Timothy stood at the fountain, his hand inside his coat pocket rubbing two quarters against one another. He’d walked past this fountain on his way to work at the library hundreds and hundreds of times and had never thrown his money in, but today he did think about it. Although, what would he wish for? There wasn’t anything to wish for exactly.

He had gotten up in the middle of the night, as usual, getting a bleary-eyed drink of water in the dark and visiting the bathroom, and realized only in the morning that he had not heard the sound of his cat Bipsy’s paws trotting behind him. She was old, but still she followed him everywhere. How had he not noticed the absence of that particular sound? It was as though he had failed to notice the stopping of his own heartbeat.

He’d felt all strangled inside when he figured things out. Now what? he’d kept thinking as he made the coffee and packed his lunch for work in silence. Now what?

Author, Author!

Don’t miss new books from Great American Fiction Contest authors:

• 2013 Winner Lucy Beldsoe, A Thin Bright Line (UW Press, 2016)

• 2015 Winner N. West Moss, The Subway Stops at Bryant Park (Leapfrog Press, 2017)

• Judge Michael Knight Eveningland (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2017)

Timothy looked up at the branches of the London planetrees overhead in the park and could see birds everywhere, busy busy busy. April was the right time for them to be swooping between treetops and lampposts, hopping on the ground for muffin crumbs. He mourned never learning their names. His mother and brother had known the names of birds, but he’d never latched on. They could tell one song from another, could look up at the under-wing of a bird lofting up like a kite against the blue sky and say “peregrine falcon” or “turkey buzzard” in hushed and intimate tones to one another. He was never part of their circle but had watched from the side, a tiny little circle of his own, intersecting nothing.

Timothy could tell a seagull (white) from a crow (black) from a cardinal (red). He’d studied an illustration of a stork in a Hans Christian Andersen story, but his knowledge wasn’t advanced enough for him to be certain whether or not there was a difference, say, between a crow and a raven, or between a stork and an ibis, a heron or an egret. Heron and egret and ibis and stork might all be different names for the same thing, as far as he knew.

It was too late now to wish for the intimacy of family. His mother was decades gone, and his brother had gone off to Kuwait a long time past, and had come home essentially gone years before he’d died. Something had shaken his brain loose is how Timothy had pictured it, and everything that had been his big brother had effervesced like the escaped air from inside a popped bubble.

The loss of Timothy’s cat made the loss of his brother fresh again, made the absence of the whispers between his brother and mother echo, reverberate as though Timothy were standing in an enormous, empty room. They had been easy friends with one another, his mother and his brother, but Timothy hadn’t decoded the language of their intimacy. Their closeness had been like a promise of eventual closeness for Timothy that he could not bring to flower.

The birds around him now were babbling. April was cruel, he thought, just as Chaucer and Eliot had promised back in college. The flowerpots in the park were full of hyacinth and daffodil bulbs, their buds bursting up through the dirt like aneurysms. The bunched buds swelled up and unfolded their redolent petals until they sagged open, calling to bees. He could almost hear the birds above puffing out their chests, their songs like screams, hopping onto one another’s backs to fight or mate. The park was positively indecent with procreation.

He sank, contented in his own invisibility, and watched.

Just do it, he told himself, and took both quarters out. Plash and then plash. He didn’t wish for anything, just thought Bipsy and then Bipsy as each coin sank beneath the water and rested on the cool stone bottom.

Timothy hid his face down inside his coat’s collar as he walked around the fountain and onto the gravel path. He knew that beneath his feet were the two floors of library stacks, what had been called the Bryant Park Stack Extension, that the employees of the library called BIPSE. It’s how he’d come to name his cat. It was spectacular down there, well lit and every inch waterproofed, a self-sufficient world of temperature and humidity controls, filing cabinets, microfiche, and moveable shelves. And 26 feet below that (he had been told) there was a stream, carving its way through the cold dark rocks that held the city up.

If you turned it all upside down, there was as much unseen beneath New York City as what lay on top of it. And as much inside each person Timothy passed as all of it combined.

He sank inside his own indistinctness and walked past the new sod, rolled out each April after the skating rink was heaved up, packed on trucks, and put into storage for another year. At the 40th Street loading dock entrance to the library, he held up his ID card. Manny said, “Morning,” and Timothy raised his hand in a wave, curling up the corners of his mouth to approximate a smile.

His little desk seemed far away as he slipped down the side stairs where he wouldn’t likely see anyone, through a door where he had to swipe his ID card, down the long white hallway (more like a brightly lit tunnel) and past the vault where special books were held. He wasn’t allowed in the vault, with its John James Audubon original double-elephant folio from the 1800s, and William Blake’s engravings from Songs of Innocence and Experience from the 1700s, touched by the artist’s very own hands. Blake had written “A robin red-breast in a cage/puts all Heaven in a rage.” Timothy knew what robin redbreasts looked like. They were self-explanatory. There were documents in that vault that were so important that Timothy wasn’t even allowed to mention them. And the people allowed in the vault had to wear white cotton gloves if they meant to touch anything.

Down and down he went, where the smell of reinforced spines of old books on thick paper reached him like violets. He could breathe here. And think. The only noise, the hum of the purring temperature and humidity controls. As the space grew narrower, Timothy felt better. Down he went to the second floor (the lower of the two), edging his way between the wall lined with microfiche cabinets and the stacks to where he had arranged his desk to be maximally hidden. Finally he was alone.

He had a coat rack that the guys in the carpentry shop had given him where he hung his coat, umbrella, and briefcase. When he’d first gotten the job, almost 40 years earlier, his mother had made him one of those little stamped labels with his name on it, and so Timothy’s full name was glued near the handle of the briefcase. Every time he saw it he felt a soup of nostalgia and pity for his mother, so long gone, and for himself too. He knew it was sad for a man in his 60s to carry a briefcase with a label from his long-gone mother that was peeling up at the edges. But what was he supposed to do? Pry the label off and throw it out? For what? For whom?

He sat down, turned on the computer, and straightened out the NYPL pins he had arranged at the base of his desk lamp, representing his 10, 20, and 30 years of service. He was due another pin soon. Then he downloaded the book requests he’d received. It was only 9 a.m., and there was an enormous list of books to pull and send upstairs. It would be a blessedly busy day.

Later, as he was eating his cheese sandwich and checking for new requests, he heard a shout approaching from far away. “Timmy!” It was Lloyd Calaban, he of the glossy black hair and easy laughter. Everything seemed so easy for Lloyd, who was able to glide through life without worrying, it seemed. It was hard to imagine Lloyd, for instance, waking up at three in the morning, suffocating from loneliness. Timothy was aware that his own pallid face and high-arching eyebrows could discomfit people. He tried to soften his face, to make himself look less surprised by squinting his eyes before Lloyd came around the corner. The squinting sometimes helped, but the way his hair had thinned and receded made him look like a sinister clown. Timothy stood up to meet Lloyd, and then thought better of it and sat back down. Too eager.

“I know you’re here somewhere,” Lloyd called.

“Yes,” Timothy croaked, standing up and then sitting down again, clearing his throat. “I’m here!” He tried to sound as though he’d been speaking to people all morning. Lloyd started around the corner, all smiles, and Timothy met him with a sudden wanting-to-be-known-by-him. He wanted to tell Lloyd, for instance, that he had a collection of 73 antique bookmarks at home, and that he knew how to play the recorder, and that he had eaten caramels at his aunt’s farm in upstate New York one summer as a boy, but he said nothing.

He felt especially isolated around Lloyd’s expansiveness, which trumpeted out ahead of him like a red carpet that Lloyd himself rolled out wherever his feet went. Timothy wanted Lloyd, or someone, to know how much he loved his job, and that he’d had a cat named Bipsy for 17 entire years, and that he was encouraging to her about how pretty she was, and how safe he’d keep her. He wished Lloyd could have seen them together watching Jeopardy! every weeknight, Bipsy on the back of the couch, reaching out one paw and resting it on Timothy’s shoulder.

Lloyd came toward him like a sun shower. “Tim-MAY! How’s it going, man?”

“Oh, just fine. Busy morning.” He couldn’t think of anything else to say, felt a blush coming up his face.

“Listen,” said Lloyd, “could you help me out? I’m being pulled in a million directions, and Melanie needs this, in her hand, ASAP.”

Timothy reached his hand out for the request slip. “I’d be happy to,” he said.

“She’s mad at me,” said Lloyd, grinning, leaning against the metal microfiche cabinet. “Fixed me up with her sister and, well, you know, those things never work out, but I want to give her time to cool off, and she wants this, like, yesterday, you know?”

“Yes, yes, I can do it for you.”

“But, like, you have to do it now, buddy. I’m sorry to ask you to do this. I’m sure you’re in the middle of other stuff.”

“It’s no problem at all,” said Timothy, heat rising up through his cheeks and past his pale, high eyebrows.

“I owe you one, buddy,” said Lloyd, pointing his finger like a gun at Timothy and winking. “I owe you one.”

“No, no,” said Timothy, beaming. He loved the idea of Lloyd owing him one. When Lloyd had gone, Timothy tried out the gun hands, and then went to find the book that Melanie needed. She was efficient, Melanie was — neither friendly nor unfriendly, but busy and no-nonsense. She was important, had to deal with board members and donors. If she needed this book right away, he’d get it for her. He felt like Superman.

“I’m on my way,” he said under his breath, giddy, rushing to the stacks. There he pushed the button that separated the shelves from one another. He could hear the mechanism whir as the shelves slid apart, creating an aisle for him. Timothy’s focus was laser sharp as he ran his finger along the numbers on the shelves until he came to the right place, pulled the cardboard sleeve out, and found Melanie’s book. He put the request slip inside the front cover, hugged the book to his chest, and rushed out of the stacks and up toward the public part of the library, his pulse racing.

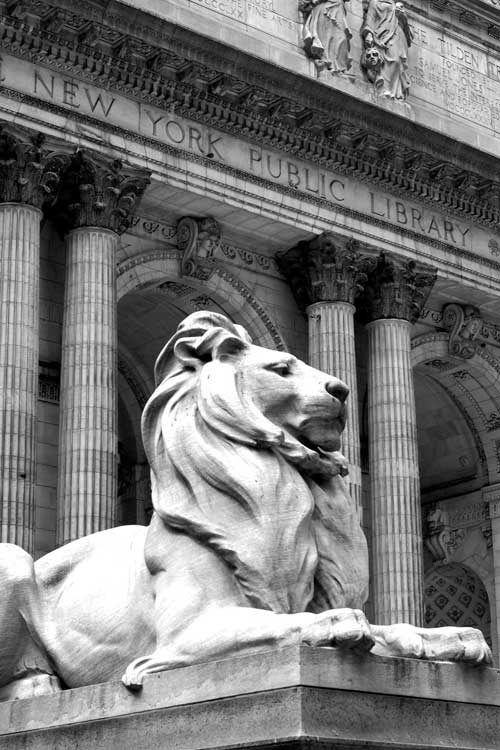

Timothy walked quickly through the tunnel, up one set of stairs and the next, and then over to the main part of the library, just below the first floor. He slowed as he reached the busy lobby toward the Fifth Avenue entrance near the famous lions, Patience and Fortitude, and stopped near the top and peered up into the crowd of people; the guards at the revolving door checking bags, the sunlight pushing weakly in, the homeless man who came in every lunchtime and slept in the reading room for an hour, and dozens and dozens of people looking up and zigzagging unpredictably in and out toward the main exhibit, or up the stairs or toward the gift shop, just like the birds in the park.

He blinked and tried to soften his face, knowing that he would look spectral to anyone who turned and saw his pale, startled head floating there. He imagined how scary that might look and forced himself to keep moving up. And as he thrust himself forward up the final stairs, his shoe-tip caught the lip of the top step.

And he flew.

For just a moment.

Up through the air.

In slow motion.

Melanie’s book flew, too, up above him, the pages fluttering, and he thought how the book looked like the bone in 2001: A Space Odyssey tumbling end over end. Timothy reached his hands out as though he were an athlete of some kind, a quarterback maybe, and caught the book as he slid under it along the stone floor and came to a halt, his eyes shut, his heart pounding, time returning to normal speed. He could hear people gathering around him cooing, and wished he could melt away under the eyes that he felt staring down at him.

“You all right?” It was a woman’s voice nearby. He opened his eyes. A pale 50-ish woman leaned over him, her eyebrows knit in worry, her lips a bright matte-orange slash in the middle of her face. Her hands were fluttering like moths around him. She knelt down next to him, and for the second time that day, he felt a blush rising up in him as he lay there clasping Melanie’s book. “You okay?” she said, patting his hand.

She’d touched him. He became very, very still. “You okay?” She was smiling and he felt a surge of love well up in him for the pumpkin orange of her lipstick and the way she had no real chin, and for her hands, trembling like birds’ wings do when they are in a birdbath.

He blinked once, twice. “My cat died last night,” he told her. There, he’d said it, and could feel the ribs in his rib-cage loosen.

She leaned closer and her lips made an O. “She was curled up in a ball this morning, her tail over her nose.” And then, as though she had asked him a question, he said, “Bipsy. I called her Bipsy.”

The woman smiled.

“She was 17 years old. I got her after 9/11 from the pound.” His mouth felt very dry, and he stopped talking and blinked up at her. He should probably try to get up. He wondered if he should tell her that, not knowing what else to do, he had finally put the cat in a plastic Food Emporium bag and thrown her down the garbage chute, but he decided to keep that to himself.

“Hey,” she said, still smiling down at him, but starting to unkneel. “Hey! I know you!” Her eyebrows came together as she tried to figure out where she knew him from. “Yes, yes, I know you.” His heart quickened, and he felt tears in his eyes. She knew him? She knew him. “You threw money in the fountain this morning. I saw you.” She had seen him, and she saw him now. She could see him.

She laughed and held out her hand to help him up, and the crowd that had gathered backed up a step.

“I saw you is all,” she said. “What are the chances of that, that I’d run into you twice in one day in this city?” She turned to no one in particular and said, “What are the chances of that? I see this guy throwing money in the fountain this morning, and the next thing I know, he falls right at my feet in the library?”

The group was dispersing, but a few responded by shaking their heads or murmuring to one another before turning away. He felt all their circles intersect, or felt the pull of their now-separating circles.

The woman with the orange lips said, “Maybe I’ll see you around.” She smiled a real smile that made her eyes crinkle up, and she touched his shoulder. “Crazy city, right?” He nodded and blinked against the wetness in his eyes.

Timothy slipped behind one of the massive columns to peek back around at where he had just been lying, at the way the sun poured in over the moving people, how every second was like a snapshot, a new one each moment.

He should have told her about how he could play the recorder, and about the caramels he’d eaten at his aunt’s that summer in Upstate New York. But memory was a kind of accomplishment in itself. And if he’d run into her twice in one day, perhaps they’d be thrown together again. He rested his cheek against the cool marble pillar. He remembered, then, why he was upstairs, and he hurried to deliver Melanie’s book to her.

As he passed the fountain on his way home that evening, he stopped again. Way back on 9/11, he had almost thrown money in. That had been the only other time he’d even considered it. The subway stops at Bryant Park. That’s what people always said, but on 9/11, when they let everyone out early from the library, he had crossed through the park on the way to his Hell’s Kitchen walk-up. It was at the fountain that he’d become aware of the lack of sound and vibration under his feet. The subways weren’t running for the first time in his whole life, and there was a stillness he couldn’t fathom, like a penny dropped down a well that never splashed.

There had been no way into or out of the city that day, and he had stood in the silent park with a handful of pennies ready to throw into the fountain as a gesture against hopelessness, but he’d been waved away by the National Guard with their guns, everything deranged and toppled together in his mind. The fires and the fallen towers smelled like burning rubber, and like concrete smashed into bits light enough to float, and like the scent of unsettled souls. Were there particles of people in the air? Of course there must have been.

His awareness of the silence of the stopped subways beneath the park had never dissipated, and now it got layered beneath the missing sound of Bipsy’s paws thumping down off the couch behind him. The space of her absence would make a palpable presence of its own, like the repercussive silence of the subways, and the music of his mother and brother whispering the names of birds back and forth, call and response, while he stood apart and listened.

N. West Moss was the winner of the Post’s 2015 Great American Fiction Contest for “Omeer’s Mangoes,” which, with “Absence of Sound,” appears in her first short-story collection, The Subway Stops at Bryant Park (Leapfrog Press, 2017). This story first appeared in Neworld Review. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, McSweeney’s, and Brevity, among others. For more, visit nwestmoss.wordpress.com.

This article is featured in the July/August 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now