He liked to socialize and have a good time, but he could just as easily keep to himself. If there was something to talk about, he would talk, but when there wasn’t, as often as not, he’d be out on the back porch of the house listening to the wind in the pine needles, thinking quietly his thoughts as he added twigs to the fire that almost every night he would light. He hardly ever spoke to me about his family, but I knew that he revered his brother and tended to blame his mother for his father’s suicide. Obviously, it wasn’t my great-grandmother’s fault. Being clinically depressed was almost the norm in that family, with a father and two children who eventually killed themselves. For this reason, it must have been easier for my great-uncle Gus to blame someone else for what happened than to come to terms with a kind of genetic curse.

A lot of people thought that he wasn’t as serious as his brother, and maybe it was the clothes that my great-uncle wore, the straw hats, the wrinkled guayabera shirts, or the stained pair of khaki pants that he tied together with a piece of string instead of a belt. Or perhaps it was the Fords that he drove, the secondhand jalopies with balding treads and seats that were more a mix of duct tape and newspapers than of plastic and metal. Certainly rust didn’t faze him. A car was worth keeping only for as long as you didn’t have to spend any money on it, he always said. Or maybe it was just the sheer number of jobs that he’d had, everything from selling schooners in the Caribbean to working as a cook to single-handedly writing and printing a weekly newspaper in the Bahamas.

Of course, it would have been hard to match his brother’s productivity or fame. He was in a different league altogether, but when Gus finally did put himself on the literary map with a bestseller, he blew most of the advance on The Free Republic of New Gondwana, an 8-by-30-foot barge, which he anchored just outside the territorial waters of Jamaica. The platform and the living quarters that he shared with his wife and daughter were the first phase of an island that, eventually, would double as a marine research station and center for international education. As its first president, he issued colorful stamps, petitioned the U.N. for recognition, and minted a set of silver coins with his portrait. His republic, however, came to an abrupt end a few months after its inauguration when a hurricane destroyed it.

Luckily for Gus, his wife had taken the precaution of buying a house in Miami before Gondwana, and what was left of the book deal money disappeared into the Gulf Stream. Their elegant villa on the southern tip of Di Lido Island had Spanish tiles and was painted white, but it was hard to see from the road. Gus didn’t care much for gardening, and the vegetation that grew in the subtropical heat created an almost impenetrable wall around the property.

In the days before my parents separated, I often went to their house, but afterwards, my mother wouldn’t take us there anymore. She was schizophrenic, and her voices had begun to blame Gus for the fact that my father had met and fallen in love with another woman. When I was 13, she had a major breakdown. We were changing houses about once a year, on average, and had just moved into a new apartment in August, but by December my mother’s paranoia had convinced her that the neighborhood was no longer safe. In reality no one but the landlord and our next-door neighbor knew that we were there, but in her mind, there were always people who were out to get us.

She was so convinced we needed to run that at one point she even thought of becoming a nun and letting the Catholic Church worry about the three of us. I told her that you had to be a virgin to pass their entrance exam, but she didn’t think that was something I should joke about and went to mass that night to pray for my soul. She wanted to disappear into the protective arms of Jesus, but when the church wouldn’t let her in, something clicked in her head, and she started to drink heavily. She spent a lot of money on Jim Beam and beer and would drive away in her yellow Volkswagen, never telling us where she was going, and then in the morning, I’d see her weaving down the road towards the parking lot after an all-night binge. Every time she made it back, I was always amazed that she hadn’t killed herself or totaled the car.

I expected the worst when a policeman finally knocked on our door, but all he wanted to know was if there was anyone who could take care of us over the weekend. Our mother had been arrested for drunk driving, and they weren’t going to let her out for a day or two. I told him that we could stay at the house of one of my school friends, and after he looked up the address, he piled us in the backseat of his patrol car. They lived on the other side of town, about 20 minutes from our apartment, and driving over there, we were very quiet. We were all nervous and worried about our mother and trying to make light of the situation. He smiled and then said, “You see all those people out there? They think that you’ve been arrested.” Years later, remembering that day and the ride, I thought about how kind he’d been and how difficult it must be to be a cop.

We stayed with my friend until Sunday evening, and his mother was very generous and bought us enough groceries to fill our fridge before she took us home. My mom was out of jail, but two weeks later, she was stopped again by the police. This time, however, it was my mother’s priest who came to our house to ask if we had any relatives in Miami. Immediately I thought of Uncle Gus, and the priest said that, given my mom’s condition, if no one in the family took care of us, the state of Florida would probably have to put each of us in separate foster homes.

Fortunately, there was never any question in Gus’ mind that we would stay with them. He was not about to let his brother’s grandchildren become the wards of the state of Florida. You took care of your own, and it didn’t matter to him if everyone else in the family thought otherwise. Gus and his wife were hardly what you could call rich, but what little they had they shared with us. In the four years that we were there, they did everything they could to make us feel at home, and while it was certainly an improvement over my mother’s voices and erratic moods, in the beginning, it was hard for me to adjust. I felt as if I had no control over my life and that even the hospitality I’d found could disappear if I didn’t behave. I wanted to be with my father, but that wasn’t going to happen. My mother was still in a hospital, and I couldn’t accept that living with Uncle Gus was the best that I could hope for. I wrote countless letters to my father, begging him to take me away, but he never wrote back, and when I’d finally given up on the idea of ever living with him again, I started to keep a journal, and the journal eventually led to stories — short pieces that I wrote for myself.

I was a skinny kid in 1973, as thin as only a 13-year-old can be, and I remember once hearing Uncle Gus joke that I would never be as tall and as strong as he was. So I asked him what he was like when he was my age. Suddenly, he lost his smile and, with a serious face, said, “Exactly like you.” Looking at me, he must have seen himself, a shy and introspective young man.

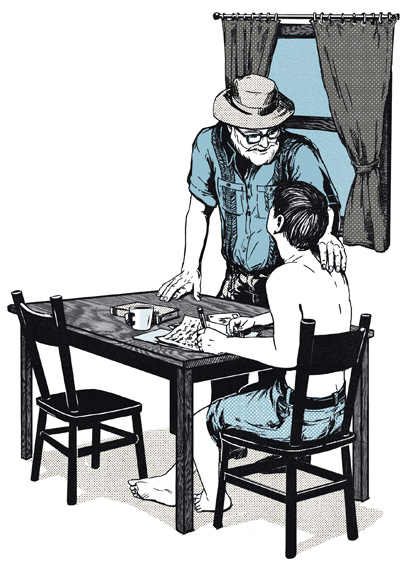

He knew what I was going through. His own father had killed himself when he was about as old as I was, and because of the financial disaster that his mother had been left with, he was sent to live with a sister and her husband in another part of the country. He never told me about this, but once when I was writing in the dining room of their house, and this was August, and it was very hot and humid, and I was wearing nothing but a pair of khaki Bermuda shorts, shirtless, and without any shoes, Uncle Gus came up behind me quietly, and he put his hands on my shoulders and said, “If there’s any truth in what they say that an unhappy childhood makes for a great artist, then you’ll go far, Mike.”

He said nothing else, but that was enough. Coming as it did from my uncle, I think that I have never received or ever will receive as great a compliment in my life. He taught me everything I know about generosity and sacrifice. He could never give me much, materially, but in his own way and through his actions, he showed me what was important in life.

Four years after I’d left their house, my Uncle Gus’ diabetes had deteriorated to the point where his doctors were going to have to amputate both his legs. Not wanting to be a burden to his family, he put an end to his life.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Ah, John…your writing has that touch of soul that reaches into all our memories and makes us feel with you.

Hemingway On Stage is proud to know you and delighted to be able to read your fine work. I eagerly await a new book and I look forward to our next

meeting.

Brian: http://www.briangordonsinclair.com

The author conveys emotion well.

Prose that manages to touch or disturb the reader–preferably, both–is good writing. .

And John, when you can put that emotion between the lines, you’ll have reached the very highest plateau.

Highly readable, with a tinge of sadness. But as short fiction, it is rather short. The story should have been developed further with a lot more about the years spent with Uncle Gus. Merely mentioning his generosity is not sufficient; it should have been illustrated with anecdotes from John’s life with him. In its present form, it ends abrubtly and rather disappointingly, as the writer had led one to a high degree of involvement with his easy though touching narrative style.

John,

Really enjoyed the short “fiction”. Must have been hard to write about that time in your life. As a big fan of your grandfather, would like to able to say he would have enjoyed it…but who knows? I am anxious to read more of your work. Thank you for this.

Chris

Great, John! I love it and I hope you do more. It’s touching, a moving sadness with flickers of gentle humor so that we love these characters – Mike and Gus – as they evolve toward that wonderful moment when Gus puts his hands on Mike’s shoulders. Lesley

Hola, I really enjoy the way you write Brother.

In fact, I find it very inspirational and brings back child hood memories of the creative writing I have done.

That being said, I did write this comment to you which was longer and of a story thay had great impact on me, 4th grade and then attempted to post it to you. A message came back saying Java script and cookies needed to be enabled to do so. Tried everything I know and still, no go. Perhaps I will rewrite it and send it to you in another form.

I understand the folks of San Fermin’ want you at fiesta this year, Good for you, they are wise to take care of you.

Only wish from here and I know I’m not the only one is, that we could all be there with you.

Take care Brother, “GORA!!!”, Fan Fermin’

BFAM, michael