What I Am Fighting For: My Home and Yours

In 1943, the Service Men’s Christian League held a writing contest asking the men of the armed forces what they were fighting for. This is one of four of their essays published in The Saturday Evening Post.

I’m fighting for that big white house with the bright green roof and the big front lawn, the house that I lived in before Hitler and the Japanese came into my life. I am fighting for those two big sycamore trees on the lawn where my brother and I spent so many happy and never-to-be-forgotten hours.

I am fighting for that little sister of mine, the one in the eighth grade, the one who shed so many tears when her brothers went marching off to war. I am fighting for those two gray-haired grown-ups who live in that house right now. Those two people who fought so hard to give those boys a good education, to keep them well clothed, well fed, and clean of body and mind.

I am fighting for that big stone church with its tall stained-glass windows, its big organ with the magnificent tone, its choir, its people who were always so glad to see us. I am fighting for that big brick schoolhouse, that fine old college with all its tradition and its ivy-covered walls, my room at home with all the books, that radio in the living room, that little black cocker spaniel with his big bright eyes and his funny walk.

I am fighting for that little sister of mine, the one in the eighth grade, the one who shed so many tears when her brothers went marching off to war.

I am fighting for my home and your home, my town and your town. I am fighting for New York and Chicago and Los Angeles and Greensboro and Hickory Flat and Junction City. And, above all, I am fighting for Washington. I am fighting for those two houses of Congress, for that dignified and magnificent Supreme Court, for that President who has led us so brilliantly through these trying years, and for the man who succeeds him.

I am fighting for everything that America stands for. I am fighting for the rights of the poor and the rights of the rich. I am fighting for the right of the American people to choose their own leaders, to live their own lives, to pursue their own careers, to save their money if they like or to spend their money if they like.

I am fighting for that freedom that so few of us seemed to realize we had before the war struck at us. I am fighting for that American belief in equality, in justice, and in an Almighty God.

We cannot lose.

—Sgt. Thomas N. Pappas, “What I Am Fighting For”, July 10, 1943

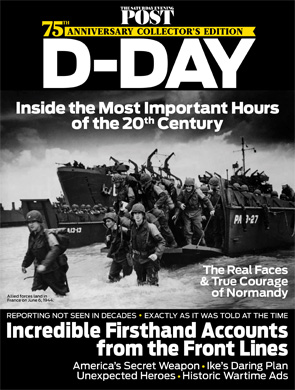

Excerpted from The Saturday Evening Post Collector’s Edition: D-Day. Now available in bookstores or online in our shop.

Excerpted from The Saturday Evening Post Collector’s Edition: D-Day. Now available in bookstores or online in our shop.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Norman Rockwell’s Freedom from Fear. (©SEPS)

This Is It! The Dawn of D-Day

All over the south of England, on the night of June 5, 1944, people awoke and went outside to listen. They had become used to noisy nights. The noise had changed through the past four years, from the distinctive beat of German bombers and the din of air raids, to the sound of British bombers outward bound at dusk and homeward bound at dawn. But people who heard the noise on the fifth of June remember it as different from anything that had ever been heard before. As they listened that night, with increasing excitement and pride, they knew that the greatest fleet of aircraft they had ever heard — the greatest fleet that anyone had ever heard — was passing overhead from north to south.

Some exclaimed, “This is it!” Many heard the sound with such deep emotion that they did not try to speak. It was the invasion, as everybody knew or guessed; and the invasion, if it succeeded, would redeem the defeat of Dunkirk and justify the British refusal to admit defeat. It would be a reward for the four years’ grinding labor by which they had dragged themselves up from the depths of 1940 to a state of national strength. And if it succeeded, it would mean the beginning of the end of the sorrow, boredom, pain, and frustration in which they had lived so long. People could not bring themselves to imagine what would happen if it failed. They went to sleep that night, if they slept at all, knowing the day would bring news of a battle which would influence all their lives forevermore.

The next morning, the main news in the papers and on the radio was still of the fall of Rome, which had been announced the day before. Nothing was said of events nearer home. But just after 9:00, the bare announcement came: “Under the command of General Eisenhower, Allied naval forces, supported by strong air forces, began landing Allied armies this morning on the coast of France.” Within a few minutes, this news was repeated all round the world.

[In the longer excerpt in our special publication D‑Day (see page 61), the author here details the months of concentrated planning and preparation invested in the Allied invasion of Normandy, codenamed Operation Overlord. With a fleet of 5,333 ships and 9,210 aircraft — the largest assembled anywhere — mobilized and in place, the success of the operation depended on an element no military commander could control: the weather.]

Absolutely everything was organized except the weather. For a landing on Monday, the fifth of June, some naval units had to sail on Friday the second. These included the heavy ships for the bombardment, which were starting from Scotland and Northern Ireland. The movement of men and materials out of the camps and into landing craft and transports also had to start on that day.

It would still be possible on the third to postpone everything for 24 hours, but by dawn on the fourth, the leading ships would have gone too far to be recalled. Weather, which was reasonably calm and clear, was regarded as absolutely essential for the landing.

All through May, the weather had given no reason for worry. But on June 1 it turned dull and gray, and on June 2 the meteorologists reported a complex system of three depressions approaching from the Atlantic. On June 3 they forecast high winds, low clouds, and bad visibility for the fifth, sixth, and seventh — the only three days when low tide was at the right time in the morning.

This forecast was presented at 9:30 p.m. on June 3 in Southwick House at a conference of Eisenhower, his deputy, his three commanders in chief, and their chiefs of staff. The first ships had sailed, tens of thousands of men were cooped up in landing craft and transports, and the camps they had left were being filled by follow-up troops; the whole immense machine was in motion. The problem at that moment was whether to let it go on or to stop it for 24 hours. Either way, the possibilities of disaster were clear.

At the meeting on Saturday evening, June 3, the report of the meteorologists and the advice of the commanders in chief made him almost certain that the operation would have to be postponed. It was an unwelcome prospect. Plans had been made by which everything could be brought to a standstill for 24 hours, but Eisenhower was sure that postponement would be hard on the morale and the physical condition of the troops already at sea. And any delay would add to the risk of the secret’s leaking out.

He decided to hold another meeting at 4:30 the next morning, Sunday, June 4, in the hope of some improvement in the forecast.

The next morning, the forecast was just as bad. At this meeting Adm. Ramsay doubted whether his smaller craft could cross the channel in the seas that were predicted. Air Chief Marshal Leigh-Mallory was certain the air forces would not be able to play their full part in the plan. By then, the main forces were due to sail in two hours’ time. Eisenhower gave the order to postpone the sailing for 24 hours and recall the ships at sea.

But the postponement had not solved Eisenhower’s problem. On Sunday evening, he faced the same terrible choice in an even more difficult form. The forecasters offered a chance, and only a chance, of a slight temporary improvement on Tuesday morning. The choice was therefore between launching the invasion on Tuesday, the sixth, in weather which was nothing better than a gamble, or postponing it for two weeks till the tides were right again. And so Eisenhower put off the final decision till early the following morning.

During that night he carried as heavy a burden as has fallen to the lot of any man. Everyone who had been at the evening meeting remembered one phrase he had used: “The question is, how long can you hang this operation out on a limb and let it hang there?” The troops could not stay in their ships for two weeks. But they had been briefed and told where they were to land. If all of them were brought ashore again, it was impossible to hope that the secret would not leak.

So far the German air force seemed to have spotted only a small proportion of the fleet and had never attacked it. That luck was too astonishing to last. In postponement for a fortnight, there were such risks of confusion, of loss of security, and of counterattack that the whole plan might have to be abandoned.

But the alternative of launching the invasion in uncertain weather was risky too. If the forecast was only slightly overoptimistic, landing craft would be swamped, naval and air bombardment would be inaccurate, German bombers might be able to take off while Allied fighters were grounded, and the invasion might end in the greatest military disaster which either the United States or Britain had ever suffered.

And finally, if the invasion failed, it would be impossible to try again that summer — perhaps impossible ever to try again. All the hopes and power of the United States and Britain had been put into this one attempt to bring the Germans to battle in Western Europe. If it failed, hope might also fail, not only in America and Britain but also in the countries which the Germans had occupied; the Russians might decide their allies were useless and make a separate peace. Eisenhower, with expert and dispassionate knowledge, knew that if the invasion failed, it might be impossible ever to win the war.

Reprinted from Dawn of D-Day by David Howarth by permission of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Story originally ran in The Saturday Evening Post March 14, 1959.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Inspiring words: Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower gives the order for the day: “Full victory — nothing else,” to paratroopers in England, just before they board their airplanes to participate in the first assault in the invasion of continental Europe. (U.S. Army)

Why D-Day Still Matters

Acclaimed historian John McManus began his book The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach with these words: “Desperate. Hellish. Disastrous. Catastrophic. Traumatic. Shocking. Bloody. Anyone who was at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944 … is likely to have used one or more of those powerful words to describe it. At Omaha Beach, the stakes were so high, and the fighting so bitter, that the very name involves something legendary, even iconic.”

McManus reminds us that continuing to explore the events around that invasion reveals much about what has shaped our role in wars to come. With the help of years of research and personal interviews with those who fought, the author shares his thoughts with the Post’s West Coast editor.

Jeanne Wolf: As the war in Europe raged on, our country was strongly isolationist. Was D-Day, at least symbolically, a watershed moment where we began our commitment to becoming a leader of Western Europe and the free world?

John McManus: It was really one of the key moments for America in World War II as it ended our determination not to get deeply involved. I really think that a great realization happened after the fall of France in 1940. It was stunning. I think that most Americans felt that at that point, “Well we don’t want to be in the war formally just yet, but we better get ready.”

This soon led to a shift in outlooks, a shift in values and perspective toward more of an American involvement in Europe, and more internationalism. And D-Day was the logical outgrowth of such thinking.

JW: It’s not too much to say that one day made such a momentous change?

JM: No. What’s so compelling about the Normandy invasion is that there aren’t that many actual single dates in history like that which you could look at and say, “Wow, this is a day that you know that sets the tone for decades.” D-Day was definitely one of those days. I mean there was so much on the line if the invasion failed. For America, it was kind of an emblematic commitment because D-Day was the first day of almost a year of very heavy fighting. From that day forward, the campaign to defeat Nazi Germany would be about two-thirds American in terms of manpower and especially material power. There was an enormous blood-cost.

JW: In planning the D-Day invasion, Eisenhower was named the leader. Why was an American in charge of a war that had already been going on for five years? And did this foreshadow our leadership role in Europe?

JM: There was no doubt that an American would be in charge of Operation Overlord because only one country out of the Western coalition could lead this invasion and, more importantly, the campaign that followed. If we pull the lens back further from an American point of view, D-Day was just one of our massive operations going on globally at that point. There were huge operations in the Pacific and the bombing campaign of Germany. All of this stuff was happening, so it was like, “Wow, look what America is capable of.” We had become a military and economic superpower. That’s why the Normandy invasion was not possible until 1944, because among the Western countries, only the United States really had the kind of power to lead the invasion and the subsequent campaign. What you’re seeing there is the beginnings of NATO. I think there was no question there would be an American commander.

What the American people always have to ask themselves is: “Is this worth it?” It is a very serious question.

JW: There’s a lot of talk today about “wasting money” on military support of other countries and, more specifically, the cost/benefit of supporting NATO and whether we’re paying too much or whether others aren’t paying their fair share. But some argue that the benefit of allying with Europe, even at great cost, is priceless.

JM: A hundred and ten thousand Americans died in World War I. World War II was even bloodier. Then we went through a decades-long commitment to protecting Europe through the emblem of NATO during the Cold War and even beyond. There’s bound to be some weariness and bound to be waste, and when we have so many social problems in this country, a lot of people are quite rightly thinking, Well, shouldn’t we be worried about those too? But the world is a small place. What happens in Europe tends to really matter for us too, and that hasn’t changed. So the Americans have been going round and round with their NATO allies for decades about whether we’re carrying too much of the cost and the responsibility. It’s not a new issue.

JW: Because not helping can be so disastrous?

JM: Just think, what if Europe became a key part of the world that was hostile to the United States and its values. What would that mean for the hundreds of thousands of lives that the U.S. expended to make sure Europe was free in World War II and the millions, yes millions, of lives that were affected by the Cold War. It is a question of whether America really represents freedom internationally or if it’s not as important to us.

JW: Aren’t we the world’s police force, in a sense, protecting civilization every day?

JM: Whether you like it or not, there’s a lot of truth in that. And whether you’re a soldier or not doesn’t matter because the American people are ultimately paying for a lot of this in so many ways. So yeah, it affects you whether you know it or not, and that’s part of what I tell all my students. It’s certainly in your interest to know more and understand more because you’re affected by this.

JW: The debate goes on. Is our engagement — in World War II, Korea, Vietnam, even Iraq — is it on moral grounds? Or is it self-interest?

JM: I think the answer is “yes” and “yes.” It’s both. You had that even after World War I. The American government told us we were fighting to save the world for democracy, and actually what we saw was that there was a lot of hardcore economic value there, too. Well, welcome to American conflict around the world, because it’s the same thing as it was in World War II and the Cold War. It’s the same thing in Iraq or the Korean War or wherever it might be. But one theme you do see as a historian in a lot of these places is that when the Americans go, and they’re willing to stay in for the long haul, you tend to see a kind of better country come out of that. I’m alluding obviously to Germany, Japan, Korea — you do tend to see this. Or, when the Americans leave — Vietnam would be a really good example of another kind of outcome. So what the American people always have to ask themselves is: “Is this worth it?” It is a very serious question. I would never say otherwise. D-Day is just one example of that. There’s always a tremendous blood investment. The title of my book comes from Colonel George Taylor, who was commanding the lead assault at Normandy and said to his men, “Only two kinds of people are going to be on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die. Now get moving.”

JW: We hear all the time that those who fought the battle of D-Day were members of what has been called the “greatest generation” — men willing to stand up and sacrifice for the greater good. How do you explain that spirit?

JM: There was definitely an understanding of how crucial D-Day was and that it had to succeed. But I think what really caused them to go on is a kind of a camaraderie. All the higher-minded patriotic stuff that they may feel after you get through about 80 layers of cynicism is not why people really fight. They fight because of the guys next to them. I talked to survivors who explained that they thought in the midst of the chaos, I know a lot of people are relying on me. I’ve got to do my part. And that kept many of them continuing to risk their lives.

JW: In the end, wasn’t it easier to fight that battle on Omaha Beach and the war because we had the moral clarity of being on the right side?

JM: World War II is unique in that it is a mass participation war, though, believe it or not, two-thirds of those who served were draftees and only one-third volunteers. Still, it was a popular war. And that’s very rare in American history. Most of our wars have either been or become incredibly unpopular with some Americans. But World War II was a linear war; you could look toward a concrete series of steps that would lead you to victory. It was a war that was waged against nation-state actors whom you could identify and fight — and fight to victory. And it’s one of the rare times in American history where both parties came together on this idea — well, let’s work together toward the victory.

John McManus’ newest book is Fire and Fortitude: The U.S. Army in the Pacific War, 1941-1943, July 30, 2019.

This article is featured in the May/June 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: U.S. Army

From the Front Lines of World War II: 15 Minutes Over Paris

There are countless stories of heroism and victories in the Second World War that we’ll never know. They passed into time without being given proper attention.

Fortunately, The Saturday Evening Post reported some of these incidents, sometimes written by the men and women who lived through them.

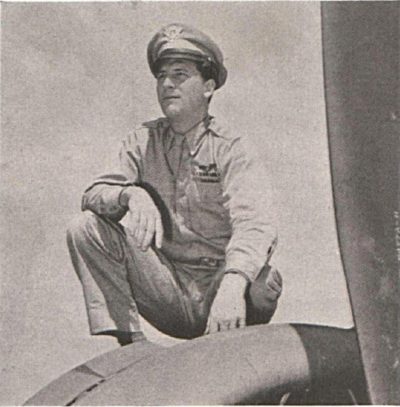

One of the most memorable was published 75 years ago: “Fifteen Minutes Over Paris.” Major Allen Martini’s account of how he and his B-17 crew survived a bombing run reads more like a Hollywood version of an air battle.

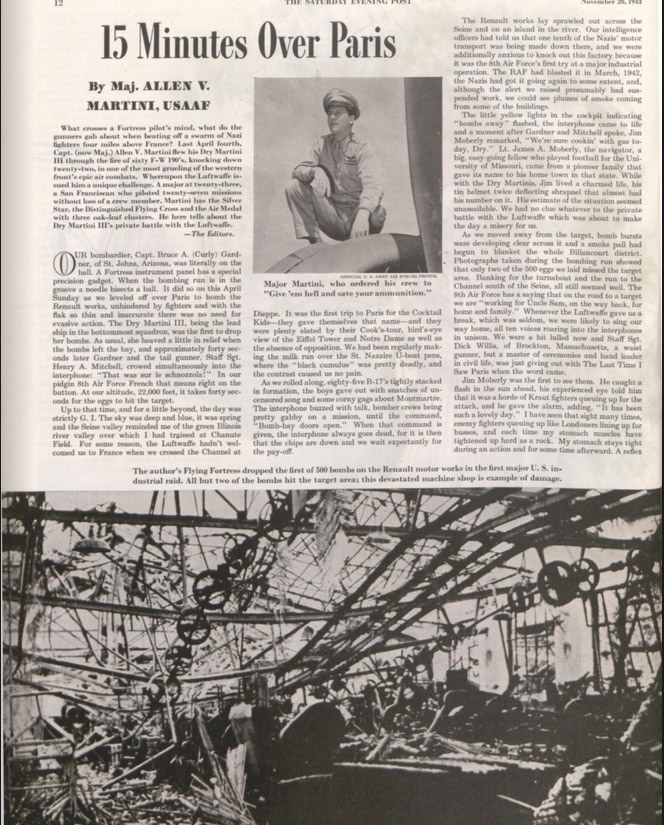

The story begins on April 4, 1943, when the 8th Air Force took off on its first attack on a major industrial target. Among the formation was the Flying Fortress named “Dry Martini.”

The sky that April morning was blue and empty of threats. On the way to the target, which was a Renault factory outside Paris, the antiaircraft fire had been so light that Major Martini didn’t even need to take evasive action. Once its bombs were dropped, the Dry Martini banked and headed back to England as the entire crew happily sang “The Last Time I Saw Paris.”

Then, in the sky above, over a dozen German fighter planes materialized. Martini watched, fascinated, as they methodically lined up for attack. Suddenly, they pounced on the squadron. Three of the American bombers were shot down. One engine of The Dry Martini was damaged. The fighter planes had also shot out the cockpit’s windshield. One crew member was killed instantly and a piece of the windshield struck Martini’s co-pilot, knocking him senseless and leaving Martini alone at the controls with a thirty-below-zero wind blasting into his face.

And then the real trouble began.

For the next fifteen minutes the Dry Martini flew through an inferno of cannon and machine gun fire, the sole target of 60 German planes. “Fifteen Minutes Over Paris” is his account of what the crew went through in that long quarter hour.

Martini and his crew pressed on, fighting desperately. By the time they reached Rouen, near the Normandy coast, six of the bomber’s guns were out of commission, burned out from constant firing. The functional guns were down to the last 12 rounds of ammunition.

Suddenly a new squad of fighters was seen approaching. Martini ordered his men to hold their fire until he knew they were enemy planes. Instead, to the crew’s great relief, it was a squadron of Spitfires racing in to help them. The Germans, seeing the dreaded Spitfires, quickly peeled away to fly back to their base.

The planes had taken an incredible amount of punishment. The wings and fuselage had been ripped up by 160 cannon and bullet holes. Yet the “Cocktail Kids” as the crew deemed themselves, gave even better than they got. They took 22 enemy airships out of action that day, the largest score ever run up by a single bomber.

Major Martini went on to complete 27 missions, two more than needed to earn his return home. Back in the states, he appeared in war-bond rallies and wrote an account of that famous flight, which appeared in the Post.

“Fifteen Minutes Over Paris” is a fascinating account of the courage and determination of ten men that deserves to be better known.

Featured image: from The Saturday Evening Post, November 20, 1943, page 13. Courtesy American Air Museum via Creative Commons by CC-by-NC license.