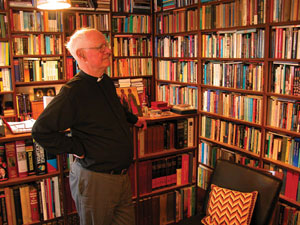

John Polkinghorne remembers the day when some of his colleagues thought he had lost his mind. He was already famous as a physicist at Cambridge University for his work in explaining the existence of quarks and gluons, the world’s smallest known particles. He had won heaps of awards in his 27 years there, including membership in Britain’s Royal Society, one of the highest honors that can be bestowed on a scientist.

It was the end of the academic year, and he had invited some colleagues to his office for a meeting. At the conclusion, they gathered their papers, ready to leave. “Before you go,” Polkinghorne said, “I have something to tell you.”

The audience settled back into their chairs. “I am leaving the university to enter the Anglican priesthood. I will be enrolling in seminary next year.” Stunned silence filled the room for several seconds until one of his colleagues, an atheist, finally uttered what was probably on everyone’s mind: “You don’t know what you’re doing.”

A few others were supportive of his personal choice, but there was a muttered consensus that this beacon of the scientific world had just committed intellectual suicide.

Can religion and science co-exist? Many would say no. Science, after all, deals with what can be measured, tested, and verified. Religion deals with things that can, by definition, only be taken on faith. Today, John Polkinghorne inhabits both worlds, but he understands why this is confusing to some.

“When you say that you’re a scientist and a Christian, people sometimes give you a funny look, as if you’d said, ‘I’m a vegetarian butcher.’ Many people out there think science and religion are actually at war with each other, but I believe that science and religion are friends, not foes.”

Science and religion are not mutually exclusive, Polkinghorne argues. In fact, both are necessary to our understanding of the world. “Science asks how things happen. But there are questions of meaning and value and purpose which science does not address. Religion asks why. And it is my belief that we can and should ask both questions about the same event.”

As a for-instance, Polkinghorne points to the homey phenomenon of a tea kettle boiling merrily on the stove.

“Science tells us that burning gas heats the water and makes the kettle boil,” he says.

But science doesn’t explain the “why” question. “The kettle is boiling because I want to make a cup of tea; would you like some?

“I don’t have to choose between the answers to those questions,” declares Polkinghorne. “In fact, in order to understand the mysterious event of the boiling kettle, I need both those kinds of answers to tell me what’s going on. So I need the insights of science and the insights of religion if I’m to understand the rich and many-layered world in which we live.”

Seeing the world from both the perspective of science and the perspective of religion is something Polkinghorne describes as seeing the world with “two eyes instead of one.” He explains: “Seeing the world with two eyes—having binocular vision—enables me to understand more than I could with either eye on its own.”

Polkinghorne was just 47 when he left Cambridge to become a priest in the Anglican Church. The year was 1979. The reason he left his physics post was multi-faceted. He had been part of a neighborhood Bible study and wanted to participate more in the sacraments at his church. Plus, he was ready to move on. “I had done my bit for physics,” he asserts, “and, unlike some other things in life, one doesn’t necessarily get better at physics the older one gets.”

After being ordained, he first served in the village of Blean, just up the hill from Canterbury Cathedral. At first parishioners were leery that this towering intellect would be difficult to understand. But Polkinghorne soon won them over with clarity and reason (that metaphor about the boiling teapot is recalled by one church member), and so his presence was welcomed into the community. In 1986, he returned to Cambridge, first as a chaplain to one of the colleges and eventually as president of Queens’ College, a position he held until he retired in 1996.

Over the years he has preached his unique “binocular vision” theory to explain how a person committed to scientific inquiry could also be committed to the teachings of the Bible. He’s written many books on the harmony of religion and science, served on boards concerned with ethical standards for medical research, and received numerous honors. For his contributions, Polkinghorne was knighted by The Queen. (As a priest, however, he cannot be addressed as “Sir Polkinghorne.”) He’s also a highly regarded public speaker, putting into words a philosophy that is so moderate and reasonable that it was bound to make enemies on both ends of the religious spectrum.

Religious fundamentalists—those who believe in a six-day creation, a literal Adam and Eve, and an earth that is 6,000 years old—tend to repudiate Polkinghorne’s acceptance of evolution, the Big Bang, and a universe that is billions of years old. Bill Hoesch, curator of the Creation and Earth History Museum in Santee, California, derides Polkinghorne’s beliefs as “idol worship.”

Hoesch doesn’t see how scientific theory can enter the picture when the subject is the miracle of creation. “Is [Polkinghorne] just wrong? Yeah. He’s been deluded,” says Hoesch. (Polkinghorne actually toured Hoesch’s museum last November. While there, he stopped at a poster that claimed there was no suggestion of death in the Bible until the sin of Adam and Eve. “It may not be in the Bible, but the evidence is everywhere else,” Polkinghorne said, shaking his head.)

On the other extreme, atheists don’t exactly cotton to his ideas either. “In the very difficult context of theoretical mathematical physics, John made a real contribution,” allows Steven Weinberg, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist from the University of Texas who is also Polkinghorne’s friend and debating partner. “As for his religious interests, I’m sure he means well, but I don’t find his search for common ground a good thing. There is a relationship between science and faith, I suppose, but science tends to weaken faith.

“I don’t want to see John go away,” Weinberg adds, laughing. “Just his beliefs.”

Religion doesn’t have all the answers, Polkinghorne agrees. He points out that magical Biblical explanations for lightning and plague were long ago debunked by science—and that the problems were solved with lightning rods and rat poison. “That’s one of the ways science has been helpful to religion,” notes Polkinghorne. “Religious explanations make mistakes, and science helps us see that some things are a natural phenomenon. That’s helpful to religion. Truth is very beneficial to both sides and helps both see more clearly. It helps and corrects some mistakes. But that doesn’t mean all religious belief is a mistake.”

And therein lies the key to Polkinghorne’s uniqueness: He addresses challenges—even rude ones—from both sides with such grace that it’s nearly impossible to be angry with the man, whatever your point of view. “There is no one else in the world like him,” said Darrel Falk, biologist, president of the BioLogos Foundation, and author of the book Coming to Peace with Science. “He is the best representative of the dialogue between faith and science because he has struggled with—and achieved so much in—both fields. He’s the most respected voice out there.”

As to the question of which has the clearer view of reality—faith or science?—Polkinghorne answers that it’s a false question. “You have to be two-eyed about it. If we had only one eye, then we could say it’s religion, because it relates to the deepest value of being human. Science doesn’t plumb the depths that religion does. Atheists aren’t stupid—they just explain less.”

Polkinghorne thinks atheists fail to consider the possibility that there might be more to life than what we can see and test and verify—that life might have transcendent and ultimate meaning. In addition, Polkinghorne argues, atheists have faiths of their own—beliefs that aren’t visible, testable, or verifiable any more than religion is, yet they inform one’s point of view in a manner similar to religious faith.

Ultimately, people of faith should not be afraid of science because both pursue truth. “Because people of faith worship the God of Truth, they should welcome truth from whatever source it comes,” Polkinghorne says. “Not all truth comes from science, but some does. It grieves me when I see Christian people turning their backs on science in a willful way, not taking seriously the insights it has to offer. All truth interacts with each other, and all truth is helpful.”

Likewise, people of science do not need to be afraid of faith. “Science doesn’t tell you everything. Those who think it does take a very diminished and arid form or view of life.”

For Polkinghorne, science made his faith stronger, and that faith made him a better scientist. Both approaches fulfill one of his favorite verses in scripture, I Thessalonians 5:21, which the esteemed physicist paraphrases: Test everything. Hold fast to what is true.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’m delighted that more and more scientists are turning to God and religion. However, I am flabbergasted why these highly intelligent people, who are steeped in the methodology of the scientific method, would choose to do so by becoming Christians. I just dont get it. Whether it is John Polkinghorne, Francis Collins, Sy Garte, Robert Melnichuk, Tom Rudelius, or Rosalind Picard, why do they all jump on the default bandwagon and adopt a Faith that is so old and corrupted and has no chance of helping mankind move forward? Dont get me wrong, I readily accept that the pure teachings of Christ were revealed to him by God, and for the individual they still can promote spiritual growth. But while “the core of religious faith is that mystic feeling which units man with God”, religion serves a second purpose which is “to carry forward an ever-advancing civilization”. Christianity was vital 2000 years ago, but is now a zombie. Why didnt they investigate fully into all religions in order to find one that could accomplish both? Perhaps they would have discovered that the Bahá’í Faith, which is only 180 years old, is ideally suited to meet the spiritual and societal needs of the current age. It promotes the unity of all humanity, recognizes that all religions have come from one God, has as its first principle the independent investigation of all truth, recognizes gender equality, pursues the goal of world peace, calls for universal compulsory education, and declares that science and religion are in essential harmony. It is currently engaged in a world-wide program of community building which is based on the adoption of spiritual principles that build the necessary human resources to foster service to humanity and common worship. It is found in every nation and territory. Its original teachings were revealed by its author, Bahá’u’lláh, and still exist in their original form. It has no clergy, but is guided by democratically-elected institutions at all levels. Come on, scientists, hold for the same standards in religion as you did in science!

Degrees and diplomas now dictate the qualifications for a theologian. Therefore theologians think they are scientist yet declare that existence is not physical.

Scientist however are qualified by their degrees and diplomas yet fall short of declaring that existence is physical. The truth lies not in available volumes of knowledge rather beneath their feet.

The hallmark of a scientist that has given up – turning to God. History is littered with great minds that reached an impasse and simply gave up, like John Polkinghorne.

Newton himself gave up on science after writing his “Principia Mathematica”, he placed the planets in their right locations but gave up on figuring out what caused their movement, etc. – that was the domain of God. After which Newton completely abandoned science and turned to writing religious tracts, and other non-scientific endevours.

John Polkinghorne’s case sounds eerily familiar.

Religion is indeed man-made and as such, is flawed. Spirituality, that sense of being part of something greater, however, is universal, and I think it can entirely complement and enhance the advances made in science. Religions are merely various pathways to the same source, which lies beyond anything man could ever find, solve, or understand. That peace which surpasses all understanding. Science seeks truth, and so does spirituality. Both are noble endeavors and serve the advancement of humankind. I hope that one day man will evolve to a point where specific religions, which divide us by boxing and labeling things according to the cultures who created them, are no longer needed to access spirituality.

To believe in a given religion, which takes for granted the existence of a deity, requires the suspension of what makes us human, Reason. All religion was invented by man, based on superstitions, ignorance and prejudice…and perhaps as a way to dominate people. Science may not have all the answers, life and the universe entail misteries that our imperfect intellect may never grasp…but at least in theory, everything has an explanation, and science may follow some day. MM.

It seems to me that science and faith are like space and time. They are two sides of the same substance. You can have all one, all the other, or some combination of the two. A sort of dualism, if you will.

I like Anglican’s view: “God creates, science explains.” But isn’t there more to it than that? Religion is a quest for God, is not science also rooted there? We want to understand how the world works, not only to create technology and made life easier, but also to answer the ultimate questions we have been asking since our ancestors roamed the plains of Africa.

Who are we? Why are we here? And most importantly, what is this force that drives and connects us? Before we could answer those questions with science, however, we need to understand the basics, like “how can we get a steady food supply, free ourselves of disease, and secure shelter.” Once we know how to do that, we can devote ourselves to the ‘big’ questions.

It seems that somewhere along the way, science forgot that. But just because one cannot use science to find God today, does not mean that we will not be able to do it tomorrow.

“Ask and ye shall receive.”

“religion demands blind obediance”: No it doesn’t.

“Come now, let us reason together,” says the LORD. – Isaiah 1:18

And also

“Look around in wonder, because I’m doing things right now you wouldn’t believe even if I told you…” – Habakkuk 1:5

I wasn’t raised to accept my God unquestionally or any of my other beliefs unquestionally. My reason and my science doesn’t contrast or attack my faith and my religion, but rather informs it. This belief you have of the antagonism between science and religion isn’t based in science.

“Humanity is abandoning religion, and gaining peace.”

And that isn’t a statement grounded in or provable by science either, but it is in fact a form of historcism. You have faith in your conviction that your great loves of Science and Reason will triumph over the darkness of ignorance and usher in a glorious age of peace, but this is conviction which is itself not grounded in Science and Reason so is itself evidence that overthows itself. For there is reason to hope that Reason will bring rationality and peace to man, if you yourself are so easily swayed away from it into the belief in a materialistic Eschaton. And indeed, there is no reason to believe from the evidence of history, which though itself is not a science ought to at least count for something, that societies that have abandoned religion (or more specifically, a belief in God) have replaced it with something better.

I admire Polkinghorne for not abandoning reason and observation of the natural world. However, it distresses me to see that a person of his intellect believes, completely without credible evidence, that a man who died over two thousand years ago will one day return to judge us all.

What is science is observation and repetition? No one was there to observe the beginning, so science is left with only theory. Science is unable to create matter from nothingness so there can be no repetition of the event. I have no need for man’s scientific wisdom to validate the word of God. I stand in faith, in the precious scriptures and simply don’t worry what the World may think. Yes, faith can be that simple!

@Joel “…religion demands blind obedience…” Is this really the case? Some groups yes definitely, but in my experience as a scientist and minister, that has not been my experience of Christian churches and believers or those of other faiths. Reason, experience, reflection and critical choice are part of the spiritual disciplines of most of those who I have been associated with over the years. I certainly don’t demand blind anything from the members of my congregations.

God created everything. Of course God and science can co-exist. I’m not a creationist. I believe the “theory” of evolution helps explain things. God can create in 7 twenty-four hour days or 7 sixty second days or 7 geological epochs whatever. God creates, science explains. When science gets it wrong it trys again. “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”

But which of the thousands of the earth’s religions should you accept in tandem with science? Science is refutable, but religion demands blind obedience, often even in defiance of evidence. We have a more reliable, less hysterical, way of examining the world with science. Humanity is abandoning religion, and gaining peace.

Accept faith and acknowledge truth then walk hand in hand woth God and Science this way you will be whole and enjoy life more fully.

Finally a scientist who is not afraid to go where the evidence leads.