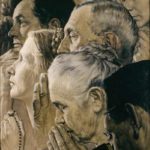

November 24, 1951

© SEPS

Throughout history, most great artists have been storytellers, whether in paintings scratched out on the walls of caves to chronicle the hunt or, later, in lush canvases and intricate frescoes to interpret scenes from the Bible or to record great battles. Norman Rockwell comes from just such a tradition.

Ordinary people doing ordinary things were his subjects for the most part. “The commonplaces of America are to me the richest subjects in art,” Rockwell wrote in 1936. “Boys batting flies on vacant lots; little girls playing jacks on the front steps; old men plodding home at twilight, umbrellas in hand — all of these things arouse feeling in me. Commonplaces never become tiresome. It is we who become tired when we cease to be curious and appreciative.”

The public adored Rockwell from the start, says Laurie Norton Moffatt, director and CEO of the Norman Rockwell Museum. If, in the postwar world of abstract expressionism, folks stared in befuddlement at Ad Reinhardt’s black-on-black canvases or Jackson Pollock’s splatter paintings, Rockwell’s work was a breath of fresh air.

“We know from the fan mail received at The Saturday Evening Post that people were extraordinarily attentive to his work, even to the point of catching him out on details if something was a little off about the picture,” she says. “But most of the letters were accolades of how much they were moved, or touched, by a particular picture.”

Rockwell famously put in long hours, heading off to his studio seven days a week, holidays included. Joseph Csatari, who served for eight years as art director for Rockwell’s Boy Scout paintings, recalls that the artist needed a daily intervention just to pry him away from his easel: “Every day at 11 o’clock, Rockwell’s wife Mary would knock on the studio door to remind him to take a break. ‘If I didn’t,’ she would say, ‘he’d work through dinner.’”

Rockwell’s total production was staggering. In his lifetime, he painted nearly 4,000 images, including 800 magazine covers — 322 for this magazine alone — and ad campaigns for more than 150 companies.

Today his paintings are more popular than ever, commanding eight-figure fees from collectors and drawing crowds to museums. Among his better-known fans are film directors George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Both speak reverently of the artist’s storytelling skills, likening his paintings to film. “He was able to sum up the story and … understand who the people were, what their motives were, everything in one little frame,” Lucas said in an interview. “I think he’s left a legacy that’ll never be forgotten.”

But for all his popularity, and, in fact, because of it, Rockwell was for most of his lifetime a flop in the eyes of the art world. “His success was his failure,” wrote Arthur Danto in a 1986 review in The New York Times, adding, “He possessed a demonic gift for likenesses, but an appalling lack of taste.”

As Moffatt tells it, he was approached by young art students during a visit to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1949 and asked by one, “You’re Norman Rockwell, right?” Touched with pride at being recognized, he was stung by the comment, “My art professor says you stink!”

Rockwell was well aware that he was out of step with the elites of the art world. “I have always wanted everybody to like my work,” he writes in his autobiography. “I could never be satisfied with just the approval of the critics (and boy, I’ve certainly had to be satisfied without it).”

Understanding the criticism Rockwell endured for much of his career requires some perspective about the history of American art, which went through seismic upheavals during his lifetime. Early in the 20th century, classically trained illustrators were national celebrities and trendsetters — admired and emulated the way sports figures and actors are today. “When you look at the 1920s, illustrators like John Held Jr., who was setting flapper fashions, or his forebears Charles Dana Gibson, who created the Gibson Girl, or J.C. Leyendecker, whose ads for Arrow shirts defined the styles and the fashions of the day — these illustrators defined how people dressed and acted, and even shaped what they should aspire to be,” Moffatt says.

But change was coming. Art historians point to the 1913 Armory show in New York as a critical turning point. Today, it’s hard to imagine the uproar the show caused. Nearly 90,000 people came to see the exhibition, which featured then-unknown-in-America artists such as Georges Braque, Mary Cassatt, Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Pablo Picasso, and many others. The abstraction — Cubism! Fauvism! — was a pie in the face of the classical tradition, and many viewers were outraged.

“For the very first time, American artists were introduced to the breaking down of form, of color, anatomy not being presented realistically,” Moffatt says. “American artists realized they had a choice. Many went to Europe to study these new styles, and you began to have this division. Artists could stay in the narrative tradition, painting pictures that are about a recognizable subject — pictures that involve people or landscape — or you could choose to go into these more abstracted forms of art.”

Rockwell, born in 1894, also caught the modern art fever, if briefly. At 29, already an established artist for the Post, he traveled to Paris to study the latest fads. Right from the beginning, it was not a perfect fit, as he writes in his autobiography. But, on his return, he attempted an abstract cover for the Post that was quickly and mercifully rejected. “I don’t know much about this modern art, but I know it’s not your kind of art,” the famously taciturn editor George Horace Lorimer told him. “Your kind is what you’ve been doing all along.”

April 24, 1926

© SEPS

Rockwell did revert to form, of course, but throughout his life, he was occasionally troubled that he was an anomaly among the leading artists of his day. “I think any artist who is a creative genius will go through periods of self-doubt,” Moffatt says. “And what comes through in Norman Rockwell’s own autobiography, where he writes about these episodes of depression, is how he always came through them with a burst of creativity where he was painting his absolute best. It’s a measure of his great strength and of his talent and genius.”

That genius must have been evident immediately to Lorimer, who, 100 years ago, bought two of the unknown young artist’s works at first sight. “Even in those early works, Rockwell was already evidencing the deep sense of observation, that keen sense of just how people interact,” Moffatt says. “If you look at the Boy with Baby Carriage, at first it’s all about the humor — the jeering friends running off to play ball while the older brother is stuck babysitting his sister. But as you look more closely, you’re drawn to the detail: the baby bottle in his breast pocket, the bowler hat clipped onto his lapel. I think it is that attention to detail, the little things that spark the humor, and that always take you a little deeper into the picture, that is the hallmark of his great talent.

“So you have an editor who is very skilled and who knows what he likes, who knows what will work for the Post, and he gave Rockwell a tremendous chance, and of course Rockwell never looked back, and he never let Lorimer down.” (For the full story of Rockwell’s thrilling initial encounter with the Post, see “A Fruitful Relationship,” by granddaughter Abigail Rockwell.)

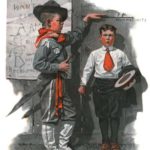

June 16, 1917

© SEPS

There is an additional layer of meaning when you consider the historical backdrop of many of Rockwell’s works. Citing Recruiting Officer, from the June 16, 1917, cover (above), Moffatt notes the obvious storyline — two kids are play-acting as soldiers out in the yard, and one kid isn’t measuring up: “He’s not tall enough to be recruited as a soldier, and the other young man has a wooden sword, and he has this bandana on, and he’s in his scout uniform. What one would have known at that time is that World War I was going on, so Rockwell is incorporating the larger narrative of world events into this narrowly focused microcosm of two kids in the backyard playing. There are so many things to talk about in these pictures beyond the first sort of joke that might stand out to us.”

But, always, the warmth shines through. “It has to be kept in mind that he’s doing all these paintings through the influenza epidemic, through the Great Depression, through the worst wars in the history of the world,” says Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough. “Yet he maintains a positive theme. Rockwell is like the minister who gives an encouraging sermon every week, and keeps the faith in the American ideal.”

McCullough has a unique perspective on Rockwell, having spent a day with the artist when he was still a student at Yale and contemplating becoming an artist himself.

McCullough painted an illustration that was used for the cover of the program of the Yale-Dartmouth football game. “I was a great admirer of Rockwell, and the drawing — a father and son attending a football game — was very much in the Rockwell spirit.”

A classmate of McCullough’s who lived in the Berkshires near Rockwell arranged for the two to meet. “Rockwell could not have been nicer,” McCullough recalls. “I went up to meet him at his studio, above a store on the main street of the town. He was like a character from his paintings — a small, frail, bent-over man, physically not impressive at all, but his spirit was strong. There was no sense that I was in the presence of some great artistic genius. He struck me as a man who didn’t have much time for ego. He was too busy having the best of life through his work.”

McCullough spent the better part of the day with Rockwell. He watched him paint. Then they went to Rockwell’s home and had lunch, and Rockwell was quite encouraging about the young man’s artwork. “It could not have been a more memorable experience. He was one of my heroes,” McCullough says.

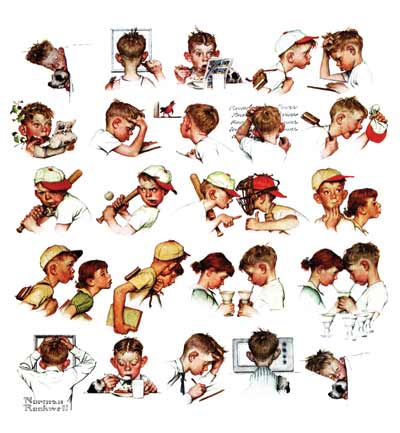

© SEPS

Today, the richness and depth — and yes, the earnest good nature — of Rockwell’s artwork is finally appreciated. (In 2014, Rockwell’s Saying Grace sold for $46 million, setting a record for his work.) But through much of the 20th century, while Rockwell was paid well, the paintings themselves had little or no value — they were merely the medium for delivering his pictures to the printed page. As an example, when the artist donated his canvas of Day in the Life of a Boy to the town’s Community Club for its annual raffle, the work raised a grand total of 50 cents.

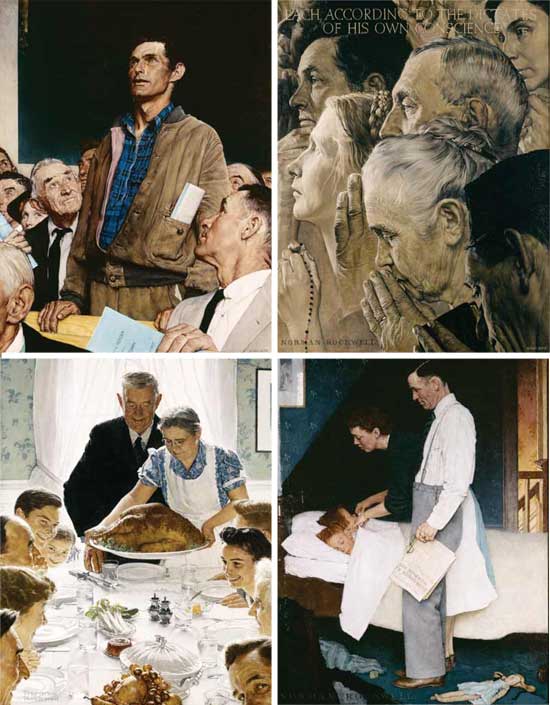

Another anecdote that reflects Rockwell’s modesty about his own canvases comes from Csatari: “On one of my early visits to Stockbridge, I took a walk over to the Old Corner House museum to see some of Norman’s paintings while he took his nap. At the museum, I entered a room that held his Four Freedoms. I remember feeling as if I were in church. But in an instant, the reverence was broken. I saw painters on ladders slapping white latex on the ceiling and spattering the paintings below. I was stunned. I hurried back to the studio to tell Norman, who was back at his easel. He took a thoughtful puff of his pipe, then smiled and said, ‘Gee, Joe, maybe they’ll improve ’em.’”

How did Rockwell’s reputation rebound? As early as 1946, the renowned author of art instruction books Arthur Guptill published Norman Rockwell, Illustrator, a book that celebrated his work, notes Moffatt. But it wasn’t until 1968 that there was any serious interest in his original canvases. Rockwell was caught off guard when New York gallery owner Bernie Danenberg called him one afternoon in July 1968 to suggest mounting a show.

“I’m sorry,” Rockwell said, “but I think you have the wrong artist.”

Danenberg insisted he was not mistaken and drove up to Stockbridge the next day with his gallery manager. Arriving in town, they proceeded directly to his studio. Treasures abounded. Danenberg instantly fell for Lift Up Thine Eyes, a painting that depicted city people rushing past a beautiful old Manhattan church, oblivious to its beauty. The art dealer offered to buy the painting on the spot for $2,500. Rockwell at first refused to accept any money for the painting, saying, “I got paid for it once. I don’t need to be paid again.”

Danenberg persisted, and Rockwell ultimately agreed to sell the painting. He also agreed to schedule an exhibition for October of the same year. As art blogger Ann Restak writes, the exhibition marked the first time that Rockwell sold an original illustration as artwork.

There was a second gallery exhibition in 1972 and another traveling exhibition organized by the Brooklyn Museum. So one could regard the early ’70s as something of a turning point for Rockwell. “He went from being an artist on the cover of magazines to an artist who had his paintings on the walls of museums and galleries,” Moffatt says.

Collectors slowly began to take notice. “We see, around 1978, the very first auctions of Rockwell’s work in the major auction houses, such as Sotheby’s and Christie’s,” Moffatt says. “But it was still rare for American illustrators to be sold at art auctions. Honestly, it wasn’t greatly admired by the auctioneer. It would be shown on the back page of the auction catalogue, and sold for very little.”

It wasn’t until 1999, when the Norman Rockwell Museum and the High Museum of Art produced a large-scale exhibition titled Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, that opinion leaders in the insular art world finally came around. The show traveled to seven American cities, ending in New York at the Guggenheim Museum. Now, writes Restak, his work was finally legitimized “in the hallowed halls of a world-class art institution.”

It didn’t hurt that the exhibition catalogue included essays by such authorities as Moffatt; Ned Rifkin, director of the High Museum of Art; and Thomas Hoving, the former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In his essay for the catalogue, Hoving argues that critics must take another look at Rockwell and “place him in his authentic position in art.” He calls Rockwell “one of the most successful visual mass communicators of the century” and points out that “art history, for snobbish reasons, has always been suspicious of artists considered populizers.”

© SEPS.

Admiration for Rockwell has only grown as his paintings are exhibited with more frequency. “The experience of viewing an original Rockwell is very profound,” Moffatt says.

“The more people see Rockwell’s work in the original format, the more they are just wowed by what an extraordinary artist he was. You just can’t deny the artistry, the exquisite detail, and, of course, his keen observation of human nature.”

“He had a tremendous respect for the virtues of mankind,” Spielberg has said. “And there was a real sense of community, of family, and especially of nation.”

“Above all, Norman Rockwell was an extraordinarily kind person, and he genuinely loved people,” Moffatt says. “There’s so much anger in our nation today — and a certain amount of coarseness in the culture overall. But when people look at Rockwell’s work, not only do they respect it and like it, I think maybe they long for those qualities to be present once again. Not to go back in time, but to bring forward some of these guiding principles of how society could be.”

How will Rockwell be regarded 100 years from now? “Unabashedly I would say we’ll remember him the way we remember Rembrandt and Michelangelo,” Moffatt says. “Rockwell’s work will be held up and admired, and hold its own, alongside the greatest painters in the world.”

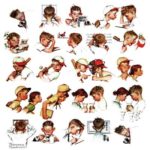

Click images to enlarge:

June 16, 1917

© SEPS

April 24, 1926

© SEPS

August 13, 1927

© SEPS

March 9, 1929

© SEPS

September 26, 1936

© SEPS

September 2, 1939

© SEPS

February 20, 1943

© SEPS

February 27, 1943

© SEPS

March 6, 1943

© SEPS

March 13, 1943

© SEPS

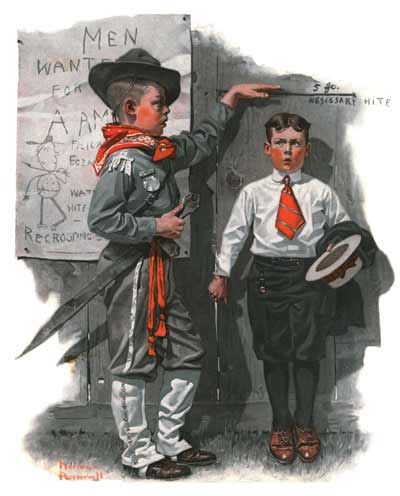

November 24, 1951

© SEPS

May 24, 1952

© SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for the kind comments about the article. The Post will continue to honor Rockwell, of course, as his DNA is still energizing the magazine! (Special thanks to my good friend Anita!)

This is a terrific feature Steve that goes perfectly with Abigail Rockwell’s ‘Fruitful Relationship’ article, each complementing the other.

The art world had no business in dismissing Rockwell’s art and saying such things as mentioned here, at all. They, who marvel over a tiny dot on an otherwise blank canvas, or the emptied contents of a vacuum cleaner bag as art! It’s akin to those who told Einstein he was stupid because he wasn’t a good student, or an acting teacher telling Lucille Ball she’d never make it in show business.

During the 1970’s the POST honored Rockwell many times including special issues in 1976, ’77, a well timed 84th birthday special in 1978, and more in 1979 shortly following his passing. In the decades since, the POST has continued to honor him, both in print and online. The beautiful 100th anniversary issue now joins them in a long, proud tradition of appreciation.

Wonderful article.

Back in college, in the early 1970’s, my art professors were amused by my love of Rockwell. They admitted his skill, but dismissed the art; it was too’narrative’ and easily understood.Plus they thought the world he painted was too optimistic, too focused on the positive aspects of life. ‘Real art’, in their view, should be complex, difficult, and angstful.

Glad to see that over time most such viewpoints have been consigned to the dustbins of bad thinking.

Great article stephen. When I was in grade school my neighbor was on cover of sat. Evening post. He was an adorable overweight kid in a baseball uniform. So cool. Plus I love Stockbridge