Considering History: Carter Woodson, Black History Month, and Reframing the American Story

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Although the first Black History Month was celebrated in February 1970, the original concept behind this commemoration of African American history and community is nearing its centennial anniversary. In 1926, pioneering African American educator, historian, and activist Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950) decided to designate the second week of February “Negro History Week.” That week features the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, and so provided a perfect occasion in which public schools—the central emphasis of Woodson’s idea—could remember those figures specifically and African American history more generally.

But Woodson did so much more than designate a special week. Many of Woodson’s own experiences, achievements, and ideas make him a figure worthy of commemoration, but one of his most critical contributions was his argument that African Americans were not peripheral to the American story but instead at the very heart of it. Woodson essentially attempted to completely reframe American history.

Ironically, a man so fully associated with education achieved his own educational milestones through a strikingly alternative path. Born to former slaves in Reconstruction-era Virginia, Woodson grew up in significant poverty and was unable to attend school for more than brief periods. After his family moved to West Virginia, he went to work as a coal miner at the age of 17, and was only able to enroll in Huntington’s Douglass High School (a segregated school named after Frederick Douglass) when he was 20 years old. But he graduated in two years, began teaching at a nearby school for the children of African American miners, and at the age of 25 was named Douglass High’s principal.

Woodson’s personal and professional links to education continued to develop from there in unconventional but groundbreaking ways. He took classes part-time at Kentucky’s Berea College while working at Douglass and received a BA in Literature in just three years. He then worked as a school supervisor in the Philippines for four years, returning to the United States (after a semester of study at the Sorbonne in Paris) to complete a second BA at the University of Chicago and then a PhD in History from Harvard (making him the second African American to receive a doctorate in history, after W.E.B. Du Bois). He would go on to work as a professor and dean at multiple historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), including Howard University and the West Virginia Collegiate Institute.

Those academic achievements—a doctorate and then faculty and administrative roles in higher education—might seem far removed from, if not opposed to, Woodson’s partial and haphazard educational first steps. But in his own lifelong arguments about African American education Woodson instead sought to link these disparate worlds, in two distinct ways: First, the realities of segregated education in America meant that African Americans could only achieve educational success through such haphazard opportunities, and Woodson argued that the highest levels of individual educational attainment could nonetheless stem directly from and build upon those opportunities. Second, educators and activists like Woodson worked in this era to create vital, collective resources for all African American students, families, and communities, from preparatory schools like Douglass to HBCUs like Howard, among many others.

Woodson’s experiences of community also inspired another of his most influential efforts and legacies. During his time in Chicago he stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA, a longstanding institution in the city’s historic African American Bronzeville neighborhood. It was that community, Woodson would later detail, that inspired him in 1915 to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, an organization devoted to better remembering and documenting such communities and their histories and stories. The Association (still in existence today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) published The Journal of Negro History and the Negro History Bulletin, worked with educators and schools around the country, and promoted the consistent and rigorous study of African American history both within and outside of the educational system.

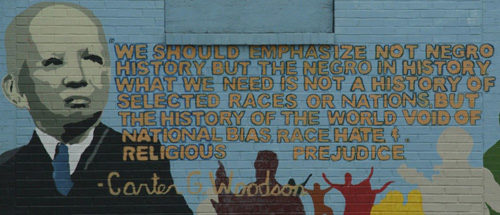

After founding the Association Woodson published his first two groundbreaking historical books, A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861 (1919). He would go on to write and publish many more books over the next few decades, works that spanned academic disciplines, educational debates, and public conversations. But perhaps even more important than the works themselves was Woodson’s radical reframing of what African American history meant and should mean for American community and identity. As he succinctly put it in describing the central goal of Negro History Week, “We should emphasize not Negro history, but the Negro in history.”

That might seem like a small or semantic difference, but I believe it instead reflects a profound revision and reframing. African American history, Woodson consistently argued, was not separate from nor peripheral to American history—it was instead at the heart of it, a crucial thread without which the larger fabric would not hold together (if it would still exist at all). That argument focused first and foremost on education, as Woodson noted that African Americans had for too long been “overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them.” But it was just as much a reframing of our collective memories, an effort to make African American history meaningful and vital for every American community and story.

There are many reasons we should feature Carter G. Woodson in our Black History Month commemorations this year, from his originating role and communal activisms to his inspiring individual story and achievements. But most of all he reminds us that Black history matters because it is American history.