Editor’s note: “Five C’s for Fever the Five” was originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on November 30, 1935.

The boys in Mufti Joe’s place had just returned from a fortunate crap game in the Shore hotel down the street. Now they were sitting around the pool hall in various attitudes of relaxation. Fever the Five, however, remained a little apart from them, listening alertly to their conversation. Louis Parconi had a newspaper, and it was, therefore, upon Louis Parconi that Fever the Five bestowed his closest attention.

Although Fever the Five had an enormous interest in contemporary events, particularly those occurring in South Chicago, he numbered among his superstitions a positive conviction that it was bad luck to gain firsthand knowledge of anything from a newspaper. Just how this idiosyncrasy had crept upon him Fever neither knew nor cared; it existed, and hence was worthy of respect. Whenever the latest editions were at hand, Fever the Five invariably could be found lurking in the background, where he might assimilate verbal comments on the news of the day before perusing the sheet for himself.

“I see,” Louis Parconi was saying, “where they fry this Nick Kosteff in the morning. The governor just turned thumbs down on a reprieve.”

The observation elicited a round of sympathetic tongue cluckings. The habitues of Mufti Joe’s place themselves lived so perilously on the hairline of crime that they were bound to take a melancholy interest in one who had slipped irrevocably to the other side.

“No!” breathed Ziggety Dockstadter. And then, morbidly: “Read us about it, Louis.”

Fever the Five leaned against a pool table and listened intently.

“As the sun faded upon his last day of life,” read Louis Parconi, “Nick Kosteff, protection racketeer and convicted murderer of two Chicago fruit merchants, tonight received word from the chief executive’s office that his appeal for a reprieve has been rejected. Kosteff, who inherited the organization of the so-called Sicilian Syndicate, was convicted in August, after two previous trials had resulted in hung juries. With the governor’s denial of reprieve, his long fight for life comes to an end. He will march from the death cell to the electric chair at eight o’clock tomorrow morning.”

Louis Parconi lapsed into a silence which endured for almost a minute before it was broken by Ziggety Dockstadter, who had followed the case from its inception with avid interest. “It shows,” pointed out Ziggety Dockstadter, “that shooting fruit peddlers is the wrong way to beat a depression.”

“And such a young guy too,” mourned Willie Jeems sentimentally. “Oh, well, in one ear and gone tomorrow.”

“Yeah.” Louis Parconi grunted, and gave a little shudder. “Tomorrow he’ll be so hot he’ll melt and run down his own leg.”

At this point, Fever the Five decided he might risk looking at the newspaper himself. He sauntered to a position directly behind Louis Parconi and glanced obliquely at the item. There it was, just as Louis Parconi had pointed out:

GOVERNOR DENIES KOSTEFF REPRIEVE

KILLER OF TWO DOOMED TO CHAIR

Having verified the item with his own extraordinarily skeptical eyes, Fever the Five went into a one-man huddle. To his mind, the case presented interesting possibilities, and interesting possibilities played a large part in Fever’s financial well-being.

Fever the Five, fundamentally, was a very slick guy. He could spot a doped bobtail at fifty paces, a phony game of twenty-one at fifty feet, and a loaded set of dice in fifty seconds. And why shouldn’t he? He came from that section of Loo’siana where they nourish their young on whisky and ‘lasses, teach the ABC’s from a racing chart, and abandon all hope for a ten-year-old who can’t run the family roulette wheel to a heavy house percentage.

At seventeen, in his father’s Mississippi waterfront saloon, Fever the Five had handled three telephones simultaneously, quoting odds from his own fertile mind on every up-and-up track in the country. Now, at twenty-eight, his eyes were smart, and his ways were smart, and his clothes were even smarter than anything else about him.

In addition to his better-known virtues, Fever the Five—the name intoned by the priest at his christening had been John Baptist Edwin Michael Joseph LeFevre—had the rare gift of analyzing his talents, estimating his limitations, and keeping rigidly to the safe side of both. In his own circle, bounded by the four walls of Mufti Joe’s Chicago billiard parlor, he was nonpareil. He went around with his head full of long-shot figures, and he made his bucks as he needed them.

He had never been in serious difficulties with the law, either. Oh, a hot crap game here, perhaps, and a raided bookie joint there, but nothing that fifty fish wouldn’t sweeten. Of late, however, he had been afflicted with police trouble of a most irritating nature. It was his misfortune closely to resemble one Waddles Bellefonte, newly risen larcener who was achieving spectacular publicity for his ability to steal other people’s property—chiefly negotiable jewels— and the state’s inability to convict him. More conscientious citizens than you might think, seeing Fever the Five here and there in brightly lighted spots, had been impelled by this coincidence to sum- mon the gendarmerie, with results which were never serious, but which were bound to be intensely annoying to a man of Fever the Five’s vanity.

By now, of course, most of the police were aware of his unhappy likeness to Waddles Bellefonte, and didn’t bother him more than once or twice a week. But there had been a period when Fever the Five had scarcely dared thrust his nose beyond Mufti Joe’s doorway. Time had enabled him to accept the circumstance with philosophical resignation. His disposition was not soured by it, and the only permanent effect upon his character was, naturally enough, a deep resentment toward conscientious citizens.

But now, listening to conversation about a murderer he had never seen and for whom he could gen- erate only professional interest, Fever the Five felt that the injustice of his resemblance to Waddles Bellefonte was about to be turned into profit. Having pondered over the miserable fate of Nick Kosteff for an appropriate period, he delivered himself of a remark which was destined to a high place in the annals of Mufti Joe’s billiard parlor.

“You’re never sure a guy’s dead until he’s dead,” observed Fever the Five. “Anything might happen.”

Louis Parconi wheeled slowly in his chair and stared up at the speaker. Experience had taught him that Fever the Five’s remarks were never ill considered, yet in the present instance he felt that the condemned man’s fate was a matter beyond academic or even philosophical discussion.

“Nuts,” he stated simply. “One appeal’s been thumbed. The guy’s got no dough to go higher. The governor says to turn on the juice. That’s enough for me. As far’s I’m concerned, the guy is six feet deep right now.”

“I hear the exits to that death house are very, very strong,” pointed out Willie Jeems.

“ Um-m-m,” murmured Fever the Five enigmatically. “Just the same, I wouldn’t give too big odds on it if I was you.”

“ Odds !” exclaimed Louis Parconi. “I’d give 20 to 1 any time.”

“Would you give 10 to 1 right now?” gently inquired Fever the Five.

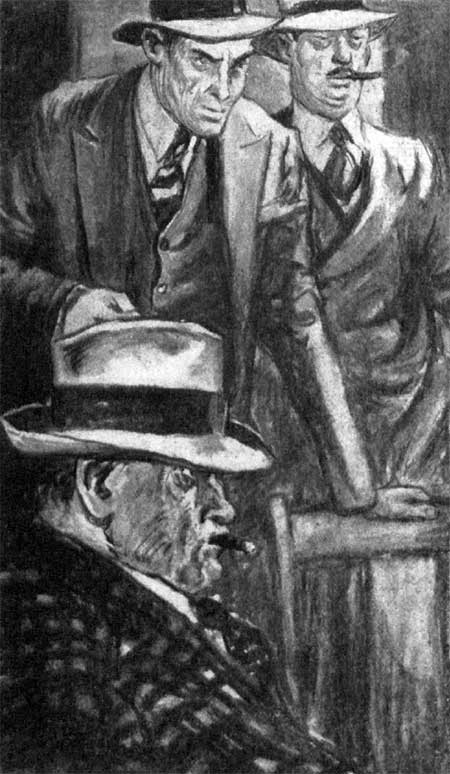

Silence crashed over Mufti Joe’s place like a pineapple in a dry-cleaning joint. The faces of Louis Parconi and Ziggety Dockstadter and Willie Jeems and Ace Cardigan and even of Mufti Joe himself fell into blank defensive masks. Like sheep startled by an interloper, they stared at Fever the Five. They stared placidly, stolidly, and waited for him to repeat his incredible proposition.

“I said would you give 10 to 1 right now?” insisted Fever the Five’s suave monotone.

“ You want 10 to 1 this guy don’t fry,” stated Louis Parconi contemplatively.

“No. I want 10 to 1 he’s alive tomorrow night.”

A nervous shifting of positions seized the boys in Mufti Joe’s. Louis Parconi glanced sleepily from face to face. Not a feature changed, not an eyelid twitched, yet by the time he had completed his inventory Louis Parconi knew precisely how each man felt about the proposition.

“How much?” he inquired languidly.

“I’ve got fifty that’s waiting for five C’s to cover it,” declared Fever the Five.

“Personally,” averred Louis Parconi, with elaborate disinterest, “I don’t care to lay out so many bucks in one stack. But I might scrape up a C if the rest of the boys would like to climb on.”

Again a faint restlessness passed through them. Dockstadter’s voice froze them to immobility.

“Maybe you’ve got inside dope on this party,” said Ziggety Dockstadter irritably. “Before I send a C out after a ten-spot, I call up the newspaper and find out if this yarn is not a phony.”

“Call now,” urged Fever the Five.

With the eager haste which had won him his mon- iker, Ziggety Dockstadter scuttled up front to the telephone booth. During his absence Louis Parconi calmly turned the pages of his newspaper. Fever the Five retired once more to a discreet distance, while the others resumed the stances which had been disturbed by his aberration. Then Ziggety Dockstadter returned.

“It’s straight,” he announced. “The guy says the only thing can save him from cooking is a short circuit.”

Although no one said anything, the very air of Mufti Joe’s place crackled with thought. They all had sufficient money to cover the bet, because it was their business to have money. But the wisdom of risking so much for so little was another matter. On one hand, they had the facts of the case—apparently legitimate—and the facts were entirely in their favor. On the other side of the coin, they had Fever the Five, who was notoriously reluctant to play fast and loose with his wampum. Either Fever the Five was operating on a hunch or upon inside information. • Since they knew his friends and enemies, his women and his party spots, they were comfortably certain that he had no informant who could learn of a reprieve in advance. Hence, weighing all visible factors in the equation, they were forced to conclude that Fever the Five was backing a crazy premonition.

“It’s worth a whirl, Fever,” said Louis Parconi, smashing the silence to fragments. He tossed two fifties onto the green baize of the pool table. “Mufti Joe here all right to hold stakes?”

“Sure,” agreed Fever the Five. “Only, since five is my lucky number, I don’t plan to bet unless I get coverage for the whole fifty.”

Ziggety Dockstadter, hypnotized by the sight of Louis Parconi’s money on the table, shook off his hesitance, broke out a hundred dollars and reverently laid it beside the two fifties. He wet his lips, but no words issued from them.

“I always say there is no worse bet than the long end of crazy odds,” commented Ace Cardigan. “But on the other hand, I don’t believe in miracles either.”

He placed the third hundred on the table.

Willie Jeems said, “Gosh! I didn’t come out near as good up at the Shore as the rest of you guys. But I got fifty here that is very hungry for another fin.”

“I’ll take the odd fifty,” murmured Louis Parconi.

“That leaves a hundred open,” pointed out Fever the Five suggestively.

For an instant they gazed blankly at one another, as if each expected his neighbor to break the impasse. Then Mufti Joe spoke.

“If you don’t mind about the stakeholder coming in, I’ll take that last piece,” he announced softly.

“Shoot,” said Fever the Five.

Mufti Joe peeled one bill from his roll. Five hundred and fifty dollars lay temptingly on the baize.

“Tuck it in your safe, Joe,” directed Fever the Five.

Mufti Joe went up front and stuffed the money into a little safe behind his cash register.

“Watch it,” he said to Frankie Fink, his assistant.

Each man resumed the position which had been his when the fate of Nick Kosteff first became a topic of conversation. Ziggety Dockstadter and Willie Jeems started chalking their cues. Ace Cardigan, his hat well down over his eyes, sank into his high observer’s chair and seemed gently to fall asleep. Louis Parconi buried his head once more in the newspaper. Mufti Joe began to set down figures in a little book which he always carried. But each of them, sidewise out of slanted eyes, watched Fever the Five as he moved jauntily toward the front door.

“So long,” said Fever the Five, giving a little more tilt to the brim of his pearl gray. “ So long, and good-by all.”

—

Fever the Five walked briskly through a sea of varicolored lights toward his hotel two blocks southward. He paused only once, and that time before Hennfinger’s Cut Rate Nut Shop. In the window of the Hennfinger emporium sat a jar of peanuts, beside which a placard proclaimed that ten dollars would be awarded to the lucky customer who came nearest to estimating the correct number of nuts in the jar. Such a proposition was calculated to appeal to the sporting instincts of any South Side gentleman, and Fever the Five was no exception. He read the placard twice and squinted appraisingly at the jar.

Such was the depth of Fever’s cynicism that he confidently believed Papa Hennfinger for a half of the ten-dollar prize would be not at all loath to reveal to him the correct number of peanuts, thereby netting an easy fin both for Fever and Papa. Although it was not what one might call a big deal, Fever had learned in a hard school that twenty fins make a C, and that a C is worthy of any man’s devotion. But of course the current business was too important to delay. Perhaps tomorrow—

“Figurin’ where your cut comes in?” inquired a pleasant voice behind him.

Fever the Five whirled to see who had interpreted his thoughts so correctly. It was Mike Geraghty, a member of the constabulary who upon several occasions had mistaken Fever for Waddles Bellefonte, with much accompanying confusion.

“Flattie,” responded Fever affably, “that’s one reason you’re pounding a beat—while you think of ten bucks, I’m geared to five C’s.” Fever tapped his own immaculate chest to emphasize his point. “I’ll be wearing diamonds as big as those nuts when you’re still shining brass buttons.”

”Sure,” said Mike Geraghty soothingly, “sure you will, Fever.”

Fever the Five felt that the conversation was getting nowhere. Moreover, he had affairs afoot.

“I’ll be going,” he told the grinning policeman. “Every minute I’m standing here talking to you, I’m throwing coin to the ducks and geese.” He moved away from Hennfinger’s window, pausing only long enough to deliver himself of a final insult: “Those bunions’ll freeze on you one of these days unless you give ’em more exercise.”

Without a backward glance, he continued his journey hotelward.

In his room with bath he rummaged through a bureau drawer, from which he presently withdrew a sheet of hotel stationery. With great care he tore the heading from the page. Then he extracted a gold pencil from his vest pocket—at least the man in the hock shop had sworn by Abraham that it was gold, although Fever the Five was prone to discount such protestations. He sat down by the nightstand and began to write. When he had finished, he read his handiwork twice, grunted pleasantly, and folded it into his inner coat pocket.

Although it was a hot summer’s night, he lifted a natty blue double-breasted overcoat from its rack in the closet and swung it over his arm. He inspected his reflection in the mirror, twitching his eyebrows in a manner which he considered fascinating to women.

At the door he paused, taking quick mental inventory. Then, well satisfied, he swung from the room.

On the street again, he hailed a taxi, drove six blocks and debouched. In a corner drugstore he carefully closed the telephone-booth door behind him, consulted the directory and dialed The Call. He was familiar enough with newspaper argot to ask for the city desk. When the Cerberus in charge issued his tersely professional challenge, Fever the Five spoke softly and swiftly:

“Listen to what I say, and listen close, because it’s the last time you’ll ever hear it. There won’t be time to trace this call, and I’m not answering any stall questions you throw to me. If you send somebody around to the Painter Street telegraph office in the next ten minutes, they’ll find something very interesting which might make a swell story for the midnight edition. That’s all, toots. So long, and good-by all.”

He killed a protesting yelp from the other end of the wire by the simple expedient of snapping the receiver to its hook. Then he walked from the drugstore and entered a second taxi. This one he permitted to transport him within two blocks of the Painter Street telegraph office. There he dismounted and paid the driver.

He strolled nonchalantly through the crowds until, in the middle of the block; he spotted the conveyance for which he was searching—a limousine flaunting a “For Hire” sign. Lolling in its front seat, the driver smoked a cigarette and meditated upon the dark traceries of a chauffeur’s fate.

“Hey, toots,” said Fever the Five. “How’d you like to make fare and a ten-spot?”

The driver regarded Fever the Five thoughtfully, but he did not permit the suggestion to take him by storm.

“If there’s any shooting, it costs fifty bucks,” he declared in a flat voice.

“No shooting,” protested Fever the Five. “ It’s very simple.”

“It’s gotta be simple for a ten-spot,” averred the driver. “What’s the angle?”

“Cover your license plates and drive me four blocks. If the cops get you on the plates, I pay the fine. When we hit the corner just beyond the telegraph office, you pull to the curb. I step out and talk to a newsboy for a minute. I step back again. You drive me two blocks farther to the taxi stand. There I leave you. You circle the territory and come back here with plates uncovered. That’s all. How’s it sound?”

“It sounds good,” said the driver, after the fashion of a man accustomed to making prompt decisions.

He climbed out of his seat and produced two rags from a side pocket. These he affixed to his license plates fore and aft. No one noticed, because no one ever notices. The driver’s knowledge of this fact enabled him to perform the illegal task with magnificent aplomb.

“Climb in, brother,” he invited as he dusted his hands against trousers.

“Pay you first,” said Fever the Five softly, pressing fifteen dollars into the suddenly outstretched palm. “Understand,” he cautioned, “this is strictly confidential.”

The driver closed one eye, nodded waggishly and opened the eye again.

They were off.

As they passed the telegraph office, Fever the Five noted with satisfaction that three men were loafing beside the counter, and that none of them was sending a telegram. The Call had not failed him. He leaned forward and wriggled into the blue double-breasted overcoat. At the corner, the limousine slid gently to a stop. Fever the Five stepped out and hailed a newsie. The collar of his coat was hoisted, the brim of his pearl gray drooped, and all that remained visible of his face was a nose and a mouth.

“Hey, bud,” greeted Fever the Five.

The newsie ran to him, paper extended.

“No, not that!” With a little grimace of horror, Fever the Five waved the paper aside. “Want to make a fin?”

“Yar!” said the youngster, his eyes gleaming with anticipation.

“All right. Here’s a pencil and paper. Now copy what you read off this piece of paper onto the clean one.”

Fever produced the note he had written in his hotel room. The newsboy had seen too many strange things in his young life to ask questions. With the utmost care he copied Fever’s words onto the blank piece of paper.

“Now give me that.”

The boy handed back the original note.

“What you have there is a message,” explained Fever precisely. “Take it into the telegraph office. Don’t pay them for it, because you can see it’s marked ‘collect.’ Hand it to the man in charge and run like hell. You don’t have any idea what I look like, or that I’m wearing an overcoat, or that my plates are covered. Understand? Because I’m taking it on the lam. Compre?”

“Sure, I compre.”

“Right. Here’s the five. Now remember what I told you, baby—and don’t get mixed up!”

“Okay, mister! And thanks very much for the —”

The response faded rapidly, because Fever the Five was already back in the limousine, moving sedately toward the taxi stand two blocks distant. There he climbed from his equipage for the second time. His overcoat was hanging across his arm. He stood on the curb and made a flat-palmed, circling gesture of farewell.

The driver grinned, clashed his gears and departed. Around the corner he pulled to a stop and removed the rags from his license plates. Then he continued happily back to his stand for a resumption of interrupted meditations.

Fever the Five, leaning back against the cushions of his cab, considered the two hours which lay immediately before him. He resolved upon a movie as the most agreeable time-killer. Before one which heralded Wild for Women in flaming red letters, Fever the Five ordered a halt.

“One ticket, beauty—and the change is for you,” he chortled to a ticket girl whose hair was as red as the house sign.

“Sixty cents, mister,” chanted the girl through her nose. “Another dime, please—and keep the change!”

Fever the Five produced another coin and grinned. He glanced at his wristwatch. It was two minutes until nine.

—

At 11:30 the city blossomed with dingy white flowers that were tomorrow morning’s newspapers. Fever the Five, coming out of the theater, avoided them fastidiously. It required all his will power, however, to refrain, from stealing a quick glance at the headlines. He strained his ears to the cries of newsboys, but they were shouting trivialities about Congress and the Supreme Court, in neither of which Fever the Five had ever been able to sustain the slightest interest. He passed rapidly down the street, wondering how he was going to obtain the information he needed without reading it.

Then sheer inspiration descended upon him. He turned in his tracks and headed for Abe Bernstein’s Kosher Restaurant. There was a good chance one of his friends would be dropping by for a bite to eat, and if not, the place was always infested with old men who solemnly dissected the newspapers item by item, making each story the subject of acrimonious debate. When he reached Abe Bernstein’s, he took a seat at the counter, ordered a cup of Java and watched the door alertly.

The sight of Sammy Schiff shuffling through the entrance was a thing to cheer Fever the Five’s heart. Sammy Schiff had a small piece of a minor slot-machine racket, and was usually a very pleasant guy. Besides, he carried a morning newspaper.

”Hi, toots!” greeted Fever the Five. “Howsa boy? I been waiting for you to come in, so’s I could buy you a pastrami sandwich!”

Sammy Schiff regarded Fever the Five with mild surprise.

“Sure,” he said in a puzzled voice. And then to the waiter: “My friend wants I should have a pastrami sandwich.”

He spread his newspaper flat on the counter and, starting with the upper left-hand corner, began methodically to go over the front page. Fever the Five rolled his eyes upward, downward, toward the door, backward to the tables, but never toward Sammy Schiff’s newspaper.

“I see,” ruminated Sammy Schiff, “where it says that another old bat has plugged her meal ticket and a young skirt. It goes to show that no dame should ever be let have a gat.”

“Yeah,” said Fever the Five. “That’s the hot spot for her. They burning anybody in Joliet today?”

“They’re always burning somebody in Joliet.”

Fever the Five sighed and took a sip of his coffee.

“A rich guy across town has been slugged for a diamond ring, and also I see where they’re talking about they should strike again,” said Sammy Schiff implacably. “What I can’t understand is how us working guys are ever going to get along if there is always someone agitating us to stop working. It don’t make sense.”

“No,” said Fever the Five firmly. “And strikes always end up in shootings, and shootings cause guys to be cooked. Personally, I wonder if anybody is getting ready to be cooked in state prison today.”

“Somebody is always getting ready to be cooked in state prison,” declared Sammy Schiff. “It says here that gents’ clothing is going to be brighter, with a big revolution against dull tints and all that quiet stuff.”

Fever the Five clutched his coffee cup, but made no comment.

“Now, here,” said Sammy Schiff, “is a funny thing.”

“Yeah?” said Fever the Five eagerly through his nose.

“Yeah. It seems that Nick Kosteff is scheduled to be fried this morning. Only now the governor has slipped him seven more days.”

“Oh, no,” tantalized Fever the Five. “You must be reading that wrong.”

“How do you mean—reading it wrong?” demanded Sammy Schiff hotly. “Here, read it yourself!”

Fever the Five almost fainted as Sammy Schiff thrust the newspaper under his nose.

“No!” he babbled despairingly. “It hurts my eyes to read in this light. You read it, Sammy.”

Sammy Schiff looked surprised, then shrugged his shoulders and addressed himself to the paper.

“Nick Kosteff,” he read, “the West Side protection racketeer, scheduled to die this morning for the murder, last May, of two fruit dealers, was snatched from doom at eleven o’clock last night by virtue of executive reprieve. Kosteff’s execution was delayed one week as the result of a telegraphic confession signed ‘Mr. X,’ filed yesterday at 8:56 P.M. with the Painter Street telegraph office. Mr. X is believed by authorities to be Waddles Bellefonte, police character and asserted jewel thief.

“The telegram purporting to confess the double crime was addressed to the governor, and presented at the Painter Street office by Tony De Cenza, a newsboy. De Cenza had received it a moment previously from Mr. X, who stepped from a high-powered limousine to send him on the errand. De Cenza copied the message from one handed him by Mr. X, thus precluding any chance of identifying the sender by handwriting. The car’s license plates, according to De Cenza, were covered. Police obtained a detailed description of Mr. X from the newsboy, after which he was conducted through Rogues’ Gallery. It was there that the youth positively identified Mr. X as Waddles Bellefonte. Two passersby who witnessed the transaction between Mr. X and the newsie have since verified the Bellefonte identification.

“Although authorities are inclined to discount the telegram as a hoax, the mysterious circumstances surrounding its presentation and the injection of the Bellefonte angle determined the governor to postpone Kosteff’s execution until a fuller check can be made.

“‘I cannot stand by and see an innocent man electrocuted,’ began the amazing message which —”

Fever the Five coughed discreetly.

“That’s enough, Sammy,” he interrupted, gulping his coffee and slapping a half dollar onto the counter. “Besides, I just remembered a date. About that newspaper story”—his voice sank to a confidential monotone—“I don’t think anything will ever come of it.”

Sammy Schiff stared up at Fever the Five in milkish bewilderment. Fever the Five clapped him lightly on his pudgy back as a token of farewell, and moved toward the door.

Fever hailed a taxi outside and went directly to his hotel, where he left his overcoat. Eight minutes later he arrived before Mufti Joe’s place. Through the window he saw Louis Parconi and Ace Cardigan and Willie Jeems and Ziggety Dockstadter and Mufti Joe standing by the cash register, reading an outspread newspaper. As he entered, they turned gray faces from its front page to Fever the Five. Automatically, but with the exaggerated deliberation of a slow-motion picture, Mufti Joe reached into his safe. When his hand returned to the counter, it pushed a roll of bills toward the newcomer.

“You win,” he intoned reverently. “The governor just signed a reprieve for Nick Kosteff.”

“Thanks, toots !” said Fever the Five. And then, in a lower tone: “I got 10 to 1 says he don’t sign another.”

—

Fever the Five was back in the street and heading for his hotel when he felt heavy hands upon his shoulders. He whirled to face Mike Geraghty and Slim Bowen, who often traveled with Mike on the night beat. Fever was shocked to see that their faces were grim; he was nearly paralyzed to discover that they also had a gun jammed against his stomach.

“Hey, soft arch,” objected Fever the Five, “you can’t do this to me! What’s the rap?”

“Robbery, me lad,” said Mike Geraghty. “You should of stuck to the ten-buck rackets.” Fever heaved a sigh of relief. A dozen lesser charges would have filled him with consternation, but the obvious absurdity of robbery seemed so amusing that he burst into hearty laughter.

“All right,” he gasped after the laughter had passed, “I’ll bite. Who’d I rob?”

“You ask the questions,” murmured Mike Geraghty approvingly as he snapped a pair of handcuffs over Fever’s wrists, “and we got the answers. Fellow the name of Rankin. Got clipped on the jaw tonight in his room at the Kipp-Harris Arms across town. He woke up missin’ an eight-carat sparkler.”

“Nuts!” stated Fever the Five.

“That’s right,” said Mike Geraghty; “it was you told me you’d have diamonds the size of nuts, wasn’t it? I been tryin’ all night to remember who that was.”

“Go on and let me hear some more,” said Fever the Five, “because I got an alibi that’ll knock your eye out.”

“Glad t’accommodate,” purred Mike Geraghty. “Couple of fellows saw a guy in a blue suit and a gray hat scram out the back door of the Kipp-Harris Arms just about the time Rankin caught it on the button. We took ‘em down to the gallery, and they kinda figure that your mug matches pretty well with the guy they saw.”

Fever glanced sharply at the detective. He felt that the joke was being carried a bit too far.

“What time was the job pulled?”

“Rankin says just about nine straight up.”

Fever the Five tittered nervously.

“You mugs got me mixed up with Waddles Bellefonte again!” he giggled. “The only thing dumber’n a Chicago copper comes with hair all over it!” Gazing at the skeptical faces of the two detectives, Fever was gripped with sudden panic. “Don’tcha understand? It was Waddles Bellefonte pulled that job, because at nine o’clock I was —”

“Forget it,” interrupted Mike Geraghty paternally. “We got three witnesses saw Waddles on a corner next to the Painter Street telegraph office at five minutes to nine. I don’t hardly guess he could have got clear across town in five minutes. Waddles was wearin’ an overcoat too. That double-exposure stuff’s been good for quite a while now, Fever. But I wouldn’t advise you to pull it right this minute, ‘cause the way things look, Waddles is stuck for a nice long sentence himself.”

Fever the Five’s forehead wrinkled with baffled concentration.

“Let me get this straight,” he demanded. “What’s Waddles gotta stretch comin’ up for?”

“Oh, maybe a murder, maybe a conspiracy to impede the execution of justice, or maybe just a false information charge. Any one’ll add up to plenty of years. Come on, boy; let’s go.”

“No!” protested Fever. “You guys got nothing on me. Search me. Go ahead!”

“Okay, mister.”

They went through his pockets with swift efficiency. Mike Geraghty whistled to himself as he drew a sheaf of bank notes from Fever’s wallet and began counting them.

“Five hundred and sixty-seven fish,” he announced reprovingly. “Not so good for an eight-carat rock, Fever. But then, I ‘member you told me you was geared to five C’s.”

As they began hustling him toward the curb, Fever the Five’s heart ached with a great sickness for Loo’siana, where a guy wasn’t always being framed. Mike Geraghty’s voice came dimly to his ears.

“When you graduate from Joliet,” Mike was saying, “the first thing I’d do would be to take a healthy poke at the fence who give me five C’s for a sparkler worth ten grand. ’Twasn’t fair, Fever. He’d never of got away with a deal like that on Waddles Bellefonte.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now