Debra BenAvram’s health woes kicked off with a “really horrible” migraine three years ago. She has no idea what triggered the attack. But over the next six months, it turned into a constant daily headache that forced her home from work each afternoon.

Since then, much of her life has been filled with a myriad of drugs and specialists, two surgeries to relieve neck and head nerve pressure, nausea, acupuncture, holistic diets, fatigue, days in bed. And lots of frustration.

But she’s persevered.

“I just haven’t wanted to cave,” said the 32-year-old CEO of a medical society in Silver Spring, Maryland, outside of Washington, D.C. “For me, I feel like it would be giving up. I have a son, a job I love and care about, and a family. I’m not ready to give up.”

Ben Avram has found some relief, though, thanks to the Diamond Headache Clinic in Chicago and more effective medications. She’s down to 10 to 12 fewer severe migraines a month — cut by more than half. But like many of the more than 29 million Americans suffering migraines, she struggles to keep them under control with a combination of drugs, dietary changes, and other methods.

It’s a daily challenge for 10 percent of the population dealing with this painful and often debilitating headache disorder. More women — one in five — are affected than men (one in 20).

Yet the outlook for migraine sufferers is better than it’s been in years.

Drug research and development for migraine and chronic headache treatments is escalating, with new medications and different forms of drug and nondrug treatments in the pipeline or close to the market.

Among them are skin patches, nasal powders, inhalation devices, a portable transcranial magnetic stimulator (TMS), a surgically implanted stimulator, and the first new class of drugs for migraine prevention in 15 years. Successful clinical trials for some of these new developments impressed experts at the annual American Headache Society’s conference last June in Boston.

“It’s a very exciting period of time for headache drugs. It’s exciting because of the interest of drug manufacturers,” said Dr. Seymour Diamond, cofounder of the National Headache Foundation and one of the pioneers in headache research. He opened the first private headache clinic in 1972 in Chicago.

More than 20 pharmaceutical and biotech companies are in the middle of research or developing drugs and other remedies to treat headaches and migraines. Seymour said the Food and Drug Administration’s approval in 1992 of the first triptan, a drug specifically designed for the acute treatment of migraine, made the drug industry realize a financial market existed for drugs for the long-standing headache sufferer.

But the drug-approval process is a long, arduous one requiring, on average, 10 to 15 years to go from lab testing to the pharmacy. In the end, only one in five drugs tested on humans is approved for the market.

The new potential remedies are coming none too soon for migraine sufferers.

Despite the development of the popular triptans, many migraine sufferers still aren’t getting adequate treatment or the relief they need, according to the recent American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study, sponsored by the National Headache Foundation. It concluded physicians have not dramatically changed their approach to the treatment of migraine in the past 10 years.

“We know that less than half of the people (with migraines) are being treated for migraines at any one time,” said Dr. Stephen Silberstein, neurology professor and director of the Jefferson Headache Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

The drugs either don’t work for them, cause side effects, or people are afraid to take them, experts say.

Triptans are the most often prescribed and most effective drugs in stopping a migraine attack after it begins, according to Silberstein. They work by stimulating serotonin, a neurotransmitter found in the brain, to reduce inflammation and constrict blood vessels. But people with a past history of, or risk factors for, heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, angina, stroke, or diabetes can’t use them.

In the future, Silberstein expects more nondrug options, and more alternatives to injections will be available, both of which will make seeking treatment more appealing.

The first new class of drugs since triptans for the acute treatment of migraines

is awaiting FDA approval now and could be on the market by 2010, he said. A so-called receptor antagonist drug, telcagepant — developed by Merck & Company — blocks the effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) released from nerve endings during a migraine.

“It’s as effective as a class of triptans, but it has no side effects and doesn’t create cardiovascular effects,” said Silberstein. “More people should be able to safety take it.”

Another promising class of migraine prevention drugs essentially calms down the nerve or glial cells in the brain, he said. Research presented at the headache conference shows these cells talk to and regulate each other. During migraine attacks, abnormal activity occurs in these cells. The tablet drug, called tonabersat— developed by England-based Minster Pharmaceuticals—interferes with this process, stopping migraines from developing.

Future drugs, Diamond predicted, should be more effective because they will abort or reverse migraines, and some may actually prevent them, with fewer side effects. Some nondrug remedies may be particularly attractive because they don’t involve any side effects.

One of those, nicknamed the “zapper,” uses a portable electronic device about the size of a hairdryer to administer two painless magnetic pulses that “zap” the neurons in the brain. Called a transcranial magnetic stimulator (TMS), it affects the aura phase before migraines begin when people experience flashes or showers of light, loss of vision, and tingling or confusion: the device is also used for other purposes, such as treating severe depression.

The TMS works by sending a strong electric current through a metal coil, creating an intense magnetic field for about one millisecond. This magnetic pulse, when held against a person’s head, generates an electric current in the neurons of the brain, interrupting the aura before it results in a throbbing headache.

“This is a landmark in the treatment of migraines,” said Dr. Yousef M. Mohammad, a neurologist and assistant professor at Ohio State University, who is the principal investigator of a study at Ohio State’s Medical Center that found the device safe and effective in eliminating headaches when used as they begin.

Last June, Mohammad reported to the American Headache Society that of 164 patients involved in the multi-university, randomized clinical trial receiving TMS treatment, 39 percent were pain-free at the two-hour post-treatment point. That compares to 22 percent who were pain-free after receiving “sham” pulses — due to a placebo effect.

“Since almost all migraine drugs have some side effects, and patients are prone to addiction from narcotics or developing headaches from frequent use of over-the-counter medication, the TMS device holds great promise for migraine sufferers,” said Mohammad.

If the FDA approves the device for migraines, he expects it to be on the market in about six months.

The device sounds worth trying to Patti Salinas, 43, a long-time migraine sufferer from Channahon, Illinois, south of Chicago. “If it’s something that helps and prevents migraines, I would try anything.”

Fortunately, she’s already found some relief, even if not complete.

At age 10, she started having headaches. When she was in her mid-20s, the migraines became debilitating. She’d have four migraines a month, with milder headaches in between from taking lots of over-the-counter drugs.

Her migraines could last six to eight hours and literally put her out of action. “I could do nothing but lay down and put ice packs against my head in a dark room. No sound, no light, nothing that had a scent to it.”

Salinas and other migraine sufferers say people who don’t have migraines usually don’t have a clue about how bad they can be.

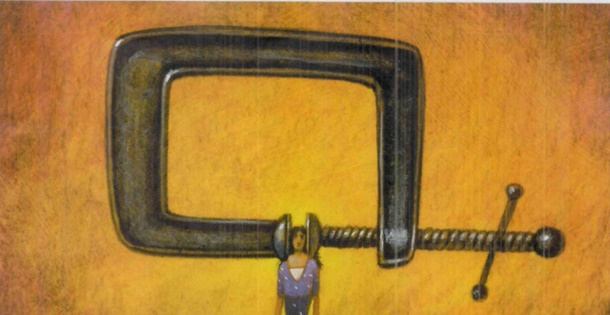

“For me, it’s a throbbing, severe pain in the back of my neck, and it feels like my brain is being squeezed,” she said. “It can even affect your eye sockets so [that] you want to take your eyeballs out and massage them to take the pain away.”

For many like Salinas, migraines interfere with their lives.

She had to leave her office job at a utility company when they’d hit. She couldn’t drive. She’d also have to get childcare for her son. After Salinas relied on over-the-counter and sinus medication, a neurologist prescribed an analgesic with anti-inflammatory properties that helped for a couple years.

But the migraines persisted, so she sought help at the Diamond Clinic five years ago. She learned about headache triggers, kept a log of her headaches, took many tests, and stopped all over-the-counter drugs except ibuprofen. Preventive medications — daily dosages of Inderal and Vivactal — and Imitrex injections she does herself for a severe headache have helped limit her migraines to only one every couple months.

“I still get headaches, but now I know how to treat them,” said Salinas. “I think it’s manageable. My quality of life is better. The severity and frequency (of migraines) have decreased with these preventive drugs.”

For those with chronic, intractable migraines who can’t find such relief, another type of stimulator may be the answer. A study presented at the recent headache conference showed promising results from occipital nerve stimulation (ONS), said Silberstein.

ONS treatment involves implanting a neurostimulator under the skin at the base of the head. The device delivers electrical impulses near the occipital nerves via insulated lead wires tunneled under the skin. People can adjust it themselves.

While the cost isn’t estimated yet, he said the device may be federally approved and on the market within a couple years.

In addition to the potential new drugs and devices, migraine sufferers may get some additional choices with generic versions of existing medications, drugs being repackaged into different modes of delivery, and new combinations of drugs.

Here are some of the options under study, according to the National Headache Foundation:

- Drugs previously used to treat conditions such as epilepsy, depression, and Alzheimer’s may have an impact on headaches and migraines. Ongoing clinical trials involve Aricept, an Alzheimer’s drug; Neurontin, an anticonvulsant; and others.

- A transdermal skin patch contains a drug and a small battery-powered electronic controller that precisely controls the rate and amount of drug released from the patch. A patch using zolmitriptan is in clinical trials.

- A nasal powder form of dihydroergotamine from Britannia Pharmaceuticals may be easier to use and more rapidly absorbed than the current nasal spray form.

- An inhalation device uses heat to vaporize a drug into an odorless mist that passes through the lungs into the bloodstream, perhaps providing relief within 60 seconds. The Staccato device from Alexza Molecular Delivery Corp. is in clinical trials using prochlorperazine.

- Oral and intranasal generic sumatriptan are expected to be available in 2009.

Even with all the promise of new drug and nondrug therapies, experts advise those who experience chronic headaches and migraines to find out and avoid the triggers in their environment and diets that prompt an attack.

A migraine sufferer since age 4, Ashley Etters of Cary, Illinois, has to stay clear of many different foods and scents — caffeine, chocolate, candles, perfumes. Etters, now a 19-year-old Illinois State University student, knows to avoid extended time in the sun and going without eating for too long.

Unfortunately, she’s learned this through years of experience with migraines, causing her to miss a lot of school and interfering with basketball and soccer practices.

“I usually got them for 48 to 72 hours. I was always throwing up with them. I had to sleep in a dark, quiet room or just lay there,” she recalled. “It felt like someone was taking a hammer to my head.”

Now Etters, who takes preventive medications every day, gets a bad migraine about once a month as well as various minor headaches that she’s able to control all the time.

“I don’t think I’m ever going to get rid of them,” she said, seeming resigned to put up with them, as her mother has done for 25 years. Still, she knows how to adapt by taking steps like not falling behind in her studies. If she did, stress would lead to an inevitable migraine.

Stress can also be relieved by other strategies, such as good exercise and massages, and nondrug therapy like biofeedback, say headache experts.

“It’s not a cure-all, but it can work prophylatically in many people because stress is one of the triggers of headaches,” said Diamond, who studied using biofeedback for migraines more than 30 years ago.

Biofeedback is a method that teaches people to control bodily functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension, which were once considered to be beyond voluntary control. Research has shown that by monitoring these functions and feeding back information to people on an ongoing and immediate basis, through visual and auditory instruments, voluntary control can actually be taught.

Using techniques of self-regulation, people can learn to change specific responses of the body, such as releasing muscle tension and spasm, lowering blood pressure, and diminishing headache pain.

No matter what combination of drugs and nondrug therapies they’re using, migraine sufferers often have to stay on high alert — avoiding known triggers but also worrying about attacks they can’t control.

After years of not being able to make definite plans, BenAvram’s life is getting somewhat more predictable. She has responded better to the beta-blocker, anti-inflammatory and antinausea medications she takes. She also knows what to do and not do, eat and not eat.

“You have to wake up at the same time every day,” she said. “I have to eat lunch at noon or I’m going to have a headache at 12:30. I haven’t had alcohol in three years.”

Still, her migraines force her to leave work sometimes. Her scalp is so sensitive, she can’t wear hats, headbands, or tight sunglasses. Her doctor at the Diamond Clinic thinks she’ll always be a headache patient.

“But it’s definitely better,” she said optimistically. “I just try to tell myself, ‘This is a good month or this was not a good month.’ I’ve had two good months in a row. That’s more than I’ve had in the last two years.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now