-or-never mindset builds resentment and is emotionally exhausting. You may believe that putting intense pressure on yourself to change NOW will eventually lead to healthy habits. But our minds don’t work that way.

5. Labeling

In most instances, labeling is a poor way of explaining our behavior. We are unintentionally reasoning our way out of a solution. In other situations, using labels can be a copout. When you label yourself stupid, lazy, disorganized, or lacking willpower, you’re saying you can’t change — and that lets you off the hook for managing your weight.

Read how Catastrophic Predictions and Labeling Won’t Help You Lose Weight.

6. Emotional Reasoning

Emotional reasoning permeates many areas of our lives, including relationships, career, self-image, and certainly weight management. Having a strong emotional reaction each time you see the scale move in the wrong direction may cause a surge of negative emotions that leads to irrational thinking. Maybe you vow to eat nothing all day forgetting that each time you try this it ends in disaster. Or perhaps you feel strongly that you’ll never succeed and, as a result, you stop trying to eat right or stay active.

Read The Problem with Emotional Reasoning.

7. Demands

If you want to manage your weight long-term, “shoulding” yourself is not the best strategy. It may actually prevent us from doing what’s important. Even if you have short-term success guilting yourself into action, this won’t be effective in the long run. Even if it worked, who wants to feel guilty or pressured all the time? Telling yourself you have to do something strips away your perception of freedom and can lead to feeling disgruntled and even angry.

If we want to make lasting behavior changes and feel good about it, we need to stop talking to ourselves that way. Be nice to yourself. A simple change in words can make all the difference.

Read Why Making Demands on Yourself Won’t Help You Reach Your Goals.

8. Rationalization

Instead of blaming themselves for everything, some people blame others or their situation in life. Sometimes we come up with complicated explanations for our behavior so we don’t have to take responsibility for it. Yes, we do live in a culture that promotes weight gain and inactivity, but we still have choices. Some rationalizers are the defensive, angry types and others are intellectuals, debating like high paid defense attorneys. Some of us have spent years “spinning” the responsibility of our actions to make it someone else’s fault when we can’t reach our goals. Always shifting the blame bogs down our ability to achieve health goals.

Read Rationalization — It’s Not My Fault.

Healthy Weight, Healthy Mind: Gaining Weight After Quitting Smoking

We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017). See all of David Creel’s articles here.

This week’s column is based on a question from a reader. Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Reader Question: Help!!! I am one of those older women who finally quit smoking and find myself twelve pounds heavier. I eat the same way I have always eaten, although not necessarily the healthiest. All the weight is in the midriff/waistline area. I am so uncomfortable I can barely bend down. I hate the word diet, but I need to do something that I can hopefully stick to. Can you help?

First of all, congratulations on your persistence with quitting smoking—what an accomplishment!

Although smoking cessation often leads to weight gain, the net effect is generally a great improvement in overall wellbeing. One large study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed gaining weight after smoking cessation did not offset the beneficial effects on heart health.

But to your point, weight gain is something few desire, and gaining fat around our organs is related to increased risk of diseases. The obvious, ideal situation is to remain tobacco-free while maintaining a healthy weight.

Although there might be a slight change in metabolic rate after quitting smoking, it appears that increased appetite is more to blame. Although it might not seem like your eating has changed since you stopped smoking, sometimes these changes are so subtle we don’t recognize it. Consuming only 100 calories more than we burn each day can lead to 10 pounds of weight gain in one year. So, to your question—what’s a person to do?

There is no perfect diet for weight loss. In order to lose weight, we must create a calorie deficit. Many different diets/plans can help you accomplish this. Unfortunately, successful weight loss is often short-lived because the plan is unrealistic or people struggle to commit to a new lifestyle. Although I don’t know anything about your medical conditions, limitations, or preferences, I usually encourage the following:

- Begin monitoring what you are doing—track your food intake and your physical activity.

- Identify problem areas such as mindless snacking, skipping meals and overeating later on, late-night eating, portion problems, dining out, eating too few vegetables, or low levels of physical activity.

- Focus on a few small changes related to improved eating and increased physical Perhaps you could start by walking an extra mile per day and decreasing your calories by 300-500 per day.

- Consider professional accountability with a registered dietitian, fitness professional, physician or mental health provider specializing in weight management.

- Monitor trends on your scale to help you figure out what is working.

- Lastly, be patient. Frustration and perfectionism can kill commitments before they ever begin.

Thank you for your question. We’d love to hear back from you in the future. Good Luck!

Weight Loss Advice from the 1930s: Eat Less, Exercise More

Topping most of our resolutions this year is a repeat from the past: weight loss. But who’s to blame for this obsessive desire to trim and slim our figure? Automation? Hollywood? Feminism? France? Here’s a 1934 doctor’s take on America’s ongoing weight-loss craze:

—

Pounding Away

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, September 22, 1934

Before the establishing our modern knowledge of diet, it was taken for granted that the shape anyone might have had been conferred upon him by providence, and the best one could do would be to make the most of it. There was little to be done in making the least of it. Nature creates human beings and animals in all sorts of forms and sizes. A Great Dane takes many a roll in the dust, but never achieves the slimness of a greyhound; a draft horse of the Percheron type travels many a mile pulling heavy loads, but never gets small enough to be a baby’s pony. Nevertheless, the basic framework can be modified as to the amount of upholstery. Every woman knows that she can, by suitable modification of her diet and by the use of proper exercise, cause the pounds to pass away.

No one has determined certainly the cause of the recent craze for reduction. Perhaps it was the outgrowth of criticism of the female figure that was popular in the late ’90s. The textbooks of the ’90s had much to say about corset livers and hourglass shapes. The preference for the boyish form may have been the result of the gradual change in the amount of clothing worn by women. The multiple petticoats and the heavy underclothing of the late ’90s began to give way to single garments in what was called the empire style. The styles have tended toward the slim figure, covered by less and less clothing. Perhaps the change was the result of the coming of the automobile; that, too, has been a most significant factor in the change of our body weight.

A Matter of Form

Walking, up to 1900, was the accepted mode of transport for the human body in the vast majority of circumstances. Then came the motor car. Today there is in this country one motor car for each five persons, and walking is gradually becoming a lost art. Walking used to be the form of exercise primarily responsible for burning up the excess intake of food. With the gradual elimination of walking and with the coming of the machine in industry, there has been less and less demand for energy in food consumption and more and more tendency toward maintaining a slim figure by a reduction in the consumption of food. The person who takes no exercise and who eats the diet that was prevalent from 1900 to 1905 will put on weight like an Iowa hog in training for a state fair.

The suggestion has even been made that feminism was responsible for increasing the popularity of women like men. Within the last quarter century more and more women have come out of the home and into various clerical, manufacturing, promotional, industrial, and statesmanlike occupations. No doubt, the bobbing of the hair and the binding and suppression of the breasts, as well as the thinning of the figure and simplification of the costume, were women’s response to the necessity for greater ease of movement and less encumbrance while engaged in such work. A fat girl gets lots of bumps from office furniture in modern designs.

Then came the war, and with it there was intensification of all these motivations; the war made serious demands on women. The slightly suppressed desires for freedom merged into strong impulses and urges that suddenly seized every feminine mind. What had been merely a somewhat languid interest suddenly became a dominating craving. Reducing became the topic of the hour, and the craze for reduction was upon us.

It has been urged by some that the final stimulus for slenderness was a sudden change in fashions promoted by the modistes of France. Be that as it may, the French women themselves never succumbed to the craze for emaciation as did their American sisters.

The French are far too sound a race from the point of view of feminine psychology to urge the cultivation of manly traits in their women. No doubt, the French fashions did incline toward women of somewhat thinner type, but the modistes did not, like our designers of costumes, adopt an all-or-nothing policy. Individualization in form and costume has more often been the mark of France, whereas standartization and uniformity have dominated the American scene.

American manufacturers of ready-made clothing, with the beginning of the 1920s, began to produce models for slim women, hipless and bustless. As the women went into the department stores to purchase, they found it difficult to obtain anything that would fit. They came out wringing their hands and crying that most famous of all feminine laments, “I can’t get a thing to fit me.” And when a woman cannot get a thing that will fit, she is ready to fix herself to fit what she can get. There were promptly plenty of experts ready to help her through the fixing process.

To Make the Person Personable

Advertisements began to appear of nostrums to speed the activity of the body and to lessen its absorption of food. Phonograph records were sold, giving explicit instructions regarding exercise and diets. The radio poured forth systematic calisthenics and played tunes for the performance of these motions in a rhythmical manner. Plaster fell from many a living-room ceiling while women of copious avoirdupois rolled heavily on the bedroom floor. The springs and frames of many a bed groaned wearily beneath the somersaults of some damsel of 170 pounds. Pugilists who had been smacked into insensibility on the rosined floors of the squared rings became heavily priced consultants for ladies of fashion and of leisure who embarked on programs of weightlifting: Department stores offered, in the sections devoted to cosmetics, strangely distorted rolling pins with which it was claimed fat might be better distributed about the person. Shakers, vibrators, thumpers, bumpers, and rubbers manipulated electrically, by water power, or even by gas, were offered to those who cared to try them.

Out of this turmoil came a demand for a scientific study of overweight, its effects on the human body, its relationship to economics, sociology, psychology, happy marriage, the maintenance of the home, and physical and mental health. In response to this demand, research organizations in many medical institutions began to study the factors responsible for obesity and the most suitable methods for overcoming the condition without injuring the general health. Whereas, in scientific medical indexes of a previous decade, an occasional article only might be devoted to this subject, the indexes of recent years show scores of records and reports in this field.

The Do-or-Diet Spirit

The first response to the craze for reduction, as I have said, was the development of extraordinary systems of exercise, with the idea that a woman could keep right on eating the same amount of food that she formerly took and that she could get rid of the effects of this food by excessive muscular activity. Quite soon the women found out the error of this notion.

Walking 5 miles, playing 18 holes of golf, or even 6 active sets of tennis does not use up enough energy to take off any considerable amount of weight. Even the playing of an excessively severe football game removes from the body relatively little tissue. A football player, it has been reported, may be found to weigh from 5 to 10 pounds less after a football game than he weighed before, but most of this loss of weight is merely due to removal of water from the body, which is promptly restored by the drinking of water after the contest is over. Actually, the terrific strain of one hour of football burns up not more than one-third of a pound of body tissue.

Thus reduction of weight is for most people simply a matter of mathematics, calculating the amount of food taken in against the amount used up. Reduction is a matter of months and years, not of days. The investigators have shown that it is dangerous for the vast majority of people to lose more than two pounds a week. A greater loss than this places such a strain on the organs of elimination and on tissue repair that its effects on the human body may be serious and lasting.

When women found that weight could not be permanently removed to any considerable extent by excess exercise, they began to try extraordinary diets. The diets first adopted were selections of single elements. They have been characterized as perpendicular rather than horizontal reductions. The phrase refers to the nature of the diet rather than to the effect on the human form. In a perpendicular diet, the partaker eliminates everything except one or two food substances and limits himself exclusively to these. In a horizontal diet, one continues to eat a wide variety of substances, but eats only one-half or one-third as much of each. Perpendicular diets are dangerous because they do not provide essential proteins, vitamins, and mineral salts. These will be found in a properly chosen diet which includes many different foods, but smaller amounts of each. So women began eating a veal chop alone, pineapple alone, hard-boiled eggs alone, or lettuce alone. The phrase “let us alone” best expresses the proper attitude to assume toward a woman on a perpendicular diet. The constant craving for food and the associated irritability make the woman on such a diet a suitable companion only for herself, and sometimes not even for that. Certainly, she is no pleasure around a home. Among the first of the books of advice to be published on diet was one concerned only with the calories. No doubt, successful reduction of weight was easily accomplished by the caloric method, but the associated weakness, illness, and craving for food soon brought realization that there was more to scientific diet than merely lowering the calories.

The next extraordinary manifestation was the 18-day diet from Hollywood. The exact origin of this combination does not appear to be known. Perhaps it appeared first in print in the columns of criticism of motion pictures of a well-known Hollywood writer. In her statements on the subject, it was said that the diet was the result of five years of study by French and American physicians, and that the diet would be perfectly harmless for those in normal health. If the French and American doctors spent five years working out the 18-day diet, they wasted a lot of time. Any good American dietitian could have figured out an equally good combination, and probably a much better one, in an afternoon. The vogue of the 18-day diet was phenomenal. Restaurants and hotels featured it in their announcements. Hostesses, anxious to please their dinner guests, called each of them by telephone to know which day of the 18-day diet they had reached and served each guest with the material scheduled for that particular meal. It was said that a Chicago butcher bragged that he had eaten the first nine days for breakfast.

The 18-Day Sentence

The 18-day diet had peculiar psychologic appeal. For the first few days it consisted primarily of grapefruit, orange, egg, and Melba toast. Melba toast, be it said, is a piece of white bread reduced to its smallest possible proportions; then dried and toasted so as to be developed into something that can be chewed. By the second or third day, when the participant had reached the point of acute starvation, she was allowed to gaze briefly on a small piece of steak or a lamb chop from which the fat had been trimmed. Then two or three days of the restricted program followed, and again, when the desire for food reached the breaking point, a small piece of fish, chicken, or steak could be tried. Thus the addict passed the 18 days, during which she lost some 18 pounds. Then, pleased with her svelte lines, she began to eat; three weeks later she could be found at the point from which she had first departed.

For years it has been recognized that human beings need magical stimuli in the form of amulets, powders, or charms to aid in the concentration necessary for success in love, religion, health, or business. The human mind needs some single object to which it may pin its hopes, its faiths, and its aspirations. Moreover, there was the psychological appeal of mob action. There was the desire to be doing what everybody else was doing at the same time. Then there was the thrill of competition. One could hear the addicts of the Hollywood diet asking one another, “What day are you on?” And the answer came back, “I’m on the tenth day and I’ve lost eight pounds.”

With the mystic appeal of Hollywood, land of mystery, with the psychological understanding of human appetite, with the introduction of the Melba toast, the Hollywood diet swept the nation.

The Calorie Gauge

The one thing necessary to reduce weight successfully in the majority of cases is to realize just how many calories are necessary to sustain the life of the person concerned and what the essential substances are that need to be associated with those calories. Most of us enjoy our food. We eat food because we like it, and we eat without thinking what the food will do in the way of depositing fat. The researches in the scientific laboratories that have been made in the past 10 years indicate that we eat more food than we need, particularly at a time when energy consumption is far less than energy production. It has been generally assumed that the weight of the body is definitely related to health. There are standard tables of height and weight at different ages for all of us from birth to death. It must be remembered, however, that these are just averages and that any variation within 10 pounds or even 15 pounds of these averages is not incompatible with the best of health in a person who inclines to be either heavy or light in weight as a result of his constitution and heredity.

There are two types of overweight: One … in which the glands of internal secretion fail to function properly; the other … due to overeating and insufficient exercise. The glands of the body, including particularly the thyroid, the pituitary, and the sex glands, are related to the disposal of sugars and of fat in the body. In cases in which the action of these glands is deficient, a determination of the basal metabolic rate of the body will yield important information. This determination is a relatively simple matter. One merely goes without breakfast to the office of a physician who has a basal-metabolic machine, or to a hospital, all of which nowadays have these devices. One rests for approximately one hour, then breathes for a few minutes into a tube while the nose is stopped by a pinching device, so that all the air breathed out can be measured. By appropriate calculations, the physician or his technician reaches a figure which represents the rate of chemical action going on in the body. A rate of anywhere from –7 to +7 is considered to be a normal metabolic rate. A rate of anywhere from –12 to +12 may be within the range of the normal for many people. If no other special disturbance is found, the physician is not likely to be concerned about the metabolic rate within such limitations. Rates well beyond these two figures, however, are considered to be an indication of failure in the chemical activities of the body — namely, either too rapid or too slow — and measures should be taken promptly to overcome the difficulty. If the basal metabolic rate is –20, –25 or –30, the physician will prescribe suitable amounts of efficient glandular substances to hasten the activity. Moreover, he will at this time arrange to repeat his study of the metabolic rate at regular intervals. He will watch the pulse rate and the nervous reaction of the person to make certain that the effects of the glandular products that are administered are kept within reasonable limitations. If, on the other hand, the basal metabolic rate is found to be +20, +25, or +30, he will make a study of the thyroid gland and will provide suitable rest, mental hygiene, and possibly drugs to diminish this excess action. Rarely, indeed, is a person with a metabolic rate of +25 fat; in most instances, such people are thin, sometimes to the point of emaciation. There are periods in life when the human body tends to put on fat. As women reach maturity, as they have children, as they approach the period at the end of middle age, there is a special tendency to gain in weight. Men are likely to spend more time in the open air, eat more proteins and less sugar than do women, and therefore are less likely to gain weight early. The common period for the beginning of overweight is between 20 and 40 years of age; in women the average being usually around 30. Among men, the onset of overweight is likely to come on eight to ten years later.

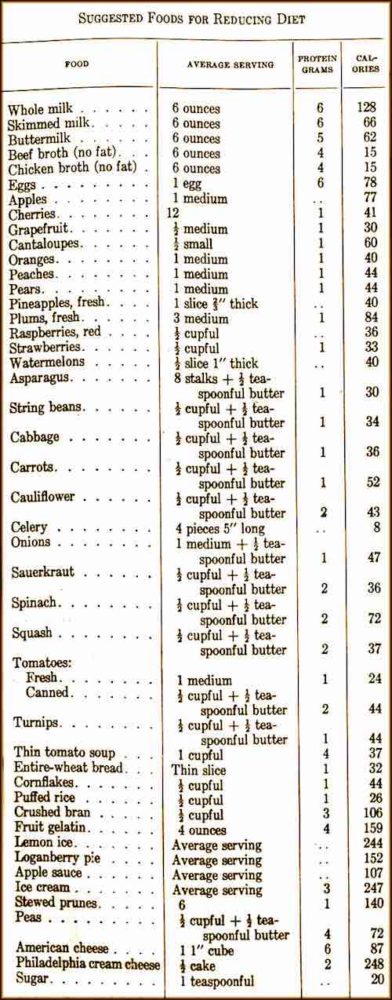

A man doing hard muscular work requires 4,150 calories a day; a moderate worker, 3,400; a desk worker, 2,700, and a person of leisure, 2,400 calories. A child under one year of age requires about 45 calories per pound of body weight, about 900 calories a day. The number is reduced from the age of six to 13 to about 35 calories per pound, or 2,700 a day; from 18 to 25 years, about 25 calories per pound of body weight may be necessary, or 3,800 a day. Thus, a person 30 years old, weighing about 150 pounds, may have 2,700 calories; a person 40 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,500 calories; a person 60 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,300 calories. A calorie is merely a unit for measuring energy values. In the accompanying table examples are given of the number of calories in various well-established portions of food.

Slim Picking

The overweight child at any age is quite a problem for the doctor. Most times it is the result of a family that tends to eat too much. Children of fat people are likely to be fat because they live under the same conditions as do their parents. If the adults of the family eat too much, the children can hardly be blamed for doing likewise. Investigators at the University. of Michigan say that the normal person has a mechanism which notifies him that he has eaten enough. Obese people require stronger notification before they feel satisfied, and many disregard the warning signal because they get so much pleasure out of eating. “Pigs would live a lot longer if they didn’t make hogs of themselves,” said a Hoosier philosopher.

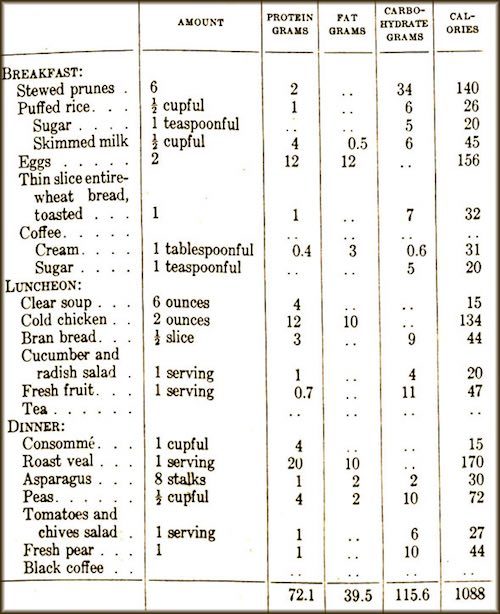

If a physician has determined that excess weight in any person is not due to any deficiency in activity of the glands, but primarily to overeating, it is safe to take a diet that contains a little more than 1,000 calories a day, and that provides all the important ingredients necessary to sustain life and health. A menu like the following, outlined by Miss Geraghty, provides about 1,000 calories as well as suitable proteins, carbohydrates, fats, mineral salts and vitamins:

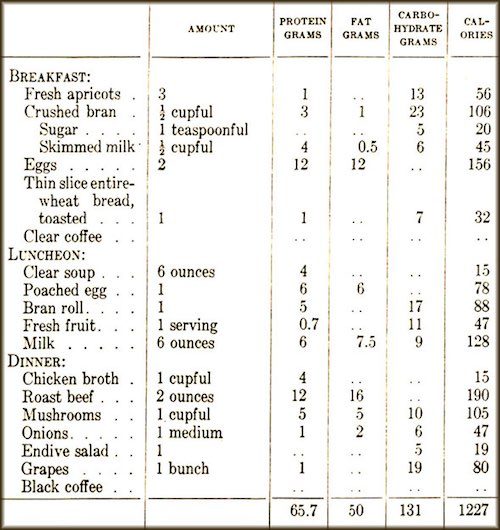

For those who want to reduce intelligently, here is another menu that includes all the important ingredients:

If you simply must have afternoon tea, add in 150 calories that the sugar and accompanying wafers will contain.

Every woman who has heard of these diets insists that they provide about twice as much food as she usually eats. This merely means that she is talking at random rather than mathematically. These diets do contain a wide variety of ingredients, but they are chosen with exact knowledge of what they provide in the way of calories and important food attributes. Quite likely, the women who protest eat a smaller number of food substances, but it is likely, also, that they eat so much of each of these substances that their calories are far beyond the total. Furthermore, they probably fail to keep account of the occasional malted milks, cookies, chocolates, or ice cream that they have taken on the side.

From the accompanying table of caloric values, it is possible to select a widely varied meal that will provide any number of calories deemed to be necessary; and if the meal is selected to include a considerable number of substances, it will have all the important ingredients.

In taking any diet, it is well to remember that calories are not the only measuring stick for food. A pint of milk taken daily provides many important ingredients. If bread, potatoes, butter, cream, sugar, jams, nuts, and various starchy foods are kept at a minimum, weight reduction will be helped greatly.

Over the radio and in a few periodicals that do not censor their advertising as carefully as they might, there continue to appear claims for all sorts of quack reducing methods. If only most people had some understanding of the elementary facts of digestion and nutrition, the promotion of such methods would yield far fewer shekels to the promoters. It is a simple matter to get rid of excess poundage and, in general, it is quite desirable. One merely finds out first how many calories per day constitute the normal intake, and tries to get some idea of the number necessary to meet the demands of the body for energy. One selects a diet which provides the essential substances and which permits some 500 to 1,000 calories less per day than the amount required.

Under such a regimen, steadily persisted in, the fat will depart from many of the places where it has been deposited, but not always from the places where it is most unsightly. For this purpose, special exercises, massage, and similar routines may be helpful. But persistence more than anything else is required. It is just a matter of pounding away.