Financial Guidance: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

Frequently I am asked: “Is financial advice worth it?” The underlying question is whether, in the end, you will have more money or less for having paid for such advice.

The simple answer is that good financial guidance can easily be worth many, many times what is charged for it. On the other hand, a great deal of what passes for advice out there in the marketplace is worth nothing. The challenge lies in discriminating between the good, the bad, and the worthless.

It would take far more than one column to describe which financial assistance has real value. Indeed, it would take a book. A long journey begins with a single step, though, so let’s start with a few basic principles. Good financial advisors can give you extraordinary value by guiding you in what economists know to be true about investing, taxation, and finance and, most importantly, by using that knowledge for your benefit rather than that of their own.

It is worth noting that investment advice and financial advice are not at all the same thing. Financial advice concerns the entire range of economic issues facing your family, now and into the future. Investment advice, on the other hand, is a small subset of that. Investment advice alone is deeply inadequate as a means of planning one’s financial future. With that said, though, let’s think about investment guidance.

Economic science knows a great deal about investing, markets, and what actions an investor should take. By extension, highly trained economists have tremendous insight into what financial talk is nonsense, reflects nothing but random chance, or is dishonest. Using established economic facts as a polestar in financial decision making is one of the smartest things you can do. I am indebted to Apollo Lupescu, Ph.D., of Dimensional Fund Advisors, for suggesting the term evidence-based investing.

Among the ways that evidence-based guidance can help you are diversifying fully, avoiding excessive risk, understanding how markets actually work, changing investments efficiently, and holding costs to an absolute minimum. Beyond these, a skilled advisor can create tremendous value by optimizing the tax consequences of how you invest.

Among the ways that evidence-based guidance can help you are diversifying fully, avoiding excessive risk, understanding how markets actually work, changing investments efficiently, and holding costs to an absolute minimum. Beyond these, a skilled advisor can create tremendous value by optimizing the tax consequences of how you invest.

Taking advantage of the various preferences and pitfalls in the tax code can often put even more money into your pocket than excellent investment advice.

Most valuable of all, a worthwhile financial advisor can offer help in avoiding the excessive costs, bad ideas, scams, and “gotchas” that seem endemic in the financial arena. Perhaps because there is so much money at stake, there is no shortage of terrible advice. Robert J. Shiller and George A. Akerlof, both Nobel Prize-winning economists and authors, argue that as long as it is profitable, sellers will systematically exploit lack of knowledge and psychological vulnerabilities. Markets are not solely the bringers of material wealth and the greater good, say Shiller and Akerlof, they are also inherently filled with “tricks and traps and will ‘phish’ us as ‘phools.’”

The best financial advisors can deliver extraordinary value by using their superior knowledge, training, and diligence to steer us away from the promises of easy money and the very human inclination to make decisions by gut instinct. They must point like a laser at what economic science knows to be true. And if they will do all this as true professionals, with their sole intentions focused on what advances your best interests without being swayed by their own desires or needs, then they will truly be worth their weight in gold.

Why the FDA Is Bad News for Cancer Patients

Cancer patients with precious little time need answers, but the FDA restricts and obstructs research, says the former head of the National Cancer Institute.

Illustration by Gwenda Kaczor

When I left the National Cancer Institute (NCI), I was proud of what I had done to reshape it into an organization capable of managing the war on cancer. But one challenge had eluded me: I was unable to persuade the administrators at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to change the way they reviewed new cancer drugs. What might work when it came to a new diabetes drug or a cholesterol-lowering pill did not work for cancer drugs. The FDA’s failure to recognize this was impeding our progress. And patients who could have been saved were dying.

Admittedly, the FDA has the most difficult job of all government agencies. Whatever it does, it receives a barrage of criticism. The world outside the FDA seems to be split into two groups. The first includes the many lawyers, doctors, and activists who want every aspect of our food and our drugs to be examined in fine detail before being approved so that we can eliminate as many potential risks as possible. The second group again includes lawyers, doctors, and activists, but this group holds that new drugs are too tightly regulated and that we should relax regulations so we can get potentially lifesaving drugs to patients sooner. Many members of this second group also believe that what we eat is none of the FDA’s business.

If the FDA approves drugs rapidly, it angers the first group. If the FDA approves them too slowly, it angers the second. Of course, both groups have taken things too far. Most of us recognize that we need regulations; we don’t want the FDA to go away. But we do want it to get out of the way. We need some regulations, but we don’t need all that we have now.

Here’s an example of what I mean: aspirin, one of our truly miracle drugs. In its early testing, it produced adenomas (small benign tumors) in the lungs of mice. Nothing like that has been seen in humans, but if aspirin were being developed today, the presence of adenomas might prevent the pill’s approval. Aspirin, like all drugs, has some risks, but that doesn’t mean we should take it out of patients’ hands.

The FDA has brought criticism on itself by seeking (and getting) more and more control over our lives. Twenty-five percent of every dollar we spend in the United States goes to a product regulated by the FDA. The agency has more authority and control over our lives than almost any other government agency. Yet it still wants more.

Purchase the digital edition for your iPad, Nook, or Android tablet:

To purchase a subscription to the print edition of The Saturday Evening Post:

Kids Need More Time Outdoors

America was still mired in the Depression when my family moved into the south Los Angeles neighborhood of 61st Street, just east of Main Street, which was characterized by peaceful stillness, interrupted in the afternoons and on weekends by the shouts of children at play. My brother Raul and I were 5 and 7 when we moved into that house, oblivious to the difficulties facing the nation.

On the contrary, we felt blessed by the abundant opportunities to explore nature in our new home, even as it stood in the middle of the big city. A bedraggled yucca plant stood in the middle of our front yard, besieged by crabgrass. Even there we found things to study up close and wonder at — the grasshoppers that hopped in during the summer months and the bright yellow dandelions that grew there in profusion. When the dents-de-lion went to seed, they became translucent globes that we held up and blew at to watch their tiny filaments fly off into the air and disappear.

Our summers provided endless opportunities for exploration, as well as a challenge for us to entertain ourselves on days that languidly stretched themselves ever longer.

In the heat of summer nights, as we sat in the front room, we heard loud pinging at the front door — hard-shelled June bugs that, attracted by the house lights, came crashing against the screen. We learned to coddle ladybugs and recite to them the verse that urged them to fly away home because their house was on fire.

Once in a great while, we saw turtles that we suspected were brought in from the desert and had wandered away from their keepers’ homes. We fed them lettuce leaves and looked on as they munched on them. Many were the times, especially when intense summer heat made staying indoors intolerable, when we played outside well into the night, our child sounds competing with the chirping of the crickets.

Nights in Los Angeles were very dark then, and the stars shone brightly. The sight of shooting stars was not uncommon in the era before we became a megalopolis. Occasionally, the darkness was pierced by enormous shafts of light that moved dramatically across the sky, from searchlights placed in front of a market or a carpet store announcing a grand opening. Or a movie premiere.

When the war came, I was in fifth grade. The nights became even darker, as blackouts were ordered to hide us from marauding Japanese planes. Several times, we heard the nighttime wailing of sirens that announced a practice air raid drill and alerted residents to prepare their windows with blackout curtains.

But for the most part, the real world didn’t intrude much in this realm where we were free to be children, even older siblings like me who were genetically programmed toward seriousness. Raul and I did a lot of digging and playing with dirt in our backyard. We spent many days on our knees, inspecting the legions of red ants that entered and exited holes they had dug in the ground. I’m not proud to confess that, like boys before and after us, we indulged in macabre experiments on the poor ants, involving a magnifying glass and concentrated sunrays. Enough said on that.

Digging in dirt was great fun. We flooded an area with water from the garden hose and ran it through little ditches we had dug, damming the water up at intervals with pieces of wood we half buried in the muck. We made little paper boats and sailed them down our boy-made rivers.

But the best way we used our dirt paradise was as a spot for playing a game at which we spent countless hours — marbles. Ernie, my friend from across the street, often joined us. Playing in dirt got us very dirty. We tried to avoid kneeling in the dirt by squatting, which didn’t work at all. We wore overalls, like the ones worn by farmers and garage mechanics, and canvas tennis shoes.

With a stick, we traced a large circle in the dirt and, in its center, placed several marbles that formed the pot we would play for. That is, assuming we were playing “for keeps.”

The boy whose marble stopped closest to a line drawn in the dirt played first. The shooter selected a spot on the circle and, forming a fist with his shooting hand, he knuckled down to play. With his thumb, he propelled a marble toward the pot with the aim of knocking one or more of the marbles out of the ring. He pocketed the ones he knocked out and earned another shot. If the shooter was very good, he could continue until all the marbles were knocked out.

We’d play for countless hours, so many that the fingernails of our right, shooting thumbs developed holes from the pressure of the hundreds of marbles they had propelled.

Marbles and other games taught us the importance of playing by the rules. Arguments occurred when a player insisted on not conforming to them. Ernie’s father, an otherwise extremely mild-mannered man, came over to our house one evening demanding of our parents, for Pete’s sake! the return of his son’s marbles. Losing one’s marbles was not a good thing, then or now.

In summertime, we’d also play a lot of tag with other neighborhood kids, as well as hide-and-seek. The cry of “olly olly oxen free” rang out, signaling the all clear when hiders could emerge from their hiding places. After Frankenstein became a cinematic sensation, the child who was “it” became the monster. The mere thought that a monster was on the hunt for us was chilling, even though we knew it was only a boy or a girl.

On hot summer days, the iceman from Kirker Ice Company made his customary rounds. While he was out of sight, lugging a block of ice into our house for the ice box, children clustered around the back of his truck, packed floor-to-ceiling with ice, and engaged in a harmless but refreshing bit of thievery, helping ourselves to shards of ice that remained on the damp truck bed.

We had roller skates that we fitted over our shoes and tightened against the leather sole. A neat little metal key did the tightening. We skated only on the sidewalk. I never got the hang of braking so I just headed onto the grass until I stopped moving.

Police radio dramas and cowboy movies were popular at the time, and boys liked to wear badges. We made our own. The metal caps of soft drink bottles were lined with cork that we pried out. Then we held the metal cap on the outside of our shirts and pushed the cork into the cap from the inside. The cap stayed put. We became walking advertisements for soft drinks, including that new drink, Dr. Pepper. We wore holster sets that handled two pistols — the large, silver-colored ones being the most popular. Some boys had BB guns that actually shot steel or lead pellets. We didn’t. Mother considered them dangerous and beyond the pale.

Flying kites was fun, too. Raul was much better than I at maneuvering a kite, running to get it airborne and flying like a good kite should. Mine had a maddening tendency to fly in frustrating circles. And then crash.

On especially hot days, we made use of the garden hose and sprinkler that we set in the middle of the lawn. Other neighborhood children would join in as we frolicked around in our bathing suits through the fountain of cool water the sprinkler created for us. Loose grass and weeds and little twigs stuck to the bottoms of our feet.

When you’re 10, your summer is one big block of freedom to be a kid. When it’s 4:18 p.m. in the middle of July and you’re scraping those twigs off your feet and laughing with your friends, the life ahead of you is one of infinite possibility. Mostly, all things, starting with your own imagination, just seem wondrously infinite. I worry that kids today aren’t allowed such space.

As we grew older, the summers got shorter, and our playtime scarcer, until it all became a sepia-tinted memory in a life full of purpose, work, and seriousness.

But that’s another story.

Originally published at Zócalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org)

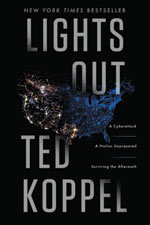

Lights Out!

Darkness.

As power shuts down, there is darkness and the sudden loss of electrical conveniences. As batteries lose power, there is the more gradual failure of cellphones, portable radios, and flashlights.

Emergency generators provide pockets of light and power, but there is little running water anywhere. In cities with water towers on the roofs of high-rise buildings, gravity keeps the flow going for two, perhaps three days. When this runs out, taps go dry; toilets no longer flush. Emergency supplies of bottled water are too scarce to use for anything but drinking, and there is nowhere to replenish the supply. Disposal of human waste becomes a critical issue within days.

Supermarket and pharmacy shelves are empty in a matter of hours. The city has flooded the streets with police to preserve calm, to maintain order, but the police themselves lack critical information. There is a growing awareness that this power outage extends far beyond any particular city and its suburbs. It may extend over several states. Tens of millions of people appear affected. The assumption that the city, the state, or even the federal government has the plans and the wherewithal to handle this particular crisis is being replaced by the terrible sense that people are increasingly on their own. When that awareness takes hold, it leads to a contagion of panic and chaos.

Preparing for doomsday has its own rich history in this country, and predictions of the apocalypse are hardly new. We lived for decades with the assumption that nuclear war with the Soviet Union was a real possibility. Ultimately, Moscow and Washington came to the conclusion that mutual assured destruction, holding each other hostage to the fear of nuclear reprisal, was a healthier approach to coexistence than mass evacuation or hunkering down in our respective warrens of bomb shelters in the hopes of surviving a nuclear winter.

We are living in different times. Whether the threat of nuclear war has actually receded or we’ve simply become inured to a condition we cannot change, most of us have finally learned “to stop worrying and love the bomb.” In reality, though, the ranks of our enemies, those who would and can inflict serious damage on America, have grown and diversified. So many of our transactions are now conducted in cyberspace that we have developed dependencies we could not even have imagined a generation ago. To be dependent is to be vulnerable. We have grown cheerfully dependent on the benefits of our online transactions, even as we observe the growth of cyber crime. We remain largely oblivious to the potential catastrophe of a well-targeted cyberattack.

On one level, cyber crime is now so commonplace that we have already absorbed it into the catalogue of daily outrages that we observe, briefly register, and ultimately ignore. Over the course of less than a generation, cyber criminals have become adept at using the Internet for robbery on an almost unimaginable scale. Still, despite the media attention generated by the more dazzling smash-and-grab operations, the cyber criminals whose only intention is to siphon off wealth or hijack several million credit card identities should have a lower priority among our concerns. Their goal is merely grand larceny.

More worrisome is the increasing number of cyberattacks designed to vacuum up enormous quantities of data in what appear to be wholesale intelligence-gathering operations. The most ambitious of these was announced on June 4, 2015, and targeted the Office of Personnel Management, which handles government security clearances and federal employee records. The New York Times quoted J. David Cox Sr., the president of the American Federation of Government Employees, as saying the breach might have affected “all 2.1 million current federal employees and an additional 2 million federal retirees and former employees.” FBI director James Comey told a Senate hearing that the actual number of hacked files was likely more than 10 times that number — 22.1 million. Government sources were quoted as claiming that the intrusion originated in China. The Times report raises a number of relevant issues: The probe was initiated at the end of 2014. It wasn’t discovered until April of 2015. It is believed to have originated in China, but the Chinese government has denied the charge, challenging U.S. authorities to provide evidence. Producing evidence would reveal highly classified sources and methods. “The most sophisticated attacks,” the Times noted, “often look as if they were initiated inside the United States, and tracking their true paths can lead down many blind paths.” All of these issues will receive further attention in later chapters. But as disturbing as these massive data-collection operations may be, even they do not come close to representing the greatest cyber threat. Our attention needs to be focused on those who intend widespread destruction.

The Internet provides instant, often anonymous, access to the operations that enable our critical infrastructure systems to function safely and efficiently. In early March 2015, the Government Accountability Office issued a report warning that the air traffic control system is vulnerable to cyberattack. This, the report concluded with commendable understatement, “could disrupt air traffic control operations.” Our rail system, our communications networks, and our healthcare system are similarly vulnerable. If, however, an adversary of this country has as its goal inflicting maximum damage and pain on the largest number of Americans, there may not be a more productive target than one of our electric power grids.

Electricity is what keeps our society tethered to modern times. There are three power grids that generate and distribute electricity throughout the United States, and taking down all or any part of a grid would scatter millions of Americans in a desperate search for light, while those unable to travel would tumble back into something approximating the mid-19th century. The very structure that keeps electricity flowing throughout the United States depends absolutely on computerized systems designed to maintain perfect balance between supply and demand. Maintaining that balance is not an accounting measure, it is an operational imperative. The point needs to be restated: For the grid to remain fully operational, the supply and demand of electricity have to be kept in perfect balance. It is the Internet that provides the instant access to the computerized systems that maintain that equilibrium. If a sophisticated hacker gained access to one of those systems and succeeded in throwing that precarious balance out of kilter, the consequences would be devastating. We can take limited comfort in the knowledge that such an attack would require painstaking preparation and a highly sophisticated understanding of how the system works and where its vulnerabilities lie. Less reassuring is the knowledge that several nations already have that expertise, and — even more unsettling — that criminal and terrorist organizations are in the process of acquiring it. Our media report daily on increasingly bold and costly acts of online piracy that are already costing the U.S. economy countless billions of dollars a year. Cyberattacks as instruments of national policy, though, tend to be less visible because neither the target nor the attacker is inclined to publicize the event.

NASA/Shutterstock

History often provides a lens through which irony comes into focus. The United States, for example, was the first and only nation to have used an atomic weapon, and it has spent the intervening decades trying to limit nuclear proliferation. And the United States, in collaboration with Israel, mounted a hugely successful cyberattack on Iran’s nuclear program in 2008 and now finds itself dealing with the consequences of having been the first to use a digital weapon as an instrument of policy. Iran wasted little time in launching what appeared to be a retaliatory cyberattack, choosing to target Aramco in Saudi Arabia, destroying 30,000 of its computers. Why the Saudi oil giant instead of an American or Israeli target? We can only speculate. Iran may have wanted to issue a warning, demonstrating some of its own cyber capabilities without directly engaging the more dangerous Americans or Israelis. In any event, Iran made its point, and a new style of warfare has, within a matter of only a few years, become commonplace. Russia, China, and Iran, among others, continue on an almost daily basis to demonstrate a range of cyber capabilities in espionage, denial-of-service attacks, and the planting of digital time bombs capable of inflicting widespread damage on a U.S. power grid or other piece of critical infrastructure.

For several reasons, the clear logic of a swift attack and response that enables a policy of deterrence between nuclear rivals does not yet exist in the world of cyber warfare. For one, cyberattacks can be launched or activated from anywhere in the world. The point at which a command originates is often deliberately disguised so that its electronic instruction appears to be coming from a point several iterations removed from its actual location. It is difficult to retaliate against an aggressor with no return address. Nation-states may be inhibited by the prospect of ultimately being unmasked, but it is not easily or instantly accomplished. For another, the list of capable cyberattackers is far more numerous than the current list of the world’s nuclear powers. We literally have no count of how many groups or even individuals are capable of launching truly damaging attacks on our electric power grids — some, perhaps even most of them, uninhibited by the threat of retaliation.

There is scant consolation to be found in the fact that a major attack on the grid hasn’t happened yet. Modified attacks on government, banking, commercial, and infrastructure targets are already occurring daily, and while sufficient motive to take out an electric power grid may be lacking for the moment, capability is not. As the ranks of capable actors grow, the bar for cyber aggression is lowered. The unintended consequences of Internet dependency are already piling up. Prudence suggests that we at least consider the possibility of a cyberattack against the grid, the consequences of which would be so devastating that no administration could consider it anything less than an act of war.

Ours has become a largely reactive culture. We are disinclined to anticipate disaster, let alone prepare for it. We wait for bad things to happen and then we assign blame. Despite mounting evidence of cyber crime and cyber sabotage, there appears to be widespread confidence that each can be contained before it inflicts unacceptable damage. The notion that some entity has either the ability or the motive to launch a sophisticated cyberattack against our nation’s infrastructure, and in particular against our electric power grids, exists, if at all, on the outer fringes of public consciousness. It is true that unless and until it happens, there is no proof that it can; for now, what we are left with, for better or worse, is the testimony of experts. There will be more than a few who take issue with the conclusions of this reporter that the grid is at risk. But the book from which this article is taken reflects the assessment of those in the military and intelligence communities and the academic, industrial, and civic authorities who brought me to the conclusion that it is.

Widespread recognition of the vulnerability of our power grids already exists. Lots of smart people are already offering partial remedies and grappling with solutions. But there is not yet widespread recognition that we have entered a new age in which we are profoundly vulnerable in ways that we have never known before, and so there is neither a sense of national alarm nor the leadership to take us where we need to go. Our national leaders are in a precarious place. They recognize the scale of danger that a successful cyberattack represents. However, portraying it too graphically without having developed practical solutions runs the obvious risk of simply provoking public hysteria.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created in an atmosphere of national trauma. The world’s greatest superpower was made to realize its vulnerability to a handful of men armed with box cutters. We remain distracted to this day by the prospects of retail terrorism when we should be focused on the wholesale threat of cyber catastrophe. In such an event, the Department of Homeland Security would be working with industry to help them restore and maintain service. It should be focused on developing a more robust survival and recovery program for the general public; but DHS has neither the capacity to defend our national infrastructure against cyberattack nor the wherewithal with which to retaliate. A criminal attack would be the responsibility of the FBI; an attack on infrastructure by a nation-state or a terrorist entity would become the immediate responsibility of the Defense Department. Anticipating and tracking external cyber threats to U.S. infrastructure should be, by virtue of capability if nothing else, the responsibility of the NSA.

Limits that were established in a different era still exist on paper, but they are eroding in practice. The CIA is precluded, by law, from operating within the United States, but maintaining national boundaries in cyberspace may be impossible. Cyber Command is a military operation tasked with organizing the defense of U.S. military networks. The extent to which it can participate in the defense of critical infrastructure within the United States remains murky, but sidelining critical U.S. defense capabilities because we haven’t quite adapted to the notion that a major cyberattack can be as devastating as an invasion makes no sense.

The imposition of order, the distribution of essential supplies, the establishment of shelters for the most vulnerable, the potential management of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of domestic refugees will be complex enough if the general public knows what to expect and what to do. In the absence of any targeted preparation, in the absence of any serious civil defense campaign that acknowledges the likelihood of such an attack, predictable disorder will be compounded by a profound lack of information. It would be the ultimate irony if the most connected, the most media-saturated population in history failed to disseminate the most elementary survival plan until the power was out and it no longer had the capacity to do so.

There is, as yet, no real sense of alarm attached to the prospect of cyber war. The initial probes — into our banks and credit card companies, into newspapers and government agencies — have tended to leave us unmoved. Past experience in preparing for the unexpected teaches us that, more often than not, we get it wrong. It also teaches that there is value in the act of searching for answers. Acknowledging ignorance is often the first step toward finding a solution. The next step entails identifying the problem.

Here it is: For the first time in the history of warfare, governments need to worry about force projection by individual laptop. Those charged with restoring the nation after such an attack will have to come to terms with the notion that the Internet, among its many, many virtues, is also a weapon of mass destruction.

Crown Publishers

Adapted from Lights Out: A Cyberattack, a

Nation Unprepared, Surviving the Aftermath, Copyright © 2015 by Ted Koppel. Published by Crown Publishers, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

November/December 2015 Limerick Laughs Winner and Runners-Up

Right now I am seeking assurance

As I start on this test of endurance.

It’s not that I fear

Falling hard on my rear;

It’s worry about my insurance!

—Adele Suga, Vassalboro, Maine

Congratulations to contest-winner Adele Suga! For her limerick describing the George Hughes illustration Ice-skating Class for Dad (above), Adele wins $25 and our gratitude for an entertaining poem. If you’d like to enter the Limerick Laughs Contest for our next issue of The Saturday Evening Post, submit your limerick via our online entry form.

Adele’s limerick wasn’t the only one we liked. Here are some of our other favorite contest entries, in no particular order:

This awkward young dad’s in a bind,

But his teachers are patient and kind.

He’s learning a skill

With a slippery drill

That will yield a most sore behind!—Rose Hester, Brooklyn, New York

He thought he would gracefully glide;

Instead he did clumsily slide.

With his offspring at hand,

He was able to stand,

So all that he hurt was his pride.—Carolyn Tourville, Tullahoma, Tennessee

We didn’t just go ’cause we HAD to …

To skate with our Dad, we were GLAD to.

“You kids will do great

Once I teach you to skate!”

But we ended up teaching our DAD to.Our Dad enjoys making the case

That skating is all about grace:

“It’s rhythmic, poetic,

Refined and aesthetic…”

HEY, DAD JUST FELL FLAT ON HIS FACE!!!—Guy Pietrobono, Washingtonville, New York

On Wall Street, a respected CO.

On the ice … he just couldn’t go.

With some slides and some slids,

Even help from his kids,

He always ended up in the snow!—Marlayne Jackson, New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

When it came to outdoorsy-type stuff,

My dad liked things rugged and rough.

But when it was icy,

Things got a bit dicey.

It turned out he wasn’t so tough.—Neal Levin, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

“That looks so easy,” he cried.

“I got this — shuffle and glide.”

Now Dad’s steering is errant,

His lost balance apparent.

Here comes a THUD to his pride.—Dan Rogers, Garland, Texas

The Wonderful World of Dr. Seuss

In the summer of 1957, Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, had just published a children’s primer called The Cat in the Hat, and his newest story, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, was ready for publication later that year. It was during this interlude that Geisel granted his first Post interview with Robert Cahn, revealing why he became Dr. Seuss, the simple reason he draws the way he does, and the undeniable effect his wife, Helen, has had on his career.

The Wonderful World of Dr. Seuss

By Robert CahnJuly 6, 1957 — Theodor Geisel, alias Dr. Seuss, has captured the imagination of millions of children with his fanciful spoofs: Gerald McBoing-Boing, the Drum-Tummied Snumm, and other creatures from a world of happy nonsense.

For a man whose mind is inhabited by such creatures as a Mop-Noodled Finch, a Salamagoox, or a Bustard — “who only eats custard with sauce made of mustard” — Theodor S. Geisel looks disarmingly rational. As the renowned Dr. Seuss (rhymes with “goose”), he is not, as a few children have pictured him, a wizened old man with flowing white beard. He is whiskerless, has the standard number of arms and legs, and lives quietly with his wife and dog on a hill overlooking La Jolla, California.

Yet for the past thirty years, under the protective alias of Dr. Seuss, Ted Geisel has been an apostle of joyous nonsense. He has fathered a whole modern mythology of bizarre creatures like the Remarkable Foon, “who eats sizzling hot pebbles that fall off the moon,” or the Drum-Tummied Snumm, “who can drum any tune that you might care to hum—doesn’t hurt him a bit ’cause his drum-tummy’s numb.” He has created young Gerald McBoing-Boing, the little boy who cannot speak, but makes sound effects instead. And he is still remembered for the impertinent bugs he concocted along with his famous advertising slogan: Quick, Henry, the Flit!

His annual output of picture books, like Horton Hatches the Egg, Thidwick the Big- Hearted Moose, and On Beyond Zebra, have become a part of the basic children’s literature of the country. They are in constant use at the overseas libraries of the United States Information Agency and have been translated into several foreign languages, including Japanese.

In suburban La Jolla, however, Geisel’s madcap alter ego is completely obscured. Here Theodor Seuss Geisel — Seuss is his mother’s family name — is considered a paragon of propriety. He is a director of the town council, and a trustee of the neighboring San Diego Fine Arts Gallery. His hair is cut regularly, his shoes are always shined, and he gives up his chair when ladies are standing.

The first impression of conservatism is emphasized by his polite attentiveness, not unlike that of a middle-aged bank vice president. Slim and tall, he has graying dark hair parted more or less in the middle. He is as sharp-eyed as a bird, with a long aquiline nose and a wide mouth which has a habit of twisting into puckish grins. And he speaks in the terse hesitancies of the painfully shy man.

But beneath this outer austerity beats a wildly impulsive heart. Even with the most serious intentions, the mind of Ted Geisel is so fanciful that he has never been able completely to subdue it. And he depends at all times on the levelheadedness of his wife, Helen, to pull him out of entanglements in which he has become errantly involved. Yet the unorthodox appearance of the Seuss animals is not entirely due to Geisel’s imagination. The fact is, as Geisel admits, “I just never learned to draw.”

“Ted never studied art or anatomy,” explains Helen. “He puts in joints where he thinks they should be. Elbows and knees have always especially bothered him. Horton is the very best elephant he can draw, but if he stopped to figure out how the knees went, he couldn’t draw him.”

Although the greatest audience for his animals is children, the nonsensical creatures are also in great demand among advertisers seeking a humorous presentation for their products. Sometimes, however, his business clients have lacked the willing imagination of his younger devotees. Once he had to do a horned goat for a billboard. The job was done and paid for, and everyone seemed happy, when the phone rang.

“Now, Geisel, about that goat,” said the advertising-agency executive. “We like it here and it’s a fine goat, but there is just one little thing wrong. Our client thinks it looks like a duck. So would you mind doing us another one?”

To resolve the problem, Geisel drew a duck and submitted it. The client called him up. “Geisel,” he said, “it’s perfect. Best goat I ever saw.”

Children, of course, understand and accept Geisel’s pictures, a fact which led to an unusual assignment two years ago during the height of the controversy over why Johnny can’t read. Textbook publishers and some educators and parents had realized that one trouble was that Johnny’s reader wasn’t readable. Most creators of children’s primers, though experts in form, failed miserably as storytellers. What was required, the publishers knew, was the kind of story that would lead a child from page to page with suspense and delight. Yet most writers were unwilling to accept the severe vocabulary limitations required for a first-grade reader.

Into the impasse stepped Geisel. He offered his services to one of the nation’s leading textbook publishers and was assigned to prepare a book that six-year-olds could read themselves. Unfortunately, the situation soon got out of hand.

“All I needed, I figured, was to find a whale of an exciting subject which would make the average six-year-old want to read like crazy,” says Geisel. “None of the old dull stuff: Dick has a ball. Dick likes the ball. The ball is red, red, red, red.”

His first offer to the publisher was to do a book about scaling the peaks of Everest at sixty degrees below zero.

“Truly exciting,” the publisher agreed. “However, you can’t use the word scaling, you can’t use the word peaks, you can’t use Everest, you can’t use sixty, and you can’t use degrees.

Geisel shortly found himself with a list of 348 words, most of them one-syllable words, which the average six-year-old could recognize — and not a Yuzz-A-Ma-Tuzz or Salamagoox among them. To one who was used to making up new words at will, it was a catastrophe. And yet the publisher had said, “Create a rollicking carefree story packed with action and tingling with suspense.”

Six months after accepting the assignment, Geisel was still staring at the word list, trying to find some words besides ball and tall that rhymed. The list had a daddy, but it didn’t have a caddy. It had a thank, but it had no blank, frank, or stank. Page after page of scrawls was piled in his den. He had accumulated stories which moved along in fine style but got nowhere. One story about a King Cat and a Queen Cat was half finished before he realized that the word queen was not on the list.

One night, when he was almost ready to give up, there emerged from a jumble of sketches a raffish cat wearing a battered stovepipe hat. Geisel checked his list—both hat and cat were on it. Gradually he worked himself out of one literary dead end after another until he had completed his children’s reader.

The Cat in the Hat was published last spring by Houghton Mifflin as a supplementary school text for first graders, and in a popular edition by Random House. It already has been greeted enthusiastically by parents and educators. The story line concerns fanciful adventures occurring when a vagrant cat drops in to play with two small children while their mother is out. The verse, composed from only 220 different basic words, has a delightful meter and builds repetitions through devices such as the cat adding object after object to a juggling act. And the drawings, of course, are pure Seuss.

Although the principal character of The Cat in the Hat turns out all right in the end, he is not quite in keeping with most Seuss animals, which are usually gentle, loving, and true blue. Horton, for instance, is a long-suffering elephant who sits on the egg of Mayzie the Lazy Bird through 12 trouble-filled months. And Thidwick is a moss-munching moose who is victimized by an inconsiderate assortment of freeloading friends nesting in his antlers.

“Ted’s animals are the sort you’d like to take home to meet the family,” says Helen. “They have their own world and their own problems and they seem very logical to me.”

Ted first met Helen Palmer in 1925, at Oxford. Young Geisel was studying English literature, seeking a doctor’s degree so that he could qualify for the faculty at Dartmouth, his alma mater. In one of his classes, he found himself sitting next to an attractive young schoolmarm-to-be who kept admiring the flying horses he doodled in the margin of his notebook.

“I was naturally flattered,” says Geisel, “and in a short time the horses were taking up the middle of my notebook, and my Shakespeare notes — such as they were — were in the margins.”

Within a year, Helen Palmer and Theodor Geisel were engaged. Aware that Ted loved drawing better than studying Shakespeare, Helen encouraged him to forsake temporarily his scholarship quest. In the spring of 1927, Geisel returned to his family home in Springfield, Massachusetts. For 10 weeks he drew cats, elephants, bears, and rejection slips. His family was not especially pleased that their son had junked a promising career as an educator in favor of concocting knock-kneed brown bears. On the other hand, Theodor Geisel, Sr., felt partly responsible. After all, as commissioner of parks in Springfield, he had long had a doting interest in the city zoo, where young Ted had often entered the lion cages, and had played with the kangaroos and cub bears.

Toward the end of the trial period, Geisel’s artistic talents finally were recognized when The Saturday Evening Post bought a cartoon for $25. Geisel moved to New York, sold a page of eggnog-drinking turtles to Judge, a humor magazine, and parlayed the fee into a grubstake for marriage.

It was not as Theodor Geisel that he first broke into print. Desiring to save his name for the great serious work he planned someday to write, he adopted aliases such as Quincy Quilp, Dr. Xavier Ruppzknoff, and Dr. Theophrastus Seuss.He finally settled on just plain Dr. Seuss.

It was an early Dr. Seuss cartoon published by Judge late in 1927 that abruptly changed his life. The cartoon showed a knight in bed, with armor strewn about the castle room and a dragon sticking his snout under the covers. It bore the caption, “By gosh, another dragon! And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit.”

The cartoon caught the eye of Mrs. Lincoln Cleaves, wife of a McCann-Erickson advertising executive who handled the Flit account for Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. For three weeks Mrs. Cleaves badgered her husband to contact this Dr. Seuss, whoever he was. Finally weakening, Cleaves agreed. Geisel was signed to a contract, and he quickly created the slogan, “Quick, Henry, the Flit.”

A major crisis arose early in the campaign. Some company officials felt the Seuss bugs looked so sweet and lovable that no one would want to use Flit to kill them. Geisel finally convinced the executives that this was just part of a scheme to overcome women’s natural reluctance to think about bugs. “Quick, Henry, the Flit” became a standard line of repartee in radio jokes. A song was based on it. The phrase became a part of the American vernacular for use in emergencies. It was the first major advertising campaign to be based on humorous cartoons.

But Geisel had to find additional outlets for the stream of his invention. For several years he built up his own fleet, the “Seuss Navy,” as a promotion for Standard Oil’s Essomarine products. He awarded honorary admirals’ commissions in the Seuss Navy to noted yachtsmen, steamship-line captains, and naval officers and presided over a yearly banquet for the group. The Seuss admirals even flew their own burgee—a plucked herring on blue field with red trim.

As an added outlet for his fancies, Geisel dreamed up devices to make a fortune. One scheme was for an “Infantagraph.” It was just before the opening of the New York World’s Fair, when everyone was thinking of ways to make money from the out-of-towners who would swarm out to Flushing Meadows. Musing over these vistas of dollar bills, Geisel envisioned a booth on the midway with a huge sign: IF YOU WERE TO MARRY THE PERSON YOU ARE WITH, WHAT WOULD YOUR CHILDREN LOOK LIKE? COME IN AND HAVE YOUR INFANTAGRAPH TAKEN. Certainly this come-on should bring couples into the booth in droves. There they would be photographed, and out would come a composite picture of their features on a naked baby sprawled on a white bearskin rug.

All that was necessary was to devise a camera which could do the trick. Geisel acquired financing and brought a German camera technician to New York from Hollywood. A camera was built. Tests showed that the project was feasible. However, there were many problems, especially in preventing a mustache from coming through on the baby’s picture. They couldn’t perfect the camera while the fair was on, and the enterprise terminated when the war prevented importation of special lenses from Germany.

“It was a wonderful idea,” Geisel says. “Somehow, though, all the babies tended to look like William Randolph Hearst.”

Yet out of the restlessness of the Flit days, there came a rewarding byproduct. Trying to while away the hours on a long, rough Atlantic crossing in 1937, Ted began composing verses to the rhythm of the Kungsholm’s pulsing engines. “Ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da,” went the engines. “And that is the story that no one can beat,” wrote Geisel. “Ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da,” went the ship. “If I say that I saw it on Mulberry Street.”

“My contract had nothing to prohibit my writing children’s books,” says Geisel. “When we docked in New York, instead of going to a psychiatrist to get that crazy rhythm out of my head, I decided to illustrate the verses for a children’s book.” After turndowns from several publishers, Geisel interested Marshall (Mike) McClintock, a Dartmouth classmate who was working for Vanguard Press. Vanguard decided to take a chance, and in 1937 published And To Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street.

Mulberry Street, which relates how a little boy lets his imagination run loose while walking home from school, is today in its 11th printing. It is still in demand at bookstores and libraries, although it must now compete with 12 other Seuss picture books.

Three of them —The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The King’s Stilts, and Bartholomew and the Oobleck — are in prose and have sometimes been compared to the stories of Hans Christian Andersen.

In all his books, Dr. Seuss starts out with a premise so believably fantastic that what follows seems entirely logical. Thus, in On Beyond Zebra, once you admit that the alphabet can extend beyond Z, it follows that the letter Um is for spelling Umbus:

A sort of a cow, with one head and one tail,

But to milk this great cow you need more than one pail!

She has ninety-eight faucets that give milk quite nicely.

Perhaps ninety-nine. I forget just precisely.

And, boy! She is something most people don’t see

Because most people stop at the Z

But not me!The all-time Seuss favorite is Horton Hatches the Egg, which in 1956 sold 15,000 copies, three times as many as when first published in 1940. Horton, a loyal, lovable elephant, gets conned by Mayzie the Lazy Bird into hatching her egg. Horton sits and sits and sits, though ridiculed by friends, frozen by cold, captured by hunters, and finally sold to a circus. When Mayzie returns to claim the egg, just as it starts hatching, it seems that Horton’s faithfulness will go unrewarded. But wait! Coming out of the egg and flying over to Horton is an Elephant-Bird, with ears and tail and a trunk just like his.

And it should be, it should be, it SHOULD be like that!

Because Horton was faithful! He sat and he sat!

He meant what he said and he said what he meant

And they sent him home happy, one hundred per cent.Soon after his first book had been published, the demands on a successful author brought Ted Geisel face to face with a long-standing dread of making public appearances. He was then living in New York and he casuallyagreed to speak at a young women’s college in Westchester, thinking he had ample time to contrive an excuse to get out of it. Unfortunately he forgot the engagement until too late to break it. When Helen insisted that he live up to his agreement, he pleaded sudden illness to no avail. Finally he departed. A couple of hours later, the school called to inquire what was keeping Mr. Geisel. Alarmed, Helen instituted a search. She called his publisher, his friends, then hospitals, but he was nowhere to be found. When Geisel finally returned home, it was discovered that instead of taking the train to Westchester he had hidden out all afternoon at Grand Central Station.

As happens sooner or later with most writers, Geisel has had hit-and-run encounters with Hollywood. During the war, he was an officer with Frank Capra’s educational-film unit and won the Legion of Merit for helping to produce and direct indoctrination films. Shortly after the war, he teamed with Helen to write a screenplay about the rise of the war lords in Japan. The picture, Design for Death, won the 1947 Academy Award for the best feature-length documentary.

In 1951, Geisel created the character of Gerald McBoing-Boing. Young Gerald, whose first words were boing, boing instead of da-da or ma-ma, was originally written for a phonograph record as a satire on parents who fear that slowness in learning to speak indicates a child is dimwitted. The movie cartoon of Geisel’s story won an Academy Award for U.P.A. — United Productions of America — and for Gerald a place in the folklore of America.

In La Jolla, Ted Geisel, citizen, far outranks Dr. Seuss, artist and writer. In addition to his work on the town council and with the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery, he has a special interest. This is to protect La Jolla from Creeping Urbanization. When Ted and Helen Geisel went to La Jolla in 1940, it was a quiet village mostly populated by the wealthy and retired. They bought an old tower on the highest hill and built a house around it. Then came the burgeoning growth of Southern California. Soon they found themselves in the landing path of jet planes, while the town below was invaded by big spenders. A pox of garish neon lights began to blight the community.

While he could not stop the tourist invasion or the jet planes, Geisel has been the prime mover in a campaign to ban commercial billboards and objectionable signs in La Jolla. He even enlisted Dr. Seuss to do an illustrated booklet. In it, two competitive cave men, Guss and Zaxx, engaged in a war to ballyhoo their products, Guss-ma-Tuss and Zaxx-ma-Taxx. Horrendous signs spring up all around, dwarfing their cave sites:

And, thus between them, with impunity

They loused up the entire community.

Sign after sign after sign, until

Their property values slumped to nil.

And even the dinosaurs moved away

From that messed-up spot in the U.S.A.In their tower, the Geisels have a relatively quiet oasis. Their two-acre spot is screened by hundreds of flowering shrubs. Inside the house, all is in perfect order except the den, where Ted spends hours at his drawing board. He loves to draw, but hates to write, and sometimes will spend hours just drawing animals on large sheets of tracing paper. Many of his books, he confesses, have had their start by accident. Horton Hatches the Egg came about because Geisel inadvertently superimposed an elephant over the branches of a small tree he had drawn earlier. So he worked for days trying to figure how Horton could have got into the tree. Then Helen had to figure out how to get Horton down.

The process of turning out a Seuss book is definitely a family affair. “I keep losing my story line and Helen has to find it again,” says Geisel. “She’s a fiend for story line.”

Once the basic idea is set, nearly every line is worked and reworked until both Ted and Helen are satisfied. Geisel’s workroom is always littered with swatches of verses pinned to sketches or taped to a large plate-glass window overlooking the ocean.

All business affairs are run by Helen. Checkbooks confuse Ted, who prefers to count only in large round numbers. Helen also tries to protect Ted from visitors, although in this area she is not always successful. At the slightest provocation, Geisel will halt his work and lead the visitor into the den, where he displays the sketches for his latest book and enthusiastically reads off the verses. There is little doubt that Ted Geisel is himself the first small child for whom he writes.

A few weeks ago, the Geisel household was in one of its “deadline-time-again” emergencies. As usual, Dr. Seuss was in trouble because Geisel couldn’t figure out an ending. He had started off with a wonderful idea — he would do a Christmas book. A bad old Grinch would try to stop Christmas from coming to Who-ville. The suspense had built panel by panel as the little Whos got all their gifts and trees and fixings ready while the Grinch plotted his devilish mission. Then came the stumbling block. How could he end it without being maudlin?

“Helen, Helen, where are you?” Geisel shouted, emerging from his den into the living room. “How do you like this?” he said, dropping a sketch and verse in her lap.

Helen shook her head. Geisel’s face dropped. “No,” she said, “this isn’t it. And besides, you’ve got the papa Who too big. Now he looks like a bug.”

“Well, they are bugs,” said Geisel defensively.

“They are not bugs,” replied Helen. “Those Whos are just small people.”

Geisel retreated to his den to fix the picture and try again with the verses. The dilemma was finally resolved, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas will be published this fall.

On occasion the mother of a young Dr. Seuss follower may wish that the author were less imaginative, especially if her eight-year-old has just ruined two dozen eggs while trying to make Scrambled Eggs Super-dee-Dooper. But most parents consider the Seuss books surefire bedtime stories and are pleased by the hidden gems of wisdom. In Horton Hears a Who, for instance, kind Horton protects the microcosmic inhabitants of a kingdom which exists on a dust speck — “For a person’s a person, no matter how small.” The Whos, about to be boiled in a Beezle-Nut stew because their voices cannot be heard by the outside world, are finally saved when a lone shirker adds his tiny “Yopp” to the united efforts of the citizenry.

And that Yopp, that one small, extra Yopp put it over!

Finally, at last! From that speck on that clover

Their voices were heard! They rang out clear and clean.

And the elephant smiled. “Do you see what I mean?”

They’ve proved they are persons, no matter how small.

And their whole world was saved by the smallest of all!“In our books there is usually a point, if you want to find it,” says Geisel. “But we have discovered that the kids don’t want to feel you are trying to push something down their throats. So when we have a moral, we try to tell it sideways.

Although the Geisels are childless, Ted long ago invented a daughter to vie with the progeny of their friends. Chrysanthemum-Pearl, to whom one of his books is lovingly dedicated, is a comfort to the Geisels, especially when the after-dinner conversation swings around to children and grandchildren. As might be expected, Chrysanthemum-Pearl is a precocious girl who has been able to “whip up the most delicious oyster stew with chocolate frosting and flaming Roman candles,” or who can “carry 1000 stitches on one needle while making long red underdrawers for her Uncle Terwilliger.”

Despite his label as a “children’s author,” Geisel refuses to write down to children. Because of this viewpoint, the Dr. Seuss books are enjoyed by the parents as well as the youngsters. And though contributors to the children’s-book field are often snubbed by the literati, Geisel finally received his reward. One June day in 1955, he was called back to the Dartmouth College commencement exercises.

“Theodor Seuss Geisel, creator of fanciful beasts,” the college president read from a scroll as Geisel walked to the front of the platform. “As author and artist you singlehandedly have stood as Saint George between a generation of parents and the demon dragon of exhausted children on a rainy day. You have stood these many years in the shadow of your learned friend, Dr. Seuss. But the time has come when the good doctor would want you to walk by his side as a full equal. Dartmouth therefore confers on you her Doctorate of Humane Letters.”

Occasionally these days, Doctor Geisel runs into someone who slaps him on the back and says, “Geisel, with all your education, you should be able to do better. There must be some way you could crack the adult field.”

Geisel raises an eyebrow, then smiles. “Write for adults?” he replies. “Why, they’re just obsolete children.”

This isn’t the only time Dr. Seuss has appeared in the pages of the Post. Find out more about him in “The Unforgettable Dr. Seuss.”

Fiction by Dalton Trumbo

Rooting for Bryan Cranston for the Oscar win? Before settling in to watch the 2016 Academy Awards, brush up on fiction by Dalton Trumbo (played by Best Actor nominee Cranston in Trumbo) from our archive:

“Darling Bill—” by Dalton Trumbo

April 20, 1935

A love-struck Congressman’s secretary sends an errant press release that leads to political corruption. “Darling Bill—” was the first story published in a series of political satire Dalton Trumbo wrote for magazines and film.

“Five C’s for Fever the Five” by Dalton Trumbo

November 30, 1935

A gambler uses his doppelganger to pull off a can’t-lose bet — or so he thinks.

“Darling Bill—” by Dalton Trumbo

Editor’s note: “Darling Bill—” was the first in a series of political satire Dalton Trumbo wrote for magazines and film. The epistolary fiction first appeared in The Saturday Evening Post on April 20, 1935.

OFFICE OF REPRESENTATIVE GEORGE W. BILCHESTER

DARLING BILL: Things have let up a minute, so maybe I’ll get a chance to write you. It isn’t that I don’t want to write oftener, honey. I just don’t get the time. Being secretary to Congressman Bilchester is no party. He is a gloomy old guy, as you must know from seeing him around Dubroc’s store at home so much, and he is always very much alarmed about what is going on here in Washington. He has been having what he calls his nervous stomach all morning about some silly statement to the press. So please excuse all the scratchings-out and misspellings you may find in this letter, because he has been hounding me and I’m so nervous I could just bawl. The thing that has upset him is the Sparling Bill, and I just know he’ll pop in right in the middle of this letter with some more old dictation about it.

Believe me, Bill, I sure wish I was back in Chillburg with you and Mom and Pop. Don’t you be blue about not getting a job. A young man with a fine engineering education like you is bound to get somewhere. If I can ever get old Bilchester cornered long enough, maybe I can talk him out of an appointment for you. But it seems the other side is building all the dams—a thing which I can tell you certainly does not help Mr. Bilchester’s stomach. He says it’s nothing but a scandal anyhow, and that he has a hard enough time getting a janitor appointed, much less somebody important like an engineer. And anyhow, a girl is so unimportant around here she hasn’t much chance to do anything but act dumb and take press statements.

Just a minute, sweet. Here he comes with his press release about the Sparling Bill. I’ll run it off and then finish this letter to you. Until then, darling—

PRESS STATEMENT, REPRESENTATIVE BILCHESTER,

re Federal extravagance:

“The country is being stampeded into insolvency,” declared Representative George W. Bilchester, minority keynoter, in his weekly press conference today. Pointing to billions being “poured into administration rat holes,” Rep. Bilchester reiterated his successful campaign cry of last November by declaring that “nobody is going to shoot Santa Claus, but the old man can be bled to death.”

Decrying Federal appropriations as “mass buying of votes equaled only in decadent ancient Rome,” Bilchester pointed to the Darling Bill as a typical example of legislation which is “saddling unborn generations with present debt.” “The project as outlined in this bill,” warned the prominent conservative, “is not only unnecessary; it is impossible of achievement, unsound in conception, obscure in meaning. Construction at this point is totally unwarranted by the needs of the surrounding community. After the first orgy of Federal spending, it will actually impose a handicap upon all legitimate business men of the district.”

… Well, Bill, here I am back again. Mr. Bilchester has been blowing off to the press about the Sparling Bill, which, I think, calls for a dam somewhere. Gosh, I wish you could help put the darned thing up! Anyhow, honey, don’t worry. The minute you get a job, I’ll be back. I’m not going out with any fellows here, and I don’t even want to, so what you said is all wrong. Lots of them ask me—cute looking ones, too—but I’d rather go to my room and dream about a house of our own, with you and me in it. I hope it’ll be in Chillburg, because Mom and Pop are getting old, and, besides, they would be handy to take care of the children. But I guess an engineer lives most anywhere there’s work. Anyway, I want you to quit worrying and talking about yourself being a hound, because it will give you a complex or something.

Your lovingest,

DORA.

—

WASHINGTON SKELETON

By A. E. McBride

Representative George W. Bilchester, one of the few to escape last fall’s steam roller, roared into page 1 of the conservative press yesterday with a denunciation of the Darling Bill. Unpleasant repercussions on Capitol Hill may result. Administration spokesmen are inclined to pooh-pooh the veteran congressman as a black reactionary, but Bilchester has a fanatical following in his fork of the creek, and his thunderings are not to be taken lightly. Moreover, he has selected a vulnerable spot for his attack. If the considerable study I have given the Darling Bill is worth anything, it is just the measure to crystallize opposition opinion in the House. Majority whips, unawed by meager opposition, fear most the possible insurgents within the party. They are clubbing down opposition to avoid any semblance of a party schism. Upon this fact I base a prediction that we will hear much more about the Darling Bill.

OFFICE OF REPRESENTATIVE GEORGE W. BILCHESTER

DARLING BILL: Oh, gosh, honey, what a mess I’m in! You keep writing me and accusing me of not loving you and of going out with other fellows until I just want to cry. I’ve been crying pretty steady now for almost all night. And it’s all because I love you, Bill, with all my heart and soul. I should think you’d believe in me, darling; and after you hear what has happened to me, I guess you won’t need any more proof. I’ve got to tell somebody, and when I’m tired and homesick, I always think of my darling and of Mom and Pop in Chillburg. So now, at three in the morning, I’m writing, and maybe you’ll see the tear spots on this very paper.

He kept waving a paperweight in front of me, and I thought he was going to kill me. He said he would smash my head, except that he was no Moses and couldn’t strike water out of a rock. (Illustration by D’Alton Valentine, © SEPS)

He kept waving a paperweight in front of me, and I thought he was going to kill me. He said he would smash my head, except that he was no Moses and couldn’t strike water out of a rock. (Illustration by D’Alton Valentine, © SEPS)Do you remember the letter I wrote you that was interrupted by Mr. Bilchester coming in with an old press statement? Well, in that statement he got awfully mad at the Sparling Bill, which, as I explained in that letter, is going to be a dam somewhere which I sure wish you could help put up. But, honey dear, all the time I was taking his dictation for that statement, I was thinking of you and how you say that you’re a hound, and that I don’t love you and all, and I wrote it down in my notebook as “Darling Bill” instead of “Sparling Bill.” Because, sweetest, whatever you think or hear, you are always in my mind and in my heart. So this statement went to all the newspapers in the world with Mr. Bilchester talking about a Darling Bill which simply doesn’t exist anywhere—except you know where, honey.

Goodness! I never saw anything like Mr. Bilchester when he read that statement in the papers. He came running into my office and yelled at me that I’d ruined him after sixteen years of fearlessly fighting for the people of Chillburg. Fighting for Mom and Pop, he said, and for everybody, including the country and the Constitution; and then I had run a knife in his back, and brought the temple crashing down on his head like Delilah, and disgraced him before all civilization, and set him up in the stocks for history and the administration to hoot at. He said I had betrayed my country and made it possible for the depression to last forever—and a lot more, darling, that I can’t remember.

He kept waving a paperweight in front of me, and I thought he was going to kill me. He said he would smash my head, except that he was no Moses and couldn’t strike water out of a rock. He said he was only Job, and that I was his affliction, and that he was going to purge himself of uncleanliness, and that I was fired. Well, honey, I just broke down and bawled. With that paperweight waving and him yelling and hollering, I lost my head, and first thing I knew I was screaming for Gladys Satter, who is two offices down. I yelled, “Help, Gladys, help!” Then Mr. Bilchester put his hand over my mouth, and I thought maybe he was going to strangle me, and I bit him good and hard.

Just then the phone rang. I guess that sure was a lucky phone call for me, because he stopped with his hand raised in the air, and hollered for me to get out and never show my face in his office again.

I ran out of the office and straight home, and I’ve been here ever since, even though a boy did call me up and ask me to go down to the Mayflower Grill with him. I guess I had a nervous chill, because the landlady said I looked terrible, and asked me if I had any statuary charges against Mr. Bilchester, because if I did, her brother was very good at that kind of thing. Then she put me to bed. I’ve been crying ever since, until it got so I just couldn’t stand it. So now I am writing to you. And I guess I’ll be home pretty soon, honey, and everybody’ll know that I was fired.

I hope you still love me, Bill, because if you didn’t, I’d just die. I want you so bad, and I will be glad to get away from this crazy town. It is no place for a person with refinement, honey. I’ll send you a telegram to let you know when you should come down to the station to meet

Your lovingest,

DORA.

—

INTEROFFICE CORRESPONDENCE

Memo from: E. J. S.

To: SENATOR MAPES

MY DEAR MAPES: Bilchester ran wild again yesterday. The administration doesn’t want to horn in on this, because the Darling Bill is fairly unimportant. But you know we can’t give an inch, or some of these funny new party members may kick over the traces.

Will you get the press boys together this afternoon and give old Bilchester the works? Make it strong. Believe me, I’m going to work on that district of his from now on.

E. J. S.

—

WASHINGTON SKELETON

By A. E. McBride

In one of the most withering blasts of recent months, Senator Chester L. Mapes today named Representative George W. Bilchester as “archconservative public enemy Number One.” The senator’s attack, in which he accused Bilchester of being “brazenly in league with Wall Street piracy,” was a response to Bilchester’s choleric denunciation of the Darling Bill, now pending in the House.

Challenging Bilchester to “name one constructive piece of legislation fostered by his party in the last three years,” Mapes denounced the small but potent bloc in Congress which, he declares, “values a balanced budget above a balanced diet.” Mapes asserted that “so long as there is human misery, this administration will spend money to relieve it, and so long as there is a need for such constructive projects as that embodied in the Darling Bill, the Federal Government will open Treasury gates for their realization.”

Astute observers, among them your correspondent, take the senator’s statement as indicative of the administration attitude. Opposition leaders declare the Mapes statement to be a brazen threat of punishment in the form of patronage limitation for anyone who tosses a wrench in the smooth passage of the Darling Bill.

—

OFFICE OF REPRESENTATIVE GEORGE W. BILCHESTER

DARLING BILL: Well, sweetness, things are beginning to look better, and I may not be back in Chillburg as soon as I thought I would be. You know what you always say about people having to have self-confidence and fighting for the right whenever they are clear on what the right is? Well, I got to thinking about that. And finally I decided that it wasn’t right for Mr. Bilchester to fire me just because I misspelled a tiny little word. And then I figured, like you say, that you should fight for the right just as hard when it’s yourself you’re fighting for as when it’s somebody else.

So the next morning I went down to the office just as if I was still working there, only I had much more self-confidence than usual, because I knew I really wasn’t. I walked right up to Mr. Bilchester, who was looking like he hadn’t slept all night, and told him that I had thought the matter out. I said I had decided that if the mistake I had made was so important, I guessed I would just go down to the newspapers myself and tell them there wasn’t any Darling Bill, and save Mr. Bilchester all that embarrassment. I told him also that I would tell the newspapermen how mean he had been in firing me, and how he had tried to break my head with a paperweight and strangle me, and how I had had to scream for help.

When he heard that he almost jumped across the desk. He told me I shouldn’t take that attitude, and began to pat my back. He told me that, after all, I shouldn’t take things so seriously, and that, of course, I wasn’t fired, and that he wouldn’t think of me taking all the blame for that mistake; just to let it pass and say nothing. He said he hadn’t meant all he said about Moses and Job and firing me, and that maybe I’d get a nice little present from him later. So I went into my office and he cocked his feet on his desk and began reading the morning papers.

In just a minute he came running into my office and showed me a piece in the paper where Senator Mapes had said a lot of nasty things about Mr. Bilchester and a lot of nice things about this old Darling Bill. I got all shaky when I read it, and started to bawl again. But Mr. Bilchester patted me on the head and said something about “out of the mouths of babes.”

“Scoundrels, all of them!” he said. “And this proves it! They don’t even know their own bills! That fellow McBride doesn’t know either. They’ve fallen into my trap! Oh, I’ll bet they’d give a million dollars for just some little swamp named ‘ Darling.’ For years I’ve fought the rascals, and now I have them where I want them! We’ll scourge ’em, Dora! We’ll scourge the Philistines!”

He gave me a funny look, like a crazy man or something, and I almost started hollering for Gladys again, I was so scared. He said something about justice, and told me I was going to get a raise for sure, and not to mention to anyone about my mistake, because it might make it hard for me ever to get another job. So, please, honey, don’t mention it down at Dubroc’s store. Then he said: “I’m going to issue a statement to the press. And it’s going to be about the Darling Bill—get it? And if you dare make a mistake and say Sparling Bill, I’ll strangle you with my bare hands.” So I took his statement, and my, you never saw anything like the things he said about the Darling Bill. He even challenged Senator Mapes to a debate about it, and he dared anyone from the President down to come out and tell the people what the bill called for.

So, you see, darling, everything is all right, and it’s all because you told me about self-confidence and fighting for the right. I’ve got my job, and Mr. Bilehester seems happy again with something to make press statements about, and although I’m crying my heart out to see you again, still it’s just as well one of us has a job, especially if what Mr. Bilchester said about my mistake helping the depression along to get worse is true. If things do get worse on account of a little mistake in spelling, it may be a long while before there are dams enough to go around, since, I understand, there are lots of engineers out of work; although none are as smart as you or half as sweet.

I am not going out with any fellows, darling, although, as I told you, I don’t go without plenty of invitations. I wish you’d stop accusing me of things which I don’t do. Goodness, it’s bad enough around here getting accused of things you really do do. I would like to be at the Gem Theater with you tonight instead of lonesome in my room. Stella wrote me, and said she saw you there with Vergie Peck. I hope you had a good time. Good night for now, honey.

Your lovingest,

DORA.

—

THE NEW YORK CALL HOME OFFICE

Memo from: CITY DESK

To: A. E. MCBRIDE

ANDY: Notice a lot of stink about the Darling Bill lately. Give us fifteen hundred words to catch the Sunday-feature sheet. Bilchester may stir up quite a mess out of this, and I think we should be protected. Your column notices on it weren’t very specific.

WALTER HARRIS.

—

THE NEW YORK CALL

WASHINGTON BUREAU

SENATOR CHESTER L. MAPES,

SENATE OFFICE BUILDING,

WASHINGTON, D. C.

MY DEAR SENATOR: The Call plans to run a detailed analysis of the Darling Bill Sunday. I remember it only vaguely as a hang-over from the last session. I ran something on it then, but I want to avoid a rehash. Perhaps you will dictate to your secretary those points involved which you consider most important.

Yours respectfully,

A. E. MCBRIDE.

—

INTEROFFICE CORRESPONDENCE

Memo from: SENATOR MAPES

To: E. J. S.

DEAR ED: What the hell is this Darling Bill about? I thought I remembered it vaguely as a hang-over from last session. Bilchester is heaping coals on me in the newspapers. McBride wants a story on it. On your suggestion, I saw Jim Lacey. He tells me there is no Darling Bill, has never been any Darling Bill. Now, if there isn’t any Darling Bill, we’d better find one damn quick. Bilchester will crucify the whole administration. You were the one who wanted me to lower the boom on Bilchester re Darling Bill, so what are you going to do about it? I’m not going to be the goat this time.

Yours,

CHET MAPES.

—

INTEROFFICE CORRESPONDENCE

Memo from: E. J. S.

To: SENATOR MAPES

CHET: Did you, or did you not, make a statement to the press praising the Darling Bill? If not, you have a swell libel suit against four press agencies and every first-rate daily in the country. If you did make such a statement, what were you talking about? Looks like you’ve got us in another jam. Agree we must find a Darling Bill. Suggest we meet tonight, 7:30, Mayflower. This is no time to be talking about goats.

E. J. S.

—

OFFICE OF SENATOR CHESTER L. MAPES

MR. A. E. MCBRIDE,

WASHINGTON BUREAU,

NEW YORK CALL.

MY DEAR McBRIDE: I hope you will pardon a little delay in regard to the Darling Bill. To tell you the truth, I have been ill since this matter came up, and am not at all well yet. Rotten weather here, for one from my part of the country. However, I am now going into the bill carefully, with a view to giving you a complete history of the thing. It is entirely too important to be slighted in any way. I suggest you postpone your story a week, in the meanwhile dining with me Monday at the Mayflower, at which time we can have a pleasant chat and also clear up any questions in your mind. Accept again my regrets for the delay.

Sincerely,

CHESTER L. MAPES.

—

THE NEW YORK CALL

WASHINGTON BUREAU

REP. GEORGE W. BILCHESTER,

HOUSE OFFICE BUILDING,

WASHINGTON, D. C.

MY DEAR CONGRESSMAN BILCHESTER: The Call is very anxious to run an analysis of the Darling Bill for the Sunday-feature section, and, of course, no summary would be complete without your opinion. While I know you oppose the bill, I am extremely desirous of having something specific from you upon it. What do you think of the type of structure it calls for? Is, in your opinion, the appropriation for it too heavy? What do you think of the circumstances surrounding its introduction to the lower House? I confess I’m a bit hazy on its history, and I know you can give me the most accurate résumé available. I’ll call at your office tomorrow for a good talk.

Sincerely,

MR. A. E. MCBRIDE.

—

OFFICE OF REPRESENTATIVE GEORGE W. BILCHESTER

MR. A. E. MCBRIDE,

WASHINGTON BUREAU,

THE NEW YORK CALL.

DEAR McBRIDE: I am leaving tonight for New York, hence am sending you herewith the material you request in connection with the Darling Bill. It would be sheer presumption for me to go into detail concerning this grave piece of legislation when addressing the shrewdest correspondent The Call has ever turned loose on us poor legislators. I won’t, therefore, insult your intelligence with petty details, for I suspect you press boys really know as much about the Darling Bill as we do. However, you may quote me as follows: