I don’t know what you have to do to have somebody buy you a drink in this neighborhood. In the old days, when the Logan Squares won, Owner poured a drink for everyone. When Hippo Vaughn pitched, he bought even if Hippo lost. Now it’s all changed. Now the good times are gone. Now Owner stops when he gets to me.

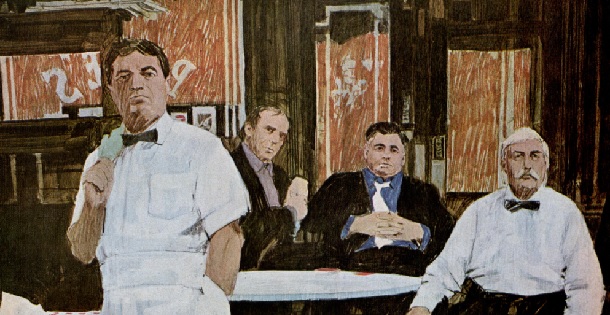

One night we were getting ready for four-handed poker — Owner, Fielder, Haircut Man and myself. Lottie-Behind-Bar was behind bar. Fielder kept shuffling a red deck.

“Last night I dreamed — ” Fielder began.

“No dreams,” Owner ordered him. “Deal.”

“I was leaning on the rail, I got a big ticket in my hand,” Fielder told, “only it don’t say what race. Don’t say what track. Don’t say Win. Don’t say Place. Don’t say Show.”

“For how much?” I asked.

“Don’t say for how much. Horses are in gate. Flag goes down.”

“What distance?” I asked.

“Don’t say what distance. My horse busts out in front. Cuts to rail. Two lengths out! Three! Pulling away!”

“How do you know it’s your horse?” Haircut Man wanted to know.

“In a dream,” Lottie called across the bar, “you don’t have to have all written down. When you want horse to pull away, horse pulls away.”

“Deal, deal,” Owner said.

“Skoronski is riding. Coming into backstretch, Skoronski stands up in the irons.” Fielder stood up and hollered. “Whip him in, boy! Whip him in!”

He slammed the red deck against the blue.

“Sit, Wenceslaus,” Lottie told him gently.

Fielder sat. And just sat — head down, holding the cards without knowing he held them, the red against the blue.

“You’re breaking the decks,” Haircut Man told him.

“Then stops,” Fielder said, like sorrowing. “Skoronski stops.”

“Stops?” Haircut Man asked, nervous like it had been his dream.

“No,” Lottie protested. “Not even Skoronski could get away with that.”

“All stop, Mother,” Fielder insisted. “Stop like when on film somebody is cranking, then suddenly stops cranking. Film stops. Horses stop. Skoronski stops, Mother.”

“Next time you see somebody cranking something, ask for a job before he stops,” Lottie told him.

“Jocks climb off. Kneel like track stars!” Fielder was getting excited again.

“Two bits Skoronski wins on foot,” I said, and put my last two dimes and four pennies in front of Haircut Man.

“What’s the distance?” Haircut Man asked before he took the bet.

“Hundred yards to finish line!” Fielder told us. “I climb rail! I’m running for Skoronski!”

Two hundred eighty-five pounds. When he sits, chair screaks. When he walks, floor screaks. He’s running for Skoronski. I took my 24 cents back.

“Bang!” Fielder shouted. “Bang!”

“Bang?” I asked, “How did a gun get into this?”

“He got to carry one so nobody steals his paycheck,” Owner guessed.

“How I run!” Fielder shouted. “Away from all! Like the wind, the wind, the wind! Right across finish line!”

“Where did Skoronski go?” I asked.

“No!” Fielder cried out. “I am Skoronski!”

“Play cards, Wenceslaus,” Lottie told him.

Fielder sat down. And looked so pale, so pale.

The game began as it always began; the cards fell as they always fell.

A wind came up as the wind sometimes does, and the rain began as it always does. The juke played what it always played.

And we said the things we always said, and the barflies drank what they always drank.

And the blue-and-red beer sign over the door flicked on, flicked off. Dead bulbs and bad wiring make it hard to see who comes in that door.

The kid called Lopez came in with the papers and left the door open behind him. Lopez is either a grade-school dropout or a 54-year-old disbarred jockey. Nobody knows which.

“Shut the door behind you, kid,” Owner said.

I watched Lopez reaching for the door handle, standing inside so as not to get wet. The light over the door flickered out, and somebody came in.

Came in without walking around Lopez, and stood in the shadow of the juke.

Lopez closed the door. “Race results?” he asked.

“No horse players in here,” I told him.

“Then buy a paper to put on your head,” Lopez said. “It’s raining outside.”

Nobody else had seen the one who came in. The blue-and-red light flickered on again.

“What are you going to do with your money? Be the richest guy in the cemetery?” Lottie asked Haircut Man when he won a hand.

“Mind the bar and shut the mouth,” Owner told her.

“Watch how you talk to my mother,” Fielder told Owner.

“You tell me how to talk when you can pay for your own drinks,” Owner said. “Don’t worry. I see all that goes on.”

“So do I,” Fielder said, like under his breath. “All.”

“You keep mouth shut,” Lottie called across the bar.

“When Haircut Man gives me a job,” Fielder let Owner know, “I won’t spend one dirty nickel in here.”

Haircut Man said nothing. But Fielder’s chance with him had come and gone.

“Fielder,” Haircut Man told him ten years ago, “come to shop at eight o’clock. I learn you haircut business.”

Fielder made it to the old man’s shop at two in the afternoon, so drunk he had to sleep it off in one of the chairs with his outfielder’s glove across his face. All he’s done since is sell gum at doubleheaders. Takes his mitt along in case of a foul.

Who remembers when Fielder played? Who remembers Fielder, a boy like a deer?

“Where you going, old man?” Owner asked when Haircut Man got up.

“To wash face,” the old man told him.

“To put his money in his shoe, he means,” Lottie said, after the old man had shut the washroom door. Haircut Man wears Ground Gripper shoes. If he would put shoe trees in them, they wouldn’t turn up at the toes.

I was dealing when he came back from the washroom. “You look bad, old man,” I told him when he sat down.

We all had our cards in hand before he picked his up. He picked them up and began squeezing one card at a time. When he got to the fourth, he let one card fall to the table. Then another, then another. The last two fell to the floor. His head went forward on his chest.

“Wake up, old man!” Fielder reached across the table, caught Haircut Man’s wrists, and began to rub them. “Old man! Wake up!”

Owner ran behind Haircut Man’s chair to take him under the shoulders.

“Telephone! Telephone doctor!” Fielder shouted, taking up the old man’s feet. “Keep head down!” he told Owner.

“Feet down!” Owner shouted at Fielder, but they went up, so Owner grabbed the ankles and pushed. Fielder yanked the body out of Owner’s grip.

He carried Haircut Man all the way to the pinball machine and stretched him out face down with his heels against the scoreboard. Then — so sudden, fast like a fish — Haircut Man flip-flopped so his face turned up. I thought he looked better that way myself.

I saw the one who’d come in standing behind the juke. He had his cap over his eyes.

Owner tried to get a fresh hold of the old man, but Fielder pushed him back.

“I think he is suppose to go the other way, Wenceslaus,” Lottie decided.

“Why do you always take his side, Mother?” Fielder asked, and began massaging Haircut Man’s chest.

I didn’t think the old man looked right myself, with his shoes against the GAME COMPLETED Sign, but I don’t like to take sides.

“Massage his feet, you,” Fielder ordered me.

I began rubbing fast, with both hands, taking care not to pinch the toes. The old man never done me harm.

“Not the shoes, dummy! The feet, the feet,” Fielder hollered right at me. I don’t mind being hollered, but not right at.

I unlaced one of the Ground Grippers. When I got it off, I looked inside. Then I took off the sock and held it up, but everybody was so busy watching Fielder massaging, nobody would even look at my work. I took the sock over to Lottie.

“What do I do with this?” I asked her.

“Don’t give me no dead stiff’s sock,” she told me.

“How do you know he’s dead?” I asked her, and up jumped Owner from the bar stool.

“Call a doctor!” he hollered. “Call a doctor! Maybe he ain’t!”

“Sit down,” Lottie told him. “I already called Croaker.”

“The old man owed me a drink,” I told her, hanging the sock on the bar rail in case somebody wanted to shine it someday. “You can give it to me out of his estate.”

“He didn’t have no estate,” Lottie decided.

“Not in his right shoe,” I said. “Do you think we should look in the left?”

“Here’s Croaker,” Lottie answered, and sure enough, some wax-moustache sport carrying a doctor bag was tipping the rain off the brim of his little felt hat into a spittoon beside the juke.

“Are you watering our roses,” I asked him, “or starting a reservoir?”

“Only being neat,” he told me.

“Buy me a drink,” I said, “and I’ll be on your side. You appeal to me.”

“I can’t afford having you on my side,” he told me. “Where’s the sick man?”

“Nobody sick in here I know of, Doc,” I told him.

“Look in the corner,” Lottie directed him.

“Corner of where?” He thought she’d said on the corner.

“I’ll take you there,” I told him. “I know this neighborhood like a book.”

Then he saw Fielder giving some- body a rubdown on the pinball ma- chine and walked over. He picked up the Ground Gripper I’d set on the GAME COMPLETED sign and studied it — the toe curved up like a ski.

“Have this bronzed,” he decided, and handed it to Fielder and came back to the bar. Fielder stopped massaging and came over too.

“Give this man a drink.” the Doc told Lottie.

“I got no glass,” I let everyone know.

“You don’t have anything to put in one neither,” Doc told me.

Some Doc.

“Let me introduce myself.” I thought he ought to know me better. “I’m the guy makes the people laugh. Watch this.” And I went into my song-and- tennis-shoe shuffle:

Take me down to Haircut Shop

But please don’t shave the neck

Call me up by Picturephone

But please don’t call collect.

He wasn’t watching. Nobody was watching.

Yet somebody was watching from behind the juke.

“I made the words up myself,” I told Doc. He didn’t answer, so I went around to where he could hear me better.

“You got a stet’oscope, Doc?” I asked him.

“In the bag,” he told me.

“I could help you test the deceased,” I offered. “Maybe there’s a faint murmur.”

“If there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s a stiff,” the Doc told Fielder, and took some sort of paper out of his pocket.

I knew what it was. I went around the bar and whispered to Lottie, “Don’t put it down he died in here. Owner might want to sell someday.”

Lottie whispered to Owner, and when the Doc handed over the certificate, Owner pushed a bottle at him.

“Don’t put it down he died in here, Doc,” Owner told him. “Put it down he dropped on the walk outside.”

The Doc crossed out a line and added one.

Owner signed. “I might want to sell sometime,” he explained.

“Do I get a drink now?” I asked Lottie.

Lottie brought a bottle up.

Owner took it down. “When we settle the estate,” he said.

“When will that be?” I asked him.

“When the dead come back from the grave,” Owner promised.

I dropped my jaw, made my eyes to stare, and pulled in my cheeks. What I call it is Making My Dead face. I pushed the whole thing into Lottie’s puss.

“What the hell is this for?” she asked me.

“It’s how you’re going to look one day,” I told her.

“It’s how we’ll all look one day,” she let me know.

I went over to Owner and made The Deadface. I made it deader than a real dead face.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked me.

“It’s how we’ll all look one day,” I told him. “Give me a drink while you still got time.”

“Who wastes whisky on the dying?” he asked me.

I went over to Fielder. He had the bottle in front of him and a shot poured. When he raised his elbow I put The Deadface up at him from under his arm. Fielder looked down at my Deadface looking up.

“Say a prayer for this guy,” he told everybody. And they all drank their shots down.

I went back to Owner. “How many?”

“How many what?” he asked me.

“You said you’d buy me a shot if I brought back the dead,” I reminded him.

“One shot is the limit,” he told me.

“I know,” I told him. “What I mean is, how many dead do I have to bring back to get one shot?”

Owner looked over at the pinball machine. “One will do,” he decided.

I went over to Haircut Man and whispered in his ear. “You got a royal flush, old man!”

He didn’t so much as stir. The old man was dead for sure.

I heard the Pulmotor Patrol sirening down Western, and a minute later two firemen came in, one carrying an inhalator strapped to his back. The other one unstrapped it and put the mask over Haircut Man’s face.

“Stand back. Back everybody,” he began giving orders. “If you’re going to lean over, put out your cigarette,” he told me. “We’re trying to give the man air.”

“Why should I give up smoking for you?” I asked him. “You don’t even come from this neighborhood.”

“Everybody back,” Fielder said, and put everybody back with one hand.

“If I can’t get up close to an accident,” I told Fielder, “I won’t look at all.”

I hung around, but not to look at the old man. Somebody had to watch those firemen because the old man had a gold ring on his right ring finger. Lottie came over to help me watch, and I decided to watch Lottie. I looked around and caught Owner watching me. There wasn’t anybody else left to watch the firemen except Fielder, and he was having a hard time because they were both watching him. I never saw so many suspicious people in one group in my life. When everybody got tired of watching each other, we all went over to the bar.

I stood between the firemen. They must have liked what they were drinking because they didn’t ask me to try it out for them. And every time they drank they’d touch glasses. It made me wonder what they would do about congratulating each other if they ever brought anybody to.

“That old man passed out in here seven times since Christmas,” I let them know, “and he came around by himself every time. Why would he stop at eight? If you fellows had kept your hands off him he’d be standing up here having a drink with us now. He was the best friend I ever had. He was like a father to me. I used to follow him to see he got home all right.”

“It’s a good thing he didn’t go down an alley,” one fireman told the other.

“Cops! We didn’t report this!” Owner suddenly thought.

“You want me to go for them?” I asked him. “I know where to find them.”

“Then what are you waiting for? Get them.”

“It’s raining,” I told Owner. “I need something to warm me up so’s I don’t catch my death.”

Owner made up his mind. “We got one stiff on our hands, we might as well have two.”

A Holy Father came in. One with a beard.

“I phoned for him,” Lottie said.

“You got the wrong kind,” I told her.

The Holy Father made some signs over Haircut Man. I went over, but it was hard to make out what he was saying. I slipped a dime into the pinball machine, and just as the Father crossed himself, the machine lit up. I scored 850 before Owner came over and shut it off.

“You said you were going for the cops,” he reminded me.

“What do I have to do to get a drink?” I asked.

“Put a sheet over him,” the Holy Father told Owner.

“How can I find cops with a sheet over me, Father?” I asked him.

“He doesn’t mean you,” Fielder told me. “He’s talking about our dead pal.” “Put a sheet over our pal,” Owner told Lottie.

“You don’t have to do everything the man tells you, Mother,” Fielder told Lottie.

“She don’t have to do anything she don’t want to,” Owner told Fielder.

Lottie touched Fielder with one finger, to shut him up, and went into the back room. She came out with a wrinkled sheet.

“You forgot your pillow, Mother,” Fielder told her.

“If you need a package of Juicy Fruit, Father,” Lottie told the priest, look for my son in Cubs’ Park.”

“In the bleachers,” Owner put in. “They don’t let him sell in the grandstand.”

“If you’d stop telling people I sell gum, Mother,” Fielder told Lottie, “I’d stop telling them you’re my mother.”

“I don’t hold it against her,” Owner said. “We all make mistakes.”

Fielder put up his fist, as big as Owner’s whole face, right under Owner’s nose. Owner didn’t even blink. He just put his hand on the bar towel and waited until Fielder’s knuckles touched his nose. Then swish — smack across Fielder’s face with the towel.

Fielder grabbed the towel. Owner let go of it. And there was Fielder wiping his face with the very towel that had just smacked him.

Lottie kept tucking the sheet around Haircut Man so she wouldn’t have to take notice of the events across the bar. One corner of the sheet said HOTEL MARK TWAIN in green letters.

“Know who that is?” I asked the Holy Father, pointing at the signed photograph of Jim Vaughn above the bar. “That’s Hippo Vaughn from the Chicago Cubs. Nobody had to say to Hippo, ‘Buy me a drink, Hippo.’ Hippo didn’t wait for that. He poured it for you, and put a fiver in your pocket whether you asked for it or not. Anything Hippo had you could have.”

The Holy Father wasn’t listening.

Lottie put my cap on my head. “Take a run for the cops,” she told me, and the way she said it, I decided I would.

Look for cops on a rainy night the same way you’d look for a cat — somewhere out of the wet and cold, next to a wall or under a shed. I went down the alley behind the Krakow Bakery, because that’s where it’s always warmest. They were parked with a cardboard box over the flash, listening to Pat Suzuki singing her heart belonged to an older man. Outside of that and being parked wrong, they were keeping crime at bay by smelling rye bread. I rapped the window, and one cop rolled it down. He looked scared, like I was going to pinch him.

He was Firebox, a fellow I went to school with. He’d gotten his start by running for the truant officer to break up crap games after he’d lost his lunch money. Later he took to ringing fireboxes to see the hook-and-ladder go by, and it looked like he’d get on the fire department. He got caught once, but got off because he promised never to do it again — gave his word. And he kept his word so good they put him on the cops. He has a good record there, too. On the force twenty-two years, and never made a pinch. You never know where talent will show up next.

“Come and get a dead guy,” I told Firebox.

“Who shot him?” he asked me.

“Nobody shot him.”

“Then how do you know he’s dead?”

“Because somebody put a sheet over him, and he didn’t pull it off.”

The other cop woke up. “That ain’t our jurisdiction,” he told Firebox.

I know this one too. We call him Transistor because if he catches you with a stolen one he don’t turn you in. He just takes it off you, and you can buy it back for what it cost in the store you stole it from. It’s better than getting busted.

“What do you want us for?” Transistor wanted to know.

“Go get a dead guy out of a place,” I told him.

“Try the fireman’s carry,” he told me. “We’re crime fighters, not litter bearers.”

“I think we ought to take a look,” Firebox decided, and I knew what he was thinking. “Where is this stiff?”

“Carefree Corner. You know — Owner’s joint.”

“Where Fielder hangs?” Transistor asked.

“Fielder sent me.”

“I caught Hippo Vaughn,” he told me. “Get in.”

I got in the back seat and away we go.

“You don’t look like Bill Killefer to me,” I told Transistor.

“I didn’t say I was on the Cubs,” he told me. He meant he caught Hippo for the Logan Squares, after Hippo’s big-league days were over.

“Fielder was fast, them days,” he said.

“He isn’t fast anymore,” I told him.

“I know,” Transistor said. There was a crowd in front of Owner’s. Firebox went inside and right up to the pinball machine, and pulled back the sheet and began running his hand across the old man’s skull.

“What’s he doing?” Lottie asked me.

“Looking for bullet holes,” I explained.

“He wasn’t shot,” Lottie told Firebox. “He had a coronary.”

Firebox began running his hand up along the old man’s spine.

“He’s still looking for bullet holes,” I told Lottie.

“The man had a heart attack,” Lottie told Firebox.

“Why didn’t you say so in the first place?” Firebox said. Transistor began stuffing the old man’s shirt back down into his pants. You never can tell where a stiff is likely to wear a money belt.

“What is the deceased’s name in full?” Firebox wanted to know. “Put down any name you want,” Owner told him. “Just don’t say he died in here.”

“We might want to sell sometime,” Lottie explained.

“Where do you get that ‘we’?” Owner asked her.

“Don’t worry, Mother,” Fielder told Lottie. “You still have your pillow.”

“A 40-year-old son,” Lottie told the Holy Father, “and he sells gum.”

“What did you say the old man’s name was?” Firebox repeated.

“He didn’t have no name,” I explained. “We just called him Haircut Man.”

“What’s your name?” Firebox asked me.

“I don’t have one neither,” I told him.

“They just call me ‘You.’”

“Then stay out of this, You.”

“If you want the old man’s name,” Owner spoke up, “maybe it’s in his wallet.”

“See what the name in the wallet says,” Firebox told me.

“See what the name in the wallet is,” I told Fielder. “I’m not working for the Department myself.”

“Mother was the old man’s best friend,” Fielder offered. “Maybe she knows his real name. Then nobody has to look in his wallet.”

Cops are careful about reaching for a wallet on a drunk or a stiff. If the wallet is empty, they get the blame.

The kid, Lopez, was still there, with one newspaper left. Firebox lifted him up level with the old man. All he had to do was reach.

“I can’t,” Lopez yelled, kicking with both feet.” If I reach I’ll drop my paper.”

I took hold of his paper, but Lopez locked it under his arm. “If you want the paper, buy it,” he hollered.

Firebox put a dime in his little paw, and Lopez let go of the paper and reached and got the wallet. He hung on to it while Firebox carried him to the bar. The wallet didn’t bulge, and when Lopez held it upside down six trading stamps fell out. He shook it. That was all.

“Look inside,” Owner told him.

Lopez opened the wallet wide, stuck his nose into it, sniffed into the corners, then took his nose out.

“Gone on the arfy-darfy,” he announced, and Firebox set him down.

I started my soft-shoe bit.

What do you want for the little

you got

For the little you got you don’t

got a lot

You kept your money in your

big dirty shoes

From the graveyard who collects?

Nobody was paying me any attention. Nobody ever does.

“Who would have thought the old man would die broke?” Lottie asked Owner, looking him right in the eye.

“My own opinion,” Owner answered, “is that he didn’t.” And looked me right in the eye.

“Ambulance!” Lopez hollered, before any of the rest of us heard a siren.

Firebox looked down at him. “Where’s my change?”

“What change?” Lopez asked, looking up.”

I give you a dime for your dirty yesterday’s paper. I got three cents coming, Shorty.”

Lopez don’t like being called Shorty. “I don’t have change,” he told Firebox.

“People pay you in seven-cent pieces?” Firebox asked him.

“Why don’t you search him, Firebox?” I suggested.

“He can frisk me, but he can’t search me,” Lopez let the Department know.

A dozen people followed the stretcher-bearers in. Owner put two bottles on the bar and got ready to pour. It looked like a good night for Owner. But no one came near the bar. They all wanted to help the stretcher guys carry the stiff to the dead-wagon. The stretcher guys wouldn’t let them. All they could do was follow the stretcher out.

I stood by the bar, next to the Holy Father. I was trying to remember whether Haircut Man was still wearing a ring the last time I looked. If he was, one stretcher-bearer was in a good position to get married. All he needed was a blind whore.

“Were you a friend of the deceased’s?” Firebox asked Lottie.

“Hardly knew the old man,” Lottie said fast.

“I thought you knew him well, Mother,” Fielder put in. “I thought he said he always helped you out when you weren’t working.”

“Why should I take money from strangers when my son works steady?” Lottie asked him straight.

“All right,” Fielder said. “All right, Mother. I know you worked for me all my life. Now why don’t you go out and get a job for yourself?”

“My son sells gum,” she told the cops, and put her face down on her arms on the bar. I don’t think she was crying, because I didn’t hear a sound. She just moved her shoulders a little. Owner touched her shoulder, and she looked up.

“Wenceslaus,” she said to Fielder. “How God is going to punish!” Then she put her head down again.

Fielder got up from the table where our poker game had been. He began walking toward the calendar that hangs on the washroom door. When he got there, he just stood and looked at it Then he took the mitt out of his hip pocket, put it on, and swung at the calendar. The calendar bounced and the door shook. Then he swung again.

“I am Skoronski!” I heard him say to himself. Then the calendar fell, and Fielder just stood there, with his back toward us, pounding his fist into his mitt.

“What do we do now?” I asked the Holy Father.

“Let’s try it three-handed,” the Father suggested. He picked up the cards and began shuffling slowly.

And as the cards began to fall, I knew, without looking at the juke, that there was nobody behind it anymore.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now