In the summer of 1957, Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss, had just published a children’s primer called The Cat in the Hat, and his newest story, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, was ready for publication later that year. It was during this interlude that Geisel granted his first Post interview with Robert Cahn, revealing why he became Dr. Seuss, the simple reason he draws the way he does, and the undeniable effect his wife, Helen, has had on his career.

The Wonderful World of Dr. Seuss

By Robert CahnJuly 6, 1957 — Theodor Geisel, alias Dr. Seuss, has captured the imagination of millions of children with his fanciful spoofs: Gerald McBoing-Boing, the Drum-Tummied Snumm, and other creatures from a world of happy nonsense.

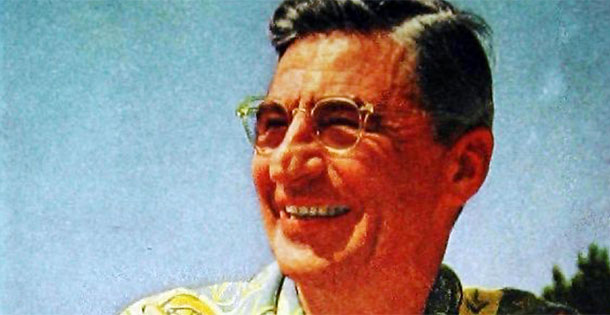

For a man whose mind is inhabited by such creatures as a Mop-Noodled Finch, a Salamagoox, or a Bustard — “who only eats custard with sauce made of mustard” — Theodor S. Geisel looks disarmingly rational. As the renowned Dr. Seuss (rhymes with “goose”), he is not, as a few children have pictured him, a wizened old man with flowing white beard. He is whiskerless, has the standard number of arms and legs, and lives quietly with his wife and dog on a hill overlooking La Jolla, California.

Yet for the past thirty years, under the protective alias of Dr. Seuss, Ted Geisel has been an apostle of joyous nonsense. He has fathered a whole modern mythology of bizarre creatures like the Remarkable Foon, “who eats sizzling hot pebbles that fall off the moon,” or the Drum-Tummied Snumm, “who can drum any tune that you might care to hum—doesn’t hurt him a bit ’cause his drum-tummy’s numb.” He has created young Gerald McBoing-Boing, the little boy who cannot speak, but makes sound effects instead. And he is still remembered for the impertinent bugs he concocted along with his famous advertising slogan: Quick, Henry, the Flit!

His annual output of picture books, like Horton Hatches the Egg, Thidwick the Big- Hearted Moose, and On Beyond Zebra, have become a part of the basic children’s literature of the country. They are in constant use at the overseas libraries of the United States Information Agency and have been translated into several foreign languages, including Japanese.

In suburban La Jolla, however, Geisel’s madcap alter ego is completely obscured. Here Theodor Seuss Geisel — Seuss is his mother’s family name — is considered a paragon of propriety. He is a director of the town council, and a trustee of the neighboring San Diego Fine Arts Gallery. His hair is cut regularly, his shoes are always shined, and he gives up his chair when ladies are standing.

The first impression of conservatism is emphasized by his polite attentiveness, not unlike that of a middle-aged bank vice president. Slim and tall, he has graying dark hair parted more or less in the middle. He is as sharp-eyed as a bird, with a long aquiline nose and a wide mouth which has a habit of twisting into puckish grins. And he speaks in the terse hesitancies of the painfully shy man.

But beneath this outer austerity beats a wildly impulsive heart. Even with the most serious intentions, the mind of Ted Geisel is so fanciful that he has never been able completely to subdue it. And he depends at all times on the levelheadedness of his wife, Helen, to pull him out of entanglements in which he has become errantly involved. Yet the unorthodox appearance of the Seuss animals is not entirely due to Geisel’s imagination. The fact is, as Geisel admits, “I just never learned to draw.”

“Ted never studied art or anatomy,” explains Helen. “He puts in joints where he thinks they should be. Elbows and knees have always especially bothered him. Horton is the very best elephant he can draw, but if he stopped to figure out how the knees went, he couldn’t draw him.”

Although the greatest audience for his animals is children, the nonsensical creatures are also in great demand among advertisers seeking a humorous presentation for their products. Sometimes, however, his business clients have lacked the willing imagination of his younger devotees. Once he had to do a horned goat for a billboard. The job was done and paid for, and everyone seemed happy, when the phone rang.

“Now, Geisel, about that goat,” said the advertising-agency executive. “We like it here and it’s a fine goat, but there is just one little thing wrong. Our client thinks it looks like a duck. So would you mind doing us another one?”

To resolve the problem, Geisel drew a duck and submitted it. The client called him up. “Geisel,” he said, “it’s perfect. Best goat I ever saw.”

Children, of course, understand and accept Geisel’s pictures, a fact which led to an unusual assignment two years ago during the height of the controversy over why Johnny can’t read. Textbook publishers and some educators and parents had realized that one trouble was that Johnny’s reader wasn’t readable. Most creators of children’s primers, though experts in form, failed miserably as storytellers. What was required, the publishers knew, was the kind of story that would lead a child from page to page with suspense and delight. Yet most writers were unwilling to accept the severe vocabulary limitations required for a first-grade reader.

Into the impasse stepped Geisel. He offered his services to one of the nation’s leading textbook publishers and was assigned to prepare a book that six-year-olds could read themselves. Unfortunately, the situation soon got out of hand.

“All I needed, I figured, was to find a whale of an exciting subject which would make the average six-year-old want to read like crazy,” says Geisel. “None of the old dull stuff: Dick has a ball. Dick likes the ball. The ball is red, red, red, red.”

His first offer to the publisher was to do a book about scaling the peaks of Everest at sixty degrees below zero.

“Truly exciting,” the publisher agreed. “However, you can’t use the word scaling, you can’t use the word peaks, you can’t use Everest, you can’t use sixty, and you can’t use degrees.

Geisel shortly found himself with a list of 348 words, most of them one-syllable words, which the average six-year-old could recognize — and not a Yuzz-A-Ma-Tuzz or Salamagoox among them. To one who was used to making up new words at will, it was a catastrophe. And yet the publisher had said, “Create a rollicking carefree story packed with action and tingling with suspense.”

Six months after accepting the assignment, Geisel was still staring at the word list, trying to find some words besides ball and tall that rhymed. The list had a daddy, but it didn’t have a caddy. It had a thank, but it had no blank, frank, or stank. Page after page of scrawls was piled in his den. He had accumulated stories which moved along in fine style but got nowhere. One story about a King Cat and a Queen Cat was half finished before he realized that the word queen was not on the list.

One night, when he was almost ready to give up, there emerged from a jumble of sketches a raffish cat wearing a battered stovepipe hat. Geisel checked his list—both hat and cat were on it. Gradually he worked himself out of one literary dead end after another until he had completed his children’s reader.

The Cat in the Hat was published last spring by Houghton Mifflin as a supplementary school text for first graders, and in a popular edition by Random House. It already has been greeted enthusiastically by parents and educators. The story line concerns fanciful adventures occurring when a vagrant cat drops in to play with two small children while their mother is out. The verse, composed from only 220 different basic words, has a delightful meter and builds repetitions through devices such as the cat adding object after object to a juggling act. And the drawings, of course, are pure Seuss.

Although the principal character of The Cat in the Hat turns out all right in the end, he is not quite in keeping with most Seuss animals, which are usually gentle, loving, and true blue. Horton, for instance, is a long-suffering elephant who sits on the egg of Mayzie the Lazy Bird through 12 trouble-filled months. And Thidwick is a moss-munching moose who is victimized by an inconsiderate assortment of freeloading friends nesting in his antlers.

“Ted’s animals are the sort you’d like to take home to meet the family,” says Helen. “They have their own world and their own problems and they seem very logical to me.”

Ted first met Helen Palmer in 1925, at Oxford. Young Geisel was studying English literature, seeking a doctor’s degree so that he could qualify for the faculty at Dartmouth, his alma mater. In one of his classes, he found himself sitting next to an attractive young schoolmarm-to-be who kept admiring the flying horses he doodled in the margin of his notebook.

“I was naturally flattered,” says Geisel, “and in a short time the horses were taking up the middle of my notebook, and my Shakespeare notes — such as they were — were in the margins.”

Within a year, Helen Palmer and Theodor Geisel were engaged. Aware that Ted loved drawing better than studying Shakespeare, Helen encouraged him to forsake temporarily his scholarship quest. In the spring of 1927, Geisel returned to his family home in Springfield, Massachusetts. For 10 weeks he drew cats, elephants, bears, and rejection slips. His family was not especially pleased that their son had junked a promising career as an educator in favor of concocting knock-kneed brown bears. On the other hand, Theodor Geisel, Sr., felt partly responsible. After all, as commissioner of parks in Springfield, he had long had a doting interest in the city zoo, where young Ted had often entered the lion cages, and had played with the kangaroos and cub bears.

Toward the end of the trial period, Geisel’s artistic talents finally were recognized when The Saturday Evening Post bought a cartoon for $25. Geisel moved to New York, sold a page of eggnog-drinking turtles to Judge, a humor magazine, and parlayed the fee into a grubstake for marriage.

It was not as Theodor Geisel that he first broke into print. Desiring to save his name for the great serious work he planned someday to write, he adopted aliases such as Quincy Quilp, Dr. Xavier Ruppzknoff, and Dr. Theophrastus Seuss.He finally settled on just plain Dr. Seuss.

It was an early Dr. Seuss cartoon published by Judge late in 1927 that abruptly changed his life. The cartoon showed a knight in bed, with armor strewn about the castle room and a dragon sticking his snout under the covers. It bore the caption, “By gosh, another dragon! And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with Flit.”

The cartoon caught the eye of Mrs. Lincoln Cleaves, wife of a McCann-Erickson advertising executive who handled the Flit account for Standard Oil Company of New Jersey. For three weeks Mrs. Cleaves badgered her husband to contact this Dr. Seuss, whoever he was. Finally weakening, Cleaves agreed. Geisel was signed to a contract, and he quickly created the slogan, “Quick, Henry, the Flit.”

A major crisis arose early in the campaign. Some company officials felt the Seuss bugs looked so sweet and lovable that no one would want to use Flit to kill them. Geisel finally convinced the executives that this was just part of a scheme to overcome women’s natural reluctance to think about bugs. “Quick, Henry, the Flit” became a standard line of repartee in radio jokes. A song was based on it. The phrase became a part of the American vernacular for use in emergencies. It was the first major advertising campaign to be based on humorous cartoons.

But Geisel had to find additional outlets for the stream of his invention. For several years he built up his own fleet, the “Seuss Navy,” as a promotion for Standard Oil’s Essomarine products. He awarded honorary admirals’ commissions in the Seuss Navy to noted yachtsmen, steamship-line captains, and naval officers and presided over a yearly banquet for the group. The Seuss admirals even flew their own burgee—a plucked herring on blue field with red trim.

As an added outlet for his fancies, Geisel dreamed up devices to make a fortune. One scheme was for an “Infantagraph.” It was just before the opening of the New York World’s Fair, when everyone was thinking of ways to make money from the out-of-towners who would swarm out to Flushing Meadows. Musing over these vistas of dollar bills, Geisel envisioned a booth on the midway with a huge sign: IF YOU WERE TO MARRY THE PERSON YOU ARE WITH, WHAT WOULD YOUR CHILDREN LOOK LIKE? COME IN AND HAVE YOUR INFANTAGRAPH TAKEN. Certainly this come-on should bring couples into the booth in droves. There they would be photographed, and out would come a composite picture of their features on a naked baby sprawled on a white bearskin rug.

All that was necessary was to devise a camera which could do the trick. Geisel acquired financing and brought a German camera technician to New York from Hollywood. A camera was built. Tests showed that the project was feasible. However, there were many problems, especially in preventing a mustache from coming through on the baby’s picture. They couldn’t perfect the camera while the fair was on, and the enterprise terminated when the war prevented importation of special lenses from Germany.

“It was a wonderful idea,” Geisel says. “Somehow, though, all the babies tended to look like William Randolph Hearst.”

Yet out of the restlessness of the Flit days, there came a rewarding byproduct. Trying to while away the hours on a long, rough Atlantic crossing in 1937, Ted began composing verses to the rhythm of the Kungsholm’s pulsing engines. “Ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da,” went the engines. “And that is the story that no one can beat,” wrote Geisel. “Ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da-da-ta-da,” went the ship. “If I say that I saw it on Mulberry Street.”

“My contract had nothing to prohibit my writing children’s books,” says Geisel. “When we docked in New York, instead of going to a psychiatrist to get that crazy rhythm out of my head, I decided to illustrate the verses for a children’s book.” After turndowns from several publishers, Geisel interested Marshall (Mike) McClintock, a Dartmouth classmate who was working for Vanguard Press. Vanguard decided to take a chance, and in 1937 published And To Think That I Saw it on Mulberry Street.

Mulberry Street, which relates how a little boy lets his imagination run loose while walking home from school, is today in its 11th printing. It is still in demand at bookstores and libraries, although it must now compete with 12 other Seuss picture books.

Three of them —The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The King’s Stilts, and Bartholomew and the Oobleck — are in prose and have sometimes been compared to the stories of Hans Christian Andersen.

In all his books, Dr. Seuss starts out with a premise so believably fantastic that what follows seems entirely logical. Thus, in On Beyond Zebra, once you admit that the alphabet can extend beyond Z, it follows that the letter Um is for spelling Umbus:

A sort of a cow, with one head and one tail,

But to milk this great cow you need more than one pail!

She has ninety-eight faucets that give milk quite nicely.

Perhaps ninety-nine. I forget just precisely.

And, boy! She is something most people don’t see

Because most people stop at the Z

But not me!The all-time Seuss favorite is Horton Hatches the Egg, which in 1956 sold 15,000 copies, three times as many as when first published in 1940. Horton, a loyal, lovable elephant, gets conned by Mayzie the Lazy Bird into hatching her egg. Horton sits and sits and sits, though ridiculed by friends, frozen by cold, captured by hunters, and finally sold to a circus. When Mayzie returns to claim the egg, just as it starts hatching, it seems that Horton’s faithfulness will go unrewarded. But wait! Coming out of the egg and flying over to Horton is an Elephant-Bird, with ears and tail and a trunk just like his.

And it should be, it should be, it SHOULD be like that!

Because Horton was faithful! He sat and he sat!

He meant what he said and he said what he meant

And they sent him home happy, one hundred per cent.Soon after his first book had been published, the demands on a successful author brought Ted Geisel face to face with a long-standing dread of making public appearances. He was then living in New York and he casuallyagreed to speak at a young women’s college in Westchester, thinking he had ample time to contrive an excuse to get out of it. Unfortunately he forgot the engagement until too late to break it. When Helen insisted that he live up to his agreement, he pleaded sudden illness to no avail. Finally he departed. A couple of hours later, the school called to inquire what was keeping Mr. Geisel. Alarmed, Helen instituted a search. She called his publisher, his friends, then hospitals, but he was nowhere to be found. When Geisel finally returned home, it was discovered that instead of taking the train to Westchester he had hidden out all afternoon at Grand Central Station.

As happens sooner or later with most writers, Geisel has had hit-and-run encounters with Hollywood. During the war, he was an officer with Frank Capra’s educational-film unit and won the Legion of Merit for helping to produce and direct indoctrination films. Shortly after the war, he teamed with Helen to write a screenplay about the rise of the war lords in Japan. The picture, Design for Death, won the 1947 Academy Award for the best feature-length documentary.

In 1951, Geisel created the character of Gerald McBoing-Boing. Young Gerald, whose first words were boing, boing instead of da-da or ma-ma, was originally written for a phonograph record as a satire on parents who fear that slowness in learning to speak indicates a child is dimwitted. The movie cartoon of Geisel’s story won an Academy Award for U.P.A. — United Productions of America — and for Gerald a place in the folklore of America.

In La Jolla, Ted Geisel, citizen, far outranks Dr. Seuss, artist and writer. In addition to his work on the town council and with the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery, he has a special interest. This is to protect La Jolla from Creeping Urbanization. When Ted and Helen Geisel went to La Jolla in 1940, it was a quiet village mostly populated by the wealthy and retired. They bought an old tower on the highest hill and built a house around it. Then came the burgeoning growth of Southern California. Soon they found themselves in the landing path of jet planes, while the town below was invaded by big spenders. A pox of garish neon lights began to blight the community.

While he could not stop the tourist invasion or the jet planes, Geisel has been the prime mover in a campaign to ban commercial billboards and objectionable signs in La Jolla. He even enlisted Dr. Seuss to do an illustrated booklet. In it, two competitive cave men, Guss and Zaxx, engaged in a war to ballyhoo their products, Guss-ma-Tuss and Zaxx-ma-Taxx. Horrendous signs spring up all around, dwarfing their cave sites:

And, thus between them, with impunity

They loused up the entire community.

Sign after sign after sign, until

Their property values slumped to nil.

And even the dinosaurs moved away

From that messed-up spot in the U.S.A.In their tower, the Geisels have a relatively quiet oasis. Their two-acre spot is screened by hundreds of flowering shrubs. Inside the house, all is in perfect order except the den, where Ted spends hours at his drawing board. He loves to draw, but hates to write, and sometimes will spend hours just drawing animals on large sheets of tracing paper. Many of his books, he confesses, have had their start by accident. Horton Hatches the Egg came about because Geisel inadvertently superimposed an elephant over the branches of a small tree he had drawn earlier. So he worked for days trying to figure how Horton could have got into the tree. Then Helen had to figure out how to get Horton down.

The process of turning out a Seuss book is definitely a family affair. “I keep losing my story line and Helen has to find it again,” says Geisel. “She’s a fiend for story line.”

Once the basic idea is set, nearly every line is worked and reworked until both Ted and Helen are satisfied. Geisel’s workroom is always littered with swatches of verses pinned to sketches or taped to a large plate-glass window overlooking the ocean.

All business affairs are run by Helen. Checkbooks confuse Ted, who prefers to count only in large round numbers. Helen also tries to protect Ted from visitors, although in this area she is not always successful. At the slightest provocation, Geisel will halt his work and lead the visitor into the den, where he displays the sketches for his latest book and enthusiastically reads off the verses. There is little doubt that Ted Geisel is himself the first small child for whom he writes.

A few weeks ago, the Geisel household was in one of its “deadline-time-again” emergencies. As usual, Dr. Seuss was in trouble because Geisel couldn’t figure out an ending. He had started off with a wonderful idea — he would do a Christmas book. A bad old Grinch would try to stop Christmas from coming to Who-ville. The suspense had built panel by panel as the little Whos got all their gifts and trees and fixings ready while the Grinch plotted his devilish mission. Then came the stumbling block. How could he end it without being maudlin?

“Helen, Helen, where are you?” Geisel shouted, emerging from his den into the living room. “How do you like this?” he said, dropping a sketch and verse in her lap.

Helen shook her head. Geisel’s face dropped. “No,” she said, “this isn’t it. And besides, you’ve got the papa Who too big. Now he looks like a bug.”

“Well, they are bugs,” said Geisel defensively.

“They are not bugs,” replied Helen. “Those Whos are just small people.”

Geisel retreated to his den to fix the picture and try again with the verses. The dilemma was finally resolved, and How the Grinch Stole Christmas will be published this fall.

On occasion the mother of a young Dr. Seuss follower may wish that the author were less imaginative, especially if her eight-year-old has just ruined two dozen eggs while trying to make Scrambled Eggs Super-dee-Dooper. But most parents consider the Seuss books surefire bedtime stories and are pleased by the hidden gems of wisdom. In Horton Hears a Who, for instance, kind Horton protects the microcosmic inhabitants of a kingdom which exists on a dust speck — “For a person’s a person, no matter how small.” The Whos, about to be boiled in a Beezle-Nut stew because their voices cannot be heard by the outside world, are finally saved when a lone shirker adds his tiny “Yopp” to the united efforts of the citizenry.

And that Yopp, that one small, extra Yopp put it over!

Finally, at last! From that speck on that clover

Their voices were heard! They rang out clear and clean.

And the elephant smiled. “Do you see what I mean?”

They’ve proved they are persons, no matter how small.

And their whole world was saved by the smallest of all!“In our books there is usually a point, if you want to find it,” says Geisel. “But we have discovered that the kids don’t want to feel you are trying to push something down their throats. So when we have a moral, we try to tell it sideways.

Although the Geisels are childless, Ted long ago invented a daughter to vie with the progeny of their friends. Chrysanthemum-Pearl, to whom one of his books is lovingly dedicated, is a comfort to the Geisels, especially when the after-dinner conversation swings around to children and grandchildren. As might be expected, Chrysanthemum-Pearl is a precocious girl who has been able to “whip up the most delicious oyster stew with chocolate frosting and flaming Roman candles,” or who can “carry 1000 stitches on one needle while making long red underdrawers for her Uncle Terwilliger.”

Despite his label as a “children’s author,” Geisel refuses to write down to children. Because of this viewpoint, the Dr. Seuss books are enjoyed by the parents as well as the youngsters. And though contributors to the children’s-book field are often snubbed by the literati, Geisel finally received his reward. One June day in 1955, he was called back to the Dartmouth College commencement exercises.

“Theodor Seuss Geisel, creator of fanciful beasts,” the college president read from a scroll as Geisel walked to the front of the platform. “As author and artist you singlehandedly have stood as Saint George between a generation of parents and the demon dragon of exhausted children on a rainy day. You have stood these many years in the shadow of your learned friend, Dr. Seuss. But the time has come when the good doctor would want you to walk by his side as a full equal. Dartmouth therefore confers on you her Doctorate of Humane Letters.”

Occasionally these days, Doctor Geisel runs into someone who slaps him on the back and says, “Geisel, with all your education, you should be able to do better. There must be some way you could crack the adult field.”

Geisel raises an eyebrow, then smiles. “Write for adults?” he replies. “Why, they’re just obsolete children.”

This isn’t the only time Dr. Seuss has appeared in the pages of the Post. Find out more about him in “The Unforgettable Dr. Seuss.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now