After two years of debate, Congress finally passed a new farm bill this week. Concerns about the bill’s $478 billion price tag have long stalled the bill, but the past two weeks have seen rapid progress, and Obama is set to sign the farm bill into law this week.

The farm bill has a long history dating back to the Great Depression and has grown considerably since then. Though it once comprised solely farm aid, other programs such as the food stamp program became part of the bill in the 1970s. Since then, food stamp spending in particular has grown: it now comprises nearly four-fifths of the bill’s total spending.

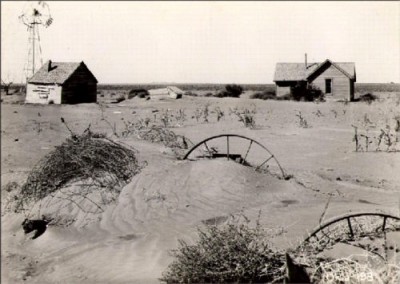

New Deal Origins

Farmers had a rough time in the early 20th century. Crop prices rose dramatically during the 1910s as World War I disrupted European agriculture and drove demand for American crops. In response, many farmers stepped up production with the help of new machines like the combine harvester.

After the war ended, European demand dropped and crop prices plummeted. Many farmers struggled in the 1920s, even as the rest of the economy prospered. Between 1924 and 1928, Congress repeatedly passed legislation to regulate crop prices, but President Coolidge consistently vetoed farm relief.

Things got even worse when the Great Depression hit in 1929. By 1932, crop prices were less than a third of what they had been in 1920.

As part of the New Deal, President Roosevelt sought to help farmers by boosting crop prices. The first farm bill, passed in 1933, launched a program to raise agricultural prices by paying farmers to limit production. In 1938, Congress established the program on a permanent basis, to be renewed every five years.

The 1933 farm bill was just one of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs aimed at helping Americans cope with the Great Depression. Another of these was the first food stamp program, launched in 1939. Agriculture Secretary Henry Wallace, the program’s first administrator, described how it could solve two problems at once:

“We got a picture of a gorge, with farm surpluses on one cliff and under-nourished city folks with outstretched hands on the other. We set out to find a practical way to build a bridge across that chasm.”

Over four years, the food stamp program cost $262 million and helped 20 million Americans. A few years later, under a booming wartime economy, the program no longer seemed necessary. It ended in 1943.

Food Stamps Revived

Nearly 20 years after the end of the first food stamp program, President Kennedy launched a pilot program to test the viability of food stamps. With the 1964 Food Stamp Act, Congress and President Johnson expanded the food stamp program and made it permanent. Though the act included price supports for cotton and wheat, it remained largely separate from the existing farm bill.

The 1977 Food and Agriculture Act was the first to include the entire food stamp program within the farm bill. Since then, food stamps and farm aid have almost always been discussed in tandem.

One of the biggest changes to the farm bill came in 1996, when Congress voted to gradually eliminate farm subsidies over the next seven years. In 1997, however, crop prices slumped, and the next year Congress relaunched agricultural subsidies. This time, instead of paying farmers not to grow, the government offered direct payments to farmers based on how much land they had.

The Current Farm Bill

Congress passed the last farm bill in 2008, which budgeted for $288 billion in relief over five years. The new farm bill would allocate $478 billion over the next five years.

That price tag has been the most contentious point of debate, and the main reason the bill has taken so long, particularly since the Tea Party, which has had a huge influence over House Republicans since 2010, has made spending cuts their top priority.

So why has the farm bill budget grown so much? Food stamps and other nutritional programs comprise nearly 80 percent of its cost, totaling nearly $400 billion of the bill’s five-year spending. From $17 billion annual spending in 2000, food stamps grew to $38 billion in 2008 and $80 billion in 2013, doubling under Bush and then doubling again under Obama.

Economic circumstances are partly to blame. As unemployment rose during the 2009 recession, so did food stamp participation, from 28 million in 2008 to 45 million in 2011. Policy plays a role also. After welfare cuts in the 1990s, President Bush expanded the food stamp program in the 2002 farm bill. The 2009 stimulus also temporarily increased benefits.

The 2014 farm bill cuts $4 billion over five years–approximately 1 percent of current food stamp spending. The biggest way it accomplishes this is by tightening a loophole by which states could make someone applicable for federal aid by giving them just $1 in heating assistance.

Outside of food stamps, the bill cuts $7 billion from direct payments to farmers, but adds funding to crop insurance to compensate. Overall, the new farm bill reduces spending by $8 billion, a small fragment of what remains of a hefty set of programs.

The new farm bill also requires meat to be labeled based on where the animals were born, raised, and slaughtered. It does not include a controversial amendment from Iowa Congressman Steve King, which would have restricted states’ ability to regulate agricultural products.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now