“The Eyes of Asia: The Fumes of the Heart” by Rudyard Kipling

Although he was widely regarded as one of the most famous British authors of all time, Rudyard Kipling’s birthplace was across the world from the British Isle in what was then known as British India. Kipling drew upon his upbringing in Bombay as inspiration for many of his most famous works including The Jungle Book (1894) and Kim (1901). The first English-speaker to win the Nobel Prize in Literature harkened back to his childhood in his novel The Eyes of Asia, about a Sikh Man’s experience fighting in World War I for the British.

Published on May 19, 1917

SCENE: Pavilion and Dome Hospital, Brighton — 1915. What talk is this, Doctor Sahib? This Sahib says he will be my letter writer? Just as though he were a bazar letter writer? … What are the Sahib’s charges? Two annas? Too much; I give one. . . . No! No! Sahib! You shouldn’t have come down so quickly. You’ve forgotten; we Sikhs always bargain … Well, one anna be it. I will give a bond to pay it out of my wound-pension when I get home. Sit by the side of my bed …

This is the trouble, Sahib: My brother, who holds his land and works mine outside Amritsar City, is a fool. He is older than I. He has done his service and got one wound out of it in what they used to call war — that child’s play in the Tirah. He thinks himself a soldier! But that is not his offense. He sends me post cards, Sahib — scores of post cards — whining about the drouth, or the taxes, or the crops, or our servants’ pilferings, or some such trouble. He doesn’t know what trouble means. I want to tell him he is a fool … What? True! True, one can get money and land, but never a new brother. But for all that, he is a fool … Is he a good farmer? Sa-heeb! If an Amritsar Sikh isn’t a good farmer a hen doesn’t know an egg … Is he honest? As my own pet yoke of bullocks. He is only a fool. My belly is on fire now with knowledge I never had before, and I wish to impart it to him — to the village elders — to all people. Yes, that is true too. If I keep calling him a fool he will not gain any knowledge … Let me think it over on all sides. Aha! Now that I have a bazar writer of my own, I will write a book — a very book to my fool of a brother … And now we will begin. Take down my words from my lips to my foolish old farmer brother:

“You will have received the notification of my wounds which I took in Franceville. Now that I am better of my wounds, I have leisure to write with a long hand. Here we have paper and ink at command. Thus it is easy to let off the fumes of our hearts. Send me all the news of all the crops and what is being done in our village. This poor parrot is always thinking of Kashmir.

“As to my own concerns, the trench in which I sat was broken by a bomb-golee as large as our smallest grain chest.” [He’ll go off and measure it at once!] “It dropped out of the air. It burst, the ground was opened and replaced upon seven of us. I and two others took wounds. Sweetmeats are not distributed in wartime. God permitted my soul to live, by means of the doctors’ strong medicines. I have inhabited six hospitals before I came here to England. This hospital is like a temple. It is set in a garden beside the sea. We lie on iron cots beneath a dome of gold and colors and glittering glasswork, with pillars.” [You know that’s true, Sahib. We can see it — but d’you think he’ll believe? Never! Never!] “Our food is cooked for us according to our creeds — Sikh, or Brahmin, or Mussulman, and all the rest. When a man dies he is also buried according to his creed. Though he has been a groom or a sweeper, he is buried like some great landowner. Do not let such matters trouble you henceforth. Living or dying, all is done in accordance with the ordinance of our faiths. Some low-caste men, such as sweepers, counting upon the ignorance of the doctors, make a claim to be of reputable caste in order that they may get consideration. If a sweeper in this hospital says he is forbidden by his caste to do certain things he is believed. He is not beaten.” [Now, why is that, Sahib? They ought to be beaten for pretending to caste, and making a mock of the doctors. I should slipper them publicly — but — I’m not the Government. We will go on.]

“The English do not despise any sort of work. They are of many castes, but they are all one kind in this. On account of my wounds I have not yet gone abroad to see English fields or towns.” [It is true I have been out twice in a motor carriage, Sahib, but that goes too quickly for a man to see shops, let alone faces. We will not tell him that. He does not like motor cars.] “The French in Franceville work continually without rest. The French and the Phlahamahnds-Flamands — who are a caste of French, are kings among cultivators. As to cultivation” — [Now, I pray, Sahib, write quickly for I am as full of this matter as a buffalo of water] — “their fields are larger than ours, without any divisions, and they do not waste anything except the width of the footpath. The land descends securely from father to son upon payment of tax to the Government, just as in civilized countries. I have observed that they have their land always at their hearts and in their mouths, just as in civilized countries. They do not grow more than one crop a year, but this is recompensed to them because their fields do not need irrigation. The rain in Franceville is always sure and abundant and in excess. They grow all that we grow, such as peas, onions, garlic, spinach, beans, cabbages and wheat. They do not grow small grains or millet, and their only spice is mustard. They do not drink water, but the juice of apples, which they squeeze into barrels for that purpose. A full bottle is sold for two pice. They do not drink milk, but there is abundance of it. It is all cows’ milk, of which they make butter in a churn, which is turned by a dog.” [Now, how shall we make my brother believe that? Write it large.] “In Franceville the dogs are both courteous and industrious. They play with the cat, they tend the sheep, they churn the butter, they draw a cart and guard it too. When a regiment meets a flock the dogs of their own wisdom order the sheep to step to one side of the road. I have often seen this.” [Not one word of this will he or anyone in the villages believe, Sahib. What can you expect? They have never even seen Lahore City! We will tell him what he can understand.] “Plows and carts are drawn by horses. Oxen are not used for these purposes in these villages. The fieldwork is wholly done by old men and women and children, who can all read and write. The young men are all at the war. The war comes also to the people in the villages, but they do not regard the war because they are cultivators. I have a friend among the French — an old man in the village where the Regiment was established, who daily fills in the holes made in his fields by the enemy’s shells with dirt from a long-handled spade. I begged him once to desist when we were together on this work, but he said that idleness would cause him double work for the day following. His grandchild, a very small maiden, grazed a cow behind a wood where the shells fell, and was killed in that manner. Our Regiment was told the news and they took an account of it, for she was often among them, begging buttons from their uniforms. She was small and full of laughter, and she had, learned a little of our tongue.” [Yes. That was a very great shame, Sahib. She was the child of us all. We exacted a payment, but she was slain — slain like a calf for no fault. A black shame! . . . We will write about other matters.]

“As to cultivation, there are no words for its excellence or for the industry of the cultivators. They esteem manure most highly. They have no need to burn cow dung for fuel. There is abundance of charcoal. Thus, not irrigating or burning dung for fuel, their wealth increases of itself. They build their houses from ancient times round about mountainous dung heaps, upon which they throw all things in season. It is a possession from father to son, and increase comes forth. Owing to the number of army horses in certain places there arises very much horse dung. When it is excessive the officers cause a little straw to be lit near the heaps. The French and the Phlahamahnds, seeing the smoke, assemble with carts, crying: ‘What waste is this?’ The officers reply: ‘None will carry away this dung. Therefore, we burn it.’ All the cultivators then entreat for leave to carry it away in their carts, be it only as much as two dogs can draw. By this device horse lines are cleaned.

“Listen to one little thing: The women and the girls cultivate as well as the men in all respects.” [That is a true tale, Sahib. We know — but my brother knows nothing except the road to market.] “They plow with two and four horses as great as hills. The women of Franceville also keep the accounts and the bills. They make one price for everything. No second price is to be obtained by any talking. They cannot be cheated over the value of one grain. Yet of their own will they are generous beyond belief. When we came back from our work in the trenches they arise at any hour and make us warm drinks of hot coffee and milk and bread and butter. May God reward these ladies a thousand times for their kindness! But do not throw everything upon God. I desire you will get me in Amritsar City a carpet, at the shop of Davee Sahai and Chumba Mall — one yard in width and one yard and a half in length, of good color and quality to the value of forty rupees. The shop must send it with all charges paid, to the address which I have had written in English character on the edge of this paper. She is the lady of the house in which I was billeted in a village for three months. Though she was advanced in years and belonged to a high family, yet in the whole of those three months I never saw this old lady sit idle. Her three sons had gone to the war. One had been killed; one was in hospital; and a third, at that time, was in the trenches. She did not weep or wail at the death or the sickness, but accepted the dispensation. During the time I was in her house she ministered to me to such an extent that I cannot adequately describe her kindness. Of her own free will she washed my clothes, arranged my bed, and polished my boots daily for three months. She washed down my bedroom daily with hot water, having herself heated it. Each morning she prepared me a tray with bread, butter, milk and coffee. When we had to leave that village that old lady wept on my shoulder. It is strange that I had never seen her weep for her dead son, but she wept for me. Moreover, at parting she would have had me take a fi-farang note for expenses on the road.” [What a woman! What a woman! I had never believed such women existed in this black age.]

“If there be any doubt of the quality or the color of the carpet ask for an audience of the Doctor Linley Sahib, if he is still in Amritsar. He knows carpets. Tell him all I have written concerning this old lady — may God keep her and her remaining household! — and he will advise. I do not know the Doctor Sahib, but he will overlook it in wartime. If the carpet is even fifty rupees, I can securely pay out of the monies which our lands owe me. She is an old lady. It must be soft to her feet, and not inclined to slide upon the wooden floor. She is well-born and educated.” [And now we will begin to enlighten him and the elders!]

“We must cause our children to be educated in the future. That is the opinion of all the Regiment, for by education even women accomplish marvels, like the women of Franceville. Get the boys and girls taught to read and write well. Here teaching is by Government order. The men go to the war daily. It is the women who do all the work at home, having been well taught in their childhood. We have yoked only one buffalo to the plow up till now. It is now time to yoke up the mulch buffaloes. Tell the village elders this and exercise influence.” [Write that down very strongly, Sahib. We who have seen Franceville all know it is true.]

“But as to cultivation: The methods in Franceville are good. All tools are of iron. They do not break. A man keeps the tools he needs for his work and his repairs in his house under his own hand. He has not to go back to the village a mile away if anything breaks. We never thought, as these people do, that all repairs to tools and plows can be done on the very spot. All that is needed when a strap breaks is that each plowman should have an awl and a leather cutter to stitch the leather. How is it with us in our country? If leather breaks we farmers say that leather is unclean, and we go back from the fields into the village to the village cobbler that he may mend it. Unclean? Do not we handle that same thing with the leather on it after it has been repaired? Do we not even drink water all day with the very hand that has sweated into the leather? Meantime we have surely lost an hour or two in coming and going from the fields.” [He will understand that. He chatters like a monkey when the men waste time. But the village cobbler will be very angry with men!] “The people of Franceville are astonished to learn that all our land is full of dogs which do no work — not even to keep the cattle out of the tilled fields. Among the French, both men and women and little children occupy themselves with work at all times on the land. The children wear no jewelry, but they are more beautiful than I can say. It is a country where the women are not veiled. Their marriage is at their own choice, and takes place between their twentieth and twenty-fifth year. They seldom quarrel or shout out. They do not pilfer from each other. They do not tell lies at all. When calamity overtakes them there is no ceremonial of grief, such as tearing the hair or the like. They swallow it down and endure silently. Doubtless, this is the fruit of learning in youth.”

[Now we will have a word for our Guru at home. He is a very holy man. Write this carefully, Sahib.] It is said that the French worship idols. I have spoken of this with my old lady and her Guru [priest]. It is not true in any way. There are certainly images in their shrines and deotas [local gods] to whom they present petitions as we do in our home affairs, but the prayer of the heart goes to the God Himself. I have been assured this by the old priests. All the young priests are fighting in the war. The Frenchmen uncover the head but do not take off the shoes at prayer. They do not speak of their religion to strangers, and they do not go about to make converts. The old priest in the village where I was billeted so long said that all roads, at such times as these, return to God.” [Our Guru at home says that himself; so he cannot be surprised if there are others who think it.] “The old priest gave me a little medal which he wished me to wear round my neck. Such medals are reckoned holy among the French. He was a very holy man and it averts the evil eye. The women also carry holy beads to help keep count of their prayers.

“Certain men of our Regiment divided among themselves as many as they could pick up of the string of beads that used to be carried by the small maiden whom the shell slew. It was found forty yards distant from the hands. It was that small maiden who begged us for our buttons and had no fear. The Regiment made an account of it, reckoning one life of the enemy for each bead. They deposited the beads as a pledge with the regimental clerk. When a man of the guarantors was killed, the number of his beads which remained unredeemed was added to the obligation of the guarantors, or they elected an inheritor of the debt in his place.” [He will understand that. It was very correct and businesslike, Sahib. Our Pathan Company arranged it.] “It was seven weeks before all the beads were redeemed, because the weather was bad and our guns were strong and the enemy did not stir abroad after dark. When all the account was cleared, the beads were taken out of pawn and returned to her grandfather, with a certificate; and he wept.

“This war is not a war. It is a world-destroying battle. All that has gone before this war in this world till now has been only boys throwing colored powder at each other. No man could conceive it. What do you or the Mohmunds or anyone who has not been here know of war? When the ignorant in future speak of war I shall laugh, even though they be my elder brethren. Consider what things are done here, and for what reasons.

A little before I took my wounds, I was on duty near an officer who worked in wire and wood and earth to make traps for the enemy. He had acquired a tent of green cloth upon sticks, with a window of soft glass that could not be broken. All coveted the tent. It was three paces long and two wide. Among the covetous was an officer of artillery in charge of a gun that shook mountains. It gave out a shell of ten maunds or more [eight hundred pounds]. But those who have never seen even a rivulet cannot imagine the Indus. He offered many rupees to purchase the tent. He would come at all hours increasing his offer. He overwhelmed the owner with talk about it.” [I heard them often, Sahib.] “At last, and I heard this also, that tent owner said to that artillery officer: ‘I am wearied with your importunity. Destroy today a certain house that I shall show you, and I will give you the tent for a gift. Otherwise, have no more talk.’ He showed him the roof of a certain white house which stood back three kos [six miles] in the enemy country, a little underneath a hill with woods on each side. Consider this, measuring three kos in your mind along the Amritsar Road. The gunner officer said: ‘By God, I accept this bargain!’ He issued orders and estimated the distance. I saw him going back and forth as swiftly as a lover. Then fire was delivered and at the fourth discharge the watchers through their glasses saw the house spring high and spread abroad and lie upon its face. It was as a tooth taken out by a barber. Seeing this the gunner officer sprang into the tent and looked through the window and smiled because the tent was now his. But the enemy did not understand the reasons. There was a great gunfire all that night, as well as many enemy regiments moving about. The prisoners taken afterward told us their commanders were disturbed at the fall of the house, ascribing it to some great design on our part; that their men had no rest for a week. Yet it was all done for a little green tent’s sake.

“I tell you this that you may understand the meaning of things. This is a world where the very hills are turned upside down, with the cities upon them. He who comes alive out of this business will forever after be as a giant. If anyone wishes to see it let him come here or remain disappointed all his life.”

[We will finish with affection and sweet words. After all, a brother is a brother.] “As for myself, why do you write to me so many complaints? Are you fighting in this war or I? You know the saying: A soldier’s life is for his family; his death is for his country; his discomforts are for himself alone. I joined to fight when I was young. I have eaten the Government’s salt till I am old. I am discharging my obligation. When all is at an end the memory of our parting will be but a dream.

“I pray the Guru to bring together those who are separated. God alone is true. Everything else is but a shadow.”

[That is poetry. Oh — and add this, Sahib:]

“Let there be no delay about the carpet. She would not accept anything else.”

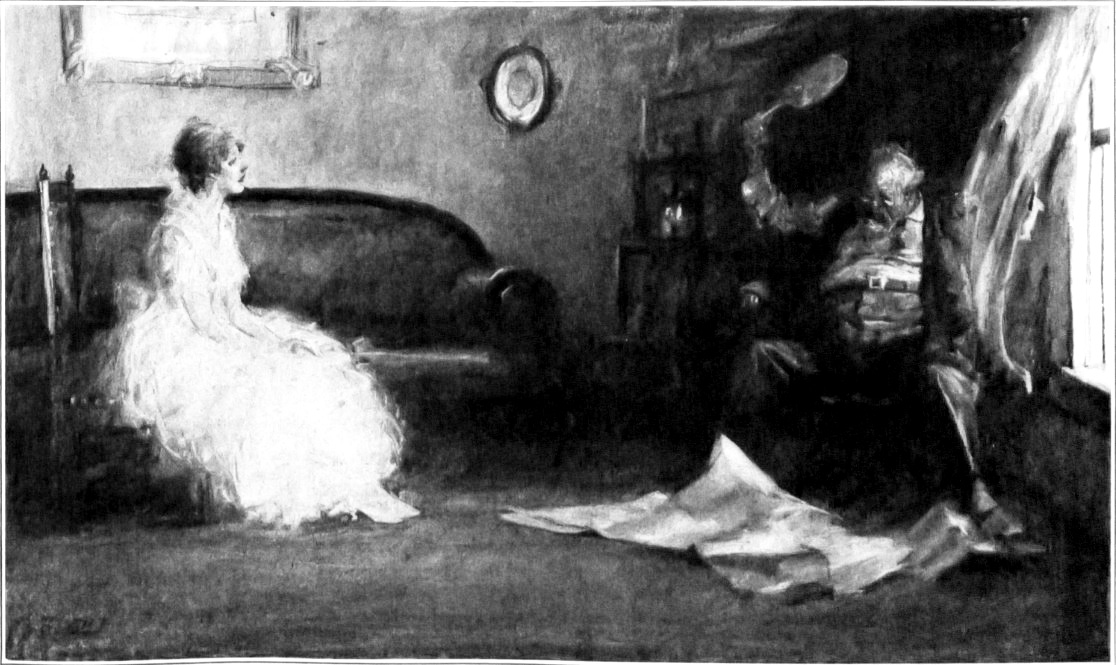

Featured image illustrated by Harvey Dunn, SEPS

“The Water’s Fine” by John Peter Toohey

A member of the famed Algonquin Round Table, John Peter Toohey also gave Harold Ross the idea to name his magazine The New Yorker, according to Dorothy Parker’s biography. Toohey wrote for magazines for much of his life before working as a theater publicist. His short story “The Water’s Fine,” about a theme park press agent who designs a publicity stunt for his ingénue crush, was later expanded into a novel called Fresh Every Hour. His thrilling, romantic short sets the scene by invoking the 1900s vaudeville hit “I Just Can’t Make My Eyes Behave” and concludes with a climactic chase on dirigible.

Published on November 8, 1919

Jimmy Martin’s heart persisted in acting like the well-known eyes of the young lady in the song. He just couldn’t make it behave. Up to the third week of his summer season as press agent at Jollyland, the big summer amusement park near New York, it had always been a fairly well-mannered and dependable organ, which performed its physiological functions with becoming regularity and which was not accustomed to respond to any external stimuli with anything beyond an occasional slight flutter. To be sure it had acted up a little three years back in connection with a certain dark-eyed beauty who presided over the destinies of the cigar counter up in the Grand Hotel in New Haven, but that had been only a slight attack and it had resumed the even tenor of its ways after a brief interval and had been unobtrusively going through its routine activities ever since.

A most prepossessing young person whose parents had inflicted upon her the name of Miss Lolita Murphy was directly responsible for the alarming symptoms already hinted at. From the precise moment that Lolita came within his ken Jimmy ceased to be a rational being in full control of his faculties; and his heart, in sympathetic accord with the agitated condition of its owner, began to put on an antic disposition and indulged in curious palpitations of a most annoying nature on the slightest pretext. The usual provocation at first was the sight of Lolita herself, but after a day or two even the thought of her produced a cardiac rataplan that would have done credit to the trap drummer of a jazz band.

Lolita, it may be mentioned in passing, lived up to all the implications of the somewhat picturesque cognomen given her by McClintock, the park manager, when Jimmy first pointed her out to his superior.

“She sure is Miss Lulu Looker,” McClintock had remarked emphatically.

Lolita was all of that and a little more. Jimmy was not a poet, and he was therefore unable properly to voice the feelings he had about her beauty. Had he been one he might have justly said that her cheeks seemed to have been kissed by the rosy flush of dawn; that in her sable eyes there lurked the eternal mystery of night beneath tropic skies; that her dark hair was as fragrant as the spices of Araby and that her lithe figure had all the gracile curves of a bounding antelope. As it was, he contented himself with the frequent repetition of the decidedly unpoetic expression “some gal,” but this represented to him all the ideas noted above and a liberal assortment of others equally glamorous.

Lolita hailed from a small city in Iowa, and ever since the memorable occasion when Maude Adams played Peter Pan in that city for one night only she had cherished a great and overwhelming ambition. Her father ran the drug store next door to the opera house and was a great crony of the manager’s. A number of boys and girls were picked up in each town to play the children in the Never Never Land scene and Lolita’s fond parent had inveigled the manager into selecting her as one of the group. It was a step that father was to regret vainly for many years, but on the night of her debut he was blissfully unconscious of the possibility of any bitter repining in the future and enjoyed the proceedings almost as much as Lolita did.

From that time on Lolita felt the call of the footlights and became convinced that, given the proper opportunities for the externalization of the emotional feelings that lay dormant within her, she was destined to become an international celebrity and the queen regnant of the English-speaking stage. Chauncey Olcott came to town a few weeks later and she persuaded father to work her in as one of the youngsters to whom he sang a lullaby in a high tenor voice down in the “glen,” which is always the setting for the third act of an Irish play.

After that there was no holding her. She became a student at Miss Amanda Holliday’s School of Dramatic Expression, which occupied three rooms on the second floor of the Turner Block on Main Street, and she participated in the semiannual entertainments given by the budding geniuses who were under the tutelage of that small-town preceptress of the arts. Versatility was her middle name. At one time she would play Ophelia in the mad scene from Hamlet, and appear later on the program in a Spanish dance with castanets, a lace mantilla and all the other necessary properties. Six months later she would combine the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet with an imitation of an imitation of Eddie Foy she had heard given by a monologue artist at the Orpheum Theater.

At the age of nineteen she was the town wonder. The dramatic editor of the Democrat-Chronicle predicted that within a short time “this talented daughter of our esteemed fellow townsman, Henry P. Murphy, seems destined to occupy one of the stellar places in the front ranks of the worthwhile artists of our fair country.”

Lolita moved on to New York armed with a letter of commendation from Miss Amanda Holliday setting forth that she was “worthy of consideration for any role no matter what its importance” and urging theatrical managers “not to neglect this opportunity of obtaining the services of one who is a mistress of the mimetic art in all of its manifold manifestations.” She also carried a full set of clippings from the Democrat-Chronicle, one half of her male parent’s attenuated account in the First National Bank and an overabundant supply of cheery optimism.

The metropolitan managers’ office boys were decidedly cold to the advances of this gifted daughter of the Middle West. They treated her with that air of careless indifference so characteristic of their profession. With one accord all the big and little producers decided to take a big chance and neglect the opportunity which Fate was offering them. They were unmoved by the clippings from the Democrat-Chronicle with which Lolita bombarded them through the mails, and they were callous to the eulogistic outpourings of Miss Amanda Holliday, copies of which accompanied each written request for an interview. Lolita’s cash reserve grew perilously low and disaster threatened. Then on a morning when disillusionment and despair moved in and took lodgings in her soul she saw an advertisement in a newspaper which was like a life buoy tossed to a drowning man.

“Ambitious Young Women Wanted for Stage Work,” it read. “Opportunity Afforded Ambitious Amateurs to Perfect Themselves in Dramatic Technic — Apply Immediately at Manager’s Office, Jollyland.”

Lolita, filled with high hopes, took a trolley to the great playground by the sea. There, Destiny handed her one of those cold douches that are sometimes held in reserve for those whose ambitions o’erleap themselves. The dramatic opportunity promised in the advertisement proved to be what might be vulgarly termed a job.

A great free open-air spectacle was in process of preparation at Jollyland under the supervision of a famous moving-picture director who specialized in that form of animated art technically known as serials. He had personally conducted a gazelle-eyed cinema celebrity known as June Delight through four fifteen-reel affairs of this sort, in which she had been threatened with mayhem, aggravated assault and battery, felonious wounding, and total and complete annihilation at the hands of numerous bands of cutthroats, bandits, thieves and white slavers. In the course of these proceedings she had performed every breath-catching feat that the festive imagination of the director had been capable of conjuring up, and had succeeded by a miracle in keeping out of both the hospital and the obituary columns of the daily press.

Now it was proposed to let the public have a close-up view of this death-defying marvel in the flesh in the act of performing one of her most famous exploits “before your very eyes and for your attention,” as the circus announcer would put it. To permit of this the director had evolved something which he called a dramatic spectacle and had persuaded the management of Jollyland to arrange for its production in a huge, specially constructed open-air auditorium as a special added attraction intended to put a final quietus on the presumptuous efforts of a rival group of showmen who were endeavoring to rouse interest in a new park just opened that summer.

Lolita found herself in a long line of applicants, many of whom were pathetically peaked and undernourished looking, and when her turn came to meet the director she made up her mind to pocket her pride and accept whatever fate offered rather than run the risk of finding herself in like straits. Ambition still fired her soul and she was determined not to return to the little old home town until she could enter it in something at least closely akin to a spirit of triumph. To be sure the opportunity offered her was not particularly roseate. It did not hold forth much promise of either pecuniary reward or even of passing fame, but it meant that Lolita would not have to telegraph home for funds and there was a faint glimmer of hope in a remark made by the director.

“You can mingle in the front ranks of the crowd,” he said. “We’ll pay you eighteen a week. There’ll be only two shows a day.” Then he had looked at her critically. “You’re almost a ringer for Miss Delight,” he concluded. “Maybe if you’re a good little girl I might take a notion to try you out as understudy.”

So Lolita Murphy, the pride of her home city, became a small and almost infinitesimal part of the great outdoor spectacle entitled Secret Service Sally, which was the big sensation of the Jollyland season.

In the role of an agent of the United States Secret Service the charming and fascinating June Delight was swept through a series of thrilling adventures set against spectacular backgrounds depicting scenes in Berlin, Tokio, Rio de Janeiro and other world capitals, and as a culminating feature she was pursued to the roof of a building in London by a howling mob which suspected her of being a spy in the employ of the Central Powers. She was saved from its hands, in the proverbial nick of time, by her fiancé, dashing Lieut. Thurston Turner, commander of the United States Dirigible N-24, who happened to be cruising about the neighborhood at the moment and who effected a rescue by circling his ship round the roof and deftly lifting the young woman into the shelter of the gondola which hung from the great gas balloon just as she was about to be beaten to death by the crowd.

Inasmuch as the spectacle was given in the open air it was possible to use for the purposes of this scene a real dirigible, which was manned by a crew commanded by one Bobby Wilkins, a personable young gentleman from Chicago who had come back from France with a major’s commission, a reputation for dare-deviltry as an aviator surpassed by no other ace in the American service, and a collection of a half dozen assorted war medals bestowed by three grateful nations. Bobby had left a snug berth as assistant to the president of a big varnish company to go into the Army, the said president being a somewhat indulgent parent who had sanguine expectations concerning his son’s commercial and industrial future and who was even now sending him daily wires to the Ritz-Carlton urging him to “cut the cabarets and get down to a solid rock foundation.”

Father labored under the delusion that Bobby was simply vacationing in New York. Had he had an inkling of just what his son was doing he would have — to use the young major’s own expression — “tried for a new altitude record himself.” He couldn’t be expected to know that dictating fool business letters and checking up the new efficiency expert’s monthly report of economies effected at the Dayton plant wouldn’t exactly appeal any more to an adventuresome young man who had been skyhooting through the upper reaches of the atmosphere for nearly two years and dodging German machine-gun bullets.

Bobby had overheard the general who commanded the aviation camp at which he was demobilized remarking about a request made by the moving-picture director that he recommend some aviator for the task of piloting the dirigible which was to play such an important role in the spectacle, and he had offered himself for the sacrifice just as a lark. He found the experience rare sport and until something giving greater promise of adventure appeared in the offing he was determined to go on with it. Twice a day he reached down and plucked up the beautiful Miss Delight as lightly as if she were a fragile doll while the assembled thousands, on the qui vive with excitement, burst into rapturous applause. In order to insure the peace of mind of Robert Wilkins, Sr., Jimmy Martin had consented rather reluctantly, it must be admitted — to respect the wishes of the impersonator of Lieut. Thurston Turner, U.S.N., who had expressed a desire to remain incognito. Otherwise the consequences might have been lurid.

Jimmy itched to give out a story concerning the social and business connections of the young soldier, but he had given his word and, being an ex-newspaper man, that was sacred. He temporarily forgot about Bobby and devoted his spare moments to figuring out ways and means for the sensational exploitation of Lolita Murphy, to whose charms, as previously recorded, he had become a shackled slave from the moment he first glimpsed her at rehearsal.

Lolita, it may be mentioned in passing, was a trifle discouraged at the comparatively slight opportunities for uplifting and otherwise ennobling the American stage offered by her participation in Secret Service Sally. Her name wasn’t even mentioned on the program. She figured under an impersonal heading at the bottom, together with a couple of hundred other young women who were listed as “Berlin citizens, Japanese geisha girls, South Americans, Londoners, etc., etc.”

It needed all the soaring optimism of Jimmy to keep her from slipping into a nervous decline. The press agent had obtained an introduction through the stage director, and his sympathetic interest in her temporarily sidetracked ambitions had won him her esteem and high regard from the beginning. Jimmy was a rapid worker and within three days from the time of their first meeting he had vowed his ardent and palpitating devotion, and though Lolita had not completely committed herself to a reciprocal affirmation she had succeeded, nevertheless, by devious and subtle devices not unknown to her sex, in conveying the distinct impression that the star of hope was visible in the eastern sky.

There came a night when Lolita’s disappointment was past all bearing and when she sobbed out on Jimmy’s shoulders a bitter protest against the fate that had driven her into believing that she was destined to be a great actress. They were sitting on the beach in the moonlight after the show, and off in the murky distance the great Sandy Hook light was blinking like some monster firefly.

“Jimmy,” she said half chokingly, “I just don’t belong. I wish I was back in Iowa.”

“Gosh, that’s an awful wish, girlie,” responded the press agent with a foolish attempt at a pleasantry which he instantly regretted. Lolita drew away from him quickly and flared up.

“Iowa’s all right,” she retorted. “It’s better than this lonesome place.” She lapsed almost immediately into a wistful mood. “It’s just ten o’clock there now and the movies are letting out and there’s a crowd in dad’s store and the fellows are treating the girls to sundaes or just plain ice cream and dad is fussing round and yelling to poor Porky Brooks to get a move on and keep the orders filled, and like as not he’s helping out himself. I want to go back, Jimmy; I want to go back.”

Jimmy touched her gently on the hand and then squeezed it softly.

“Listen, girlie,” he said comfortingly. “I know just how you feel — the cards ain’t runnin’ right and you want to quit the game, but I’m goin’ to cut in with a clean deck and start a new deal. I’m goin’ to fix things so that when you do go back for a visit to the little old home town and the old folks the Peerless Silver Cornet Band is goin’ to be down at the station, and the Mayor is goin’ to speak a few well-chosen words of welcome in the presence of a cheering crowd of friends and wellwishers. Leave it to me.”

Lolita laughed a little in spite of her mood.

“You’re a great little jollier, Jimmy,” she said, “and I’d like to believe you, but somehow I can’t. I’m a nobody, a small-town nobody.”

“But you’re goin’ to be a little Miss Lolita Somebody of the well-known world,” he responded cheerily, “before I get through with you. I’m goin’ to drop you right into the direct center of the front page of every paper in the U.S.A. from the New York Gazette to the Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, Rocket. You’re goin’ to make all the rest of them look like shrinkin’ violets on a foggy afternoon when I finish up with you. You just wait and see.”

“How long have I got to wait, Jimmy?” ventured Lolita, who was adrift in the realms of fancy, carried thither by the soothing cadences of Jimmy’s voice.

“Only until some afternoon when this June Delight person fails to show up. I hear she’s talkin’ of layin’ off for a few days. If that doesn’t happen by the middle of next week, I’ll get to her chauffeur and frame it so that she misses the show. Then we’ll pull the big act. If you’ll promise not to talk about it even in your sleep I’ll hand you a little advance information on the subject.”

Only the silent stars and the discreet moon shared Jimmy’s confidence with Lolita. Its general tone and tenor lifted that despairing daughter of the plains out of the rut of hopeless striving into which she felt she had fallen and filled her with such anticipatory delight that when she said goodbye at the door of her boarding house she impulsively reached forward and kissed him full on the mouth.

“You’re a darling!” she murmured.

“I’ll take an encore on that, girlie,” he replied. And he did.

II

Miss June Delight summoned Manager McClintock to her dressing room just before the Saturday-night performance and successfully simulated the classic symptoms of impending nervous prostration while she sniffed at a vial of smelling salts and submitted to the ministrations of a tired maid who gently massaged her forehead with her fingertips. Miss Delight in a voice that was barely audible informed the manager that she could not possibly endure the trying ordeal of further performances after that evening without a brief period of rest and that she was leaving for a week’s stay at a sanitarium on the following morning.

McClintock gave voice to low moans and flew other signals of distress, but Miss Delight was obdurate to his more or less frenzied expostulations and remarked that though she was disturbed at having to disappoint her dear, lovely, friendly public she felt that her health was the prime consideration. The manager was in a surly mood when he left her to seek out the stage director.

“Who’s the understudy?” he inquired.

“She calls herself Lolita Murphy,” replied the director, “but I understand there’s a certain party connected with the publicity department who calls her even flossier names than that.”

“Jimmy’s gal, eh?” commented the manager. “Well, she’s there with the looks anyway. Has she had a rehearsal?”

“She’s been through the thing roughly with the rest of the understudies, but I can have the whole troupe called for tomorrow morning and we can run straight through. We’ll get out the dirigible and go through with the rescue stunt. We mustn’t fall down on that. The little lady seems to be there with the nerve, but I’d like to try it out.”

Jimmy was permitted to break the news to Lolita. He met her after the performance that night and imparted the glad tidings. When he left her he gave her a final word of caution.

“Keep the little old nerve up, girlie,” he said earnestly, “and we’ll wake up the whole country on Monday morning.”

“I’ll try, Jimmy,” she whispered. “You’re just the — well, just the dearest boy I’ve ever known.” On the following morning Lolita, athrill with excitement and a little nervous, assumed the title role in Secret Service Sally at a rehearsal, to the complete satisfaction of McClintock, the stage director, and Jimmy Martin. The latter watched her with adoring eyes and when she successfully essayed the sensational rescue scene he was moved to wild and clamorous applause, which sounded a bit startling in the great empty auditorium. Under Bobby Wilkins’ expert direction the big clumsy dirigible was maneuvered round the edge of the roof and Lolita was lifted into the car by the former ace with such adroit ease that the whole thing seemed to be simply part of a casual everyday occurrence. When it was over and Lolita had been safely landed back on earth and had received the congratulations of everyone concerned she drew Jimmy aside and clutched at his arm for support.

“I’m ready to faint,” she said weakly. “I believe I would have up on the roof when I saw that big thing coming toward me if that fellow hadn’t grabbed me off so quickly.”

“You need a little nap,” responded Jimmy soothingly. “The worst is over and the best is yet to come. Don’t forget that young Mr. Arthur H. Opportunity has a date with you this afternoon and that the big splash is due tomorrow morning. Now you go in and get a little sleep and I’ll have a talk with my friend the handsome lieutenant. I fixed things with him last night, but I’ve got to go over some details again.”

A few minutes later the press agent was closeted with Bobby Wilkins in the hangar in which the dirigible was housed. The park gates had just been opened for the day and crowds of holiday merrymakers were surging through them in quest of the fifty-seven varieties of feverish and hectic entertainment which Jollyland provided for those in search of diversion.

III

If anyone had called Jimmy Martin a psychotherapist he would promptly have denied the soft impeachment first and then asked for a dictionary and an explanatory blueprint. And yet as a direct result of a random idea which had bobbed into his active mind a few weeks before he was unconsciously serving in that capacity for a large and ever-increasing throng of metropolitan society women of varying ages who flocked to Jollyland in search of a new thrill which he had provided. The winding up of war-charity work which had followed close upon the return to these shores of the larger part of the American Army had turned many of these women back upon their own resources; and their innate restless activity, which had found such an altruistic outlet in new channels for several years, now imperiously demanded fresh excitement, and it was this that Jimmy offered them.

On the occasion in question Jimmy had overheard a coy young debutante who was watching a performance of Secret Service Sally remark to a group of friends who accompanied her that she’d just love to go up on the stage and mix with the crowd! That was enough for the press agent. Ten minutes later, during the intermission, he escorted the entire party behind the scenes, and under his guidance they participated in the London episode which concluded the show. They mingled with the crowd of supernumeraries and entered into the proceedings attendant upon the thrilling dirigible rescue with such gusto that the stage manager gave Jimmy carte blanche to encourage the idea.

It happened that in this particular party were several of the socially elect and the papers next morning carried extensive stories chronicling the event, coupled with the announcement that the park management would, throughout the season, be pleased to extend the privilege of participating in the entertainment to other groups who might wish to take advantage of the opportunity for this unusual form of entertainment. Society seized upon the idea voraciously and Jollyland parties gave a new fillip to the summer season at all the Long Island resorts. Elderly matrons of ample girth vied with the members of the younger set in setting the pace, and in many instances came again and again to become a part of the great spectacle. For the first time in its history Jollyland began to figure in the society columns of the daily press, and great was the prestige which Jimmy enjoyed in McClintock’s eyes as a result.

The particular luminary of the Long Island season at the moment and the prospective lion of the month of August at Newport was none other than the Hon. Betty Ashley, daughter of the second Lord Norbourne, and the most talked about young woman in English society for a period the beginnings of which antedated the war by several years. Before the great European conflagration, the Honorable Betty, though then still in her early twenties, was a European celebrity. Spirited, impulsive and headstrong by nature she had early rebelled against the ultraconservative traditions of her family and had so thoroughly flouted convention that her name was on the tip of the tongue of everyone in the tight little island. She began it by publicly slapping the face of a certain deposed kinglet who had sought refuge and a safe haven in England and whose sole offense had been a mild protestation of love, made at a fashionable garden party.

There had followed her sensational and entirely unarranged presentation of a petition for woman’s suffrage to England’s monarch himself at a formal court reception — an incident which sent her dignified father to his bed for two weeks; her arrest on suspicion of being implicated in a militant attempt to set fire to the House of Parliament and her subsequent acquittal after she had refused to make any defense against a damaging array of circumstantial evidence; her jilting of the Earl of Maidsley in an explanatory and derisive letter to the Times; her winning of the amateur tennis championship; and a host of other incidents of an unconventional nature.

Then the war had come and she had gone over to France in the first months as a motor driver and had still managed to keep in the public eye for five years despite the somewhat considerable amount of attention devoted in the newspapers to the great struggle. She had, for one thing, won a D.S.O. for bravery under fire in the First Battle of Ypres; and she had, for another, been reprimanded in orders for organizing a ball at a certain château occupied by the staff of a certain corps during the absence of the commanding general at a conference at G.H.Q.

Now she had come to the United States for the first time and had materially assisted in putting zest and punch into a round of festive house parties on Long Island given by prominent members of the swiftest-moving coterie of the so-called smart set. Small wonder that when she heard of the expeditions to Jollyland which were enjoying such a vogue she should elect to organize one herself.

“I’m not entirely a rank amateur, my dear,” she confided to her hostess when the party was preparing to depart. “I went on for two nights running in the chorus at the Alhambra last winter on a five-pound wager and I’d have stuck it out for a whole week for the fun of it if the pater’s blood pressure hadn’t been running abnormally high. The old dear would have gone all to smash if he had found out, and he might have if I’d kept on.”

The Honorable Betty, her dark beauty set off by a rose-pink silk sweater and a tam-o’-shanter to match, was in the first car of the string of six which disgorged a laughing crowd of merrymakers in front of Jollyland on Sunday afternoon. They made for the big arena immediately, as it was within a few minutes of the advertised time for the ringing up of the curtain on the great spectacle. The Honorable Betty let it be known to an usher, who was duly impressed by her air of authority, that she craved an immediate interview with the manager. McClintock, still disturbed at the defection of the capricious Miss Delight, responded grudgingly; was apprised of the identity and mission of the distinguished visitor, and sought out Jimmy Martin in great excitement. He found the press agent back on the stage.

“Say, young fellow,” he said enthusiastically, “I’ve got a Monday-morning story for you all ready-made and ready to try on! This Betty Ashley who’s been grabbing off space all over the world for a long time and who’s the big noise with the real folks over here this summer is out in front with a crowd right out of the Social Register and she wants to go on in the London scene. I told her she could. Get busy now and prepare for a general assault on the press.”

Jimmy received this intelligence with a glumness that rather annoyed McClintock.

“What did she want to pick out today for?” he inquired uneasily.

“What’s the matter with today? It’s the best day possible for a good break for us. The papers are always glad of anything that makes a noise like a story on Sunday. What’s the matter?”

“Oh, nothin’,” replied Jimmy absentmindedly; “only I wish she’d waited until the middle of the week. I was kinda figurin’ on — Oh, nevermind; it’ll be all right.”

IV

An acute observer would have detected signs of suppressed excitement in the general demeanor of Jimmy Martin during the progress of the early scenes of the great spectacle in which Lolita Murphy was essaying the leading role for the first time on any stage. He had exchanged his customary cigarette for the solace of a particularly formidable-looking cigar, which he puffed at nervously as he sat in the manager’s box with his cap pulled down over his eyes. His whole body was tense and rigid, and though there was a look of adoration in his eyes there was something more — a vague something that seemed to spell apprehension.

Justice compels the admission that Lolita was doing herself proud. She moved through the thrilling situations of Secret Service Sally with the ease and calm assurance of a veteran and more than merited the applause which the vast holiday audience showered on her. When the curtain rose on the final scene — the one depicting the streets of London — the audience, keyed up to expectant excitement by the gaudy promises of the program, held its collective breath and Jimmy sank his teeth viciously into what remained of his cigar. McClintock slid into the seat alongside of him.

“That gal of yours is sure making good!” he remarked good-naturedly. “If she goes through to the finish as nicely she’ll find a surprise in her envelope on Saturday night. There’s that English society dame and her party strolling along just as if they were back in dear old Lunnon. I had Lawrence, the assistant stage manager, go on with ’em to put ’em wise to all the business.”

The mimic street on the stage was thronged with a motley crowd of supernumeraries who were supposed to represent the populace of the British metropolis out for an airing on a bank holiday. The rose-pink sweater of the Hon. Betty Ashley was the most conspicuous object in view. That patrician lady bobbed in and out among the others, apparently having the time of her life and urging her friends, with violent pantomime, to enter into the festivities with something akin to her own enthusiasm.

Presently the audience heard a murmur pass through the crowd on the stage and Jimmy’s acute ear detected the muffled purr of the motor on the dirigible, which was at that moment maneuvering for position and awaiting its cue two hundred feet in the air just behind the backs of the last row of spectators. The press agent grabbed the railing in front of him and leaned eagerly forward. He was watching the right side of the stage.

A motor car shot out of the wings through a lane in the crowd. In it sat Lolita Murphy in the role of queen of the American Secret Service. It was plain that she was simulating great anxiety and that she was being followed. She looked apprehensively over her shoulder and the audience could catch excited shouts of “Stop her! Stop her!” A gigantic bobby stepped directly in the path ahead of the car and drew his revolver. The chauffeur pulled a lever and the car stopped abruptly. A man on a motorcycle came dashing up.

“Arrest her!” he shouted and he sprang from the saddle. “She’s a German spy from the Wilhelmstrasse.”

Lolita looked about furtively, poised herself for just a moment and then leaped out of the car, overturning an athletic super and making for a doorway as the crowd broke into frenzied cries of “Kill her! Kill her!” The incident had been rehearsed with the utmost regard for actuality, and as the mob surged after the suspected spy the vast throng of spectators swayed with excitement like a field of tall grass in a breeze. Lolita reached the safety of the doorway by almost the fraction of an inch and disappeared. The crowd poured in after her and McClintock caught Jimmy’s arm as he caught sight of a vanishing flash of rose-pink.

“Damned if that English dame isn’t right in at the death!” he said excitedly. “She’s going up on the roof.”

Jimmy didn’t reply. He was watching the roof of the make-believe building with eyes that were strained and staring. As Lolita emerged from the hatchway and plunged forward with a fine gesture of despair, he looked back over his shoulder for a moment and noted that the N-24 was slowly swinging forward and that the alert and eager face of Bobby Wilkins was visible over the edge of the car which hung from the rear of the big balloon.

Lolita held out appealing hands and gave voice to cries for assistance. The crowd, in the vanguard of which was a lady in a rose-pink sweater, with cheeks that were flaming and with eyes that were dancing, swarmed up through the opening and surrounded the suspected spy. The supernumeraries’ voices became a blended babble of inarticulate cries and 3,467 spectators watched the developments in a tense silence.

Nearer and nearer swung the great dirigible. Lolita was now in the hands of the mob, with which she struggled fiercely. As the N-24 swung round the corner of the roof she turned as per instructions, but Jimmy noticed with a gasp of concern that she had turned in the wrong direction and that she was making her way to the wrong side. She was evidently bewildered. Bobby Wilkins was leaning out of the car with his arms outstretched and was beseeching her to run toward the other side of the roof. In another five seconds the dirigible would have passed on and the spectacular finish of the big show would be ruined. McClintock swore softly. Jimmy sat as one entranced.

Some of the supers were pushing Lolita to the other side, but she seemed to be in a panic and struggled with them as if still acting the earlier scene. At this juncture Jimmy noticed that a lady in a rose-pink sweater had run to the edge of the roof, just above which the dirigible was moving, and that she was holding up her arms. His cigar dropped from his mouth a second later when he saw Bobby Wilkins grab her outstretched hands, swing her clear of the roof and pull her into the car as the great dirigible finally cleared the scenery building and in quick response to the hand of the pilot in the front car nosed her way upward at a higher rate of speed. The curtain fell and the repressed excitement of the great audience found vent in tumultuous applause. The thing had happened so quickly that there were apparently few who had noticed that the wrong young woman had been saved from death by the timely arrival of Lieut. Thurston Turner, U.S.N.

“What a whale of a story!” chortled McClintock, gripping Jimmy’s arm so fiercely that the press agent winced with pain.

“Yes, isn’t it?” responded Jimmy dreamily as he watched the N-24 winging her way over the park and out toward the sea. The spectators had risen from their seats and were applauding again as a big American flag was unfurled from the rear car of the dirigible.

The balloon kept on its way toward the ocean, and as McClintock noticed that it didn’t make the turn it usually did when it reached the giant roller coaster that ran along the shore a puzzled expression came over his face. If he had looked at Jimmy sharply just then he would have observed the first beginnings of a pleased smile tilting the corners of the press agent’s mouth. A minute passed and the great yellow gas bag receded farther and farther in the distance. McClintock stepped down and borrowed a field glass from a spectator. He glued his eyes to it for a few moments and then dropped his arms. His face had gone pale.

“His motor’s dead,” he said weakly, “and he’s drifting out to sea. The propeller’s stopped and he’s being carried out by this land breeze. We’ve got to do something — we’ve got to get help of some kind.”

The manager was plainly worried. He pressed the glass on Jimmy, who had followed him out of the box, and the latter watched the clumsy balloon, now at the mercy of the stiff breeze which had blown up, slowly but surely disappearing in the opalescent haze which hung above the line where sky and ocean seemed to meet. The owner of the glasses had overheard McClintock’s remark and had passed the word on to his neighbor. In two minutes the news had spread through the great crowd, and thousands of eyes were focused on the drifting speck, which presently vanished. McClintock pushing Jimmy before him started for the main office and found himself surrounded by an excited group of men and women. An upstanding chap in a British major’s uniform who wore a cap on which was the red-velvet band of a staff officer stepped forward.

“We’re Miss Ashley’s friends,” he said with a touch of feeling in his voice; “and we’ll do everything we can to assist you. She’s a bit untamed, sir, and she shouldn’t have done that wild foolish thing, but she’s the best woman alive for all that, and now that she’s in danger we’re going to help you see her out of it. Has that dirigible got a wireless on board?”

“No,” replied the manager. “There wasn’t any need for one. Since it’s been here it’s never been more than a mile or two away from the hangar before.”

“That’s bad — damned bad,” responded the officer. “Of course maybe they’ll be able to fix the engine, but we can’t take chances on that. If you’ll let me use your telephone I’ll call up our embassy in Washington and get them to get in touch with the Navy Department. We’ll have all the ships in range of the Arlington station on the lookout in an hour.”

The thoroughly sobered group of pleasure seekers who had accompanied the Honorable Betty to Jollyland two hours before followed McClintock and Jimmy Martin into the offices in the administration building and talked in low voices while the major began to fuss in the telephone booth with the long-distance operator. Some of the women were weeping.

V

In the seclusion of his private office Jimmy telephoned a press syndicate, the police and the nearest United States lifesaving station, in the order named, while McClintock, who was plainly tremendously worried, paced restlessly up and down the floor, pausing occasionally to glance out of the window at the broad expanse of sky and sea, in the vain hope that some sight of the lost dirigible might greet his eye. Just as Jimmy began calling up the metropolitan newspaper offices in a fine frenzy of excitement both men heard the office door slam violently. They turned in unison and found themselves confronted by Lolita Murphy. Gone were the shy manner, the demure smile and the air of coy ingenuousness. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes were blazing, and her whole manner indicated that she was in what is generally referred to as a “state of mind.”

“Hello, girlie,” Jimmy called out pleasantly. “What’s the matter?”

“Don’t you dare girlie me, Mr. James T. Martin!” retorted Lolita in a voice that she was palpably trying, with a great effort, to keep at an even and menacing tone. “Don’t you dare to speak to me again! I came in to tell you that and to let you know that even if I do come from a small town I can’t be fooled by any New York — by any New York — bunko man!”

Her voice broke on the last word and tears came into her eyes despite the struggle she was making to hold herself in hand. Jimmy came toward her, but she waved him off hysterically. McClintock watched the proceedings in amazement.

“What’s the idea, Lolita?” began the press agent beseechingly. “I don’t get you. I don’t understand.”

“Don’t try to tell me that,” ran on Lolita, who was now half sobbing. “Don’t try to tell me that you didn’t turn me down when that English girl came into the park with all those society people and that you didn’t get together with that Wilkins fellow to have me left there so you could get a better story out of it with her. You fixed it all up and you can’t tell me that you didn’t because I just know, that’s all. I have a sweater on under my dress so’s I wouldn’t catch cold and I had milk chocolate in my pocket and I’d written home to mother about its going to happen and telling her not to worry about anything she might read in the papers the first day, and now nothing’s happened at all to me and I’ve been made a fool of and it’s all your fault and if you ever try to come near me again or speak to me I’ll slap your face, Mr. James T. Martin, I’ll slap your face. Do you hear me, Mr. James T. Martin, I’ll slap your fresh little face!”

She was gone before Jimmy could remonstrate. The door closed behind her with a more reverberating bang than the one which had heralded her entrance. Jimmy dropped into the nearest chair and gazed vacantly into space. McClintock shook him roughly by the shoulder.

“Say,” he shouted, “what in the name of glory is this all about?”

“She handed me the mitt, Mac — she’s handed me the mitt, and she wouldn’t even let me explain,” responded Jimmy brokenly. “It’s the real heart-throb stuff this time, Mac, the real heart-throb stuff. I had everything framed up for her, and this English jane just drops in like a joker tannin’ wild and wins the hand.”

“You had what framed?”

“Why, this drifting-out-to-sea stunt,” replied Jimmy in a dead voice.

“This drifting out to sea — You don’t — you can’t mean that this thing is a plant!” gasped the manager incredulously.

“Of course it is!” returned the press agent with something of the old note of self-assertiveness in his voice. “I had it all fixed up for Lolita, and now this society dame is goin’ to get away with all the headlines. When I saw Wilkins pull her into the car I didn’t think he’d go all the way through, but it looks as if he’s decided to. There’s no use worryin’ about it. Every little thing is comin’ out all right — and, say — don’t forget to remember that it’s goin’ to be some story now — some story!”

“Just let me get this big idea through my head,” persisted McClintock. “What happens next?”

“Of course his motor hasn’t really gone dead,” replied Jimmy. “He’s just ordered his engineer to shut it off so they can drift with the wind. That was all framed up between us. He’ll probably turn on the gas again and cruise round out of sight of land for a couple of hours and shut off his engine every time he sees a ship comin’ in sight. That’ll be an alibi for the story. When the little old sun starts to sink in the west he’ll turn that big bag toward the Jersey coast and he’ll make a landing just before dark at a place we picked out yesterday morning. He’s going to lay under cover there, and we’ll keep the country guessin’ all day tomorrow.”

“But someone will see him land,” criticized the manager.

“I don’t think there’s a chance of that,” replied Jimmy jauntily. “We picked out a spot that’s as lonesome lookin’ as an iceberg. There isn’t a house within two miles and there’s nothin’ but marshland all round. There’s one little place right in the center that’s high and dry. That’s where he lands. Wilkins has got his car planted a couple of miles away and his chauffeur is goin’ to be right on the job in a rowboat — you see there’s a little creek that runs through the swamp — and the girl is goin’ to be taken away in the boat and slipped away to a hotel — that is, Lolita was goin’ to be slipped away and was goin’ to keep dark until she got the signal to appear again. Maybe this society queen’ll be game enough to go through with it just for the fun of the thing.

“We were goin’ to keep the agony up until tomorrow night at the earliest, and maybe until the day after tomorrow. Then Wilkins was goin’ to telephone that he’d just landed after bein’ tossed about in the air and all that, and Lolita was goin’ to have a nervous collapse and be interviewed in bed by a flock of reporters with a couple of trained nurses and three doctors hovering round in the offing. You can fill in the other details yourself. Anyhow, it’s a grand little notion for a story, even if this Betty Ashley person doesn’t come through. We’ll know about that tonight.”

“How so?”

“Why, the chauffeur has instructions to telephone me the minute he gets to the hotel. That ought to be not later than nine-thirty.”

“Why didn’t you tell me all about this beforehand?”

Jimmy smiled a bit guiltily before replying.

“I had a hunch that maybe you’d put the kibosh on the whole scheme because I was featurin’ a certain party too much,” he responded. He grew serious again for a minute and a far-away look crept into his eyes. “Say, Mac,” he went on, “I had a number that called for the grand prize and I’ve lost the ticket. It’s rotten luck. From the way she spoke a few minutes ago I’ll bet I don’t ever get out again, not even on probation.”

“That’ll be all right,” consoled McClintock. “I’ll fix that part of it for you. It’s a great story even if the Hon. Betty Ashley doesn’t go through, and if she does — why, if she does it’ll be the biggest thing ever pulled off in this country. Think of that for a little while.”

The press syndicate and the metropolitan newspapers were inclined to be a bit skeptical of the facts which Jimmy telephoned them at the outset, but outside confirmation was forthcoming promptly and within two hours after Maj. Bobby Wilkins and the Hon. Betty Ashley had disappeared in the general direction of the open sea the story was the sensation of the summer in journalistic circles.

A squad of picked feature writers invaded Jollyland in quest of detailed particulars concerning the events leading up to the beginnings of the ill-fated balloon trip; seven sob sisters motored to the palatial home at which the Honorable Betty was a house guest and interviewed a weeping and distraught maiden aunt of that lady, who had been acting as a submissive chaperon and who was certain that when “dear Ned, her father, hears the news he’ll froth at the mouth and have a stroke”; cables were frantically dispatched to London instructing correspondents to break the news to dear Ned and watch the results; city editors pawed over assortments of photographs of the beautiful heroine and conferred with art-department heads as to the most suitable ones to use for decorative layouts; dozens of leg men were sent out to points along the Jersey and Long Island coasts with directions to watch for any possible news of the return of the balloon and to keep on the lookout for any pleasure-yacht owner who might have seen the dirigible after she passed out of sight of land; the Washington offices were instructed to post a man in the Navy Department all night long to watch for any wireless news that might come flashing back from the torpedo-boat destroyers which at the urgent solicitation of the British Ambassador were to be sent out to scour the sea in search of the missing airship, and it was unanimously decided at editorial councils in every office to let the story lead the paper the following morning unless some great unforeseen national or international calamity transpired in the meantime.

Jimmy Martin became the focus point of more importunate news gatherers than he had ever fancied in his wildest dreams would assail him for information, and when a delegation of correspondents from a half dozen London papers looked in on him at eight o’clock and told him that they had been instructed to rush as much stuff as the cables would carry he almost passed into a trance.

“Mac,” he confided to the manager when the English correspondents had gone, “I feel like the fellow who looked at the giraffe and said, ‘There ain’t no such animal.’ There ain’t no such story. It’s a dream.”

“Well, I’ve left instructions that we’re not to be called,” returned McClintock. “Let’s dream a little more.”

In the star dressing room on the big stage of the open-air auditorium Lolita Murphy was getting ready for the evening performance of Secret Service Sally and was making a brave effort to control herself. She was as forgotten as yesterday’s newspaper, and the realization of it sent great tears of bitter disappointment coursing down her rouged cheeks into the make-up box on the little table in front of which she sat.

VI

It was nearly midnight when Bobby Wilkins’ chauffeur reported over the telephone to Jimmy Martin and McClintock, who had been keeping anxious vigil in the office all night.

“There ain’t a sign of him,” he said hurriedly. “I waited right where you told me to wait and if he’d been anywhere within a couple of miles I could have seen him after it got dark. The moon has been shining bright for a long time and I had a pair of glasses with me. I’m afraid it’s all up with him if he hasn’t landed someplace else along the coast. It’s tough for all of us if anything’s gone wrong, ain’t it?”

The chauffeur was instructed to make another trip to the selected landing place and to stay there until dawn, when relief was promised. Jimmy was pale and overwrought when he hung up the telephone receiver and turned to McClintock.

“If he had landed any place else,” he remarked, “he’d have made every effort to get to a phone. He’d know we’d be worried. Gee, Mac, supposin’ somethin’s happened to ’em. If there has, little old Robert B. Remorse’ll be my side partner for life. He told me he’d be prepared for all emergencies and he’s there with the nerve, but maybe they ran into a squall or something. Why’d I ever think of this stunt? I’ve got too much imagination, Mac. I’ve got to teach it to lie down and behave.”

The two sat up all night, smoking incessantly and discussing the variety of fates which they fancied might have overtaken the adventuresome Bobby Wilkins and his distinguished fellow passenger. Jimmy called up one of the newspaper offices every fifteen minutes for news, but there wasn’t any worth mentioning. The dirigible had not been sighted by any ship with which the navy wireless had been able to get into communication and the half dozen destroyers sent out to search for it were reported to be without definite information.

The entire country seethed with the story in the morning. The press syndicate had carried fifteen hundred words into every newspaper office in every city of importance from coast to coast, and the big dailies in Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston had three and four column stories from their metropolitan correspondents, liberally illustrated with pictures of the Honorable Betty, who was one of the most photographed women of her time. McClintock, who had no knowledge of Jimmy’s promise to keep Bobby Wilkins’ real name out of print, had blurted it out to a group of reporters in the evening, and the salient facts concerning the modest wearer of six war medals were incorporated in all of the accounts. Robert Wilkins, Sr., forgot that he was a mere business machine, wiped a few tears out of the corners of his eyes, looked tenderly at a picture of a curly-headed boy he always kept in one of the drawers of his desk, and started East on a special train.

The total haul in the New York morning papers was seventy-six columns of solid reading matter and thirty-eight photographic illustrations. Every angle of the story was covered in great detail and in addition to the main narrative there were extended biographical sketches of the Honorable Betty and of Bobby Wilkins. There were cabled stories from London concerning the festive career of the former which contained an expression of deep concern from the British premier. There were also cabled eulogies of the one-time ace from personages no less important than the American commander in chief in France and the generalissimo of the Allied Armies. All in all, it was the most spectacular feature story in years and the greatest achievement in the history of American press agentry. McClintock admitted that much when the first editions came in.

“Jimmy,” he said, “it’s a dog-goned shame that you’ve got to lie low and never get any credit for this. Still, you’ve got company. I was reading in the paper the other day that there’s a well-defined rumor that the more or less celebrated covenant of the well-known League of Nations was finally framed up by a clerk in the British Foreign Office. You can drop over later on and take a little drink with him and cry it all out on each other’s shoulders.”

Jimmy’s only response was a mournful attempt at a smile. He lit another cigarette, jerked out of his chair and began to swear softly as he walked up and down the room. He made a vicious lunge with his foot at a wastebasket and kicked it through the door into the next office. Then he took off his soft hat, rolled it into a lump and slammed it down on the floor with a wide sweeping gesture.

“I don’t mind that so much,” he said testily. “After landin’ a smear like that, though, I’d kinda like to have a good time with myself for a few minutes. I’d kinda like to throw a few assorted flowers up in the air and let ’em drop on me, but I’m so gosh-darned worried about what’s actually happened that I can’t have even that much fun.”

His anxiety increased as the day wore on and the early editions of the evening papers, which played up the story even more extensively than the mornings, failed to buoy him up. There was still no word of the N-24 and Navy Department officials in Washington were reported to be gravely alarmed at the possibilities.

At noon the British Embassy gave out the announcement that a “distinguished person” had cabled for detailed information and had begged to be kept in hourly touch with the developments. Flaming headlines carried the legend: King Anxious About Lost Dirigibles. Upon reading this, three rival publicity promoters, who had suspected the presence of the fine Italian hand of Jimmy Martin in the proceedings from the beginning and who had forgathered for lunch in their favorite club, simultaneously started out on a joint jamboree that was to become a memorable minor historical incident in the turgid annals of the White Way. It offered the only means of escaping from the tragic feeling of profound and passionate envy that surged up from the very depths of their beings.

At three o’clock as Jimmy, red-eyed and haggard, nodded at his desk between telephone calls, a messenger boy dropped a cablegram in front of him. He tore it open and gazed at this cryptic message:

“HAMILTON, BERMUDA.

“JAMES T. MARTIN,

“Jollyland Park,

“Coney Island, N. Y.

“Come on in — the water’s fine — give my regards to Lolita but can’t say I’m sorry it happened as yet.

BOBBY WILKINS.”

Jimmy gave a second look at the heading and rushed into the next office, where McClintock was snoring sonorously on a sofa. He shook the manager savagely and waved the cablegram in front of his eyes.

“All’s right with the world, Mac!” he shouted joyously. “They’ve landed in Bermuda. Can you beat that fresh son of a gun doin’ a thing like that? What’s the big idea, I wonder?”

McClintock grabbed the message and read it hurriedly.

“I guess maybe he’s mailing the answer,” he remarked. “It beats me. You’d better get a wire off to him asking for particulars.”

The shrill summons of the telephone brought Jimmy back into his own office the next moment. The voice of his friend, Lindsay, the day desk man of the press syndicate, came over the wire in crisp staccato sentences.

“Got some news for you,” he said. “It’s going to make this morning’s headlines look sick. Here’s the way our first bulletin reads:

“WASHINGTON, D. C., July 7 — The British Ambassador has just given out the following cablegram received from the Governor-General of the Bermuda Islands: ‘Please announce to press the marriage this morning in St. John’s Chapel, Hamilton, of the Hon. Elizabeth Ardsley Ashley, eldest daughter of the Earl of Norburne, of London, England, to Robert Benjamin, Jr., only son of Robert Benjamin Wilkins, Sr., of Chicago, Ill., U. S. A. The ceremony was entirely informal.’

“I’m ordering three thousand words from our Bermuda correspondent,” went on Lindsay, “and I’m having London break the news gently to dear old dad. I suppose if I come down on Sunday with the wife and the kiddies you could slip us into a few of your side shows?”

“Say,” responded Jimmy exultingly, “you’re goin’ to get a life pass good for each and every attraction within the big inclosure. Excuse me, won’t you? I’ve got to write out a request for an armistice to a certain party. You see I’ve just figured out what the bridegroom meant in a wire I got five minutes ago.”

As he hung up the telephone and swung round in his swivel chair the door leading into the hall opened ever so gently and the pale and tear-stained face of Lolita Murphy peered through the opening. Jimmy gazed at her, open-eyed, as she came slowly into the room. He noticed that she had a crumpled bit of paper in her hand.

“Jimmy,” she said timidly as she held out her arms in appealing suppliance, “I’m just a — just a foolish small-town kid. I didn’t understand, I didn’t understand.”

Jimmy in a daze took the paper which she held toward him. It was another cablegram. He smoothed it out, and the peace that passeth understanding settled down upon him as he read these words:

“HAMILTON, BERMUDA.

“LOLITA MURPHY,

“Jollyland Park,

“Coney Island, N. Y.

“Won’t it ease your disappointment a little to know that the mad impulsive thing I did yesterday and the rash act I have just committed in the chapel have transformed me into quite the happiest woman alive? Bobby has told me all about everything and he fears that you may think your friend Mr. Martin had a finger in the pie. He had nothing to do with it, my dear — it was just fate. Bobby is wiring some advice to Mr. Martin. See that he heeds it. Our best regards to you both.

“ELIZABETH ASHLEY WILKINS.”

McClintock coming into the room just then tiptoed out again and closed the door softly behind him, thus proving himself to be a gentleman of singular tact and discretion.

Featured image: Illustrated by James H. Clark / SEPS

The Remarkably Boring Signing of the Treaty of Versailles