The short explanation is that Fred’s always been a bit on the daft side. That’s what I said to them straightaway, as soon as they began to question me. “I’m his brother,” I said, “and you can take it from me he’s never been overburdened with gray matter.” Those were the exact words I used: “overburdened with gray matter.” Nobody could say Fred was that. But gentle, with all his strength. That’s why the whole thing’s so ridiculous.

I don’t blame them for getting me down there. They have to make inquiries. When all’s said and done, I was there and saw it happen. So did about five thousand other people, of course, but I was the one he kept talking about. “You ask Bert,” he kept saying to them. “Bert’ll tell you I didn’t mean to do it.” That’s what they told me, and I can quite believe it. He always did refer things to me. I did the talking for him, even when we were kids, even though I was 18 months younger. Anything Fred couldn’t quite explain, send for Bert. I had the brains, and he had the brawn. It could have been a good partnership, but as things were it never really worked out. If I’d been a type to get into scrapes, to find myself in a position where I needed a big, strong brother to stand by me, I’d have found it very convenient to have a giant in the family. But then I wasn’t. I got along all right. I soon learned to handle people. All you have to do is watch them — keep your eyes open. And I never got into trouble much, either at school or when I started work. Not real trouble. A bit of boyish high spirits, yes, but to do anything really silly was never in my line.

Come to think of it, my quick wits were no more use to him, really, than his strength and size were to me. I could tell him this and that and the other thing, but I couldn’t stop him being stupid. He was slow, and that was all there was to it. Of course I always did what I could to help him — even after we went different ways, or rather I went ahead and he stayed pretty well where he was. For quite long spells we wouldn’t see much of each other. But when we did meet I’d always ask him how he was getting on, and I was always ready to give him a hand where I could. Ask anybody. Well, that’s how the whole thing came about, isn’t it? Me helping him. That’s what I said to the police. “You try to help somebody,” I said, “and this is where you land up. In the police station being questioned.”

If he’d had just a bit more gray matter, none of this would have happened. He’d have got a decent job and earned a decent wage, and then Doreen wouldn’t have got onto him so much. Another three quid a week would have satisfied her. It’s as simple as that.

Doreen is Fred’s wife. They started going together when he first went to work at Greenall’s. She was there for years, of course, before he started. She was about twenty-nine when he first met her and pretty well in charge of the shop. Old Greenall used to call her his right-hand man. Of course she was very wide-awake. Knew exactly what they had in stock, whether it was on the shelves or in storage, and carried all the prices in her head. Greenall offered to put up her wages when she said she was leaving. If what I heard at the time was anything to go by, he pretty near offered her double. But she just said she’d decided to marry Fred and make a home for him, and she was leaving, and that was that. She told him if he could afford to spend that much on wages he could give Fred a bit more, now that he was going to be a breadwinner. But that wouldn’t wash, of course. Fred was getting seven pounds already, and he wasn’t worth more than that of anybody’s money.

He was slow, you see. Old Greenall used to say he did a lot of work in a lot of time, and it’s true that Fred was never lazy. But he couldn’t hold much in his head; he had to keep coming back for instructions, and he could never see for himself the shortest way to do a thing. Greenall kept him on because he was as strong as three men and as honest as daylight. And it’s true there was a lot of heavy work about the place. There always is, with a grocery. You’d be surprised. Barrels of this and crates of that to be humped about. And loading and unloading the van. Fred used to spend most of his time carrying things about, or doing the deliveries. He hadn’t enough gray matter to do paper work, and when they put him on to serving in the shop he was more of a nuisance than anything else, being so big. The space behind the counter just wasn’t wide enough for him. You might as well try squeezing past an elephant.

It got on Doreen’s nerves from the start. She was fond of him, in her own way, but between you and me I don’t think she’d thought out all the angles before jumping into holy wedlock. She was scared of being left on the shelf — it’s a thought that must come pretty often to a girl who works in a grocery store. She knew what happened when you made a mistake and over-ordered a particular line. You sold what you could and the rest you got rid of cheap, or, in the end, chucked it away. That wasn’t going to be her. Not Doreen. When she saw the magic number thirty coming up on the clock, she jumped. And landed on Fred.

I thought he was rather lucky, at that. She wasn’t a bad looker, and she was smart. But she did get onto him about money. She’d saved a bit, and by putting that to what Fred had they managed to get a house in a decent-enough street. But that was just it. They were out of Fred’s class, really. Most of the husbands were getting twice what he was getting. So their wives had all sorts of things that Doreen couldn’t afford. They managed a telly, but when it came to fridges and cars and stainless-steel sinks, and one woman even had a washing machine! I think it was the washing machine that put the iron in Doreen’s soul. Yes, old Fred wouldn’t be in the mess he’s in today if it hadn’t been for the washing machine.

One Sunday when I was round there she poured out her troubles to me while Fred was out in the garden, the children skipping round him and playing some kind of game. They had two, a boy and a girl. It always seemed to me that he was fonder of them than she was. In a way I don’t blame her. She’d worked part-time until they came, so that they weren’t pinched for money. Then she’d had to give it up. So she had no reason to thank them for being born. Not that she didn’t do her best to bring them up right.

Anyway, that afternoon she stood staring through the window at the three of them. Her face had gone into hard lines, and she looked old and miserable.

“Bert,” she says, jumping straight in without any messing about, “can’t you suggest something?”

“Suggest what kind of something?” I asked.

She looked out at Fred again. He was digging trenches, shoving the spade through the wet soil with his great arms as if it was sawdust. I never saw anybody as strong as he was. The kids were hanging onto him shouting something and laughing. I could hear their voices faintly through the glass.

“What use is he?” said Doreen, following my eyes. “Tell me that. Here am I, with two kids to bring up and everything to pay for, and what does Fred do?”

“He works,” I said. “He earns a living as well as he’s able.”

She looked at me, straight in the eyes. “That’s not well enough. You know it, and I know it. We all know he’s strong, but what’s the good of that?”

I looked at Fred again. He was getting on toward thirty. His body seemed all chest and shoulders. His great barrel of a torso made his legs seem like an ape’s legs. His hair was beginning to get thin in front. As I watched, he laughed at something one of the children said, and his whole face seemed to go into one enormous smile.

“You be satisfied; that’s my advice,” I said to Doreen. “They don’t come any better than old Fred. You’ll never be rich, but you’ve got a good husband, and the kids have got a good father.”

“Keep your advice,” she said, “if that’s the best you can do. Mr. Know-it-all. How would you like to live on seven quid with two children? Scraping for every penny and never having a bit of life. If I want an evening out the only thing I can afford is to go down to the station and watch the trains come in. He’s your brother, and it’s not good enough. Who can I turn to, if not you? You’ve got all the brains; you could easily think of an opening for him. Don’t you tell me to be satisfied,” And more like that. It got so unpleasant I put my coat on and left.

I tried to forget about Doreen and her troubles. After all, I wasn’t her brother; I was Fred’s, and he seemed all right. He was quite happy. She nagged him, of course, but what I say is, if you don’t want to get nagged, don’t get married.

But I couldn’t forget her face. I mean, she was desperate. And I had to admit that seven quid was only seven quid, for a woman who’d been in a good job and never really gone short. Well, she knew Fred wasn’t overburdened with gray matter, I thought to myself. It’s her own fault. But if you feel sorry for somebody, you can’t stop it just by saying it’s their own fault. It nags at you. In fact, it really began to spoil the fun I was getting out of life. I’m in building supply, you know. I had a nice little corner in porcelain stuff just then, everything from insulators to washbasins. I was doing all right, and I’d begun to knock about with a crowd who’d mostly got a fair amount of cash. Chaps who knew their way around. I was on the inside, after always having been on the outside before, and it tasted good. I’d stopped going to the Lord Nelson in the evenings and taken to looking in at the back bar of the George — the private bar. A very nice crowd used to get in there.

Anyway, I mentioned it because Len Weatherhead used to go there very often. He was really one of the big boys. Savile Row suits, a Bentley, the lot. He’d made it up from the ground, and he wasn’t fifty yet. Started as some kind of fairground attendant, then ran a boxing concession, and now one of the biggest all-in wrestling promoters in the country. All-in wrestling! Can’t you see how the whole thing fell smack into my lap?

And yet, funnily enough, I didn’t think of it for a week or two. It wasn’t until one evening when Len Weatherhead came in looking really brassed off. Dead cheesed. The corners of his mouth were right down, and he wasn’t speaking to anybody.

Anyway, I went to work on him. Soon I had him telling me what was wrong. He couldn’t find wrestlers. He’d got the crowds, he’d got the halls, but he couldn’t find the boys to wrestle.

“Only today,” he said. “Two boys I could really rely on. Go anywhere and always put on a good show. Mike the Moose and Billy Crusher — those were their wrestling names. Always put ‘em on together. Well, all of a sudden Ogden — that’s Mike the Moose — comes to me and says he’s dissolving the partnership and going to work somewhere as a gym instructor. Says he knows it’ll mean a drop in the money, but he prefers the type of work he’ll be doing. I ask you! Turning away eighty quid a week!”

“Eighty quid a week?” I said. I saw Doreen running to the shop to buy six washing machines, one for each room.

He nodded. “In the season,” he said. “Of course there’s not a lot doing between April and September. But those two were always up near the head of the billing. And so well-drilled! Knew every wrinkle in the game. Never hurt one another; never had to have any time off with sprains or dislocations or anything like that. And the money I spent on them!”

I began to question him, without letting on that I had anything special in my mind. I learned a lot in a few minutes. All-in wrestling was something I’d never given any thought to. I suppose I just thought it was a matter of a promoter hiring a hall and then a lot of chaps being entered by their managers, like boxers. But of course all-in isn’t a contest; it’s a gymnastic display. The wrestlers have to know each other and work together. Every fight is rehearsed from beginning to end. You’ll notice, if you ever watch a contest, that every time one chap has got the other down and he’s putting some fearful lock on him, twisting his limbs about and making him yell blue murder, and you decide he’s a goner, the one who’s on top suddenly lets him get up. That’s because it’s his turn to be put through the mill next, till the crowd get tired of it and one of them has to win and make room for another pair.

You’ll probably want to ask me what I asked Len Weatherhead. What kind of people watch this? How can they enjoy it when a child of five could see the fights were rigged? Surely it can’t fool them, so what are they doing there? Len Weatherhead couldn’t really answer this, and neither can I. In a way all that happens is that the sight of two big, hefty men beating and gouging hell out of one another excites the crowd so much that they don’t care whether they’re being fooled or not. They’re like middle-aged men watching a striptease. Every one of them knows that the girl isn’t taking her clothes off for him, but never mind; he still wants to see her do it.

Len went on to tell me a bit more. In some cases the wrestlers have what you might call characters. The good guy against the bad guy, like Westerns. One of them will wear some costume that makes him look devilish, and have some frightening name like Chang the Terrible or Doctor Death. He’ll be fighting some blue-eyed, fair-haired type, and he’ll fight dirty to put the crowd against him. They’ll scream all sorts of insults at him, and he’ll snarl and shake his fist, and of course the other chap will let him win right up to the end, and suddenly get the upper hand in the last half minute and damn near break his neck. That’s when they all jump up and down and shout with joy. It works on some of these feebleminded types so much that after a season or two of following it they get to a stage where it’s the only sport they can follow. Oh, yes, somebody had a bright idea there.

“Look here, Len,” I said, choosing a moment when nobody was likely to come breezing over. Of course you know what’s coming. “You’re really short of wrestlers?” I asked him. “I mean, if you found a chap who was willing to go in at the bottom and who was strong — I mean really strong — you’d take him on even if he had no experience?”

He looked a bit crafty at me. “It would depend,” he said. “If he had no experience I’d have to find a partner and train him from the ground up. And he wouldn’t be making me a penny during that time. I couldn’t afford to keep him on more than part-time till he was trained.”

We dickered about it a bit more, and finally he asked me point-blank to come out with whatever was in my mind. So I told him about Fred. A man with the strength of half a dozen wrestlers rolled into one, not making a penny out of it.

Anyway, under his craftiness Len Weatherhead was as keen to do business as 1 was, and before we cleared out at closing time I had a nice little deal all buttoned up for Fred. He was to go down to the gym evenings and weekends and train with this chap Billy Crusher, who’d been left without a partner. As soon as the training had reached a stage where they could work out a fight and get it rehearsed, they could go on, and Fred would move into the big money. if he fought three times a week, he’d clear anything from fifty to eighty quid, depending on the gate money.

Len Weatherhead said he’d have to look Fred over first, but I knew that wouldn’t hold us up. Far from exaggerating his size and strength, I’d even played it down. I didn’t want Len to think of me as a bigmouth. He was a man I could do a lot of business with if I won his confidence. He clapped me on the shoulder before driving off in his Bentley, and I felt on top of the world.

Well, there was no point in messing about, so the very next evening I took Fred out for a drink and started to feed the idea into his mind.

“How are the kids, Fred?” I asked him.

“They’re coming along fine,” he said. “I don’t know which of them’s growing faster. Sometimes I think it’s Peter, other times I think it’s Paula. They just grow and grow. And clever! They get it from their mother. You know what they said the other day?” And he went on to tell me all their clever little sayings. I let him chatter on, because I could see it was softening him up. He was doing all the work for me, and all 1 had to do was listen and buy him a drink now and then.

So I listened until he’d told me everything the kids had done and said since they were one day old, all of which I’d heard before, because he never talked about anything else. And when he’d finished I gave the ball another tap to keep it rolling. Money.

“You’ve got two grand kids,” I said. “Kids who deserve the best. And there are so many opportunities opening up for youngsters these days. That’s where a bit of money comes in handy.”

“That’s what Doreen says,” he said, and worry came over his face. Fred’s expression never changed quickly; it seemed to take time for one to fade and another to take its place. Like sand castles being washed out by the tide. I suppose that was the slowness of his mind.

I knew there was no rushing him, what with the time it took him to get hold of an idea, so I jumped straight in. I asked him if he’d ever heard of Len Weatherhead. He hadn’t. I told him Len Weatherhead made a lot of money for himself and everybody else by promoting all-in wrestling. Fred thought for a bit, and I half expected him to ask me what all-in wrestling was, but finally he turned his head slowly toward me and said, “Yes?”

“Yes,” 1 said. “And, what’s more, Len Weatherhead is very interested in you, Fred. Very interested indeed.”

“Interested in me?” he said, tapping himself on the chest to make quite sure we had our identities sorted out.

“Yes, you,” I said. “He’s heard all about you as a big, strong muscleman. That’s the main thing, you know, in the wrestling game. The rest can be learned. They have a gym where they train you.”

It was as plain as a pikestaff that he simply didn’t know what I was getting at. All-in wrestling and gyms and training just weren’t anything to do with him, and that was that. I felt irritated suddenly. I wanted to drag him along. Cut through that slowness of his.

“Listen, Fred,” I said. “Why do you think I’m bothering to tell you this?”

“Is it a bother?” he said. “I thought we were just having a pint together.”

“Well, so we are,” I said. After all, he was my brother. “But you’re lucky, Fred. You’ve got a smart brother who keeps his eyes open for you.”

“Well, thanks,” he said.

“I can put you in the money,” I said, rushing it along. “No more trouble with Doreen. Everything you want for the kids. Dress them up lovely. Take them on holidays. Send them to a nice school.”

“You can do that?” he asked, looking at me with his eyes wide open. I knew I’d hit the right note.

“Play along with me,” I said, clapping him on the shoulder, “and I’ll see you make eighty quid a week.”

At that he burst out laughing. Or, rather, laughter welled up out of that big chest of his. It took about two minutes to get from his belly as far as his voice.

“All right, laugh,” I said. “But when you’ve finished, let me put you in the picture. Eighty quid sounds a lot to you. It even sounds a lot to me. But it’s just everyday stuff to Len Weatherhead.”

Fred searched in his memory for the name Len Weatherhead, which he’d heard two minutes before, and finally he lifted his head in that perplexed way of his and said, “Wrestling?”

“Wrestling,” I said. “Just the job you were cut out for.”

He picked up his beer, but he only looked at it and then put it down and faced me again.

“You’re joking, Bert,” he said. “It’s one of your jokes.”

“Eighty quid a week,” I said. “Don’t believe me. Don’t listen to me. Go and see Len Weatherhead.”

He shook his head.

“Now look, Fred,” I said. “Do you want to have nice things for Peter and Paula or don’t you?”

“They’re all right,” he said, almost fiercely. “They don’t go short. I take care of them, and we have good times together. They’ve got a house to live in and a garden — ”

“And they could have so much more,” I cut in quickly, “if their father would just realize his own potentialities.”

That last word threw him. It was the sort of word you hear chucked about in the private bar in the George, but not in the Lord Nelson, where we were.

“Don’t mess me about, Bert,” he said. “Don’t mess me about with long words. I do a job, and the wage comes in, and we live on it. We can be happy.”

I didn’t want to get stuck on that point, so I just pushed along. First I drew a picture of Doreen’s sufferings; then I looked forward to the time when the kids would need all sorts of things to help them keep up with the crowd — smart clothes and motor scooters and the rest of it. I told him it wouldn’t always be enough for them to play with him in the garden.

“You’re doing all right,” I said, “now. But when they get bigger you’ll need four, five times the money you’re making now. Who’s going to give it to you? Greenall? That’s a laugh, and you know it.”

I got him so worried that finally he agreed to come and see Len Weatherhead. But first I thought I’d better take him to a wrestling bout to give him an idea of what he was going into. I didn’t want Len Weatherhead to write him off as a total nitwit the first time he met him.

So a couple of nights later we went down to the Town Hall for one of Len’s promotions. It was the usual thing — tickets from about half a crown to a quid, the place pretty well packed out, and everybody excited at the prospect of seeing some licensed mayhem.

Right from the start I knew I was going to have trouble with Fred. I’d taken a lot of trouble to get him into a nice, relaxed mood, so much trouble that I wondered, now and then, why I was doing it. Just brotherly love, was all I could think of. I’d called at his house and picked him up by car — with Doreen’s full approval, of course, because I’d told her what I was doing — and on the way down I’d stopped and got a couple of drinks inside him and even stood him a cigar, one of those one-and-ninepenny panatelas.

But it was no good. Even before the first pair of wrestlers came out I could see that he didn’t like it. There was a kind of edge to the atmosphere that upset him. Of course he was always so gentle; he hated any kind of violence. As we sat there waiting, I looked round and for a moment I saw the scene through his eyes. There was the huge hall, dimly lit, with clouds of cigarette smoke drifting up to the ceiling. And the ring, with that white light beating down on it, like an operating table all ready for someone’s guts to be cut out. And the faces of the people sitting round us weren’t too pleasant. Probably you wouldn’t have minded them on the street, but here they seemed more ugly and cruel, with the sort of thoughts that were going on in their minds.

Then I thought, Eighty quid a week! And I knew I’d talk Fred into it, with Doreen’s help, whatever he thought about this evening.

Well, it started, and I hardly saw anything of the program. I was too busy hanging onto Fred, trying to calm him and make him stay in his seat. If I hadn’t been there I don’t think he’d have stayed beyond the first minute of the first bout.

One fighter was called Eskimo Jim and the other Paddy Doyle, or some such name. Eskimo Jim was the bad one. You could see at once he was going to fight dirty. He didn’t look much like a real Eskimo, but he had thick lips and a flat nose, and his eyes were sort of slanted. The Irish chap was good-looking, of course. All the time the ref was briefing them, or pretending to, the crowd was jeering Eskimo Jim, and he was glaring murder and shaking his fist. Once he broke away and came to the ropes as if he was going to jump over and go for them, but the ref pulled him back, of course. And all the time Paddy stood there looking calm and handsome. I’d have laughed if I hadn’t been so worried about the way Fred was taking it. He didn’t seem to see the funny side at all. The insults and the shouting, and the fist- shaking and threats, were all having a terrible effect on him. It was like trying to lead a horse past something it’s afraid of.

“Relax, Fred, relax,” I kept saying to him. “It’s just entertainment, see? It’s not a fight — it’s an acrobatic performance. Remember that — just an acrobatic performance.”

And just as I said the words, Eskimo Jim pushed the referee to one side and started the fight before Paddy was ready. Of course. He grabbed Paddy’s head and swung it down to knee level, twisting it at the same time so that he damn near dragged it off. Then, while Paddy was reeling about dazed, he gave him a kick in the guts that you could hear all over the building. It was very clever, really, how they managed it. But it was too much for Fred. If we hadn’t been sitting in the middle of a row he’d have been halfway down the aisle, and I’d never have got him back. It was the other customers who saved the situation for me. They’d paid for their seats, the butchery had just begun, and they didn’t want their view blocked by this big elk of a man pushing past them. They hissed at him to sit down, and he did. But he wouldn’t look at the ring.

Well, we stuck it out. Halfway through the evening Fred slumped in his seat as if the will to resist had left him, and he didn’t try to get away anymore. Just sat there staring straight in front of him. I couldn’t even decide whether he was watching the wrestlers or not. As for me, I settled down and watched the show. After all, I’d paid for it. And if Fred wasn’t concentrating, then I’d got to watch hard enough for two. I don’t like to waste my money.

We went across to the pub afterward and I lined up a couple of refreshing pints. Fred threw his down in four swallows. I could see his hand trembling. There was no need to ask him what he thought about all-in wrestling.

“Well, that’s it, Fred,” I said. “I’m not going to try to talk you into anything. I’ve lined up a chance for you, and if you don’t want to take it that’s your affair.”

He turned and looked at me. His face was dead white: I’d never seen it like that before. “You mean you still want me to go in for that?” he asked. I didn’t answer, and he didn’t say anything more. I finished my pint, and then I drove him home. Well, I was thinking to myself, that’s one more thing that’s no good.

Doreen was waiting for us when we got back to the house. I was feeling pretty savage about wasting all that time and money, and when she asked me to come in for a cup of tea. I said no. I didn’t even get out of the car. She called to me from the doorway, and when she saw I wasn’t going to move she came out and spoke to me through the car window.

“What’s wrong?” she asked, in her direct way.

“Oh, nothing,” I said. “Fred doesn’t like all-in wrestling; that’s all. We’ll have to think of some other spare-time hobby for him.”

And I drove off. Let him sort it out, I thought. I could imagine him trying to explain to Doreen that he didn’t want to go in for wrestling even if it did mean eighty quid a week. And, being in a savage mood, I felt it served him right. I’d had a lot of trouble and expense — and, what was worse, I was going to look like a bigmouth when I next talked to Len Weatherhead. Just a stupid, unreliable bigmouth. Let her put him through it, I thought as I locked up the garage.

After that I just assumed it was all over. I kept away from the George for the next few evenings because I wouldn’t have known what to say to Len Weatherhead if I’d met him. I thought I’d let the idea just get lost of its own accord. Anyway, it was a good thing I didn’t rush into any big explanations with Len, because the next thing that happened was something that really surprised me.

I was sitting in the office one morning. I call it the office, though it’s only one room. But that won’t last. I’ve got my eye on a bigger place already, and business is looking up all the time. Anyway, I was sitting there, working out a bit of costing on some washbasins, when the door opened and there was Fred. In the middle of the morning. I ask you.

“What’s up?” I said. “Got the sack?”

“I’m on deliveries,” he said. “I just wanted to have a word with you.”

“What about?” I said. Rather cool. I wasn’t in a mood to let him forget that he’d disappointed me.

“Look,” he said, coming in, but not sitting down. “This Len Who’s-it. When can you take me to him?”

I looked up into his face, and all of a sudden I saw what must have happened. He looked like somebody who’d just come back from Devil’s Island.

“Been talking it over with Doreen, have you?” I asked him, keeping it as casual as I could.

“When can I see this Len?” he asked, ignoring my question. Of course he wouldn’t want to talk about it. Doreen must have really turned it loose on him to drive him to the state where he’d rather go into the ring with Eskimo Jim than face her in his own house.

I reached for the telephone and dialed Len Weatherhead’s office. I wasn’t going to let this cool. Too much depended on it. The luck was with me: I got hold of him straightaway and fixed it for Fred to go and see him and talk business.

After that I relaxed. I knew that Fred wouldn’t change his mind. He might change his mind about wanting to be a wrestler, but he wouldn’t go back on his arrangement to see Len Weatherhead. Which made it Weatherhead’s job to talk him into it. All I had to do was to sit back and collect thanks and smiles.

The next few days passed very smoothly. I bypassed Fred and got the score from Doreen. She welcomed me now as nice as pie. I was the lifesaver who had turned her grocer’s-assistant husband into a big, rich wrestler. At least he was headed that way. Len had evidently taken to him and seen how far his strength would take him in the wrestling business, because he’d given Fred the full treatment. Taken him all round the gym and everything. if Fred still wanted to back out he didn’t get a chance to, because the next thing Len did was to arrange for him to meet Billy Crusher. That’s the fellow who had been in partnership with Mike the Moose, who’d now gone legit as a gym instructor.

I suppose Billy did more than anyone to talk Fred into the game. He had a professional attitude, which was all the more refreshing, because he was going to be with Fred, right there in the ring. He wasn’t asking Fred to do anything he wasn’t going to do himself. That put him straightaway in a different class from me, Doreen, Len Weatherhead and the crowd. I heard so much about Billy Crusher, whose name was really Arthur Trubshaw, that one Sunday morning I looked in, out of curiosity, to watch the pair of them training at Weatherhead’s gym.

They were at it when I arrived, so I stood back and watched them. Arthur was a big, powerful chap, but not so strong as Fred. He was much faster and lighter on his feet, being a trained acrobat and all that, and I could see that he was watching Fred carefully. He wasn’t exactly afraid of him, but he was wary. He didn’t want any mistakes, because he knew that if Fred should forget the script and loose that strength of his in the wrong direction there was every chance of getting hurt. And he wasn’t in the business to get hurt; I could see that. He was a clever performer and knew exactly what he was doing. And his face was unmarked. Nobody had ever taken a swipe at him and broken his nose, and they weren’t going to if he could help it.

When I got there he was showing Fred the way to get out of a lock. The drill was that Arthur got Fred on his back and twisted his legs round in a way that looked bloody agonizing, but (as I heard Arthur keep telling Fred) wouldn’t do him any harm as long as he was expecting it and relaxed. They were to hold this for a bit, while Fred was supposed to writhe about in agony, and then all of a sudden Fred was to kick out so that his feet caught Arthur full in the chest and threw him backward. Then they could go on to the next move. Arthur was pointing out to Fred, very carefully, the exact point on his chest where the feet were to land. No messing about. He didn’t want a kick under the heart to make him groggy, nor did he want the feet to go too high up and get him in the throat. He rehearsed the thing till Fred could have done it in his sleep. Never an inch too high or too low. I was just leaning against the wall, having a smoke and watching the fun, when I heard Len Weatherhead’s voice in my ear. “Seem to be getting to know each other all right,” he said.

“That chap Arthur’ll bring Fred along all right,” I said. “He’s working very hard on him.”

“I should hope he is working hard,” said Len a bit sourly. “He’s on full pay during this training period, and he doesn’t have to fight any bouts. He gets as much for one of these training sessions as he does for a fight in the ring.”

Just as he spoke Fred brought his fist down on the small of Arthur’s back. Arthur must have told him to, but perhaps Fred was an inch or two outside the target area or brought it down too hard or something. Anyway, Arthur collapsed on the floor, gasping that his kidneys were ruptured and that he was going straight round to his lawyer and sue everybody. Fred stood over him, looking apologetic and Len Weatherhead went over.

“Bad luck,” he said, trying to pass it off cheerful. “Fred’ll have to watch what he’s doing — won’t you, Fred?”

“It looks easy from where you’re standing,” said Arthur, fixing Len Weatherhead with a very cold eye. His face was white. “I ought to get double pay for this,” he said.

“Oh, come on, Arthur,” said Len, fencing him off. “You know you do all right.”

“All right, is it?” said Arthur, climbing to his feet. “You come and have a bash at it if it’s all right.”

“What did I do wrong?” Fred puts in, as if he was back at Greenall’s and had put some bags of flour in the wrong place or something.

“I’ll show you what you did wrong,’ said Arthur, and suddenly he seized hold of the back of Fred’s neck, dragged his head down till he was bent double, and then slammed him in the kidneys with his fist. It made me feel faint to see it. As for Fred, he crumpled up. I thought he was going to be sick. Finally he dragged himself onto his hands and knees, but he couldn’t get any further.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” said Arthur. Really cool he was. “Get that into your head, and maybe we’ll start making progress.”

“Fred,” I said through the ropes. “How are you feeling?”

“Don’t overdo it, Arthur,” said Len Weatherhead.

“He’s got to learn,” said Arthur. But he sounded a bit nervous, because Fred was climbing onto his feet now, with sweat breaking out all over him, and none of us liked the look on his face. The gentleness was gone, and it seemed full of nothing but pain and rage. His huge chest made him seem top-heavy, and as he took a step or two toward Arthur he seemed to waddle like a gorilla.

Arthur stood his ground, but he fell automatically into a wrestler’s crouch, ready to defend himself. He sank his head down between his shoulders so that he wouldn’t get his neck broken. Instinct, I suppose. Actually it was all over in seconds. Len and I both broke into action. Len climbed through the ropes and got between them, and at the same time I leaned over and got hold of Fred’s arm.

“Don’t do it, Fred,” I said. “It’s me — Bert.”

He hadn’t realized I was there, and the sound of my voice started him out of his trance. But his mind moved slowly, as usual, so it was like watching a diver come up from the ocean floor.

“He hit me,” Fred said to me, as if we were back on the old asphalt playground.

“That’s enough for today. Out of the ring,” said Len Weatherhead in his manager’s voice.

Arthur came over to Fred and looked him straight in the eye. I had to admire his pluck.

“No offense, Fred,” he said. “I got a bit rattled when you hit me in the wrong place; that’s all. Let’s try that again.”

I liked him for doing it his own way, ignoring Len Weatherhead’s order to break it up for the day. And he was certainly risking something by inviting Fred to give him another punch. But it worked perfectly. They went through three or four movements that looked like dance steps, and then Fred swung his fist down, and this time it must have been placed right, because, although the sound thumped out like somebody kicking a suitcase, Arthur just grinned, and the two of them went off to get dressed.

I saw Len Weatherhead staring after them, looking very excited. “I’ve got a name for him,” he said. “Did you see that look that came over his face? Sort of apelike? That’s worth a fortune in the ring.”

Well, a fortune was a fortune, but Fred was still my brother, so I didn’t exactly gush over this discovery of his. “What’s the name?” I said, a bit short.

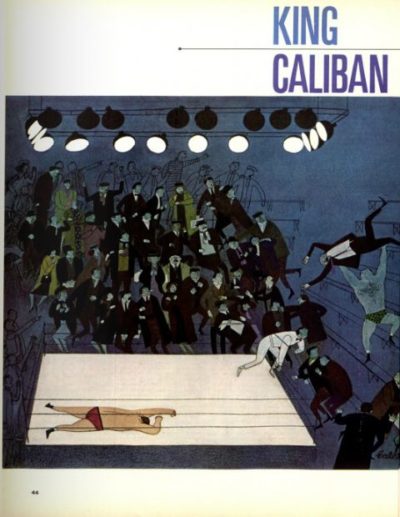

“King Caliban,” he said.

“King who?” I asked.

“Caliban. He was some kind of monster on a desert island. That’s the angle to stress for Fred. The barbaric.”

“Why not call him the Missing Link and have done with it?” I asked. But as soon as I’d spoken I wished I hadn’t. If I wanted to stay in with Len, I had to leave him to run his business his own way. He gave me a look that told me clearly that when he wanted my advice he’d ask me for it. So I decided to button up and make myself scarce. I didn’t want to spoil everything now that it seemed set fair. I mean to say, it’s through playing along with chaps like Len Weatherhead that chaps like me get their place in the sun.

After that I played it cool for a while. I kept my nose out of it and didn’t see anything of Len — or of Fred and Doreen, for that matter. Time jogged along, and I knew it must be time for Fred and Arthur to have a bout in public, but I didn’t think about it much. Then, late one afternoon as I was just locking up the office, Doreen showed up.

“I want you to do me a favor, Bert,” she said, coming to the point, as usual.

“I know,” I said. “Hold Fred’s hand when he goes into the ring.”

“No; be serious,” she said. Her face had gone thin, it seemed to me. Something had frightened her.

“Fred’s acting up strange,” she said. “Since he gave up at Greenall’s and gave all his time to practicing with Arthur.”

“I didn’t know he’d done that,” I said.

“Yes, the last three weeks before their first bout,” she said. “That was the arrangement. Mr. Weatherhead’s been paying him the same wage as he’d have got at Greenall’s. The three weeks’ll be up in four days, Tuesday night. That’ll be his first professional fight, and then he’ll get the same pay as Arthur.”

So she hadn’t touched the big money yet. Just the worry and uncertainty.

“Where do I come in?” I asked her.

“Fred doesn’t like it,” she said. “He’s doing it, but he doesn’t like it. And sometimes he seems so strange. I hardly know him anymore.”

“When he’s earning you eighty quid a week,” I said, “you won’t care whether you know him or not.”

“Bert, that’s not fair,” she said, and all of a sudden if she didn’t burst out crying. Doreen, of all women!

“He frightens me,” she said, sobbing so you could hear her in the street. “The other day we had a bit of a difference. I was for telling the children about his new job, and he said no, let them think he still worked at Greenall’s. ‘But they’re bound to find out, Fred,’ I said. ‘Why not tell them now? Besides, Peter’ll be proud to have a real wrestler for his dad.’ I was going on like that when all of a sudden he gave a sort of roar. I never heard him make a noise like that before. And he glared at me. His eyes seemed like an animal’s, Bert. I thought he was going to murder me.”

“Did he lay a finger on you?” I asked.

“No,” she said.

“Well, then,” I said. “If every man who shouted at his wife could scare her as much as you’re scared, the world’d be a happier place.”

She seemed a bit easier in her mind. After all, there’s nothing like having somebody tell you your fears are just imagination. But she hadn’t finished with me. She pressed on to the next point.

“Promise you’ll come on Tuesday night, Bert,” she said. “I feel I must be there but I can’t stand it by myself.”

“Why don’t you stay at home?” I said.

“Oh, I couldn’t,” she said. “1 must be with him.”

It seemed a funny idea to me. With him. Her and five thousand other people. But I said I’d go. I wasn’t keen, but she was so anxious — and, besides, I was curious to see how the act would go over.

I asked Doreen if she’d got any free tickets, and she said no. That riveted it. I mean it really convinced me that she must be feeling bad about things to miss a chance of saving at least fifteen bob.

Anyway, I called for her on the night. She’d asked me to go round at about six to have a bit of a meal before we set off, and as luck would have it I got there just as Fred was leaving. Len Weatherhead, giving him the VIP treatment because it was his first bout, had called for him in his Bentley, and Arthur was along too. The three of them were just coming out of the house as I got there, and I must say it looked exactly like a man being arrested by two Scotland Yard detectives. They were jollying him along, and Arthur was even carrying the little suitcase which I suppose contained his wrestling outfit. I recognized it. It was his old football case. He used to keep his shorts and boots and things in it, with a little bottle of liniment. That was when we were between about eighteen and twenty-one, both living at home. It made me feel funny to see the old football case going out through the door on such different business. And there was old Fred. He didn’t recognize me. At least, I spoke to him and he looked to me, but he seemed to stare straight through me. His face looked sad and lonely, as if he’d spent about five years in a desert and given up hope of ever meeting another human being.

Well, I thought, the first time is always uphill, whatever it is you’re doing. He’ll settle down. I went on into the house and there was Doreen with the children. She’d got some game out on the table, a jigsaw puzzle or something, and was trying to get them interested in it to cover up for Fred. But she wasn’t having much luck. They could tell there was something going on, and they both kept asking where dad was till it nearly drove her nuts.

We ate some kippers, neither of us saying anything much, and then the neighbor who was going to mind the kids came in, and we got into our coats and on our way. In the car I started trying to raise Doreen’s spirits a bit. “As of tonight,” I said to her, “you and Fred can kiss your worries good-bye. A solid fifty to eighty quid a week in the season, and he can always go back to humping groceries when his reactions begin to slow down and he can’t wrestle any longer. You’re a very lucky girl,” I told her.

“But if it’s going to make Fred different — ” she whined, but I cut her short. I wasn’t having any of that.

“Different, my foot,” I said. “It’s just exchanging one trade for another. This isn’t fighting. It’s an acrobatic display, and Fred’s been well trained for it. It’s the chance of a lifetime. Considering he isn’t overburdened with gray matter, this is the only kind of profitable work he can be trained for.”

She quietened down a bit, but when we got to the Town Hall and saw the crowd streaming in she got all upset again, and to tell the truth I didn’t feel any too good myself. The faces! Like things you’d see in a nightmare. I didn’t know which were the worst, the men or the women. There were women of all ages, from grandmothers down to teen-agers, and they all had that bright-eyed look that people wear when they’re going to see something really horrible. To see a man get hurt — that was what they were there for, and it was as plain as if they’d had it written on sandwich boards. Perhaps they’d all been ill-treated by a man at some time or other. Perhaps every woman has. Well, I thought, at least the all-in wrestling game won’t ever lack support. The cinemas can close, the dog tracks can close, but this’ll keep going. Fred’s onto a good thing. But I wasn’t too happy inside.

The usual flourishing and announcing went on, and then the first bout started. It was between a character covered from head to foot in red tights, with just little holes for his eyes, and another chap who’d gone to the other extreme and was nearly naked. The red one was called the Scarlet Fiend or the Red Devil or something. He was the one the crowd were supposed to be against, though as far as I could see they were both equally horrible, and when it came to fighting dirty, hitting the other chap when he wasn’t looking and the rest of it, there was nothing to choose. But the crowd started to get worked up straightaway. The girls! Screaming advice as to how to hurt one another. And such technical advice too. Where they picked it up I don’t know. But the worst was a big, bald-headed fellow about four seats away from me. We were in the third row from the ringside, and I could see that if they’d been ringside seats this chap would have had his head through the ropes to shout better. He seemed completely beside himself. Nothing short of complete bestiality would satisfy him. He must have been some kind of pervert like you read about in the Sunday paper. He never stopped shouting. And when the action really got hot he’d leap to his feet and start dancing about with excitement till the people behind him had to grab him and pull him down again so they could see.

I saw Doreen glancing at this bald chap once or twice, and 1 could tell what she was thinking. If he shouted like that when Fred was fighting she wasn’t going to be able to stand it. I made a little joke about Baldy, to get her to see him as funny, but I couldn’t put my heart into it. I didn’t think he was funny myself. So I concentrated on the money. “It’s worth it for eighty quid,” I said to Doreen. She gave me an expressionless look and I couldn’t tell what was going on in her mind.

We watched three or four more bouts, and I began to feel numb. My sense of proportion came back, and I thought, Well, it’s just a lot of silly fools shouting and getting worked up. “All in the day’s work,” I said to Doreen. She gave me the same look again.

I got so sunk in my thoughts that I hardly watched the ring any more, and it shook me to hear all of a sudden the name Billy Crusher shouted out by the emcee. He went on to tell the fans that this popular fighter was back after a spell of rest and that he was matched tonight with the most dangerous opponent he had ever faced, an untamed giant straight from the jungle. And there they were climbing into the ring, and the emcee was bawling, “King Caliban!”

Anyone could tell how it was going to be slanted. Arthur had those flashy good looks, especially when you saw him from a few yards away with the arc lights shining down on that smooth torso. The idol of the gallery. Especially the women. Fred would have looked pretty lumpy and plain anyway, and to make it worse they’d dressed him in a leopard skin so that he looked like a jungle chieftain in a “B” picture. I don’t think they’d actually used greasepaint on him, but it’s a fact that his face looked much uglier than I’d ever seen it before. Perhaps it was just the angle at which I was looking up at him, but his forehead seemed narrow and sloping. I don’t think I’d have recognized him if I hadn’t known.

The crowd was well away by now, having witnessed half a dozen crimes of violence already, and they started jeering poor old Fred straightaway, calling him all sorts of names and telling Arthur to throttle him and put a stop to his career. I knew Fred was supposed to feed all this by reacting and making all sorts of threatening gestures, but he just stood there looking lonely. It made him seem subhuman, like a bear that had been brought in to be baited. I glanced at Doreen. She was staring down at her feet. I knew she wouldn’t look at the ring.

The fight started, and they went pretty smoothly into the routine. Arthur’s training had been good, and I was hoping they’d get through without any accidents and finish with it so that I could take Doreen home. Then when she had Fred back with her, plus a big fat pay packet, things would seem rosier. This was the low ebb, having to sit here and watch them twist one another’s limbs.

The bald chap seemed to have taken a real dislike to Fred, hooting insults at him right from the start, rejoicing whenever Arthur looked like maiming him and groaning like a stuck pig when Fred was on top. I nearly leaned over and asked to him to shut up, but it wouldn’t have done any good. He was demented. I think he wanted to attract Fred’s attention, to have him come to the ropes and shake his fist or threaten to come down and do him. That’s what those nut cases want — to be in on the act. “Serve you right!” he’d scream whenever Fred got jumped on or twisted. “That’s what you need!” I could see it was making Doreen sick, and I felt a bit shaky myself.

What was worse, I could see that Baldy was beginning to rattle Fred. His voice must have got in through Fred’s insulation, so to speak. Every time he was taking punishment, to hear that screech right in his ear — it was enough to send him round the bend, if he hadn’t been halfway there already.

At one point, after they’d done a very clever double fall which ended with Fred being thrown up in the air and landing on his back, Baldy set up such a howl of glee that Fred turned on one elbow and looked at him. He could see who was doing the shouting, and he gave Baldy the same look that I’d seen him give Arthur in the gym that morning. His subhuman look. I felt myself break into a sweat. If that was how he’d looked at Doreen, no wonder she was frightened. He slowly got to his feet, still glaring at Baldy, then slowly he turned to face Arthur, who was waiting to get on with the act.

From that moment on, Fred’s performance went to pieces. His timing went off, and he seemed to be acting in a dream. He was so much slower than Arthur that Arthur had to keep waiting for him, and it began to look obvious. I saw Arthur’s lips moving, and knew he was whispering to Fred, trying to get him to snap it up. Then suddenly Fred made a bad mistake. He put the wrong lock on Arthur and really hurt him. Arthur twisted away, and, with the same quick flash of temper I’d seen him show before, he dug his elbow savagely into Fred’s ribs. It was more petulant than anything else — a kind of reminder to keep his mind on the job. But it was too much. Fred must have seen red. He swung round and slapped Arthur across the side of the head with his open hand. It made Arthur reel across the ring. And before anyone could stop them they were fighting. It was the strangest thing I ever saw, the way they switched from mock fighting to real in a couple of seconds. They were both mad and out to hurt each other.

Naturally that didn’t last long. The ref saw what was going on and moved in to break it up. But at that moment Arthur got a punch in that went under Fred’s ribs and made him gasp for breath. He stood there for a second, fighting for breath, and at that moment I saw his face. It was quite calm. Just very lonely. As if he’d gone beyond anyone’s power to help him or speak to him.

It was all over in a moment. Fred pushed the ref away, turned to Arthur and suddenly swung his fist in the air, like a club, and crashed it down on Arthur’s skull. The whole place fell silent. Everybody knew this was not fooling. Arthur lurched, tried to put his hands up to his head, then fell forward. I remember thinking, He’s killed him. I still don’t know, for that matter. He’s still unconscious, but he may get better.

I said the whole place fell silent. But there was one still on his feet and shouting. Yes. The bald chap. He was pointing a finger straight at Fred and screaming, “Dirty! A foul! He fouled him!” Nobody else was moving or making a sound, but Baldy couldn’t stop yelling.

Then like a nightmare I saw Fred come across the ring and through the ropes. I tried to call to him, but my throat was dry, and nothing came out. I knew what he was going to do. The people in the front row scattered as he walked straight over them. And the second row. The ref jumped down and scrambled after him. Doreen was screaming. But it was too late. Fred had got hold of the bald chap and was lifting him above his head like a log of wood. Higher and higher he lifted him. My voice came back and I cried, “Don’t do it, Fred! Don’t do it!”

But he did it. He flung the man down across the wooden seats, as if it was the seats he hated and he was just using the man’s body to break them with.

Don’t ask me how we got out of there. Of course the police were in there within five minutes. They got Fred into a Black Maria even before they got the bald chap into an ambulance. As far as I can make out, he’ll live. So it all might have been worse. Of course I feel a bit shaken. I spent the night on the settee at Doreen’s after the police let me go. But I didn’t sleep. And I haven’t felt up to doing anything all day. As I said to them, that’s what happens when you try to help anybody. Well, it’s a lesson to me.

Doreen’s telephoned to say that Fred’s been asking for me. Well, let him ask. He got himself into this; let him get himself out. I mean to say, all right, it was my idea for him to go in for the wrestling. But how was I to know he’d do a bloody silly thing like that?

And what will I say to Len Weatherhead when I meet him?

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now