How to Cook a Muskrat and Other Wild Dishes from 1938

Squirrel potpie? Old news according to 1938 Country Gentleman author Jim Emmett, who was on the hunt for more unusual home-cooked fare. Stuffed raccoon, parboiled porcupine, and opossum roasting over an open fire were just a few of his tasty finds. Plus, a tip for foraged edibles: Fried or drizzled, wild greens go down best with butter.

A note to the 21st-century chef: Take these dishes with a grain of salt. Food safety has changed some in the 80 years since these recipes were published. To know what’s safe to eat — and, more importantly, what isn’t — in your area, seek out local wildlife and foraging experts.

Savory Dishes from the Wild

Originally published in The Country Gentleman, March 1938

Your ancestors, or mine, may not have endured Plymouth winters, trekked Midwest plains, or even been born in this country; still, there is a good bit of the pioneer in the make-up of most Americans. A joint of venison sent to the house is eagerly enthused over, we cook precious wild ducks and upland game birds with fear in our hearts that they may be spoiled in the oven, and even prepare potpies of squirrel or rabbit more carefully than we do expensive cuts of meat.

The eating of only certain wild animals is a habit passed down from days not so far back when a farmer stepped outside his door to shoot a deer nibbling apples from the tree he cared for so carefully. Naturally, with game so plentiful nothing but the best graced his table. Fat bear and young deer not only butchered quickly but yielded a large supply of good meat at the expense of a single charge of expensive powder and precious ball. Canvasbacks and mallards were preferred when the waters of every inland pond blackened at dusk with southbound birds, and trout from the pasture brook which appeared on the breakfast table then would be entered in fish contests now.

This preference for certain wild game seems also to be a matter of location. For instance, in the North, muskrat haunches are considered a delicacy by most French-Canadian families, and in the South, opossum is enthused over on the plantation owner’s table. Frog legs are preferred to chicken drumsticks in the Adirondacks, while on many a Tidewater-Maryland farm eels are a greater favorite than the oysters, crabs, and fish lying off the wharf for the taking.

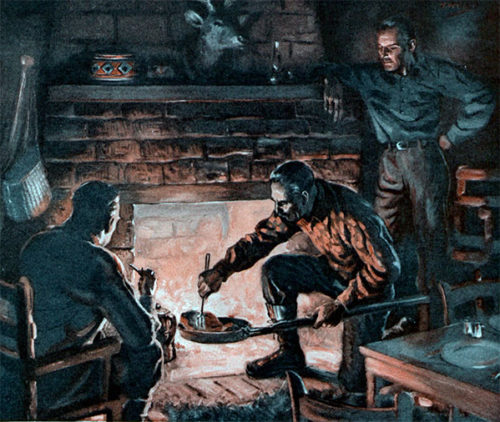

How to Pluck a Possum

The possum is more than an animal in the South; he is a distinctly American institution, and there the term opossum is considered an affectation. Many Northerners think of the possum as being eaten only by the plantation help. But those fortunate enough to sample the famed hospitality of the South, as it flourishes in rural regions, find that possum and sweet potatoes is also big-house fare. The chief difference is that the white folk bake theirs in an oven, while rural African Americans so often cook on the hearth with an open fire, suspending the possum on a wet string before a high bed of hickory coals. The twisting and untwisting string rotates the meat which is basted with a sauce of red pepper, salt, and vinegar. After having eaten possum cooked both ways, I prefer the open-fire method.

There are two golden rules to possum cooking: First, he is good only in freezing weather; secondly, do not serve without sweet potatoes. Preparation is not difficult, but like all wild things must fit the particular animal. Stick the possum and hang overnight to bleed. Next morning fill a tub with hot water, not quite scalding, and drop the possum in, holding tight to his tail for a short time so the hair will strip. It is then an easy matter to lay him on a plank and pull out all the hairs somewhat as one would pluck a chicken. After drawing, he should be hung up to freeze for two or three nights.

As a preliminary to cooking, place him in a five-gallon kettle of cold water into which has been thrown a couple of red-pepper pods, if you have them, otherwise a quantity of ground pepper. Remove after an hour of parboiling in this pepper water, throw water out, and refill kettle with fresh water, in which he should be boiled another hour.

While all this is going on, the sweet potatoes should be sliced and steamed. Take the possum out of the water, place in a large covered baking pan, sprinkle with black pepper, salt, and sage, and pack the sweet potatoes lovingly about him. Pour a pint of water in the pan, put the cover on, and bake slowly until brown and crisp. Serve hot, with plenty of brown gravy.

Haunch of Muskrat with Watercress

Muskrat haunches, usually with watercress, grace the French-Canadian farmer’s table often enough to guarantee their value as a worthwhile game dish.

Muskrats must be skinned carefully in order not to rupture the musk or gall sacks; those offered for sale on city markets are a trapper’s byproduct; often indifferent skinning spoils them for cooking. French-Canadians use only the hind legs or saddle, four animals for two servings. After a careful washing, they are placed in a pot with some water, a little julienne or fresh vegetables, some pepper and salt, and possibly a few slices of bacon or pork. After simmering slowly until half done, they are removed to a covered baking pan, the water from the pot is put in with them and baking continued with frequent basting until done.

In Maryland and Virginia, the muskrat is known as marsh rabbit and valued highly as a game dish. Cooks there use the entire animal, soaking it in water a day and night before cooking. Then follows 15 minutes’ parboiling, after which the animal is cut up and the water changed. An onion is added, with red pepper and salt to taste, and a small quantity of fat meat. Just enough water is used to keep from burning, thickening added to make gravy, and cooking continued until very tender.

Trade Thanksgiving Turkey for Roasted and Stuffed Raccoon

Coon is excellent eating if caught in cold weather. In skinning, be careful to remove the kernels or scent glands, not only under each front leg but also on either side of the spine in the small of the back. All fat should be stripped off. Wash in cold water, then parboil in one or two waters; the latter if age warrants. Roasting should continue to a delicate brown. Serve fried sweet potatoes with the meat. The coon, with its reputation of washing even its vegetable diet before eating, is one of our cleanest animals; he will not fail you as a cold-weather game dish if you observe the skinning precaution.

Parboiled Porcupine

In the North Woods the porcupine is a lost hunter’s stand-by, his emergency food supply. But unlike most emergency rations this inoffensive little animal is excellent eating, especially if young, when his flesh is as juicy and as fine flavored as spring lamb. The secret of skinning is to commence at the belly, which is free of quills; start the skin there and it pulls off as easily as that of a rabbit. Parboil for 30 minutes, after which roast to a rich brown or quarter for frying or stewing.

Fowl Cooking

The lower grades of ducks are acceptable eating if correctly prepared for cooking. All waterfowl, even the better ducks, have two large oil glands in their tail, put there by Nature to dress the bird’s feathers; these should always be removed before cooking.

The breasts of coot, rail, and young bittern are always worth serving. Cut slits in the removed breasts and in these stick slices of fat salt pork, then cook in a dripping pan in a hot oven. The rank taste of even fish ducks can be neutralized, unless very strong, by baking an onion inside and using plenty of pepper inside and out.

The meat fibers of all game birds and animals are fine grained, containing very little fat, even though the muscles themselves may be encased in it. For this reason most game recipes mention larding. This consists of laying strips of fat pork or bacon not only on top of the meat, but inserting them in slits cut in the flesh itself to prevent dryness. As a rule, dark-meated game should be cooked rare, so red juices, not blood, flow in carving. White-meated game should be thoroughly cooked. Animals and birds, tough or old, should be parboiled first; such meats are better stewed.

The Way with Turtles

Aquatic turtles are good eating at any time, old guides claiming their flesh has medicinal value. The common snapper is excellent, and preparing is not difficult. Aside from any humanitarian feeling, I do not like the method of dropping the live turtle into a tub of scalding hot water; I prefer to get that wicked head off as quickly as possible. One must carry the brute by its stocky tail well away from flapping trousers. Another man with an ax in one hand and a stick in the other extends the stick atop a convenient log. Hold the turtle near and snap go its jaws over the stick with a grip which never fails to make one realize what it would do to a foot or hand. With its neck extended, down comes the ax. One need have no qualms of pity when dealing with this enemy to wildlife.

After letting the turtle bleed, drop in scalding water, when the outside of the shell will drop right off and the skin can be easily removed. Then cut the supports of the flat undershell and remove it entirely, so the turtle can be easily cleaned. To save cutting the meat out, boil in its cleaned shell a short time, when the meat will drop off. Cut up, boil slowly three hours with chopped onion, or stew with diced salt pork and vegetables.

Freshwater Finds: Catfish, Carp, Eels, and Frogs

Proper preparation makes even our so-called coarse fish good eating. To skin bullheads or catfish, cut off the ends of sharp spines, split the skin behind and around the head, and from this point along back to the tail, cutting around back fin. Then peel two corners of the skin well down, cut backbone and hold skin in one hand while the other pulls the body free.

Carp should be carefully skinned rather than scalded. There is a layer of fat or mud between two skins and only with this removed will the fish be found good eating. Many people condemn catfish and carp as being soft fleshed; which they are if taken from too warm water. But every fish is better caught out of cold water.

Eels can be easily skinned by nailing through the tail at a convenient height. Cut the skin around the body, just forward of the tail, work edges loose, then pull down to strip off the entire skin. To broil, clean well with salt to remove slime, slit down back and take out bone, then cut in 2-inch pieces. Rub these with egg, roll in cracker crumbs or corn meal, season with salt and pepper and broil to a nice brown. To stew, cut in pieces after removing the bone, cover with water in a stewpan, and add a teaspoon of vinegar. Cover the pan and boil half an hour, then remove, pour off water and drain, add fresh water and vinegar as before and stew until tender. Finally drain again, add cream for a stew, season with salt and pepper only, and boil a few minutes to serve hot.

Smothered catfish is beloved [in the South], utilize this ugly but sweet-fleshed fish to advantage. Place a large skinned catfish in the baking pan and slice onions to put on top along with strips of bacon. Sift flour lightly over all, salt and pepper, and place in a heated oven 15 minutes.

Frog’s legs are a delicacy from the first spring days until freeze-up time. The northwoods hunting-camp cook soaks the hind legs an hour in cold water, to which vinegar has been added, as a preliminary to cooking. He then drains, wipes dry, and places them in a skillet of bubbling hot cooking oil. Some Southern tidewater shooting-camp cooks use the entire frog, other than the head; others grill the legs only. A preparation is made of three tablespoons of melted butter, half a teaspoon of salt, and a pinch of pepper. The body or the legs are dipped in this, rolled in crumbs and broiled three minutes each side.

Foraging Plants from Field and Woods

Not to be outdone, our early spring pastures and fields offer many edible greens free for the gathering. Dandelion greens, with a piece of bacon, are still regarded by many as a sure sign of spring. Milkweed shoots, wild mustard, dandelions, dock, and sorrel should be dried immediately after washing, then boiled with salt pork, bacon, or other meat. If on the old side, parboil first in water to which a little soda has been added, then drain before boiling again in plain salted water.

Perhaps you have cooked these wild things and not been satisfied with the results. Try chopping the boiled greens fine, then putting in a hot frying pan with butter, pepper, and salt, and stirring until thoroughly heated.

The tender stems of young brake or bracken [fern], cooked same as asparagus, are equally as good as that much-sought-after vegetable. The plants should not be over 4 inches high when they will show but a few tufts of leaves at the top; if much older they are unwholesome. Wash the stalks, scrape, and lay in cold water for an hour. Then tie loosely in bundles and put in a kettle of boiling water to boil three quarters of an hour, when they should be tender. Drained, laid on buttered toast, dusted with pepper and salt, and covered with melted butter they are as good as asparagus, some claim even better.

Wilted dandelion greens call for a peck of fresh tops and half a dozen strips of bacon. Fry the bacon until crisp, then crack into small pieces and pour with drippings over the washed leaves.

Botanists tell us over a hundred edible plants grow wild in our fields and woods. While we may find it easier to raise cultivated vegetables than to gather wild things, it is good to know we live where Nature offers this wholesome fare.