The Great War: October 17, 1914

By this week 100 years ago, the war had stopped moving.

After just two months of fighting, the Western Front was locked in a stalemate. For the next four years, there would be no significant movement across a battle line that extended from neutral Switzerland to the coast of the North Sea.

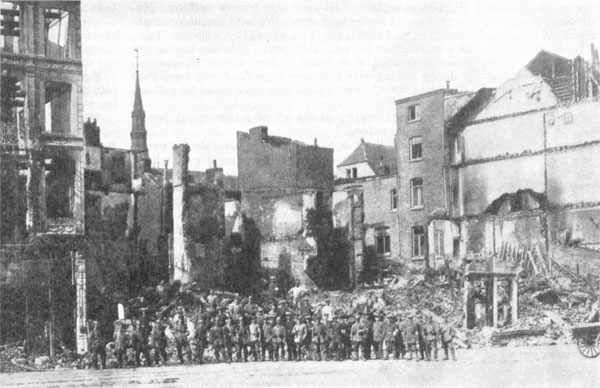

No one had expected this in 1914. Germany had launched its campaign with a bold assault across Belgium. For weeks they pushed back every Allied army in front of them — the Belgian, the French, and the English. The plan called for the German armies to sweep down into France, surround the remaining Allies, and capture Paris.

It might have worked, but a fresh French assault on the right side of the German line caused a split to form between the German armies. The French and British troops rushed into the gap. The German advance halted, then fell back to the Aisne River.

Both sides realized the way ahead was completely blocked, but there was still a chance to move around the enemy. The Germans began rushing to slip around the left side of the British army, while the British tried to slip around the right flank of the Germans. Both armies began racing north, trying to outflank each other. But they only succeeded in extending the battle line all the way across Belgium to the coast.

For the next four years, the Western Front would change very little. (The Eastern Front, between Russia and the Central Powers, would change quite a bit.) At no point would any army be able to shift the front lines more than a few miles, though both sacrificed thousands of men to break the enemy’s line.

Sherman Said It; Looking for War in a Taxicab — and Finding It

By Irvin S. Cobb

Irvin Cobb grabbed a taxicab in Brussels and said, in essence, “Follow that war.” When the driver would go no father, Cobb and his companions continued on foot into a small Belgian town.

“A minute later … we had gone perhaps 50 feet beyond the mouth of this alley when two men, one on horseback and one on a bicycle, rode slowly and sedately out of another alley, parallel to the first one, and swung about with their backs to us. I imagine we had watched the newcomers for probably 50 seconds before it dawned on any of us that they wore gray helmets and gray coats, and carried arms — and were Germans! Precisely at that moment they both turned so that they faced us; and the man on horseback lifted a carbine from a holster and half swung it in our direction.

“Realization came to us that here we were, pocketed. There were armed Belgians in an alley behind us and armed Germans in the street before us; and we were nicely in between. If shooting started the enemies might miss each other, but they could not very well miss us. Two of our party found a courtyard and ran through it. The third wedged himself in a recess in a wall behind a town pump; and I made for the half-open door of a shop.

“Just as I reached it a woman on the inside slammed it in my face and locked it.

“Then a troop of uhlans [cavalry] came, with nodding lances, following close behind the guns; and at sight of them a few men and women, clustered at the door of a little wine shop calling itself the Belgian Lion, began to hiss and mutter, for among these people, as we knew already, the uhlans had a hard name.

“At that a noncommissioned officer — a big, broad man with a neck like a bullock and a red, broad, menacing face — turned in his saddle and dropped the muzzle of his black automatic revolver on them. They sucked their hisses back down their frightened gullets so swiftly that the exertion well-nigh choked them, and shrank flat against the wall; and, for all the sound that came from them until he had holstered his gun and trotted on, they might have been dead men and women.”

Liberty—a Statement of the British Case

By Arnold Bennett

Most First World War historians avoid placing responsibility for the conflict with any one government. In fact, historians are now so careful not to ascribe guilt to any country, it seems the war was nobody’s idea. It just happened, apparently.

During the war, though, there was none of this hesitation. Everybody knew who started the war — “the other side.” Here, Englishman Arnold Bennett, author of 30 novels, states in no uncertain terms that Germany and Austria were to blame. What the Post didn’t know when it printed Bennett’s article, was that he was working for the British War Propaganda Bureau.

“The German military caste is thorough. On the one hand it organizes its transcendently efficient transport, if sends its armies into the field with both gravediggers and postmen, it breaks treaties, it spreads lies through the press, it lays floating mines, it levies indemnities, it forces foreign time to correspond to its own, and foreign news-papers to appear in the German language; and on the other hand it fires from the shelter of the white flag and the Red Cross flag, it kills wounded, even its own, and shoots its own drowning sailors in the water, it hides behind women and children, it tortures its captives, and when it gets really excited it destroys irreplaceable beauty. …

“If Germany triumphs, her ideal — the word is seldom off her lips — will envelop the earth, and every race will have to kneel and whimper to her: ‘Please may I exist?’ And slavery will be reborn; for under the German ideal every male citizen is a private soldier, and every private soldier is an abject slave — and the caste already owns 5 million of them. We have a silly, sentimental objection to being enslaved. We reckon liberty — the right of every individual to call his soul his own — as the most glorious end. It is for liberty we are fighting. We have lived in alarm, and liberty has been jeopardized too long.”

Hoping to make an ally out of the United States, Bennett was careful to mention a book that had recently surfaced, written by a member of the German army’s staff. In “Operations Upon the Sea”, Franz Frieherr von Edelsheim proposed an eventual assault on America.

“Von Edelsheim … begins by stating that Germany cannot meekly submit to ‘the attacks of the United States’ forever, and that she must ask herself how she can ‘impose her will.’ He proves that a combined action of army and navy will be required for this purpose, and that about four weeks after the commencement of hostilities German transports could begin to land large bodies of troops at different points simultaneously. Then, “by interrupting their communications, by destroying all buildings serving the state, commerce and defense, by taking away all material for war and transport, and lastly by levying heavy contributions, we should be able to inflict damage on the United States.” Thus in New York the new City Hall, the Metropolitan Museum and the Pennsylvania railway station, not to mention the Metropolitan Tower, would go the way of Louvain [a Belgian town where Germans burned, looted, and shot civilians], while New York business men would gather in Wall Street humbly to hand over the dollars amid the delightful strains of ‘The Watch on the Rhine.’ [A rousing German song from the 1850s, which asserted that the Rhine river must always remain German. It became an unofficial theme song for militant German nationalists during both world wars.]”

New Factors in War

By Samuel G. Blythe

In this report, Blythe observed several developing trends in the ancient art of war. Not only was the horse being replaced but soon airships would be bombing Paris and London. Even more ominous were the reports that France had developed a lethal gas for use on the battlefield. (The first poison gas attack on the Western Front was launched by the Germans in January 1915).

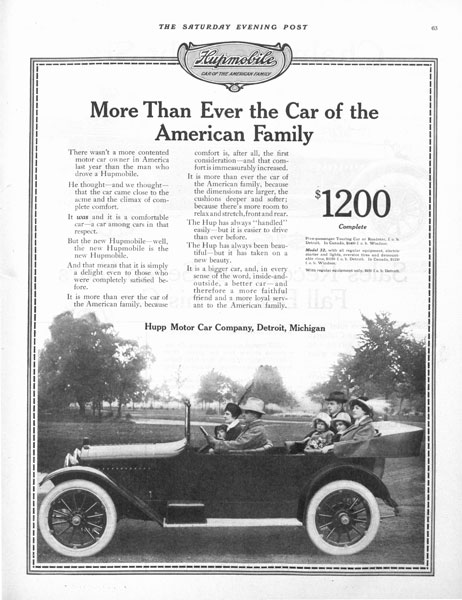

“It has been an axiom of war since wars began that an army travels on its belly. This war, which is the greatest of all wars, has made it necessary to revise that statement. As it now is, an army travels on its gasoline.

“Food, next to men, is the oldest factor in war, and gasoline is one of the newest. Of the two, gasoline—or petrol, as they call it over here — is the more important, because, as modern armies are organized and used, as well as from the sheer size of them, there would be little food for the soldiers if there were no gasoline.

“No staff officer goes anywhere on a horse. He uses an automobile. More than that, the Germans, and presumably the French, have taken auto delivery trucks of the heavier type and mounted field guns on them. These can be moved in any direction almost instantly. They constitute the most mobile artillery the world has ever known. In other wars artillery was shifted by horse or by hand. In this war some of the lighter guns are automobile guns, and they can be transferred from one point to another while horses are being brought up.

“I was told that a Frenchman had invented [a] identical gas that the imaginations of various novelists have invented for use in war fiction — a gas that is so frightful in its effect that when it is liberated all human beings and all living things within a large radius are instantly asphyxiated.

“I was told further that the French Government had the secret of the composition of this gas; that it had been proved out on sheep and cattle — that, at about the time I heard of it, a shell containing it was dropped two hundred feet from a flock of sheep, and that the sheep died instantly when the gas reached them.”

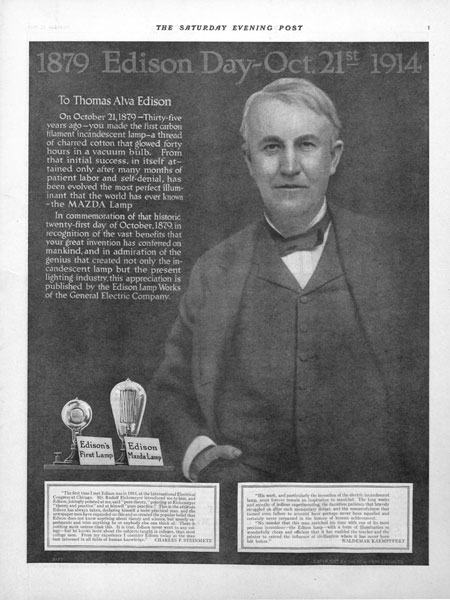

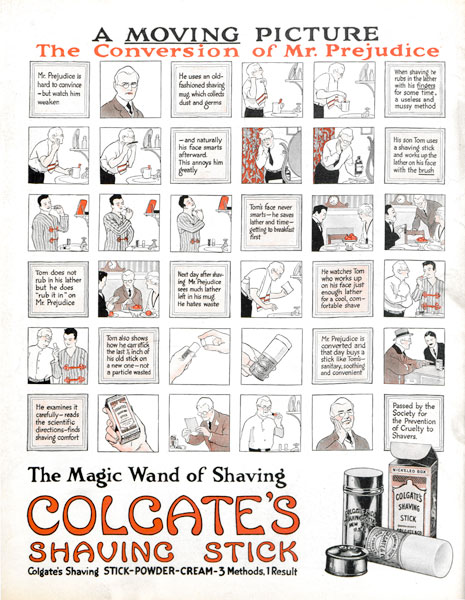

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 100 years ago.