In the December 19, 1914, issue: French refugees return to their village and learn what happened to their homes during the German occupation.

When the Germans Came

By Corra Harris

Journalists in France begged, bargained, and demanded permission to travel toward the war. Some even obtained passes from high-ranking military officers in Paris. But they could travel only a few miles toward the fighting before they were detained at a military checkpoint.

But Post correspondent Corra Harris found a way to bypass the roadblocks. She had heard trains were leaving Paris every day, carrying villagers back to their homes. Early one morning, before sunrise, she joined a large crowd of women at the Gare du Nord train station and climbed aboard a local train for the town of Senlis. No one stopped her, or even asked to see her papers.

The train moved slowly out of the city and ambled across the countryside, never reaching a speed faster than a trotting horse. After two and a half hours it had traveled only 30 miles. But it reached its destination, at last.

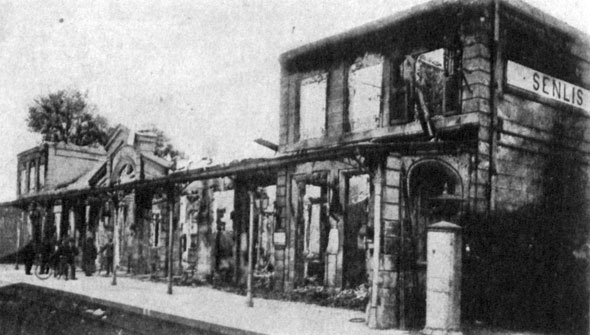

“I should not have known that we were in Senlis if I had not heard the name called, and had not seen women coming down out of the coaches and looking about them with tears streaming down their faces. These were some of the refugees of Senlis who had fled when the Germans came. They were just returning home. They all wore black clothes, and many of them carried homely little things in their hands, which they had snatched at the last moment two months ago. One old woman had a pot with a lily growing in it. Another had a basket with a set of yellow cracked china cups and saucers rattling as she walked.

“That silent crowd of 50 women filed through the ruins of the railway station. The walls of it alone remained. The roof and all the partitions lay a mass of molten metal, stones, and powdered mortar within. On the other side of the station, there were three cabs waiting, but these people were too poor to ride. The cabs went away empty, drawn by horses that looked as if they were merely some of the bones of the general desolation.

“The principal street of the town … was a street no longer, only a long, narrow pile of ruins between the fallen walls of houses as far as sight could reach. The women looked about them. They were confused. They did not know even where they had lived. You cannot recognize your home by blackened walls in the midst of a hundred other walls like them any more than you can recognize a man by his skeleton.

“As we made our way over the stones and rubbish, a woman near me caught sight of a torn lace curtain flapping in and out of a window socket in one of the walls still standing. She gave a cry. She had recognized her home by that scorched rag of tattered lace. Nothing else remained of it now but that and the dead vine still clinging to the casement. The roof was gone, all the inner partitions, all the dear things she had cherished. I left her staring at the ghastly curtain as if she had seen a ghost.”

Not all the villagers had left Senlis. One woman who had remained behind told Harris of how she and her family miraculously escaped being burned to death.

“In the café where I had lunch the little apple-faced waitress was very communicative: ‘When the Germans came we ran down into the cellar. They soaked the house in oil and then set fire to it. And we were in the cellar.’

“‘How many of you?’ I asked.

“‘So many,’ she exclaimed, counting on her fingers. ‘Twenty-eight of them children. We were very still. We could not get out. Suddenly we saw a Prussian’s head thrust through the airhole. He was listening, but we made not a sound. No, the children did not cry. They were so frightened that they went to sleep.’

“‘With the house burning over your heads?’ I exclaimed.

“‘But no; the Blessed Virgin would not let it burn. That oil, it was changed to water.’

“‘How long did you stay there?’

“‘From 2 o’clock in the afternoon until 5 the next morning. It was very hot, and we had no water, no food, but the children did not cry. The next day the Germans came back and set fire to the house again; but we had escaped, so it burned,’ she added simply.

“This girl’s father was a farmer. They lost everything they had. Yet she was not sad. She was sustained by a miracle. The Blessed Virgin had remembered them, the least of these, in the terrible conflagration. So they were safe. No evil could befall them.”

Step into 1914 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post December 19, 1914 issue.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now