The Deep South Says ‘Never’

This is the fourth installment in our six-part series, “The Long March on Washington.” In part one, “It’s Our Country, Too,” we looked at the limited wartime opportunities for black Americans in the 1940s. In part two, “Black Neighbors, White Neighborhoods,” we covered integration in neighborhoods throughout the 1950s. In part three, “Black Students, White School,” we reported on integration in the classroom.

“With all deliberate speed” was how the Supreme Court wanted American schools to integrate their classrooms. But in the years following their Brown v. Board of Education decision, little action had been seen.

By 1957, about 330,000 black children had been admitted to formerly all-white schools, but another 2,475,000 still awaited integration.

The Post looked into the reasons for such little progress in a five-part series, “The Deep South Says Never” by John Bartlow Martin (June-July 1957), which it proudly called “the most exhaustive and penetrating look at the problems of integration yet published in an American periodical.”

The Supreme Court’s decision had outraged many Americans in Southern states with segregated schools. Southern politicians spoke of protests, legal appeals, and outright refusal to comply. But there was yet no organized effort to oppose the federal mandate.

Then, one night in 1953, Robert Patterson, a farmer in Indianola, Mississippi, attended a meeting at his children’s school where he heard officials announce their all-white school would have to admit black students. Patterson was stunned. As he later wrote in a widely distributed letter to “fellow Americans,” “I gathered my children and promised them that they would never have to go to school with children of other races against their will.”

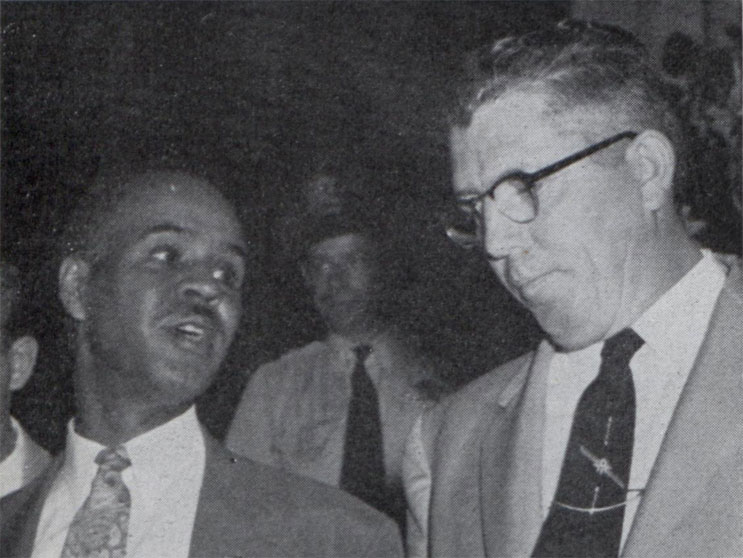

He began seeking like-minded citizens who could build public opposition to the federal order. When he and a handful of associates called a town meeting to address integration, he told Martin, “Everybody of any standing was there.” They agreed to form the Indianola Citizens’ Council, which started a movement that swept across the South to solidify resistance to integration.

At first, the Council aroused little interest among Southern segregationists because the federal government did not try to enforce integration. During this time, Patterson and his friends traveled to other towns, speaking to the towns’ service clubs of the need to organize opposition to integration. Soon, Citizens’ Councils were springing up in adjoining states.

The Councils didn’t content themselves with merely building public support for segregation. They were ready to apply financial influence to silence the voices for integration. As a council member told Martin, “The white population in this county controls the money. … We intend to make it difficult, if not impossible, for any Negro who advocates desegregation to find and hold a job, get credit, or renew a mortgage.”

The Council began applying its influence in June 1955, when black residents in five Mississippi cities petitioned local school boards to admit their children to all-white schools.

In Yazoo City, Mississippi, for instance, the Citizens’ Council published the names and addresses of all petitioners in the local paper. Roy Wilkins of the NAACP told Martin, “There were about fifty-three signers originally, and when [the Council] got through, only two signatures remained on it. One of them is living by helping his wife sell mail-order cosmetics—couldn’t get any work in town. One man had been a plumber for twenty years in Yazoo City, but he lost his business as soon as his name was in the paper.

“Wholesalers refused to supply a Negro grocer who had signed the petition, and a banker told him to come and get his money. He took his name off the petition, but it did no good. He left town.”

News that the petitions in all five cities were withdrawn encouraged the growth of segregationist groups in other states. By the end of 1955, one survey showed at least 568 local pro-segregation organizations in the South, claiming a membership of 208,000.

Council members were motivated by several reasons, though none admitted racism was among them. Some believed segregation was necessary to keep black men away from white women. (Patterson wrote protectively of “the loveliest and the purest of God’s creatures, the nearest thing to an angelic being that treads this terrestrial ball is a well-bred, cultured Southern white woman or her blue-eyed, golden-haired little girl.”)

Not all southerners supported these extremists. One Southerner told Martin he thought Council members were unintelligent and obsessed with interracial sex. “I once asked a council member, ‘What is your organization’s program?’

“He said, ‘To make people aware of the problem.’

“‘Do you think there is anybody south of the Mason-Dixon’s line that isn’t aware of it?’

“‘No.’

“‘Then what do you do at your meetings?’

“‘Well, we discuss the situation, discuss segregation.’

“‘It must get a little boring.’

“‘Well, yes, but we always get around to miscegenation.’”

Council members also felt they were fighting communism by opposing civil rights for blacks. Integration, they said, was a communist plot to stir up resentment in black Americans, who would rise up to destroy society. Patterson wrote, “If every southerner who feels as I do, and they are in the vast majority, will make this vow (to prevent integration), we will defeat this communistic disease that is being thrust upon us.”

What Patterson couldn’t have known was that the revival of aggressive bigotry in the South was helping to ignite a force in the black community. Black Americans were no longer waiting for the federal government to secure their civil rights, but had started taking action themselves.

Coming Next: The Rise of the Black Activists