“Richard, Richard,” they said to me often in my childhood, “when will you begin to see things as they are?”

But I always learned from one thing what another was, and it was that way when we all went from Dorchester to New York to see my grandfather off for Europe, the year before the First World War broke out.

He was a German — my mother’s father — and it was his habit, all during the long time he lived in Dorchester, New York, to return to Germany for a visit every year or two. I was fearful of him, for he was large, splendidly formal in his dress and majestic in his manner, and yet I loved him for he made me know that he believed me someone worthwhile. I was ten years old, and I could imagine being like him myself someday, with glossy white hair swept back from a broad, pale brow, and white eyebrows above China-blue eyes, and rosy cheeks, a fine sweeping moustache and a well-trimmed white beard that came to a point. He sometimes wore eyeglasses with thin gold rims, and I used to put them on and take them off in secret. I suppose I had no real idea of what he was like.

There was something in the air about going to New York to see him off that troubled me. I did not want to go.

“Why not, my darling?” my mother asked as I was going to bed the night before we were to leave home. Before going down to dinner, she always came in to see me, to kiss me good night, to glance about my room with her air of giving charm to all that she saw, and to whisper a prayer with me that God would keep us.

“I don’t want to leave Anna.”

“What a silly boy. Anna will be here when we get back, doing the laundry in the basement or making Apfelkuchen, just as she always does. And while we are gone, she will have a little vacation. Won’t that be nice for her? You must not be selfish.”

“I don’t want to leave Mr. Schmitt and Ted.” Mr. Schmitt was the iceman, and Ted was his horse.

My mother made a little breath of comic exasperation, looking upward for a second. “You really are killing,” she said in the racy slang of the time. “Why should you mind leaving them for a few days? What is so precious about Mr. Schmitt and Ted? They only come down our street twice a week.”

“They’re friends of mine.”

“Ah. Then I understand. We all hate to leave our friends. Well, my darling, they will be here when we get back. Don’t you want to see Grosspa take the great ship? You can even go on board to say good-bye. You have no idea how huge those ships are, and how fine.”

“Why can’t I go the next time he sails for Germany?”

At this my mother’s eyes began to shine with a new light, and I thought she might be about to cry, but she was also smiling. She gave me a hug. “This time we must all go, Richard. If we love him, we must go. Now people are coming for dinner, and your father is waiting downstairs. Now sleep. You will love the train, as you always do. And in New York you can buy a little present for each one of your friends.”

It was a lustrous thought to leave with me as she went, making a silky rustle with her long dress. I lay awake thinking of each of my friends, planning my gifts.

Anna, our servant, was a large, gray, Bohemian woman who came to us four days a week. I spent much time in the kitchen or the basement laundry listening to her rambling stories of life on the “East Side” of town. She had a coarse face with deep pockmarks. I asked her about them one day, and she replied with the dread word, “Smallpox.”

“They thought I was going to die,” she said. “They thought I was dead.”

“What is it like to be dead, Anna?”

“Oh, dear saints, who can tell that who is alive?”

It was all I could find out, but the question was often with me. Sometimes in the afternoon, when I was supposed to be taking my nap, I would hear Anna singing, way below in the laundry, and her voice was like something hooting up the chimney. What should I buy for Anna in New York?

And for Mr. Schmitt, the iceman. He was a heavy-waisted German-American with a face wider at the bottom than at the top, and when he walked he had to swing his huge belly from side to side to make room for his steps. He had a big, hard voice, and we could hear him coming blocks away, calling, “Ice!” in a long cry. Other icemen used a bell, but not Mr. Schmitt. I waited for him to come, and we would talk while he stabbed at the great cakes of ice in his hooded wagon, chipping off the pieces we always took — two chunks of fifty pounds each. His skill with the tongs was magnificent, and he would swing a chunk up on his shoulder, over which he wore a sort of rubber chasuble, and move with heavy grace up the walk along the side of our house to the kitchen porch.

“Do you want to ride today?” he would ask, meaning that I was welcome to ride to the end of the block on the high seat above Ted’s rump, where the shiny, rubbed reins lay in a loose knot, because Ted needed no guidance and could be trusted to stop at all the right houses and start up again whenever he felt Mr. Schmitt’s heavy, vaulting rise to the seat. I often rode to the end of the block, and Ted, in the moments when he was still, would look around at me, first from one side, and then the other, and stamp a leg, and shudder his harness against flies, and in general treat me as a member of the ice company, for which I was grateful

What could I buy for Ted? Perhaps in New York they had horse stores. My father would give me what money I would need, when I told him what I wanted to buy. I resolved to ask him, provided I could stay awake until the dinner party was over, and my father, as he always did, would come in to see if all was well. How much love there was all about me, and how greedy I was for even more of it.

The next day we assembled at the station to take the train. It was a heavy, gray, cold day, and everybody wore fur except me and my Great-aunt Barbara Tante Bep. She was going to Germany with my grandfather, her brother.

This was an amazing thing in itself, for, first of all, he usually went everywhere alone, and second, Tante Bep was so different from her magnificent brother that she was generally kept out of sight. She lived across town on the East Side in a convent of German nuns, who received money for her board and room from Grosspa. She resembled an ornamental cork that my grandfather often used to stopper a wine bottle. Carved out of soft wood and painted in bright colors, the cap of the cork represented a Bavarian peasant woman with a blue shawl over painted gray hair. The eyes were tiny dots of bright blue lost in wooden crinkles, and the nose was a long wooden lump hanging over a toothless mouth sunk deep in a poor smile.

Now, wearing her jet-spangled black bonnet with chin ribbons, and her black shawl and heavy skirts that smelled like dog hair, she was returning to Germany with her brother. I did not know why.

But her going was part of the strangeness I felt in all the circumstances of our journey. On the train my grandfather retired at once to a drawing room at the end of our car. My mother went with him. Tante Bep and I sat in swivel chairs in the open part of the parlor car, and my father came and went between us and the private room up ahead.

In the afternoon I fell asleep after the splendors of lunch in the dining car. Grosspa’s lunch went into his room on a tray, and my mother shared it with him. I hardly saw her all day, but when we drew into New York, she came to wake me. “Now, Richard, all the lovely exciting things begin! Tonight the hotel, tomorrow the ship! Come, let me wash your face and comb your hair.”

“And the shopping?” I said.

“Shopping?”

“For my presents.”

“What presents?”

“Mother, Mother, you’ve forgotten.”

“I’m afraid I have, but we’ll speak of it later.”

It was true that people did forget at times, and I knew how they tried then to make unimportant what they should have remembered. Would this happen to me, and my plans for Anna, and Mr. Schmitt, and Ted? My concern was great — but, as my mother had said, there were excitements waiting, and even I forgot, for a while, what it had seemed treachery in her to forget.

We drove from the station in two limousine taxis, like high glass cages on small wheels. My father rode with me and Tante Bep. It was snowing lightly, and the street lamps were rubbed out of shape by the snow, as if I had painted them with water colors. We went to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Fifth Avenue, and soon after I had been put into the room I was to share with Tante Bep, my father came in to make an announcement. He lifted me up so that my face was level with his. His beautifully brushed hair shone under the chandelier, and his voice sounded the way his smile looked.

“Well,” he said, “we’re going to have a dinner party downstairs in the main dining room.”

I did not know what a main dining room was, but it sounded superb, and I knew enough of dinner parties to know that they always occurred after my nightly banishment to bed.

“It won’t be like at home, will it?” I said. “It will be too far away for me to listen.”

“Listen? You’re coming with us. And do you know why you’re coming with us?”

“Why?”

“Grosspa specially wants you there.”

“Ach Gott,” Tante Bep said in the shadows, and my father gave her a frowning look.

We went downstairs together a few minutes later. I was dazed by the grand rooms of the hotel, the thick textures and velvety lights, the distances of golden air, and most of all by the sound of music coming sweetly and sharply from some hidden place. In a corner of the famous main dining room was a round table sparkling with silver, glass, ice, china and flowers, and in a high-backed armchair sat my grandfather. He leaned forward to greet us, and seated us about him. My mother was at his right, in one of her prettiest gowns. I was on his left.

“Hup-hup!” my grandfather said, clapping his hands to summon waiters. “Tonight nothing but a happy family party, and Richard shall drink wine with us, for I want him to remember that his first glass of wine was handed to him by his alter Miinchner Freund, der Grossvater.”

At this, Tante Bep began to make a wet sound, but a look from my father quelled it, and my mother, blinking both eyes rapidly, put her hand on her father’s and leaned over and kissed his cheek.

“Listen to the music,” Grosspa commanded, “and be quiet, if every word I say is to be a signal for emotion!”

Everybody straightened up and looked consciously pleasant. For me, it was no effort. The music came from within a bower of gold lattice screens and potted palms — two violins, a cello and a harp. I could see the players now, for they were in the corner just across from us. The leading violinist was alive with his music, bending to it, marking the beat with his glossy head, on which his sparse black hair was combed flat. The dining room was full of people, and their talk made a thick hum; to rise over this the orchestra had to work with extra effort.

The rosy lampshades on the tables, the silver vases full of flowers, the slow sparkling movements of the ladies and gentlemen at the tables, and the swallowlike dartings of the waiters transported me. I felt a lump of excitement in my throat. My eyes kept returning to the orchestra leader, who conducted with jerks of his nearly bald head, for what he played and what he did seemed to emphasize the astonishing fact that I was at a dinner party in public.

“What are they playing?” I asked. “What is that music?”

“It is called II Bacio,” Grosspa said.

“What does that mean?”

“It means ‘The Kiss.”‘

What an odd name for a piece of music, I thought. All through dinner — which did not last as long as it might have — I inquired about pieces played by the orchestra, and in addition to the Arditi waltz, I remember one called Simple Aveu, and the Boccherini Minuet. The violins had a sweetish, mosquitolike sound, and the harp was breathless, and the cello mooed like a distant cow, and it was all entrancing. Watching the orchestra, I ate absently, chewing hardly at all, until my father, time and again, turned me back to my plate. And then a waiter came with a silver tub on legs, which he put at my grandfather’s left, and took the wine bottle from its nest of sparkling ice and showed it to him. The label was approved, and a sip was poured for my grandfather to taste. He held it to the light and twirled his glass slowly; he sniffed it, and then he tasted it.

“Yes,” he declared, “it will do.”

My mother watched this ritual, and over her lovely heart-shaped face, with its rolled crown of silky hair, I saw memories pass like shadows, as if she were thinking of all the times she had watched this business of ordering and serving wine. She blinked her eyes again and, opening a little jeweled lorgnon she wore on a fine chain, bent forward to read the menu that stood in a little silver frame beside her plate. But I could see that she was not reading, and I wondered what was the matter with everybody.

“For my grandson,” Grosspa said, taking a wineglass and filling it half with water, and then to the top with wine. The yellow wine turned even paler in my glass, but there was too much ceremony for me not to be impressed. When he raised his glass, I raised mine, and while the others watched, we drank together. And then he recited a proverb in German which meant something like:

When comrades drink red wine or white,

They stand as one for what is right,

and a flourish of intimate applause went around the table in acknowledgment of this stage of my growing up.

I was suddenly embarrassed, for the music had stopped, and I thought all the other diners were looking at me; many were, in fact, smiling at a boy of 10, ruddy with excitement and confusion, drinking a solemn pledge of some sort with an old gentleman with a pink face and very white hair and whiskers.

Mercifully, the music began again, and we were released from our pose. My grandfather drew his great gold watch from his vest pocket and unhooked from a vest button the fob that held the heavy gold chain in place. Repeating an old game we had played when I was a baby, he held the watch toward my lips, and I knew what was expected of me. I blew upon it, and — though long ago I had penetrated the secret of the magic — the gold lid of the watch flew open. My grandfather laughed softly in a deep, wheezing breath, and then shut the watch.

“Do children ever know that what we do to please them pleases us more than it does them?” he said.

“Ach Gott,” whispered Tante Bep, but nobody reproved her.

“Richard, I give you this watch and chain to keep all your life, and by it you will remember me,” my grandfather said.

“Oh, no!” exclaimed my mother.

He looked gravely at her and said, “Yes. Now, rather than later,” and put the heavy, wonderful golden objects in my hand. I regarded them in stunned silence. Mine! I could hear the wiry ticking of the watch, and I knew that now and forever I myself could make the gold lid fly open.

“Well, Richard, what do you say?” my father urged gently.

“Yes, thank you, Grosspa, thank you.”

I half rose from my chair and put my arm around his great head and kissed his cheek. Up close, I could see tiny blue and scarlet veins under his skin.

“That will do, my boy,” he said. Then he took the watch from me and handed it to my father. “I hand it to your father to keep for you until you are 21. But remember that it is yours and you must ask to see it anytime you wish.”

My disappointment was huge, but even I knew how sensible it was for the treasure to be held for me instead of given into my care.

“Any time you wish. You wish. Any time,” repeated my grandfather, but in a changed voice, a hollow, windy sound that was terrible to hear. He was gripping the arms of his chair and now he shut his eyes behind his gold-framed lenses, and sweat broke out on his forehead. “Any time,” he tried to say through his suffering, to preserve a social air. But, seized by pain too merciless to hide, he lost his pretenses and staggered to his feet. Quickly my mother and father helped him from the table, while other diners stared with neither curiosity nor pity. I thought the musicians played harder all of a sudden to distract people from the sight of an old man in trouble being led out of the main dining room of the Waldorf-Astoria.

“What is the matter?” I asked Tante Bep, who had been ordered, with a glance, to remain behind with me.

“Grosspa is not feeling well.”

“Should we go with him?”

“But your ice cream.”

“Yes, the ice cream.”

So we waited for the ice cream, and in a moment or two the flow and rustle of rosy-shaded life was once again in the room.

My parents did not return from upstairs, though we waited. Finally, hot with wine and excitement, I was led by Tante Bep to the elevator and to my room and put to bed. Nobody came to see me, or if anyone did, I did not know it.

More snow fell during the night. When I woke up and ran to my window, the world was covered and the air was thick with snow still falling. Word came to dress quickly, for we were going to the ship. Suddenly I was consumed with eagerness to see the great ship that would cross the ocean.

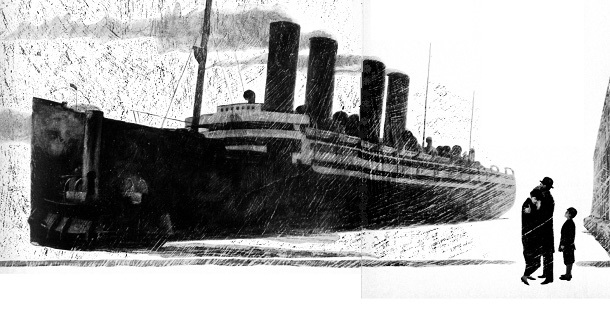

Again we went in two taxicabs, I with my father. The others had gone ahead of us. My father pulled me near him to look out the window of the cab at the falling snow. We went through narrow, dark streets to the piers on the west side of Manhattan, where we boarded the ferryboat that would take us to Hoboken.

“We are going to the docks of the North German Lloyd,” my father said.

“What is that?”

“The steamship company where Grosspa’s ship is docked. The Kronprinzessin Cecilie.”

“Can I go inside her?”

“Certainly. Grosspa wants to see you in his cabin.”

“Is he there now?”

“Probably. The doctor wanted him to go right to bed.”

“Is he sick?”

“Yes.”

“Did he eat something — ” (It was a family explanation often used to account for my various illnesses at their onset.)

“Not exactly. It is something else.”

“Will he get well soon?”

“We hope so.”

He looked out the window as he said this, instead of at me, and I thought, He does not sound like my father. But we had reached the New Jersey side now, and the cab was moving past the docks. Above the gray, snowy sheds I saw the funnels and masts of ocean liners. The streets were furious with noise, horses, cars, porters running, and suddenly a white tower of steam rose from the front of one of the funnels, to be followed in a second by a deep, roaring hoot.

“There she is,” my father said. “That’s her first signal for departure.”

It was our ship. I could see her masts with their pennons being pulled about by the blowing snow, and her four tall ocher funnels.

We went from the taxi into the freezing air of the long pier. All I could see of the Kronprinzessin Cecilie were glimpses, through the pier shed, of white cabins, rows of portholes, and an occasional door of polished mahogany. A confused, hollow roar filled the long shed. We went up a canvas-covered gangway and then we were on board. There was an elegant creaking from the shining woodwork. I felt that ships must be built for boys, because the ceilings were so low and made me feel so tall.

My father held my hand to keep me by him on the thronged decks, and then we entered a narrow corridor that seemed to have no end. The walls were of dark, shining wood, and there were weak yellow lights overhead. The floor sloped down and then up again, telling of the ship’s construction. Cabin doors were open on either side. There was a curious odor in the air, something like the smell of soda crackers dipped in milk, and faraway — or was it right here, all about us in the ship — there was a soft throbbing sound. It seemed impossible that anything so immense as this ship would presently detach itself from the land.

“Here we are,” my father said, at a half-open cabin door.

We entered my grandfather’s room, which was not like a room in a house, for none of its lines squared with the others but met only to reflect the curvature of the ship. Across the room, under two portholes whose silk curtains were drawn, my grandfather lay in a narrow brass bed. He lay at a slight slope, with his arms outside the covers, and he wore a white nightgown. I had never before seen him in anything but his formal day and evening clothes. He looked white — there was hardly a difference of color between his beard and his cheeks and his brow. He did not turn his head, only his eyes. He seemed suddenly dreadfully small, and fearfully cautious, where be- fore he had gone his way magnificently, ignoring whatever threatened him with inconvenience, rudeness or disadvantage. My mother stood by his side, and Tante Bep was at the foot of the bed, wearing her black shawl and peasant skirts.

“Yes, come, Richard,” Grosspa said in a faint, wheezy voice, looking for me without turning his head.

I went to his side, and he moved his hand an inch or two toward me — not enough to risk such a pain as had thrown him down the night before, but enough to call for a response. I gave him my hand and he tightened his fingers over mine.

“Will you come to see me?” he said.

“Where?” I asked in a loud, clear voice. My parents looked at each other, as if to inquire how in the world the chasms which divide age from youth, and pain from health, and sorrow from innocence could ever be bridged.

“In Germany,” he whispered. He shut his eyes and held my hand, and I had a vision of Germany which may have been sweetly near his own; for what I saw were the pieces of brilliantly colored cardboard scenery that belonged to the toy theater he had once brought me from Germany.

“Yes, Grosspa,” I replied, “in Germany.”

“Yes,” he whispered, opening his eyes and making the sign of the Cross on my hand with his thumb. Then he looked at my mother, who understood at once.

“You go now with Daddy,” she said, “and wait for me on deck. We must leave the ship soon. Schnell, now, skip!”

My father took me along the corridor and down the grand stairway. The ship’s orchestra was playing somewhere — it sounded like the Waldorf. We went out to the deck just as the ship’s whistle let go again, and now it shook me gloriously and terribly. I covered my ears, but still I was held by that immense, deep voice. For a moment, when it stopped, the ordinary sounds around us did not come close. It was still snowing — heavy, slow, thick flakes, each like several flakes stuck together.

A cabin boy came along beating a brass cymbal, calling out for all visitors to leave the ship.

I began to fear that my mother might be taken away to sea after my father and I were forced ashore. I saw her at last. She came toward us with a rapid, light step and, saying nothing, turned us to the gangway, and we went down. She was wearing a little spotted veil, and with one hand she lifted it and put her handkerchief to her mouth. She was weeping and I was abashed by her grief.

We hurried to the dock street, and there we lingered to watch the Kronprinzessin Cecilie sail.

We did not talk. It was bitter cold. Wind came strongly from the West, and then, after a third great whistle-blast the ship slowly began to change — she moved like water itself as she left the dock, guided by three tugboats that made heavy black smoke in the thick air. At last I could see all of the ship at one time.

I was amazed how tall and narrow she was. Her four funnels rose like a city’s chimneys against the blowy sky. Stern first, she moved out into the river. I squinted at her with my head on one side and knew exactly how I would make a small model of her when I got home. In midstream she turned slowly to head toward the Lower Bay. She looked gaunt and proud and top-heavy as she ceased backing and turning and began to steam down the river and away.

“Oh, Dan!” my mother cried in a broken sob, and put her face against my father’s shoulder. He folded his arm around her. Their faces were white. Just then a break in the sky across the river lightened the snowy day, and I stared in wonder at the change. My father, watching after the liner, said to my mother: “Like some wounded old lion crawling home to die.”

“Oh, Dan,” she sobbed, “don’t, don’t!” I could not imagine what they were talking about. I tugged at my mother’s arm and said with excitement, pointing to the thick flakes everywhere about us, and against the light beyond, “Look, look, the snowflakes are all black!”

My mother suddenly could bear no more. She leaned down and shook me, and her voice was strong with anger: “Richard, why do you say black! What nonsense. Stop it. Snowflakes are white, Richard. White! White! When will you ever see things as they are! Oh!”

“Come, everybody,” my father said. “I have the taxi waiting.”

“But they are black!” I cried.

“Quiet!” my father commanded.

We were to return to Dorchester on the night train. All day I was too proud to mention what I alone seemed to remember, but after my nap, during which I refused to sleep, my mother came to me.

“You think I have forgotten,” she said. “Well, I remember. We will go and arrange for your presents.”

My world was full of joy again. The first two presents were easy to find — there was a little shop full of novelties a block from the hotel, and there I bought for Anna a folding package of views of New York and for Mr. Schmitt a cast-iron savings bank, made in the shape of the Statue of Liberty, to receive dimes. It was harder to think of something Ted would like. My mother let me consider many possibilities among the variety available in the novelty shop, but the one thing I wanted for Ted I did not see. Finally I asked the shopkeeper: “Do you have any straw hats for horses?”

“What?”

“Straw hats for horses, with holes for their ears to come through. They wear them in summer.”

“Oh. I know what you mean. No, we don’t.”

My mother took charge. “Then, Richard, I don’t think this gentleman has what we need for Ted. Let’s go back to the hotel. I think we will find it there.”

“What will it be?”

“You’ll see.”

When tea had been served in her room, she asked, “What do horses love?”

“Hay. Oats.”

“Yes. What else?”

Her eyes sparkled playfully. I followed her glance, and knew the answer.

“I know! Sugar!”

“Exactly” — and she made a little packet of sugar cubes in a Waldorf envelope from the desk in the corner, and my main concern about the trip to New York was satisfied.

At home I could not wait to present my gifts. Would they like them? Whether Anna and Mr. Schmitt did or not, I never really knew. Anna accepted her folder of views and opened it up to let the pleated pages fall in one sweep, and said, “When we came to New York from the old country I was a baby and I do not remember one thing about it.” Mr. Schmitt took his Statue of Liberty savings bank, turned it over carefully, and said, “Well. . . ”

But Ted — Ted very clearly loved my gift, for he nibbled the sugar cubes off my outstretched palm until there were none left, and then he bumped at me with his hard, itchy head, making me laugh and hurt at the same time.

“He likes sugar,” I said to Mr. Schmitt.

“Ja. Do you want to ride?”

Life, then, was much as before until the day, a few weeks later, that we received a cablegram telling us that my grandfather had died in Munich. My father came home from the office to comfort my mother. They told me the news in our long living room, with the curtains drawn. I listened, a lump of pity came into my throat for the look on my mother’s face, but I did not feel anything else.

“He dearly loved you,” they said.

“May I go now?” I asked.

They were shocked. What an unfeeling child. Did he have no heart? How could the loss of so great and dear a figure in the family not move him?

But I had never seen anything dead; I had no idea of what death was like; Grosspa had gone away before and I had soon ceased to miss him. What if they did say now that I would never see him again? They shook their heads and sent me off.

Anna was more offhand than my parents. “You know,” she said, letting me watch her work at the deep zinc laundry tubs in the dark, steamy basement, “that your Grosspa went home to Germany to die, don’t you?”

“Is that the reason he went?” I asked.

“That’s the reason.”

“Did he know it?”

“Oh, yes, sure he knew it.”

“Why couldn’t he die right here?”

“Well, when our time comes, maybe we all want to go back where we came from.”

Her voice contained a doleful pleasure, but the greatest mystery in the world was still closed to me. When I left her, she raised her old tune under the furnace pipes, and I wished I was as happy and full of knowledge as she was.

My time soon came.

On the following Saturday, I was watching for Mr. Schmitt and Ted when I heard heavy footsteps running up the front porch and someone shaking the door knob, as if he had forgotten there was a bell. I went to see. It was Mr. Schmitt. He was panting and he looked wild. When I opened the door, he ran past me, calling out, “Telephone! Let me have the telephone!”

I pointed to it in the front hall, where it stood on a gilded wicker taboret. He began frantically to click the receiver hook. I was amazed to see tears roll down his cheeks.

“What’s the matter, Mr. Schmitt?”

I heard my mother coming along the upstairs hallway from her sitting room.

Mr. Schmitt put the phone down suddenly and pulled off his hat, and shook his head. “What’s the use?” he said. “I know it is too late. I was calling the ice plant to send someone.”

“Good morning, Mr. Schmitt,” my mother said, coming downstairs. “What on earth is the matter?”

“My poor old Ted,” he said, waving his hat toward the street. “He just fell down and died up the street in front of the Weiners’ house.”

I ran out of the house and up the sidewalk to the Weiners’ house, and sure enough, there was the ice wagon, and still in the shafts, lying heavy and gone on his side, was Ted.

There lay death on the asphalt pavement. I confronted the mystery at last. The one eye that I could see was open. Ted’s teeth gaped apart, and his long tongue touched the street. His body seemed twice as big and heavy as before. His front legs were crossed, and the great horn cup of the upper hoof was slightly tipped, the way he used to rest it in ease. In his fall he had twisted the shafts that he had pulled for so many years. His harness was awry. Water dripped from the back of the hooded wagon. Its wheels looked as if they had never turned. What would ever turn them?

“Never,” I said, half aloud. I knew the meaning of this word now.

In another moment my mother came and took me back to our house, and Mr. Schmitt settled down on the curbstone to wait for people to arrive and take away the leavings of his changed world.

“Richard,” my mother said, “don’t go out again until I tell you.”

I went and told Anna what I knew. She listened with her head to one side, her eyes half closed, and she nodded at my news and sighed.

“Poor old Ted,” she said, “he couldn’t even crawl home to die.”

This made my mouth fall open, for it reminded me of something I had heard before, and all day I was subdued and private. Late that night I woke in a storm of grief so noisy that my parents heard the wild gusts of weeping and came to ask what the trouble was.

I could not speak at first, for their tender, warm, bed-sweet presences doubled my emotion, and I sobbed against them as they held me. But at last, when they said again, “What’s this all about, Richard? Richard?” I was able to say brokenly, “It’s all about Ted.”

It was true, if not all the truth, for I was thinking also of Grosspa crawling home to die, and I knew what that meant now, and what death was like. I imagined Grosspa’s heavy death, with one eye open, and his sameness and his difference all mingled, and I wept for him at last, and for myself if I should die, and for my ardent mother and my sovereign father, and for the iceman’s old horse, and for everyone.

“Hush, dear, hush, Richard,” they said.

A pain in my head began to throb remotely as my outburst diminished, and another thought entered. I said bitterly: “But they were black! Really they were!”

They looked at each other and then at me, but I was too spent to continue, and I fell back on my pillow. Even if they insisted that snowflakes were white, I knew that when seen against the light, falling out of the sky into the dark water all about the Kronprinzessin Cecilie, they were black. Black snowflakes against the sky. Black.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now