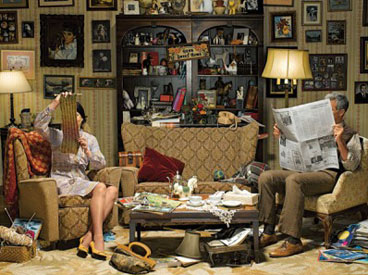

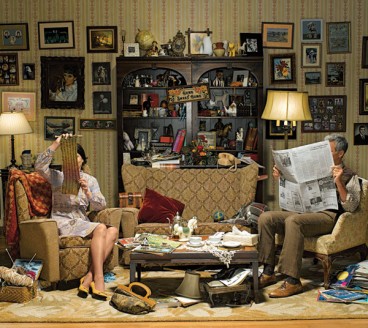

For some time the least-used part of our house, the basement, had been the cause of the most stress. Strewn about and packed into the sectioned spaces—a finished playroom with two storage rooms on either side with exposed cinderblock walls—were baby furniture and toys, car safety seats, obsolete electronics, boxes of books, cans of paint, camping and sports equipment, bags of jumble, and three boxes containing the entire written and photographic archives of a deceased wing of my mother’s family.

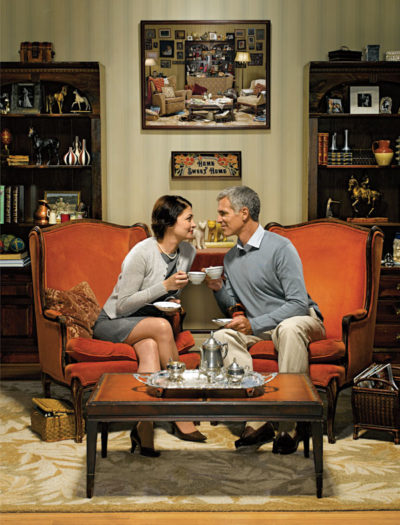

I was all for eBay and turning old stuff into cash, but neither my wife nor I could work up the enthusiasm to act on this idea. The cluttered space below the stairs where neither of us could bear to go slowly began to develop into a field of conflict. The two of us are of a single mind about many things—about most things—but we realized that we differ on stuff. It took us a while to realize this, but one day as we were struggling (okay, arguing) about the functionally cordoned off no-go zone down there, it hit me: I was a hoarder; she was a stockpiler.

There’s a fine distinction. As a hoarder, I can never let things go, sensing either sentimental or monetary value in items that are notable to my wife only because they occupy valuable space. I had boxes of postcards people sent me in the 1980s. I kept computer cables. (Hey, you never knew when they might come in handy.)

As a stockpiler, my wife is a member of a different species entirely. The stockpiler always buys more than he or she needs, then justifies it in economic terms. Buying in bulk saved my wife from having to make multiple trips to Costco and Trader Joe’s, she explained. I understand the argument perfectly when it comes to paper towels, toilet paper, and lightbulbs, but it didn’t explain what looked to me like a lifetime supply of chocolate sauce. The reason for that, she said dismissively as if I were missing the whole point, was that she bought more after forgetting she’d already stockpiled a goodly amount a few months earlier.

Consider the types, though. One is focused on what’s past, the other on the future. So we came to see the basement as being divided between my urgent desire for historical preservation and, well, her grand vision. Or to put it another way, between my junk and her supplies. (“Not my supplies,” she would say, “our supplies,” since I too would use the stocks, including, naturally, the chocolate sauce.)

We agreed we needed to address it, but because it was out of sight we just let it grow. To an outsider, it might have seemed as if we were nurturing an indoor junkyard.

Then I got into a conversation with Richard Lyntton, who had a business to help people deal with their clutter. Lyntton developed his thinking during five years of sharing space with fellow soldiers in the Royal Tank Regiment. “When you’re in such a confined space, it forces you to consider what you truly need,” he told me.

Lyntton sees clutter as more than a matter of just, well, matter. “Most people think of it purely on a physical level,” he said, “but clearing physical clutter is a good place to start clearing your whole mental and spiritual deck. What matters ultimately isn’t the thing itself but that you have a feeling of peace.”

As far as my historical preservation project was concerned, he suggested loading a rented truck and dropping it all at a local thrift store. “Just get rid of it,” he said. “It’s all dead energy. You’ll feel great once it’s gone.”

And so I determined to address the mess. Taking Lyntton’s advice not to procrastinate, I went to the basement without so much as a pit stop at the fridge.

I went down deep. Real deep.

There were photos, letters from an old girlfriend, schoolwork, and stories and diaries that I felt vaguely embarrassed to read now, as if I were sneaking a peak at someone else’s private life. Other objects, too, cued remembrance of things past, and the experience of poring through the stuff seemed to telescope events, making them appear closer than they had been in years. An old typewriter took me back to my first ambitious—if grandiose—days of writing, blazing away in the basement of my parents’ house.

The act of disposing became by turns emotional, sentimental, and then, finally, cathartic.

Lyntton was right that all the stuff wasn’t just stuff, but it wasn’t “dead” at all. It was a record. Events and relationships had run a course with a beginning, middle, and end. People had married, borne children, divorced, and died.

“If I knew things would no longer be,” says the narrator at the end of the Barry Levinson film Avalon, “I would have tried to remember better.”

I scored my vanity a few times, too, with photos that were like time-lapse shots for a PowerPoint presentation on aging. Which pushed me toward another thought: Where have all the years—my years—gone?

The fear of the future, the unknown, is common enough, but what spurred my fear of the future was how quickly the past had passed. Childhood passes under the pressure of anticipation, slowly while it’s in progress, but as a parent, at least for me, the years have seemed to float up and burst like bubbles. The past was contained in finite objects, and they reminded me of the finitude of time.

Of course, there’s a practical side to it all, too. If the objects help you remember and, so, give a certain shape to your life, they have a totally opposite impact on your digs. They accumulate, time stuffed into a space. A brave few pay $100 an hour to get walked and talked through the process of divesting. Some people are forced to deal with it at certain times, such as when they move or when the spirit moves them, but it’s inevitably left to the people who bury the dead to toss out their junk as well—and to wonder why the heck anyone would keep thus-and-such.

My afternoon of purging passed quickly. The garage filled with stuff that I vowed I would soon take away to the thrift shop or the dump. My wife came home. “Wow,” she said, “you really did some job. You look tired.”

“I feel all cleaned out,” I said.

She surveyed the basement, the cause if not the scene of a few battles. Enough space had been reclaimed that we could find a meeting place somewhere in the middle of the room to start armistice talks. She considered the open space.

“I’d say it looks like we’re about halfway there,” she said.

“I was just thinking the same thing.”

Spring Cleaning Magic

Three rules that will completely change the way you think about clutter—and make it easier for you to let stuff go!

Cleaning house is not just about clearing away the stuff, the experts say. It’s about clearing your mind. The less stuff you have, the more space you have to think. Whole books have been written about cleaning away clutter, but the following principles will save you hours of time (and much agony).

• The Six Month Rule: Start in your bedroom and take out every object and article of clothing, says Donna Smallin, author of nine books on eliminating household clutter. Then, one by one, pick up each thing and ask yourself if you’ve used it in the past six months. If you have, put it back. If not, put it in the discard pile. Advance to the next room. Repeat.

• The Irreplaceable Objects Rule: Some things—such as vital papers and photographs—can’t be thrown out. Consider scanning paperwork and photos and saving them on your computer. Of course, computers can add another significant layer of clutter. Both the Windows 7 and Apple Lion operating systems will save your files on an external hard drive, and various programs (such as Lucion Technologies’ FileCenter, $49/year, and Carbonite Home, $59/year) allow you to archive material in a way that you can store it safely and out of the way.

• The Re-sale Rule: What do you do with the stuff you’ve cleared? Richard Lyntton, our declutter expert, said that trying to make money from it is a mistake. It takes time and a level of commitment that takes you, once again, back to the past from which de-cluttering is meant to liberate you. You’ve already used what you’re getting rid of, so now it’s time to give it away and let that energy go. Pass it on to a local charity or, better still, someone you know who needs it.

Spruce Up Your Home in Minutes

Tactics for emergency cleaning on short notice.

Your friends and family would never just drop in without calling. Except, of course, when they do. Let’s say an old friend or one of your children has phoned that they “just happen” to be in the area—meaning they didn’t want to plan a lengthy get-together but now they want to drop in and be watered or fed.

No, they don’t just want to go to a restaurant. Slight problem: Your place is a mess. You were going to clean tomorrow, but there’s no time for that now. What do you do? Here are some quick-clean tips that will help get you out of a jam.

• Make a Point of Odor. Spray air freshener around. Not too much!

• Clear the Decks. Find an empty box or laundry bin—anything!—and start tossing in loose clothes, candy wrappers, damp bathroom towels, dirty dishes, and the like, writes Sarah Aguirre, on about.com. Fill it up and stick it in the back of the closet. Don’t try to clean the whole house. Just target the most important areas. Where are you going to be hanging out? Living room? Back porch? Hit up these areas and leave the rest.

• Wipe Clean. Spray a rag with a cleaning solution such as 409 or Fantastik if you have it handy (dish soap if you don’t). Wipe down kitchen surfaces first, then bathroom, and finally the dining room table.

• Freshen Up Your Self. Aguirre points out that your visitors are not coming to see your house, really, are they? They’re coming to see you. Look in the bathroom mirror. Brush your hair. Check your clothes. Women, freshen up your makeup; men, if you haven’t done so already, shave.

• Divert Attention. Use something colorful—a plant or a bouquet of flowers or string of Christmas lights—to distract your guests from the less-than-perfect state of your home, says Frayda Kafka, a hypnotherapist based in Lake Katrine, New York. “I throw a brightly colored dish towel over my dishes. Someone looks in my kitchen, they see the red thing and they don’t notice anything else.”

• Dim the Lights. Another way to distract, according to Kafka: Light some candles if you have any. Nothing hides imperfections better than low lighting.

• Finally, Don’t Apologize. “When you do that, you simply call attention to the imperfections that most people wouldn’t notice in the first place,” says Kafka. The house or apartment won’t look perfect, sure. But, this is a triage situation: You are simply striving to make it look presentable.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I so enjoyed reading this story that I lost my head and immediately posted it to Facebook, with this comment: Somehow, this looks familiar to me. Oops. I think I’m in trouble!