Did We Mortgage Our Identity? The 1960s Worries About Conformity

By the 1950s, it was clear the 20th century wasn’t going to be the era of peace and prosperity Americans had predicted in 1900. It had brought them a world war, a major depression, and another world war, and now an interminable cold war. Americans were getting tired of the constant belt-tightening and war preparedness; they wanted to enjoy the society they’d built. But many were disappointed with the society they found. There was a general sense that things could, and should, be better.

Even if Americans didn’t feel a troubling malaise, the media certainly made a case for it. Journalists continually wrote of problems in American society, such as racism, alienation, and materialism. They also referred to the problem of “conformity.”

There was no single definition of the term. Popular magazines and television talked of conformity as the desire to fit in: Americans, like their milk, were becoming homogenized. They were abandoning their individual differences to fit in and get ahead. A popular song of 1962, “Little Boxes,” talked of people, their lives, and their “ticky tacky” houses all looking the same. But conformity was more than just the desire to accommodate the mainstream of America.

Between 1959 and 1963, three authors, each highly regarded for his insight and judgment, weighed in on the subject.

Erich Fromm, the renowned psychologist and philosopher, wrote “Our Way Of Life Is Making Us Miserable” in 1964. The need to conform, he said, didn’t arise in Americans but in their organizations, which rewarded people…

who cooperate smoothly in large groups, who want to consume more and more, and whose tastes are standardized and can be easily influenced and anticipated. It needs men who feel free and independent, yet who arc willing to be commanded, to do what is expected to fit into the social machine without friction; men who can be guided without force, led without leaders, prompted without an aim except the aim to be on the move, to function, to go ahead.

Our society is becoming one of giant enterprises directed by a bureaucracy in which man becomes a small, well-oiled cog in the machinery. The oiling is done with higher wages, fringe benefits, well-ventilated factories and piped music, and by psychologists and “human-relations” experts; yet all this oiling does not alter the fact that man has become powerless, that he does not wholeheartedly participate in his work and that he is bored with it.

[We should give Fromm credit for recognizing his profession might be enabling the system by helping citizens endure an unfriendly system.]

The ‘organization man’ may be well fed, well amused and well oiled, yet he lacks a sense of identity because none of his feelings or his thoughts originates within himself; none is authentic. He has no convictions, either in politics, religion, philosophy or in love. He is attracted by the “latest model” in thought, art and style, and lives under the illusion that the thoughts and feelings which he has acquired by listening to the media of mass communication are his own.

He has a nostalgic longing for a life of individualism, initiative and justice, a longing that he satisfies by [watching cowboy movies.] But these values have disappeared from real life in the world of giant corporations, giant state and military bureaucracies and giant labor unions.

He, the individual, feels so small before these giants that he sees only one way to escape the sense of utter insignificance: He identifies himself with the giants and idolizes them as the true representatives of his own human powers, those of which he has dispossessed himself.

Such ideas aren’t particularly surprising, coming from a humanist and psychologist. But much of what he says was echoed by other Post contributors in the early 1960s, including a social critic from an unexpected quarter.

Private Wilburn Kirby Ross: An American Hero

Andrew Stillman Phipps provided us this account of the incredible courage that earned Wilburn Ross the Medal of Honor.

It is an extremely hard medal to earn; more than half of the men who earned the Medal of Honor died in their achievement.

Since 1862, when it was first given to members of our armed forces for gallantry and bravery beyond the call of duty, it has been awarded 3,445 times.

During the First World War, the President, acting on behalf of Congress, awarded the Medal to 124 servicemen. During World War II, it was awarded 464 times. All of the World War I recipients are now gone, and only 32 remain of World War II’s recipients. One of these is Wilburn Kirby Ross. “Wib”, as he is affectionately known by family and friends, is now 86 years of age and still reflects the modesty known to most heroes as only doing their duty.

He was born on May 12, 1922, in McCreary County, Kentucky, about 30 miles north of Pall Mall, Tennessee, the home of Sgt. Alvin York. Just four years before Ross was born, York won the Medal of Honor for leading an attack on a German machine-gun nest in France. Commanding seven other men, York captured 32 machine guns, killed 28 German soldiers, and forced the surrender of 132 other Germans.

Ross would have grown up hearing about Sergeant York’s accomplishments again and again; it was an area with few opportunities for distinguishing yourself. Most people made their living cutting timber, coal mining, and subsistence farming. At best, life was hard and most people were poor. Opportunities for education and good jobs were almost non-existent. Faith, family, and freedom were, and are, important to these people whose background was forged by generations of hardy pioneers.

On October 30, 1944, another representative from this region achieved recognition. Wilburn Ross, serving as a private with the 350th Infantry, manned a machine gun to drive back six attacks by German troops. He held his position even after the riflemen supporting him ran out of ammunition. He continued firing even as enemy soldiers were lobbing grenades at him from just 4 yards away. He refused to withdraw when he ran out of ammunition. Instead, he held his position as the German prepared for another attack. The ammunition arrived at the last minute, enabling him to repulse the German assault. All tolled, Ross held his position under intense fire for 36 hours.

Asked about his heroism, “Wib” has said, “I had been in this so long, I knew what they (the Germans) were doing. When they would charge, I would mow them down.”

While serving on the Italian front, Ross was captured at the Anzio beachhead, but miraculously escaped. Dusk was coming and, for some reason, the enemy guard did not appear to be paying much attention to him, instead fixing their attention on his buddies and talking to them. Ross moved out of sight and commenced to walk away. It was night now, and those moving about him were not able to see that he was an American.

He eluded further capture and survived on his own for three days and four nights. He says, “I didn’t get hungry. I didn’t get thirsty. I was worried about getting out of there.” Traveling at night, he hid under leaves during the day. Once the Germans got so close to him, he said, “I could have reached out my hand and touched the man on his coat.”

Later, seeing American planes in the sky, he followed the direction of their flight and was happy to reunite with American forces, where he gratefully dug into a can of meat and beans.

When Ross returned to Strunk, Kentucky, he was greeted by a crowd of 3,000 citizens, Governor Simeon Willis, and a neighbor who could best appreciate Ross’s bravery and dedication: Sergeant Alvin C. York.

Americans should be grateful that uncommon valor has commonly appeared among the men and women in our armed forces. They have served their country beyond the ability of our small tributes to repay them. We must never forget those who have stood in harm’s way to defend liberty and to pay the continually rising price of freedom.

Classic Covers: World War I

As we all know, we have too many wars to remember. Last month on this website, we ran a story on a Post newsboy who was killed in World War I. Seeing the photos from the article inspired me to show some World War I covers from both The Saturday Evening Post and Country Gentleman, a longtime sister publication. Some are well known, but I’ve discovered a few surprises. All are intended as a tribute to our veterans of today and yesterday.

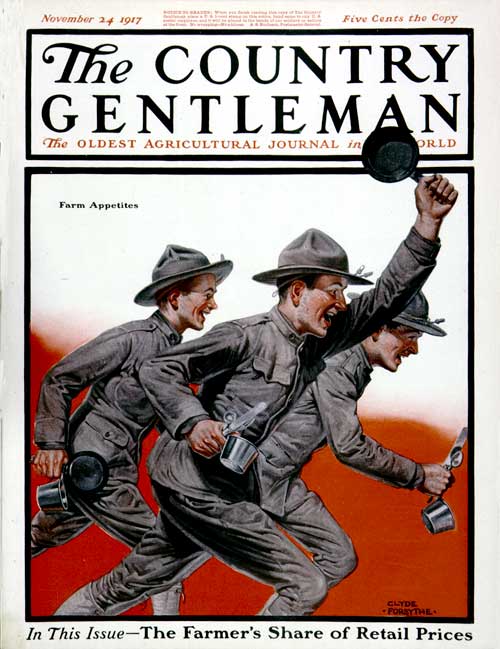

Farm Appetites – Clyde Forsythe – November 24, 1917

We have plenty of poignant wartime covers, but this one is fun! These are hearty farm-boys-turned-soldiers, and the painting is appropriately named: “Farm Appetites.” It was done by cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, a friend of Norman Rockwell. In fact, it was Forsythe who encouraged the reticent, nervous young Rockwell to try to sell a cover to the venerable Saturday Evening Post. So Forsythe not only painted history, he helped to make it.

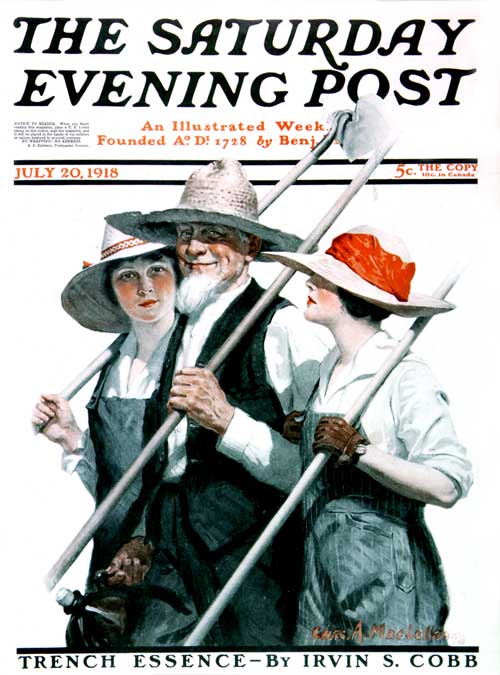

Women Work for War – Charles A. MacLellan – July 20, 1918

Charles A. MacLellan

September 8, 1917

And who, pray, worked the land while the male farm hands were fighting the war? The “women’s land army”, that’s who. Some were country girls, others were out of their element working farms, but the women of the U.S. and Europe wanted to do their part back home.

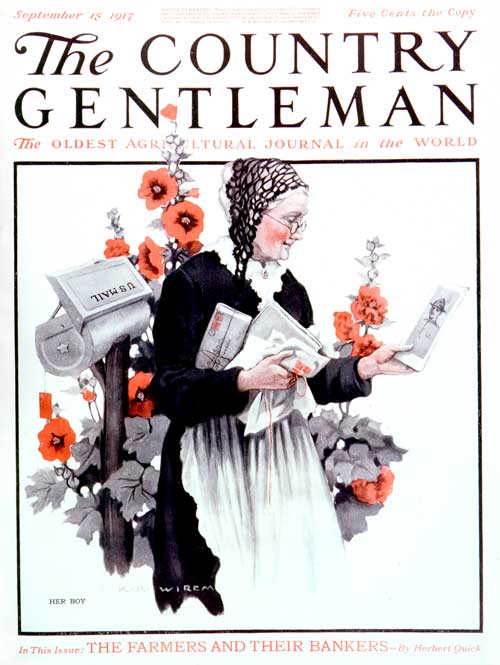

Her Boy – K.R. Wireman” – September 15, 1917

Another seldom-seen Country Gentleman cover shows a proud mother at the mailbox, receiving a photo of her son in uniform. Let’s hope he’s back at the farm soon. This was by artist K.R. Wireman.

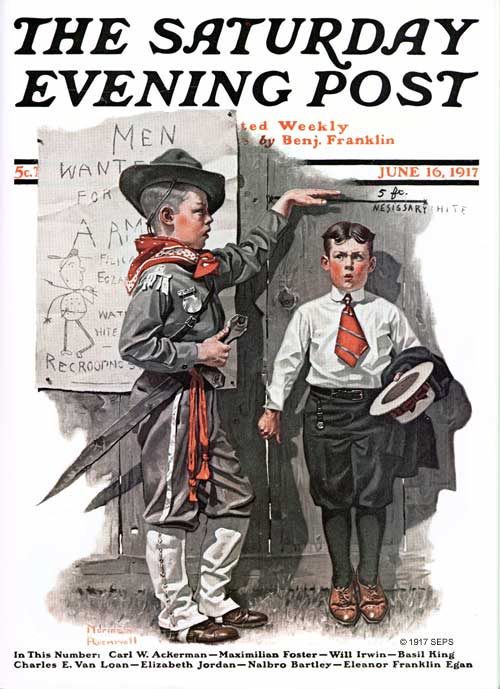

Necessary Height – Norman Rockwell – June 16, 1917

Back at The Saturday Evening Post, a gent we all know and love, Norman Rockwell, was also recognizing the war in his art. Only about 22 himself at the time, Rockwell shows us that even the youngsters were getting into the war effort. Playing recruiter, a boy (notice the “recruiting poster”) seems to be questioning the qualifications of a vertically challenged applicant.

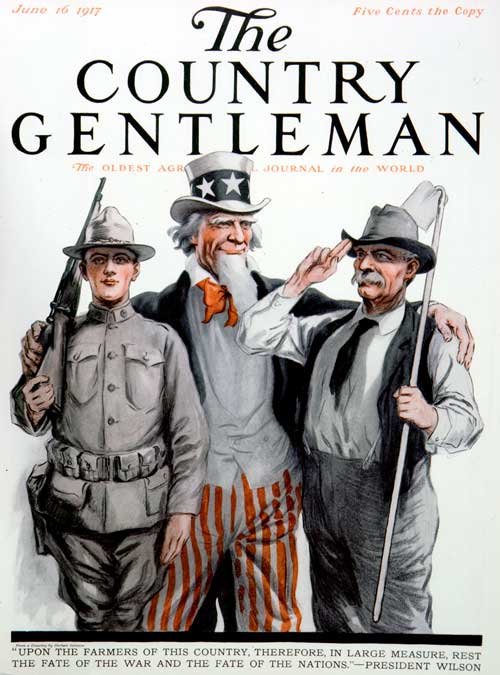

Uncle Sam – Herbert Johnson – June 16, 1917

This trio was vitally important to the nation in World War I. The American soldier, good old Uncle Sam and the American farmer. This was from a painting by Herbert Johnson, a well-known political cartoonist for both the Post and Country Gentleman.

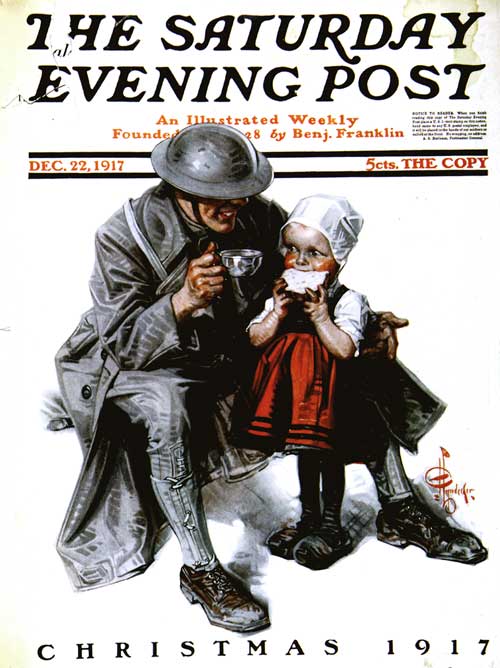

Soldier’s Christmas – J.C. Leyendecker – December 22, 1917

I can’t leave without sharing my favorite World War I cover, “Soldier’s Christmas” by J.C. Leyendecker. A soldier is sharing his meager holiday meal with a tiny French girl. Can’t help it – gets me every time.