The Art of the Post: William A. Smith —The Artist Behind Enemy Lines

The Saturday Evening Post has always taken pride in the authenticity of its illustrations. Before the age of television, readers across the country learned about the history and customs of foreign lands from those colorful pictures. Even Hollywood movie studios relied on illustrations in the Post when designing costumes and backdrops.

Illustrators worked hard to achieve that authenticity, but none of them achieved it the way William A. Smith did.

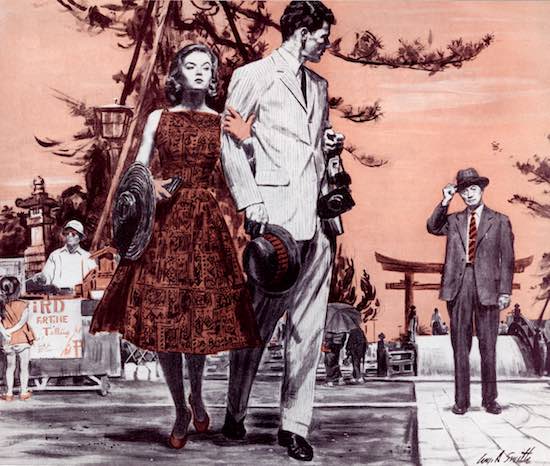

Smith was often called upon to illustrate stories about Asia. He seemed to have a special knack for the people and culture.

What readers didn’t realize was that Smith learned about Asia firsthand by serving behind the lines during World War II for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor to the CIA. He served in China for the duration of the war, often traveling clandestinely around the country.

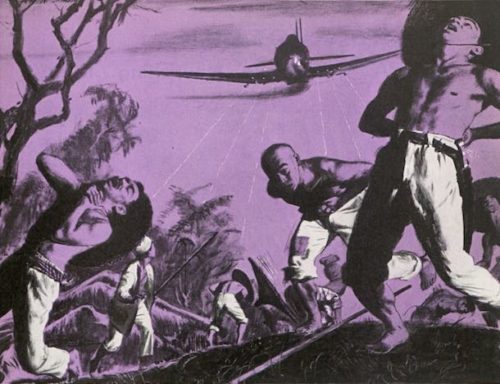

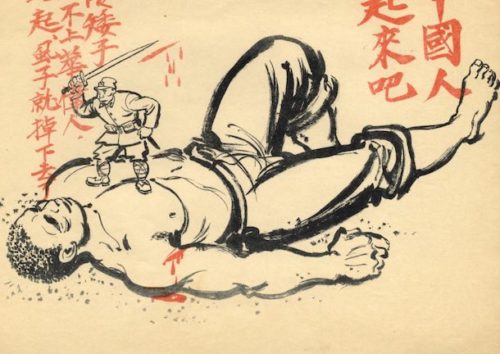

One of Smith’s roles as an artist for OSS was to create a series of propaganda drawings to support the Chinese in their war with the Japanese invaders.

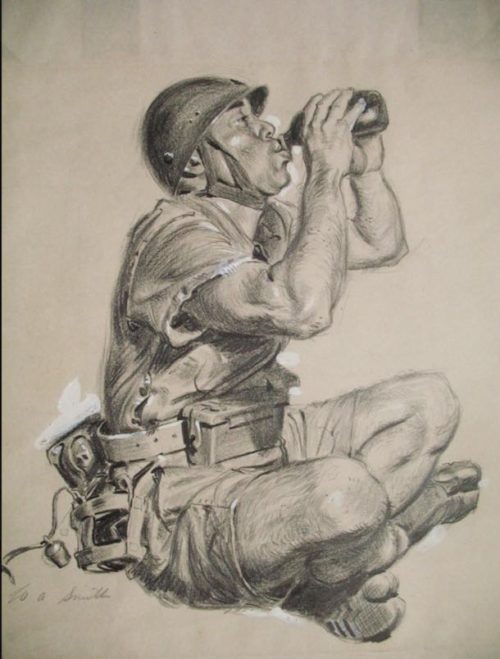

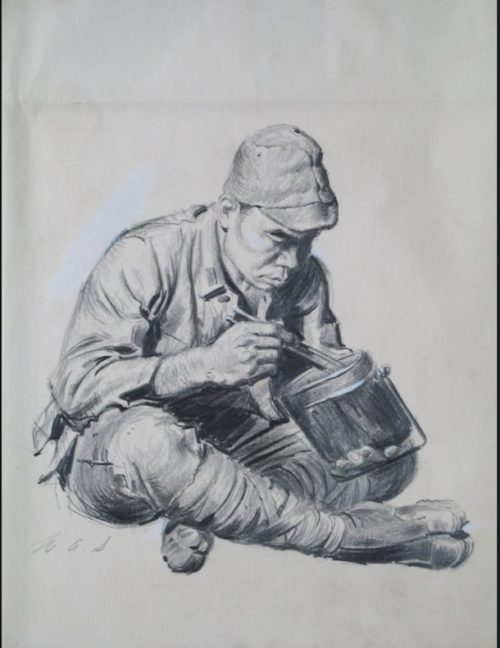

He also spent time working in Weihsien prison, a POW camp operated by the Japanese in Shantung Province, China, during World War II. The prison held 1,500 civilians — British, American, Belgian, and Italian — for over two years before it was liberated. Smith sharpened his skills sketching the Japanese guards there.

Smith described how the OSS helped capture the prison from the Japanese:

Only one Chinese was permitted inside the high brick wall. He was a dirty and stupid acting coolie whose job was to remove the pails of refuse from the latrines. Japanese would have no part of this job. Actually, he was an OSS agent and his access to the prison made it possible for the prisoners to communicate with the outside. … The other internees were most surprised when, after the Camp had been taken by the Americans, the same Chinese walked through the gates in a Western-type business suit.

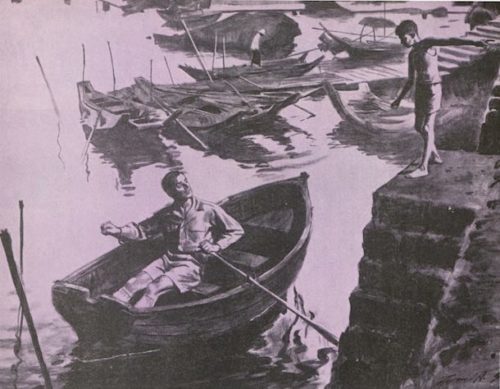

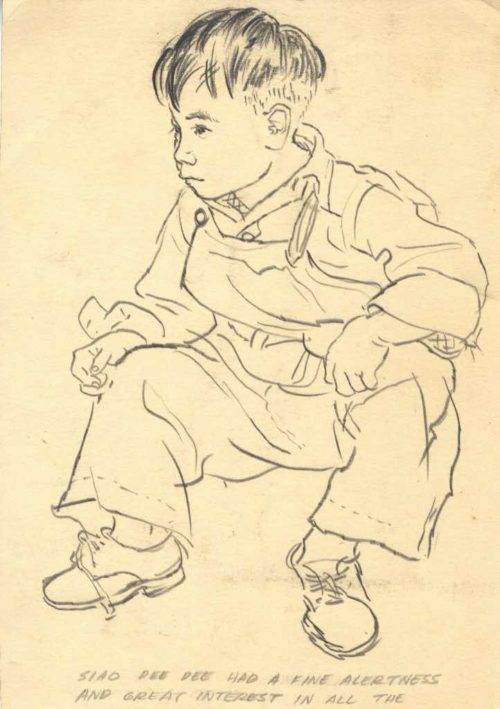

Smith made hundreds of drawings in Asia, filling sketchbook after sketchbook with images of the people and their customs and of children playing in the streets. He learned their language and made many friends.

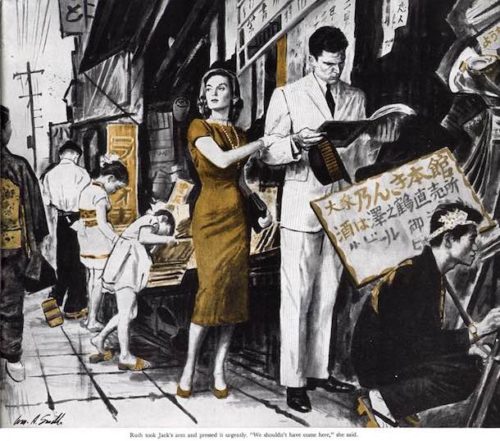

He grew to love the Far East and established lasting relationships with the artistic community there. He later traveled repeatedly to Japan and filled dozens of sketchbooks with drawings of Japanese culture. Unlike the harsh propaganda pictures he created during the war, his later drawings were exquisitely sensitive and appreciative of cultural differences.

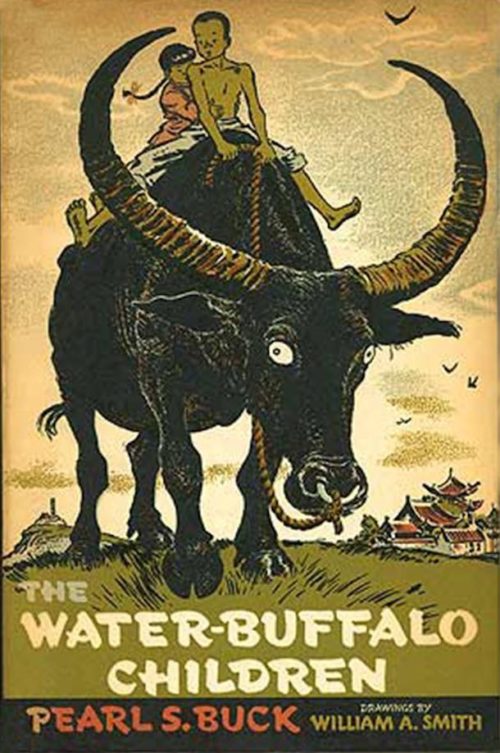

After the war, Smith went on to become a highly successful award-winning artist who worked regularly for the Post and other top publications of his day. He illustrated books for famous authors who wrote about the Far East, such as Pearl Buck and James Michener. His work was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Library of Congress.

Millions of readers of the Post saw his work, but most never knew that he earned his authenticity the hard way.

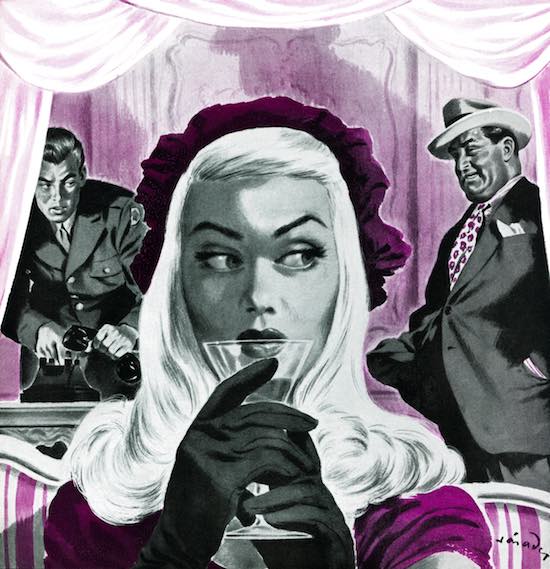

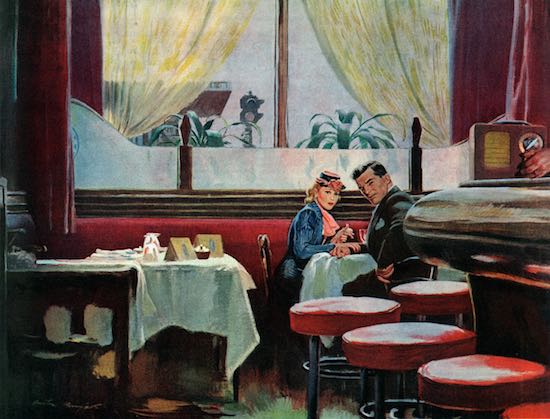

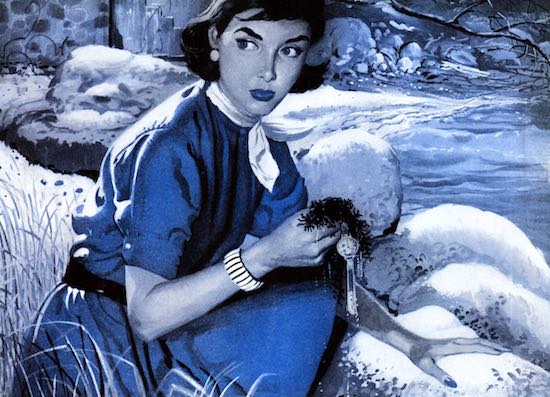

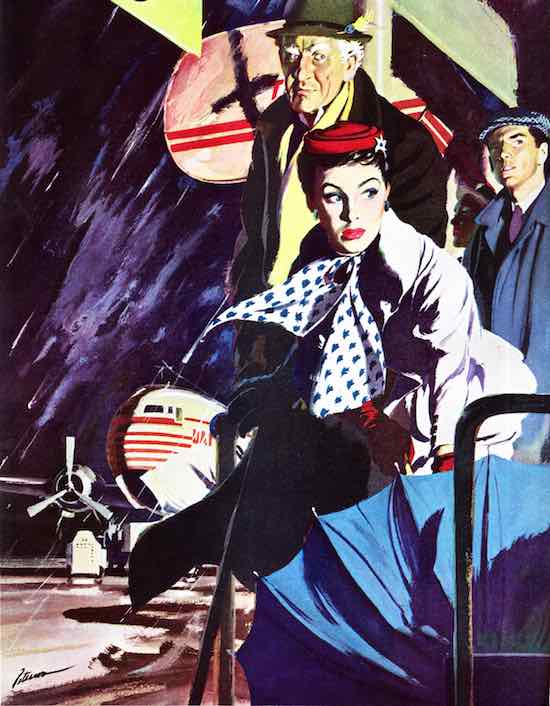

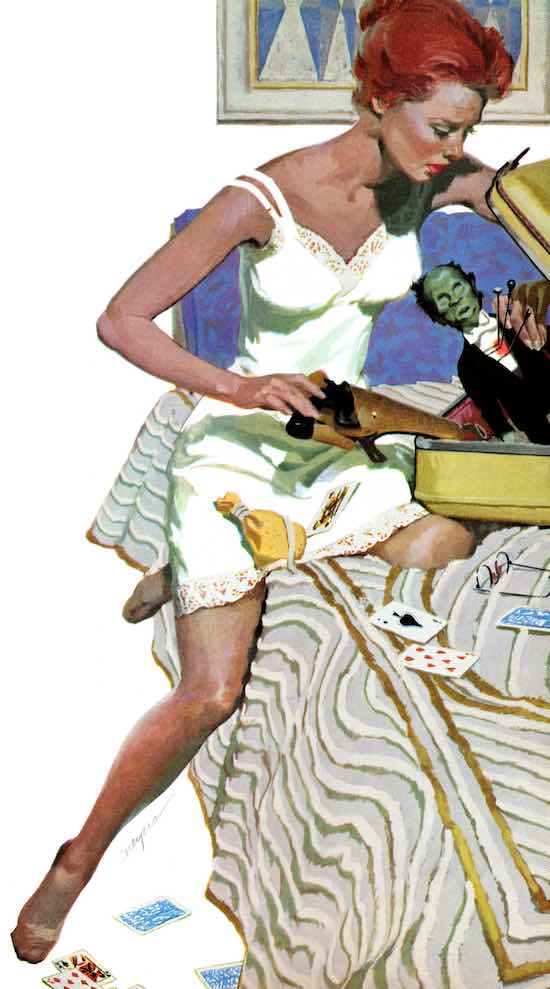

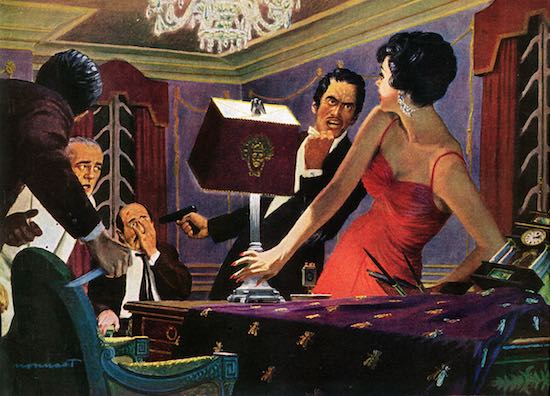

Gallery: Women of Mystery

Whether the women in these 1950s-era illustrations are solving crimes or committing them, you can be sure there’s plenty of intrigue afoot!

Which mystery-themed illustration do you like more? Let us know by responding with one of the designated emojis on our Facebook post! You’ll be entered into a random drawing for a chance to win a DVD set of Acorn TV‘s Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None.

In And Then There Were None, Ten strangers meet in a solitary mansion on a remote island near the Devon coast. Awaiting the arrival of their hosts, they start to die, one by one. Based on the best-selling book by Agatha Christie, this lavish adaptation features an all-star cast including Aidan Turner (Poldark), Charles Dance (Game of Thrones), Toby Stephens (Vexed), Anna Maxwell Smith (The Bletchley Circle), Miranda Richardson (The Hours), and Sam Neill (Peaky Blinders). Seen on Lifetime.

Deadline to vote is January 23. See Official Rules.

The Outcasts

Peter Stevens

September 29, 1956

Furlough in Flatbush

Frederic Varady

August 19, 1944

The Unsuspected

Austin Briggs

August 11, 1945

Sentence of Death

Ken Riley

October 23, 1948

Easy to Murder

James R. Bingham

January 6, 1951

Girls Are Where You Find Them

George Englert

January 17, 1953

Death in the Wind

Bernard D’Andrea

November 5, 1955

Rendezvous in Tokyo

William A. Smith

December 15, 1956

Murder on Order

Perry Peterson

March 9, 1957

The Artless Heiress

Robert Meyers

June 1, 1957

Gem Thief

November 29, 1958

It All Happened to Me

Austin Briggs

July 1, 1950

Feminine Reflex

George Englert

September 3, 1949