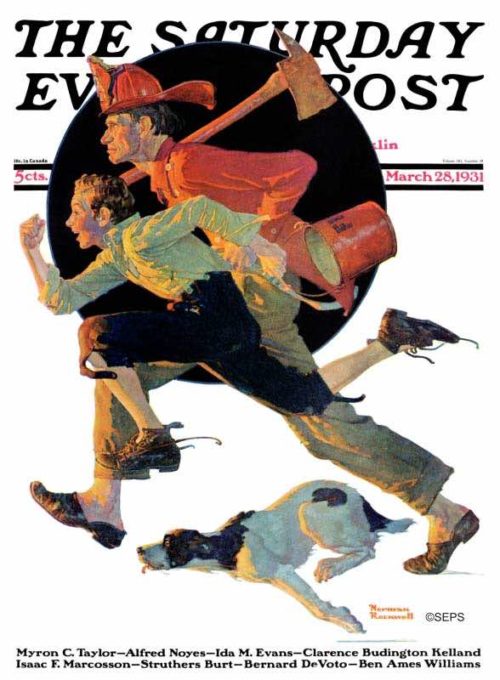

Norman Rockwell

March 28, 1931

A new approach to painting –“dynamic symmetry”- was emerging, and Rockwell’s artist friend told him that he had better begin using it or his work would crumble. His next painting, using this technique, was a disappointment to him. It depicted a stone-faced fireman with an excited lad and his dog rushing to a fire as flames lit the scene. Rockwell gave the painting to a cousin who lived in Philadelphia, and vowed never to wander from the time-tested formulas that had worked so well in the past.

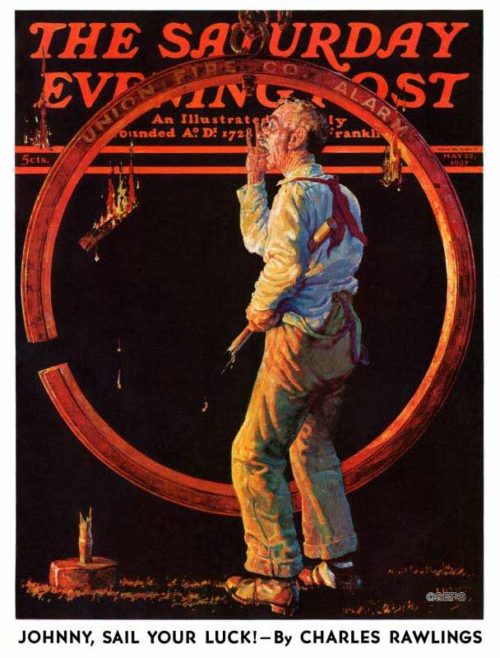

Monte Crews

May 22, 1937

Monte Crews was an illustrator, art teacher, cartoonist, and movie theater owner. Like Norman Rockwell, Crews’ covers are good examples of narrative art, where a single frame tells a detailed story. One can see the sense of urgency in this firefighter’s eyes, as he holds the broken sledge hammer while pieces of burning wood fall around him.

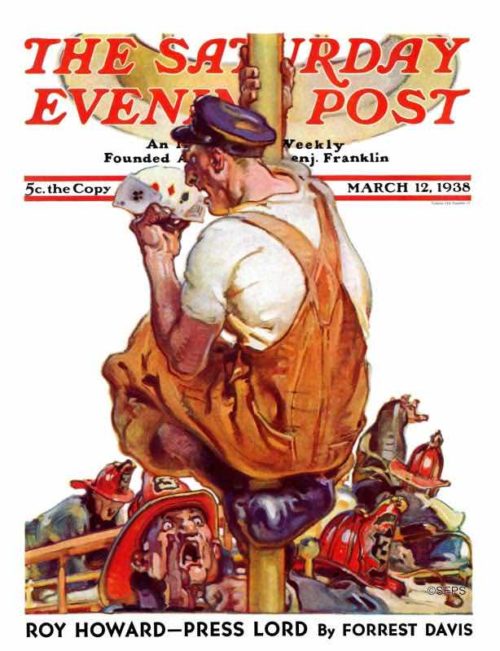

Samul Nelson Abbott

March 12, 1938

Samul Nelson Abbott was known for his intricate and realistic illustrations, and did cover work for many of the major magazines of his day, including The Saturday Evening Post, Woman’s Home Companion, and Ladies’ Home Journal. Abbott painted two covers for the Post.

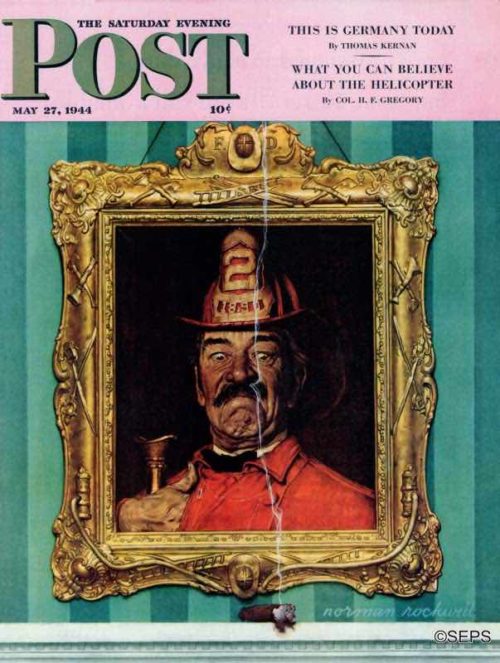

Norman Rockwell

May 27, 1944

One day in the early 1940s, while rummaging through an old junk shop, Rockwell came upon a fancy fireman’s frame. Since it was empty, and he felt he needed to fill it, he painted a cover using the frame and then put a painting into the frame. So actually, the frame generated the picture, and the picture was done for the frame.

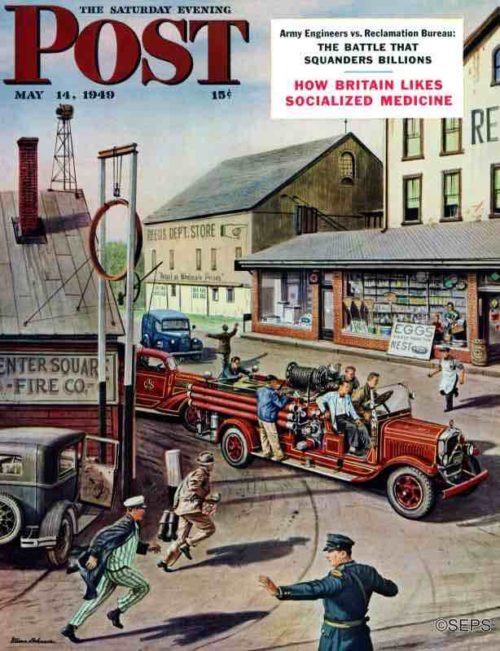

Stevan Dohanos

May 14, 1949

[From the editors of the May 14, 1949 issue] Stevan Dohanos, seeking a small-town fire department with good equipment, but not those elaborate trucks that sprout ladders when a button is pressed, found just the thing at Center Square, Pennsylvania, not far from Art Editor Kenneth Stuart’s home. When the fire boys had done posing. John Henryson, company secretary—who is dashing across the cover in pajamas—made Stuart an honorary, nonrunning member of his outfit. Will this burn up Stuart’s home-town firemen at North Wales and raise his fire-insurance rate? Incidentally, four Post artists, long fascinated by that Center Square department store, have tried to figure out a theme for coverizing it, and failed. Too bad a false alarm wasn’t turned in while they were thinking.

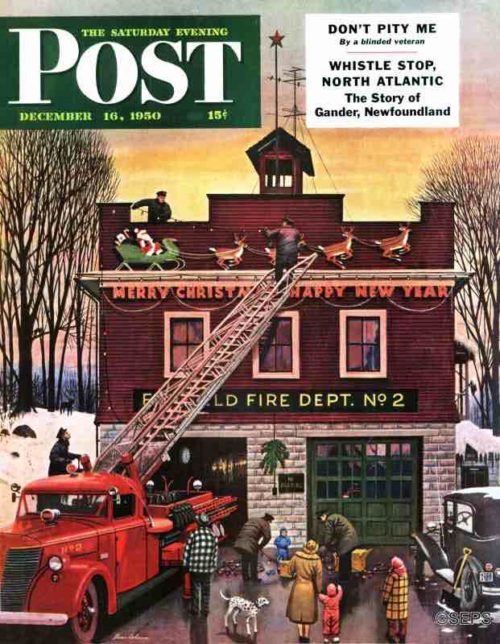

Stevan Dohanos

December 16, 1950

[From the editors of the December 16, 1950 issue] This could be the firemen of the Tunxis Hill Department in Fairfield County, Connecticut, but Stevan Dohanos is symbolizing the merry fact that fire brigades all over America know how to get extension ladders into the Christmas spirit. At this season some fire companies gather broken toys from neighborhood children and repair them for youngsters who otherwise might not find anything in their stockings; and that’s another good thing about firemen. Would it take the cheer out of this scene if the boys hung a big placard behind the brightest lights, saying, “As most of us are volunteers, and hope to stay home Christmas, kindly electrify Christmas trees safely, so that they don’t burn up”? But maybe the sign would catch fire.

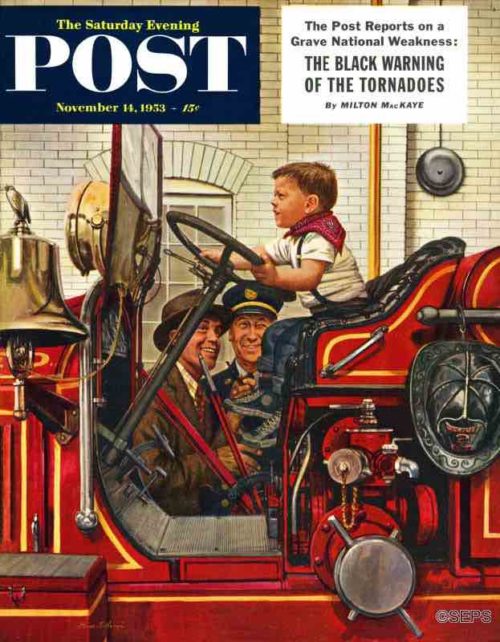

Stevan Dohanos

November 14, 1953

[From the editors of the December 16, 1950 issue] It is comforting to reflect that in spite of rocket ships, disintegrator guns and all the charming new ways of imaginatively risking life and limb, one of the biggest thrills in little lives is still a careering, rip-roaring fire engine. Sort of makes you feel that the future of America is secure. Especially as today’s little imaginers are handicapped by fire wagons no longer being towed by thundering, entrancing fire horses—are you antique enough to remember them? When the lad in the Dohanos scene has had his wonderful moment, papa will say, “Now let me sit there and show you how the pedals work”— for papa wants to play fireman too. Once, when a certain papa did that, the firebell rang, and boy! did he scram down out of there.

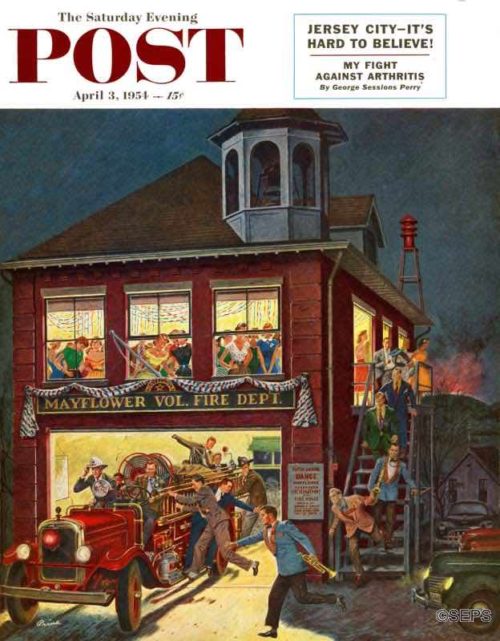

Ben Kimberley Prins

April 3, 1954

[From the editors of the April 3, 1954 issue] What gross inefficiency this is, scheduling the Vol. Fire Dept.’s annual dance the same night as the year’s big fire. The entertainment committee will hear from this, unless they leave town under cover of Ben Prins’ ruddy darkness. One toys with the notion that those flames could be a king-size bonfire organized on the other side of the hill by humorists. More likely the firemen have a grim and dangerous job to do, in which case there will be a special glow of enchantment when the men return safely and again enfold their dear ones in the dance. And then that one fellow now remaining behind with the fire belles won’t turn out to be the beau of the ball. Hey, would he by any chance be the chairman of the entertainment committee?

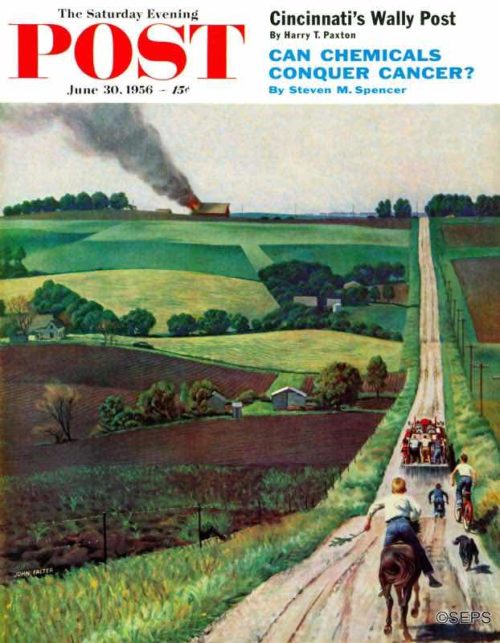

John Falter

June 30, 1956

[From the editors of the June 30, 1956 issue] The scene is out of John Falter’s boyhood, and from this hilltop that looks like an ugly fire. But Falter, having added a modem chemical fire truck which he feels certain will save the barn, reflects that when he starts a fire, he can put it out. Seriously, this evokes a fervent thank-heaven for telephones, gasoline motors, new-fashioned antifire devices, and the know-how and courage of volunteer smoke-eaters. Falter didn’t ride a horse bareback to his long-ago fire; his horse ran away and Johnny dismounted into a passing haystack. Then, finding himself alive, he proceeded on shanks’ mare. To return to 1956, three volunteer boy-models, one on a horse, helped the painter by careering down a steep California hill again and again, which astonished onlookers, as there was no fire.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Hello, Love these “Classics”. Could you please include 2 additional “Firefighter Covers” to the Cover Gallery : Firefighters? They would be “Racing to the Fire”, Jan. 12, 1935 and “Dalmation and Pups”, Jan. 13, 1945. Thanks!