Friends, Foes, and Formality: The Presidential Press Conference

Never, in its long and difficult history, has the relationship between president and press been so rancorous. Major newspapers are repeatedly challenging President Trump on his facts, and the president has referred to the country’s leading news sources as “the enemy of the American people.”

We’ve come a long way from Revolutionary days, when Thomas Jefferson said he’d rather have a free press and no government than a government and no free press.

Presidents have always worked to gain the approval of the press, knowing how newspapers can build public support for policies. But for most of our history, presidents kept their distance from reporters. In the 1900s, President Theodore Roosevelt began hosting informal press conferences, but he was selective of which reporters were invited, and he prohibited any reporter from quoting him. Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all held formal press conferences but would only answer their choice of questions, which had to be submitted in advance.

Franklin Roosevelt broke with tradition by inviting reporters into his office and answering questions directly, setting the precedent that is still followed.

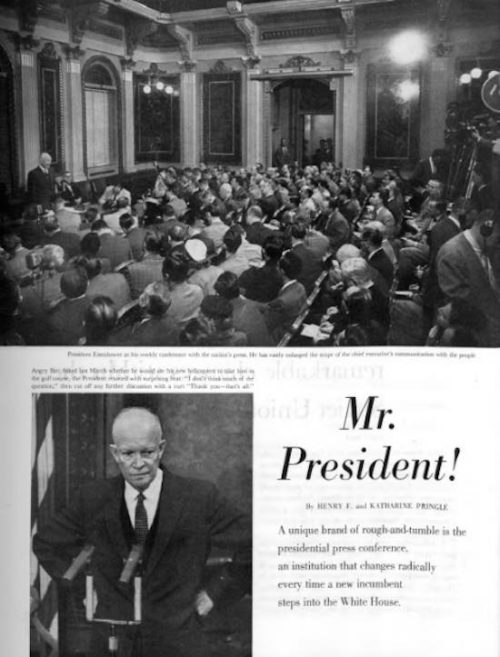

In “Mr. President!” Henry and Katherine Pringle offer a glimpse of a more decorous era in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s White House press room. It’s refreshing to read of the days when press and president could earn each other’s respect.

President Eisenhower had been dealing with the press since he was the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II. One of the chief reasons he was given that post was his ability to handle criticism and win support from his critics. Rarely did he show resentment or hostility toward people who fired questions at him. When he did speak his mind, he could show a dignified outrage, calling one question “the worst rot I have heard since I have been in this office.”

And to another, he gave what, for Ike, was a harsh critique: “I don’t think much of the question.”

Despite the occasional blunt response, Eisenhower appeared to respect the reporters, and they respected him. The current state of the White House press room is far different, and it seems unlikely that civility will make a reappearance anytime soon.

Smartphone Deniers

Sometimes I dream I’ve lost my iPhone. I’m adrift in the universe, cut off from my Facebook, Google, Twitter, email, texting, YouTube, livestream, and camera apps. It’s a terrifying prospect.

Like millions of Americans, I’m unashamedly addicted to my silicon-stuffed little slab. In just 10 years’ time, smartphones have managed to both transform and torture our culture (and me). These days, rather few of us can get to the morning’s first cuppa without reflexively checking in with our iOS- or Android-powered phone. Pathetic, eh?

Yet there are perfectly decent people — maybe you’re among them? — who dismiss smartphones, or even resent them. They just want to be left the hell alone by the millions of buzzing, beeping, and vibrating apps that are the signature of these pricey devices. Why? Because they don’t see the point of having massive processing power — not to mention GPS tracking — in the palm of their hand.

For some consumers, of course, cost is a hang-up, especially as you can grab a sweet little flip phone or bar-style model for under 20 bucks. Ramon Llamas, a market research analyst at IDC, which focuses on mobile-phone trends, told me the choice of a basic phone over a do-everything smartphone “really just comes down to one thing: cost.” Except that does not really tell the entire story.

Nancy Wintner, a veteran PR consultant in Pittsburgh, represents another perspective. “I have no interest in carrying my computer around in my purse,” she said to me, emphatically. She uses a bar phone that has limited functionality. “It meets my needs. I don’t feel disconnected from the world. I can always just pick up the phone and make a call.”

People like Wintner are not necessarily tech-averse outliers. They merely “choose to avoid the constant bombardment of information,” Bob O’Donnell, chief analyst at TECHnalysis Research, told me.

Others, according to O’Donnell, avoid smartphones largely because they cling to an old-fashioned notion of independence. “They’ve chosen to walk away from the overwhelming connectedness of modern life. It’s a retro thing.” These are the same folks who are drawn to the resurgence of vinyl records. “They are making a philosophical statement,” O’Donnell said.

Not surprisingly, one finds a diminishing number of smartphone users in the upper age ranges — but not by much. Until about the age of 75, O’Donnell said, people are generally willing smartphone users. After that, less so.

Someone like Snow Philip, a part-time journalist in Key West, Florida, is, at 74, right on the cusp. Philip owns a smartphone — it was a gift — but she’s packed it away. “I think it would complicate my life, which is full and rich. I don’t want to be as obsessed as everybody else, Facebooking and Twittering all the time,” she said when I called her on her landline. “It’s very unattractive to me.”

And then we have the last of the BlackBerry hangers-on, those stubborn few. Their devices today incorporate some smartphone-style goodies but are sparer by far. Among the most high-profile proponents is Michelle Kosinski, White House correspondent for CNN. Maybe you’ve seen her tapping away on her little BlackBerry in the White House briefing room. “I really love its simplicity and the [physical] keyboard,” Kosinski told me. “Emotionally, when I touch it, I think through it. And iPhone apps just annoy me.”

Most others in the White House press corps “have conceded defeat,” Kosinski said of the once ubiquitous BlackBerrys, but she’s in until the bitter end. Just in case, she’s stashed a bunch of older models in a drawer at home. “It may be the longest relationship I’ve ever had,” she said to me with a guilty giggle.

To those of us who love our phones to excess, Kosinki’s sentiment, though intended to be cute, has the sad, unmistakable ring of truth.

Cable Neuhaus writes about popular culture and media.