For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My dad would shake his head over the Cs on my report card from gym and home ec, ignoring the As in math, history, science, and English (Bs in Spanish); did he not know who I was? I had always excelled at anything that required brain power; ask my fingers or legs or arms to do something, and I was as helpless as an earthworm.

My grades were good enough that my parents had no compunctions about pulling me out of seventh grade for a week. A dental convention in Mexico City was the tax-deductible impetus for a tour through Acapulco, Taxco, and Cuernavaca. My dad thought the exposure to a foreign culture would be good for me. Heidi was not yet two, and Lani, as usual, was the middle child afterthought: they got left at home with the sitter. I, the smart one, the lucky one, the anointed, flew south with my parents and grandparents.

My father’s favorite thing was to travel without hotel reservations. I was not on the trip to the New York City where my parents had to spend the night in a second-floor walk-up hotel in Harlem, back when Harlem was Harlem. I was on the family skiing trip in Wisconsin over a holiday weekend, when we drove for hours in the dark, passing one neon NO VACANCY sign after another. In the middle of the night we finally stopped at a hunting lodge that had closed for the season, but whose owners had stayed on. By a miracle this lovely old couple were awake and felt sorry enough for the exhausted-looking family to let us spend the night in one of the unheated cabins. They even made us breakfast.

This, however, was an American Dental Association trip, which meant fancy hotels, bus tours, and meals at restaurants where the most Mexican item on the menu was a margarita. In Acapulco my parents and I were given a luxury two-bedroom suite at the El Presidente hotel, as evidently the roll away bed had not yet been introduced to Mexico. Floor to ceiling windows looked out over the famously beautiful Acapulco Bay, a vision I thrilled to again while watching the first season of I Spy, and then, eight years later, from the balcony of a high-rise condo, while making out with a playboy from Chicago who was twenty-two years older than me.

My first day in Acapulco I was pulled sputtering and floundering out of a fierce undertow by a sharp-eyed dentist while my own dad was getting drunk at the bar. Heavy drinking Minnesota dentists plus cheap Mexican booze equaled a non-stop party that started in the morning with Bloody Marias and ended when someone got hurt or sick. Dentists were jumping off roofs into pools, getting into fistfights, laughing so hard on burro rides they pissed themselves. I was the only kid in this group, and as I was small and quiet (even when drowning) I went as unnoticed as a salt shaker, even by my own family.

I finally piped up during a drunken dinner at a fancy restaurant when I saw a flaming baked Alaska cross the room and was struck that here was the height of sophistication. Cake, ice cream, meringue, and a fire! If only I had a baked Alaska of my own I could die happy. I was certain that my request would not be granted: the usual answer to “Can we have dessert?” at a restaurant alternated between concern for our teeth from my father and “We have ice cream at home” from my mother. But my dad was tipsy and in a benevolent mood and my mom was too busy worrying about what drunken dental hijinks were in store that night. I felt like a princess when the waiter set the blue-flamed baked Alaska in front of me. It was Neapolitan ice cream set on a slice of chocolate cake, surrounded by hot, sticky, marshmallow-y goo, and it was delicious.

The last day in Acapulco the dentists who were not too hungover and their wives gathered around a open space between the hotel and the beach to watch three men dressed as Aztec warriors fling themselves off a 40-foot pole, anchored by vines knotted around their ankles. While I watched agog as they twirled around the rotating pole, I overheard two dental wives discussing the night before. Little pitchers do have big ears. A taxi driver had offered to take some of the dentists and their wives to see a “show” at a whorehouse.

During the show, one of the group, in a perfect storm of drunkenness, decided to participate. But it was a not a dentist, but Mrs….here the woman’s voice dropped to a whisper, so I’ll never know which of the wives, hiding behind the cat’s eye sunglasses and under ugly straw hats purchased for way too many pesos from the voracious beach vendors, women who were sun-burned or coping with Montezuma’s revenge or hungover or all three, which of these demur ladies had ripped off her clothes and jumped on to the stage at the whorehouse and into the arms of the leading man.

Once away from the Acapulco nightlife, the dentists dried out and recuperated in Taxco and Cuernavaca, pretty colonial towns with pastel houses covered in bougainvillea, that featured boring tours of silver and pottery stores. In Taxco my father stepped off the tour bus and, instead of heading for the air-conditioned hotel for lunch, took me into the most flyblown, dingy restaurant on the plaza. We sat by the greasy front window at a table as sticky as flypaper, even though miraculously the 500 flies buzzing around our heads seemed able to resist setting down there, preferring to wait till the food arrived. As my dad was ordering the enchiladas suizas (how did he even know what that was? The only Mexican food I had seen in Duluth was in a Swanson’s Mexican Style TV dinner, where every brown component in the foil tray tasted the same), my mom and grandmom appeared at the open doorway, afraid to step inside in case germs clung to the soles of their shoes. Both moms ordered us to get out of there and not touch anything. I dutifully obeyed, but my dad just grinned and tucked into a huge platter of green and white something, while the waiter stood behind, waving off flies with a menu. My grandmother turned bilious just looking at the enchiladas; my dad finished the whole thing, burped, gave the waiter the equivalent of 90 cents, and felt absolutely fine.

My mother was not so lucky. She not only got sick from almost everything she ate, she had a terrible reaction to the smallpox vaccine the Dental Association recommended she get before traveling south of the border. She spent the night of the big formal gala at the actual convention in Mexico City puking and watching her arm swell up to the size of an elephant’s trunk. I was sent off to find my dad at the party, which was held on the top floor of our fancy hotel. He refused to leave, being several margaritas in and, never having experienced any illness himself outside of killer hangovers, didn’t believe anyone could get sick from a shot. I grabbed some food off a tray and went back to our room, my book, and the scary sounds emanating from the bathroom.

I was now a sophisticated world traveler. I had been out of the United States! I never missed an opportunity to mention my travels, until even my best friend Wendy finally asked me to shut up about Mexico. But summer camp provided a whole new audience. I embellished my travelogue for my bunkmates, giving myself a handsome 16-year old Mexican boyfriend, Andres. In this new version, it wasn’t a balding orthodontist from Edina who pulled me out of the undertow in front of the El Presidente hotel, it was Andres, who then fell instantly in love with me, a reverse Little Mermaid. I spun a tale of Andres sneaking into our suite when my parents were out; how we would make out passionately on the sofa overlooking the lights of the bay. I confessed that Andres tenderly tried to stick his hand under my shirt, but I held him in check, despite his protestations of undying love. I told and retold the story of my imaginary romance so often that I almost came to believe it myself. For the two weeks of camp, I was the most popular girl in our bunkhouse, and even the counselors looked at me as if I might be interesting.

I came back from camp that seventh grade summer, basking in my fraudulent role as resident boy expert and sadly aware that I didn’t want to go to camp anymore. What if all of those camp girls who boasted of boyfriends and their extensive knowledge of sex were just big fakers too?

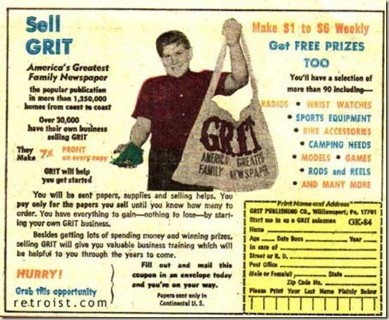

I had just gotten home when Wendy called to tell me that she had overheard Rick Bryers (one of my heartthrobs) and Steve Puloski talking about me. Two boys who knew I was alive? I couldn’t imagine what they had to say. Could they possible think I was cute? Wendy in all her innocence or malice, told me “Rick told Steve he had seen you at the Northland pool” (my racing thoughts: I did look adorable in my first two-piece suit, a red and white Hawaiian floral, what was Rick Bryers doing at Northland Country Club and….HE NOTICED ME AND KNEW MY NAME) “and Steve” (who was universally despised by the entire seventh grade for many reasons, including putting Fizzies in the biology teacher’s fish tank and showing up at all of our houses trying to sell Grit magazine or packages of seeds or greeting cards) “Steve said to Rick…flat as a board, huh?” After that there was a roaring in my ears. I hung up the phone and vowed I would never go to school again.

But I did, and eighth grade followed seventh as if it were Ground Hog Day: I was the star pupil in English, math, science, and even boring Minnesota state history. I was still chosen last when sides were picked for volleyball (why couldn’t the gym teacher simply divide the class in two?) and still regularly forgot to bring my gym uniform to school. I endured a second year of being taught useless domestic skills in home ec. I forgave Wendy for squashing my dreams of true romance with Rick Bryers and spent as many weekends as I could at her weird dorm apartment. We’d flip through that month’s Seventeen magazine, debate the merits of Napoleon vs. Ilya, review every comment made to us by a boy during the past week for signs of infatuation (“When he asked me what the caf had for lunch, did he want to sit with me?”), and try to figure out what the popular girls had that we didn’t (which was, in the end, their popularity, which made everything else — their clothes, their hair styles, their manner of speaking — admirable and something to emulate). We were two glasses-wearing, violin-playing nerds, but we had each other.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’m sure having that blue-flamed baked Alaska set in front of you by the waiter DID make you feel like a princess! It’s a great picture by the way, Gay.

My parents took me and my younger sister to Mexico when I’d just finished 7th grade in June 1970. Acapulco was a lot of fun, and the warm ocean water felt wonderful. The unexpected tide had me sailin’ away on the crest of a wave and I was lucky I didn’t drown.

“I went as unnoticed as a salt shaker” is a very nice line.

I don’t know Wendy from Adam, but I love her. Your Wendy was my Effie.