For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

The back to school letter from Congdon did not bring good news. The enrichment program at Endion was supposed to be for two years: fifth and sixth grade. But yet another revolution in educational theory had hit Congdon, and the school pulled the five of us smarty pants out of the program, so we could enjoy all the benefits of the new system.

A modern extension had been wadded on to the old brick school building for Congdon fifth and sixth graders; we were to be the guinea pigs for a new “modular” elementary education. Someone had finally realized that teachers who graduated from college before World War II, and whose educational ideal was a pin-drop quiet classroom with seasonally decorated bulletin boards might not be capable of instructing students in higher math skills or science that wasn’t a slowly dying terrarium. Miss Ritchie, I’m afraid they were looking at you.

Instead of a single classroom teacher, we now had four, each one with a specialty: English, Social Science, Math, and Science. The new teachers were all under forty and to our shock, two of them were male—I didn’t think men were allowed to be elementary school teachers. The teachers each had their own room with new lightweight desks, so we had four different desks to keep our stuff in. Since each class of students moved from room to room during the school day, none of us except the most anal of twelve-year-old girls ever had the right books, pencils, or writing paper for the class we were in. The first ten minutes of every class was spent repositioning our desks in small groups or a big circle or in rows, or an original configuration, if the teacher could think of one, with chair legs screeching against the linoleum, and “ouches” and “ows” as we banged into each other, jockeying for position next to the most popular kids. The next ten minutes was spent scrounging for supplies that had been left in the previous classroom. Under this new regime, art and music fell by the wayside. I guess the amount of time we had spent in previous years creating shoebox dioramas and learning to sing “White Coral Bells” as a round was considered adequate.

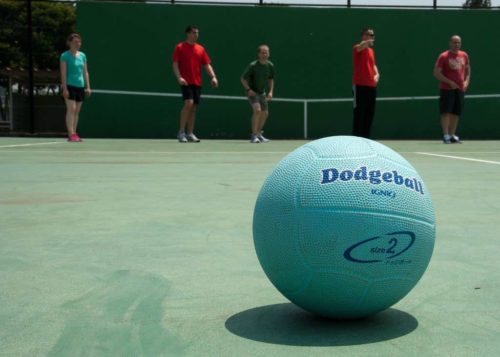

The male teachers took over gym, and competitive games ruled. Out went square dancing, in came high velocity dodgeball. I was not only always chosen last, but also managed to get hit as soon as possible by placing myself directly in front of the first ball languidly tossed over by a girl on the other side. In this way I avoided being concussed by one of the boys’ vicious fastballs, and I got to spend gym period sitting dreamily on the sidelines, missing my wonderful enrichment class and imagining I was watching the Olympics in ancient Greece before strolling down to the Acropolis. During one particularly brutal game, when it got down to two players on each side, husky Mr. Levine, nominally our math teacher, pointed at Billy Shaw and called “Out!” to which Billy Shaw replied “F**k you, Mr. Levine.” Mr. Levine charged Billy like a freight train and proceeded to beat the shit out of him all around the gym. The rest of us huddled together, like wildebeests watching one of our own being devoured by a lion, and tried to get as far away as possible from the pummeling. This incident did not result in a dodgeball ban, or even in a reduction of the fierceness of the competition, which remained at major head injury level; there was just less audible cursing from the boys, and I continued to be able to avoid getting any exercise in gym.

For the first time in our collective student memory, there was a new girl in our class. Becky Sweet, a blonde so slight and pale she looked in danger of toppling over, was a pro at being the new kid: her father was a minister of some obscure Nordic-based Protestant denomination and was assigned to a different Minnesota town every few years. Becky had vast experience in recognizing which girl needed a friend the most and lit on me as her new best friend. I had never had another kid choose me for anything before, and fell into best friendship without a thought.

Becky was obsessed with sex and George Harrison and had the oddest family life I had every seen. She would not come to my home, but insisted that I sleep over at her house every Friday. I never once met her father. His work took him all around upper Minnesota and Wisconsin, driving to small farm towns to stand in for ministers who had dropped dead or shot their wives or been caught tampering with the livestock. Or he was at church, counseling parishioners, or rarely, in his study, NOT TO BE DISTURBED.

Becky’s mother was also a ghostly presence. I would catch a glimpse of her when I walked into their house, wafting from room to room before vanishing into her bedroom. Becky and I were left with her older sister, who supervised the making of huge bowls of popcorn, dinner for the three of us, washed down with Hawaiian Punch, about as transgressive a dinner as I could imagine. Then a car pulled up, a boy shouting and blasting the horn, and big sis would take off for the night. Becky and I settled down on her couch to watch the Friday Night Fright Fest, old black and white sci-fi movies where radiation would create giant women, tiny men, and plants that could walk and eat people. When the Duluth broadcasting day ended at midnight, Becky and I climbed into her bed, back to back. I fell asleep listening to her explicit fantasies about having sex with George Harrison, the important details of the act having been supplied to her by her sister. Had I met Becky the year before, I wouldn’t have cared about missing the “Becoming a Woman” educational film and I would have been voted Most Knowledgeable About Sex at Camp Wanakiwin. Becky’s obsession was almost innocent: she didn’t try to touch me and I don’t think she touched herself. Unlike the other Beatle-crazed girls I knew, Becky didn’t press me to pick a favorite Beatle. I was the audience for her stories about George Harrison and his undying lust for her pre-pubescent body To me it was far from erotic; it was just another piece of Becky’s Bizarro World, like the missing parents, the wooden crosses on every wall, and the fridge that held nothing except can after can of Hawaiian Punch.

These Friday nights were a dark, musky secret at the heart of our friendship. My mom was too busy with an infant and a missing six-year-old to ask about my sleepovers at Becky’s, so she never knew about the popcorn dinners, staying up until midnight, or the lack of adult supervision. Since Mrs. Sweet never seemed to leave the house, she was far out of my mother’s social orbit; mom felt no compunction to invite Becky to sleep over at our house, as she would for a daughter of a matron of long Duluth standing. Becky never showed the least desire to come to my house; a real dinner might have been a serious blow to her digestive system.

Then in the spring, Becky was gone, her father sent off to another parish. Because I had been away from Congdon at the enrichment program for half the year during fifth grade and held in isolation by Becky Sweet for most of sixth, I was now completely friendless. I read, watched TV, held my baby sister, and kept an eye out in case Lani reappeared.

***

The street where I lived, Lakeview Avenue, was on the very border of zoning for two Junior High Schools, Ordean and Woodland, so I could opt to go to either one. I was the only one in the Congdon sixth grade to occupy this geographic odd spot; all of the other kids lived in the Ordean zone and were headed there.

I took stock of my friendless state and decided that I needed a fresh start. I was the four-eyed bookworm, the eternal teacher’s pet, the kid you did not want on your dodgeball, volleyball, or softball team. But if I went to Woodland Junior High, I could re-invent myself! I could be a woman (girl) of mystery. Girls would want to whisper to me about other girls and pass notes about which boys they liked, and boys would want to walk me home, carry my books, and hold my hand. I could be cool.

My fantasies were not unlike Becky’s. Somehow she would meet George Harrison and he would be smitten with love for her. Somehow I would enter Woodland Junior High and be popular. Before our pre-school shopping trip to Minneapolis, I pored over Seventeen magazine, noted that grape and rust were the in colors for fall. From the “Back to School” racks of clothing I carefully selected skirts and dresses in those hideous shades, all at a slightly above knee length, as I had been instructed by Seventeen. My mother, the shopaholic and former beauty queen, was delighted that I was turning into a real girl.

I thought I was ready to conquer Woodland Junior High, an uninspired white brick two-story building, bland as boiled rice on the outside; inside held a disturbing whiff of chlorine from the pool and all the miseries of being a pre-teen girl. The boys contributed their own smell: sweat, Clearasil, Right Guard, and the Jade East cologne worn by sophisticated ninth graders. This smell permeated the halls we streamed through, every hour, year after year, as we traveled from one classroom to the next.

I had been overconfident in my ability to transform myself; the scratchy new sweater the color of Welch’s Grape Jelly and the coordinated plaid skirt were not enough. Clothes do not make the seventh grade girl, a lesson I seemed incapable of learning.

The first morning of Junior High was filled with the excitement and confusion of a hundred new students trying to find their different classrooms, prompted by a confusing buzz of the school bell every fifty minutes, overseen by bored teachers trying to determine if you were in the right class. When the noon bell sounded, I followed the seventh grade shift of lunchers into the gigantic cafeteria.

I waited in the endless school lunch line and wished I had brought a packed lunch, looking out at the tables already crowded with kids pulling sandwiches out of brown paper bags. When I finally got my tray I stood in the center of the cacophony in my new duds, grinning like Alfred E. Newman, and waiting for someone to wave me to their table. My stomach and my heart squeezed together as I realized that my plan was not going to work. All the girls already had their cliques from elementary school; new comers need not apply. And I am sure that not a single seventh grade boy noticed that I was dressed out the pages of a Seventeen magazine.

I tossed the contents of my tray into the garbage and spent the rest of the lunch hour weeping silently in a bathroom stall.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for sending this chapter – I don’t want to miss any of them. For what it’s worth, I thought you were pretty cool in high school.

I remember the principal at Ordean Jr High slamming guys up against lockers.

The way Gay can tickle a memory nerve Is uncanny!!

Gay

They say you can spot a kid from catholic school, by the way they act. I went to Saint John’s for eight grades where you had one class room and one teacher who usually was a nun. Seems the nuns did not need any teaching abilities and trust me, none of them did. So going to Woodland was like another world. I new next to nothing in most subjects. The catholics thought that if you knew religion you could fake the rest. Wrong. I started out bad and never recovered.

The modular experiment was put into play at Chester Park elementary also. For ALL of the students. If you were highly motivated and disciplined it worked well. For the remaining 80% of us it was an utter failure. I eventually succeeded academically, but after 6th grade I thought I was dumb.

Thanks for triggering so many memories from my time at Woodland. From the nascent intellectual excitement of reading Oedipus Rex, The Hairy Ape, Ghosts and the like in a “phase 8” English class of ten with a brilliant young teacher to the downright weirdness of 40+ boys swimming nude in gym class, the Woodland Junior High experience provided something new, crazy and potentially awkward to anticipate each day.

Mike Cohen:

Not enough students to justify 2 jr.high schools in East district. Instead of building a new HS, Ordean was expanded and became the new East; Old East became the only jr.high or middle school, now 6-8

I remember the great 6th grade experiment well. It continued for us in 7th grade at Ordean. I almost flunked out since we had so little supervision. And i do remember the teachers bouncing us around when we smarted off. Phil (Carelton) offered to fight one if he “took off his brass” Lucky for Phil he couldnt get his wefding ring off.

Heartbreaking ending! And sadly so universal.

There I was at Congdon with you and I had two male teachers before the experimental team teaching in 6th grade. I had Mr. Anderson for 4th grade. He’d been shot in the eye with a bb gun as a kid and it was still lodged in there, so he was just too cool. And in 5th grade I had Mr. Downs. I still vividly remember him breaking down when the Principal came on the PA and announced that President Kennedy had been assassinated.

Of course after Congdon I headed to Ordean while you headed to Woodland, only reunite at East HIgh.

Oddly, Ordean has been converted and is now East HIgh, and East High has been converted and is now a Middle School. I’ll never understand that one.