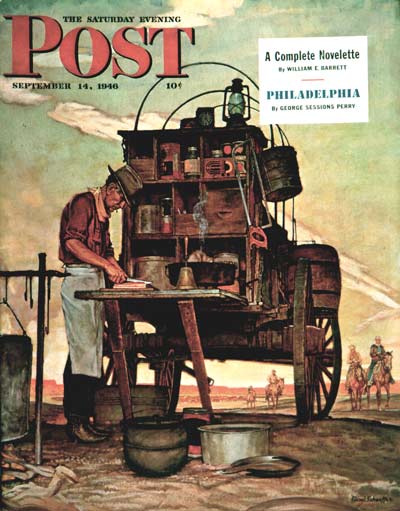

from September 14, 1946

Mead Schaeffer painted 46 covers for The Saturday Evening Post, and behind them often lurked intriguing tales.

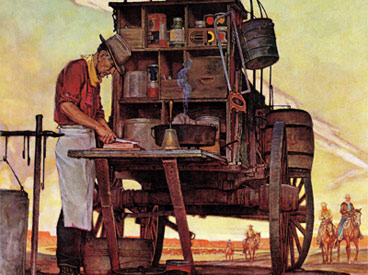

A writer accompanied artist Mead Schaeffer out West in 1946 and found that “making one of these covers is a fairly complicated project, not unlike the shooting of a movie.”

“The LX ranch, near Amarillo”, Post writer Lewis Nordyke wrote, “covers some 75,000 unplowed acres, and has been used as a cattle range since the days of the Plains Indian, with never a complaint from the cattle.”

But when cover artist Mead Schaeffer set out to paint a chuckwagon scene, he “took a thoughtful look at the range and said it wouldn’t do for his purposes. The trouble with the range, he said, is that it didn’t look like a range.”

This puzzled “Dad” Robinson, who had been the ranch cook for almost sixty years. “If this don’t look like range, I’d sure like to know what range looks like.” The artist explained that sometimes “the real thing isn’t always paintable.” Schaeffer continued, “But it doesn’t matter. We can roll out the chuckwagon…and pick up the range somewhere else.” That’s the illustration business.

“His business,” the old cook was overheard to say, “Must be durned peculiar.”

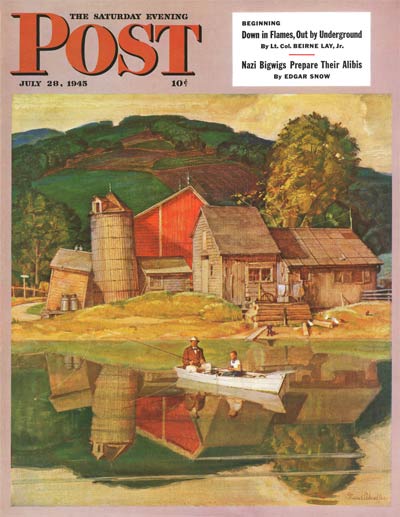

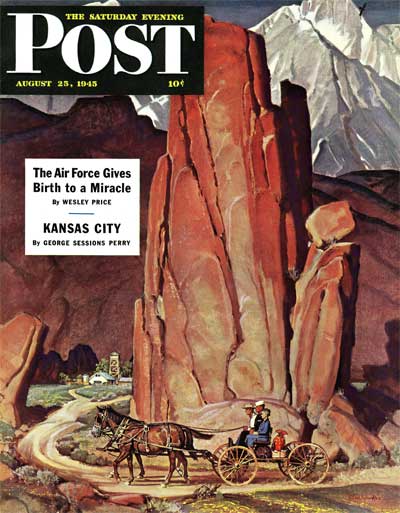

from July 28, 1945

In the mid-1940s, Post editors were running a series of covers as a sort of regional album of America, and readers never knew what part of this nation’s majesty they might view next.

Often the artist would have to do a cover months in advance, painting, say, a Christmas cover in June.

But this time, Schaeffer told editors, in August, “I started out for a day’s fishing on Schoolhouse Pond (Cambridge, New York), telling myself I would concentrate on my next assignment, a New Year’s Eve cover, as I cast for bullheads. The lure of a drowsy summer day did the rest,” and he painted this summer cover…in summer!

Post editors once described Mead Schaeffer as a fisherman who happened to also paint. The artist/outdoorsman was so enamored of the sport he moved from New York to Vermont after meeting Norman Rockwell, as this story by Holly Miller in a 1979 issue states:

from May 19, 1951

“I had no intention of moving from New Rochelle,” explains Schaeffer. “But when Norman and I finally met at that party, he mentioned he had just bought some property on the Batten Kill River in Vermont. I said, ‘You mean you’ve got a place on the greatest fishing river in New England?’ We went up before he even installed the heat.”

“Just before this picture was painted,” Post editors wrote of this 1951 cover (left), “the man was calmly trying to feed the trout another variety of fly and they were calmly ignoring his hospitality.

Suddenly, a countless family of Green Drake ‘nymphs,’ which previously had risen to the surface of the water to hatch, discovered that they had wings, and decided to zoom into the wild blue yonder.”

And to drive fish and fisherman alike crazy. The angler is attempting to tie an artificial Green Drake to his line.

Rockwell and Schaeffer became neighbors and close friends. They shared models. Rockwell’s sons would show up in Schaeffer paintings, and Schaeffer’s daughters in Rockwell’s.

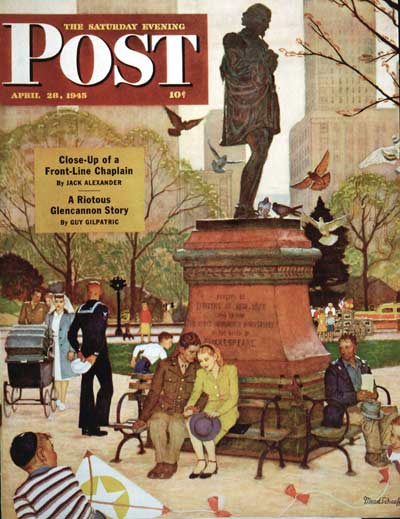

from April 28, 1945

The two families even traveled together, and Rockwell accompanied Schaeffer on many fishing trips. As he would be the first to admit, however, Rockwell was not much of an outdoorsman. Even though they fished together, Schaeffer joked: “Norman was lousy at it.”

Speaking of Schaeffer’s daughters, they appear in this painting. One is the young lady being romanced under the statue of Shakespeare and one is a nearby nurse. Schaeffer had to paint the Central Park scene twice.

Editors noted: “The first attempt, made in the thirty-two degrees below zero weather of Vermont, was ruined when the white-lead sizing used to prime the canvas froze and the paint flaked off.”

Would you believe the heavens once had to be scrambled for a Post cover?

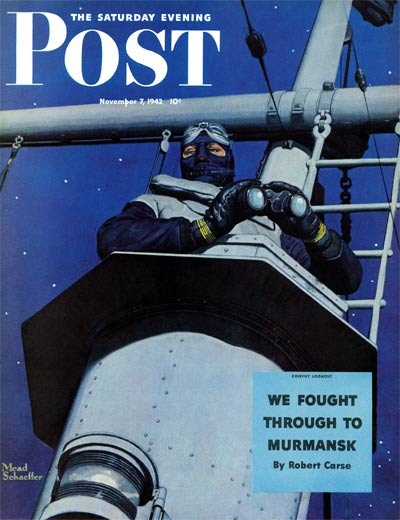

from November 7, 1942

Schaeffer painted a gritty and realistic series of covers during WWII. The Navy found the first version of this cover a bit too realistic and asked the artist not to use it.

They felt the enemy might be able to calculate the Russian convoy route from the formation of the stars. The artist felt he owed it to the fighting men to strive for authenticity, but promptly reshuffled the constellations.

The Navy supplied the equipment and model depicted for this view of the crow’s nest of a PC boat. To get the personal feel of the scene, Schaeffer had a long talk at the New York Navy Yard with seamen who had stood the watch.

“The time of night portrayed,” the artist noted, “is the most dangerous and vulnerable in which to operate, as it is clear and starlit and the ships form silhouettes, making them perfect targets.”

from August 25, 1945

As in the case of the “Farm Pond Landscape,” this scene was meant to be a vacation for the artist. But it turned into another busman’s holiday. While in California, Schaeffer drove out to Lone Pine to see unusual rock formations.

He was quite content to admire this strange rock when darned if a buckboard didn’t come rolling around the bend. Perched aboard were a man, a woman, and a sailor. The sailor especially caught his eye.

“He was a big, rawboned youngster, obviously built for the saddle instead of a uniform.”

Thus, wrote Post editors of this 1945 painting, “Schaeffer’s breathing spell evaporated and he began to make sketches for another Post cover too good to pass up.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Interesting and enjoyable piece, Diana. Thanks! If you’d like more stories, my mother is Mead’s niece, owns several of his paintings, and knows lots more stories. Let me know if you’d like her contact info — I’m sure she’d be happy to chat with you.