This is the second installment of our six-part series on the lead up to Gettysburg. Click here to read part one, “The News from Gettysburg: A Hazardous Move.”

The news reached Philadelphia on a bright June morning in 1863; Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army had invaded Pennsylvania and was heading virtually unopposed to the state capitol. Suddenly, a Post correspondent wrote, the city was filled with a militant spirit.

“One could scarcely turn in any direction without meeting with a fife and drum. Recruiting officers were constantly marching up and down the streets. Large four-horse omnibuses, with bands of music and placards announcing various [assembly points], were driving about the city.

“The apathy, that for a time had seemed to taken possession of the community, was speedily dispelled. The possibility that the rebel horde might reach the Susquehanna, and even cross that stream and destroy our state capitol, was freely entertained yesterday; but there was also a firm resolve, ‘that many a banner should be torn, and many a knight to earth be borne’ before that disgraceful calamity should befall the state.”

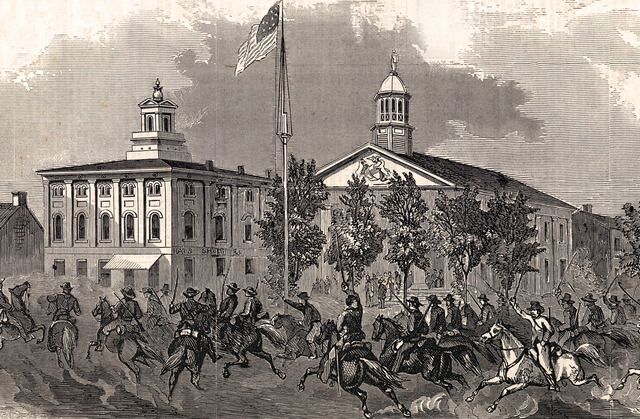

In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania—100 miles closer to the approaching Confederate Army—the mood was quite different. There, residents had panicked after hearing that the rebel army had looted Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Swarms of frantic passengers gathered at the railroad station, desperate to fit into any railway car they could find. The roads out of town were choked with wagons piled high with household effects, bearing families away from the enemy, and the inevitable battle.

The North’s confidence, which ran so high when the war began, was showing signs of collapse. There seemed to be little enthusiasm for fighting. The governor’s call for an emergency militia of 60,000 men was met with only 16,000 volunteers.

The Federal Army was also running low on its supply of soldiers. The eager recruits who had signed up at the war’s beginning were now approaching the end of their two-year enlistment. By the end of the month, more than 30,000 soldiers were due to leave the army. At the same time, enlistments of new recruits were falling behind goals. Men throughout the North were reluctant to sign up with an army that was so often defeated.

Faced with a drastic shortage, Congress passed the unpopular Enrollment Act, which set up the machinery for drafting 300,000 men. The Post editors disliked the idea of this conscription law, particularly its clause that allowed men to hire substitutes or buy exemptions.

Faces of the American Civil War

Photos courtesy The Library of Congress

A man who received a draft notice could hire another man to take his place in the fighting. If the substitute was found acceptable and duly sworn in, the draftee would be free of any obligation to serve, but only, the Post adds, for “the term for which he was drafted.” After the substitute had served the length of service, the original draftee would be again eligible for conscription.

If the draftee couldn’t find a substitute among poor citizens or struggling immigrants, he could simply buy a personal exemption for $300. (Congress set the amount at a level they felt would be affordable to working-class men. When you adjust that figure for 150 years of inflation, it comes close to $6,000 in 2013 money.)

Before the fighting had ended, the War Department had four separate draft calls, which drew the names of 776,000 American men. Few of these men ever saw military service. More than 20 percent never showed up. Another 60 percent were disqualified for physical or mental disability, or because they were the sole support of a motherless child, a widow, or an indigent parent.

Once sworn into service, recruits and draftees were rushed through basic training before being sent to the front. With only minimal instruction and poor leadership, a Post article claimed, it wasn’t surprising that Union troops had been repeatedly outfought by the Confederates. It quoted a Union army officer who had watched the unskilled Yankees at Chancellorsville:

“They have been taught to load and fire as rapidly as possible, three or four times a minute … they go into the business with all fury, every man vying with his neighbor as to the number of cartridges he can ram into his piece and spit out of it! The smoke arises in a minute or two so you can see nothing or where to aim. The trees in the vicinity suffer sorely, and the clouds a good deal. By-and-by, the guns get heated and won’t go off, and the cartridges begin to give out.

“Meanwhile, the enemy, lying quietly a hundred or two yards in front, crouching on the ground or behind trees … rise and advance upon us with one of their unearthly yells, as they see our fire slackens. Our boys, finding that the enemy has survived such an avalanche of fire we have as we have rolled upon them, conclude that he must be invincible, and, pretty much out of ammunition, retire.

The editors urged the army to abandon the practice of forcing men to load and fire in unison. “Accurate loading, and slow firing, at will, and only when the soldiers has an idea that his ball will tell, will do more execution than hasty loading, and rapid firing at something or nothing.”

It was well-intended advice, but would have been useless during the intense fighting at Gettysburg, where soldiers found themselves loading and firing “as rapidly as possible” simply to hold their ground.

By June 28, Lee learned the Union Army had pursued him across 120 miles in 10 days—a remarkable feat of marching at a time when 5 miles a day was a good speed for an army. He began gathering his forces for a massive blow against the Union army, which he hoped he could deliver at Gettysburg.

He couldn’t have known that a Union general, John F. Reynolds, was also hoping for a fight at Gettysburg because he’d already picked the best ground for his troops.

Next: Americans United to Support the Civil War Troops

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now