For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

In 1967, my eighth grade summer, the sixties finally trickled up to northern Minnesota. Up till then, we had existed in our own little insulated pocket of intact families, nosy neighbors, regular church-going, casual drunkenness, and a sincere belief in the virtue of conformity. Children were seen but not heard, teens were just big kids waiting to become adults, God was in his heaven, and all was right with the world.

Somewhere in the South people were marching for civil rights. Duluth had virtually no black people. We had a few grizzled Indians hanging around the liquor stores, waiting to buy booze for teen-agers in exchange for a few bucks or a can of beer. We had a handful of Jewish families, who were regarded suspiciously by my mother, although she had jumped at the chance to dump her two youngest kids in a half-day preschool at the Jewish Educational Center, where Lani, and later Heidi, learned to play the dreidel and build Sukkot tents.

Men were burning their draft cards in Berkeley and New York City; Walter Cronkite led off the news with stories of the war in Vietnam. But the college deferment was still in place, which meant that no boys who grew up in my neighborhood were at risk of being shot at by those awful Viet Cong.

Teen culture had started to seep in with the Beach Boys. But the California world of surfing and woodies seemed as exotic to us as an Indonesian dance troupe on Ed Sullivan. Our one and only radio station, WEBC (AM of course), played Top 40 music in an indiscriminate scramble: on a 15-minute drive to the store, we would hear “Ballad of the Green Berets,” “Monday, Monday,” and “Born Free.” When the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” came out, WEBC beeped out the title line every time, in the interest of public morality.

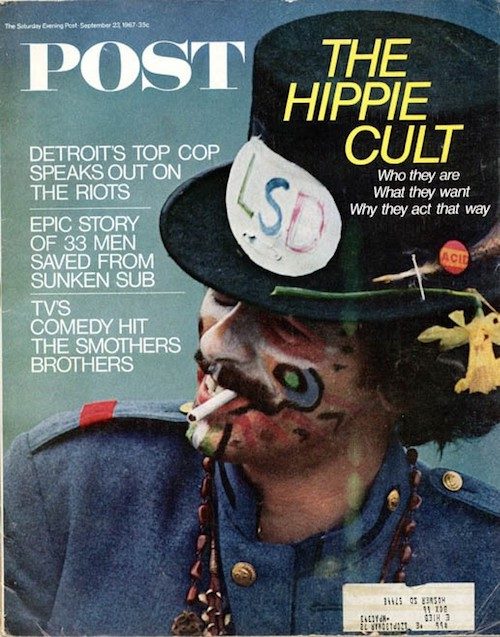

But cracks were opening up. Time and The Saturday Evening Post, which arrived weekly at our house, increased their coverage of civil rights and anti-war protests, and I began to tilt left. The TV shows Hullabaloo and Shindig! moved away from Petula Clark and Bobby Darrin and towards the Doors (sex!) and Jefferson Airplane (drugs!).

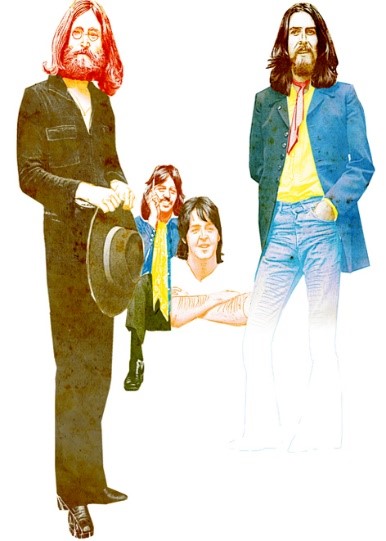

Drug culture took longer to reach us, too damn long as far as I was concerned. I had never succumbed to Beatlemania; the unwashed, sneering Rolling Stores were much more exciting. But it was mandatory that if you were between the ages of 13 and 21, you went gaga over the release of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I happily joined in, hoping that by listening to “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” I could get an aural contact high.

Somewhere, out in the real world, people were smoking marijuana and banana peels, ingesting morning glory seeds and LSD, expanding their consciousness in all kind of ways. But I was in a basement in International Falls, sitting around a tinny hi-fi system, with Sgt. Pepper on repeat and repeat, the record coming to a scratchy end and then flipped over, while the boy who lived there was dissolving Bayer aspirin in bottles of Coca-Cola, in an attempt to get himself and his pals, which included me but not my disapproving best friend, Wendy, high. We all claimed to feel something, although what I mostly felt was sick to my stomach.

I was huddled on that basement floor because that summer I was a long-term guest at Wendy’s grandma’s house. I had outgrown camp and the Northland Country Club pool. After the mandatory visit to Aberdeen, where I spent two weeks reading and sulking, my mother gratefully sent me north and out of her hair. International Falls was a small town, a lot like Aberdeen, but smellier, thanks to the paper mill. Wendy and I were regarded as sophisticated big city girls — “Wow, you live in Duluth!” —and welcomed everywhere. The day after the aspirin experiment, we were invited to a taffy pull at a neighbor’s, something I thought existed only in the pages of a Laura Ingalls Wilder book. My hands were buttered to the wrist, as if I were to be part of an adolescent orgy. The taffy was white and ropy and smelled of vanilla, and when finished was tooth-achingly sweet and tooth-shatteringly brittle. My father would have been horrified. I was annoyed at this wholesome party activity; I wanted to be back down in that basement, listening to records with boys and figuring out ways to get high.

I also participated in a bizarre experiment in reversing Down Syndrome. Wendy’s best friend before me had a baby sister with Down’s. I didn’t quite understand what was going on with this big-headed kid who couldn’t talk. The mom, searching for a cure, had fallen under the influence of a crack-pot theory that held that crawling was the basis of all subsequent learning. The mom spent hours manipulating her baby’s arms and legs in a swimming/crawling motion. When she got too tired she recruited anyone within shouting distance to take her place. I have no idea whether it helped or not. It was horribly creepy, moving the baby’s right arm and left leg for ten minutes, then switching to the left arm and right leg, while the kid made noises somewhere between a chortle and a howl. I hated going over to that house of sadness and madness.

The kid with the basement and the aspirin and the Sgt. Pepper’s album was International Fall’s leading Bad Boy. Wendy and I adored him. Several weeks into my visit, all of us 13-year-old aspiring juvenile delinquents were hanging out on a street corner, trying to be much cooler than we actually were. Bad Boy was smoking a cigarette (oooh!) and started lighting matches and tossing them into a red and blue mailbox. Of course, we found this, as everything Bad Boy did, hysterical. At about the twentieth match, smoke began seeping through the mailbox slot. All of us stood gazing horrified as the wisp became a serious plume, a “Yeah something is really burning” smoke signal. One of Bad Boy’s friends helpfully noted that we had probably committed a federal crime, setting the U.S. mail on fire. As the smoke darkened and streamed out of the mailbox, we fled in all four directions. Wendy and I bamboozled her poor grandma with some story about why we had to be back in Duluth immediately, and pooled our money for bus tickets, hoping to stay one step ahead of the law.

***

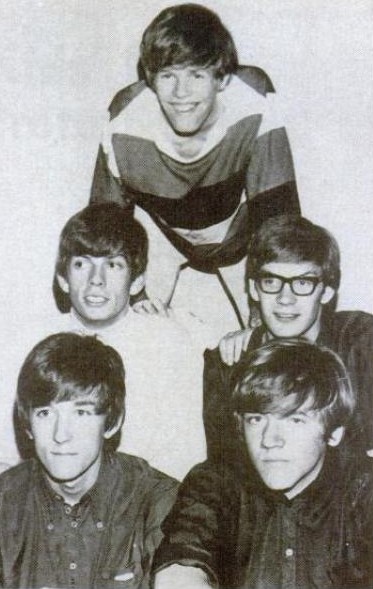

I got back to Duluth to find the entire teen universe abuzz. The Duluth auditorium, which had opened in 1966 and been home to hockey games, Ice Capades, and the Ringling Brothers Circus, was to have its first rock concert: Herman’s Hermits.

Wendy and I were speechless with joy. While Herman, aka Peter Noone, the lead singer, was almost a little too preciously adorable for my tastes (always a smile, never a sneer), he was undeniably cute. And I, like everyone under 25 in the country, had fallen under the perky, head-bobbing spell of “I’m Henry the Eighth, I Am,” which was played by the radio station at least once every hour, causing pre-teen girls to squeal, hop on one foot, and shout out “Second verse, same as the first!”

For weeks before the concert, I was lost in a whirl of daydreams where Peter Noone looked out in the audience, saw my adoring face, and fell madly in love. He would send someone out to escort me backstage, take me in his arms, kiss me, gently remove my clothes…and then stuff would happen that I was still having a difficult time imagining. I would get to that crucial point, sigh, and rewind my daydream back to the beginning.

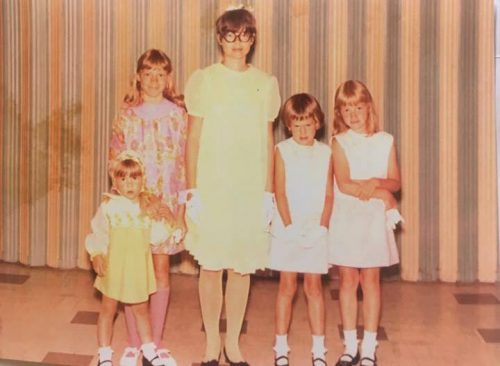

There was only one problem. I wore glasses, thick, hideous glasses which could kill the sex drive of any boy at ten paces. I could go to the concert without wearing my brown cat’s eye with sparkles (an improvement over the baby blue ones I had worn for years) but then I wouldn’t be able to see a thing onstage. How could I catch Peter Noone’s eye if he were just a fuzzy object? I wouldn’t even be able to tell him from the lesser, unnamed Hermits.

Shindig!, the TV music show, saved me. It was on during a school night, so Wendy and I had to watch it at our own homes, one ear glued to the phone, discussing which bands and boys we liked. Shindig! had a troupe of cute girl dancers (now there was a career!). One of these dancers wore, along with her mini skirts, Mondrian-inspired dresses, and go-go boots, a pair of perfectly round tortoise shell glasses. Thanks to some mysterious seismic movement or an alignment of the stars, a pair of those exact glasses showed up at my eye doctor’s, where before my choice had been between the baby blue or shit brown cat’s eyes with sparkles. My mother, the slave to fashion, was always delighted when I paid attention to what I wore and how I looked — which was still, with my badly cut mousy blonde hair, not good. But at least with my outrageously stylish new glasses, I commanded some attention from boys, most of it a startled reaction of “Weird.”

With my Shindig glasses and my own Mondrian color block mini dress, I was ready for Peter Noone to sweep me off my feet. I don’t remember what Wendy was wearing. It didn’t matter, she was only there to report back to all of Woodland Junior High that I was not in ninth grade because I had eloped with Herman.

My dad, who had been known to whistle “Henry the Eighth” himself occasionally, scored us seats a few rows from the stage. We had to sit through an opening act before Herman’s Hermits came on. That band was The Who. I had heard “I Can See for Miles” on WEBC a few times the winter before, enjoyed it, but relegated The Who to the category of British Bands I Kinda Liked: The Kinks, The Animals, The Zombies.

Seeing The Who live rocked my little Duluthian world. There I was, nicely dressed, waiting to see that sweet young man who politely told Mrs. Brown she had a lovely daughter. I got Roger Daltrey’s unhinged vocals (ooh, he was really cute!), Keith Moon’s spastic flailing over his drums, and Pete Townsend smashing his guitar on the stage floor over and over (and John Entwhistle noodling about in the background). The Who killed off any residual Minnesota nice girl in me and I was pitched head first into full-fledged Youth in Revolt. At the end of “I Can See for Miles” Townsend stomped offstage with the splintered neck of his guitar in hand while everyone around me politely applauded while muttering “Were they on drugs? What was that all about?” I knew what it was about, it was about smashing the old to make way for something completely new, whether the world or Duluth or Woodland Junior High was ready for it or not.

The crowd stood and roared when Herman’s Hermits took the stage; I was still in a daze; sorry Peter Noone, you are no longer my type.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Can’t believe I missed that show, but being it was summer we were always gone to Itasca where my father taught at the UM extension camp. Bummer.

I still remember that concert. Fantastic show.

My goodness Gay, you just couldn’t get away—-from that crazy summer of ’67, could you? Bayer aspirin in Coke bottles, a 19th century taffy pull, figuring out way to get high in the basement–with boys?!

What kind of a Disneyland of perversion are we talking about here, my dear?? A short strange trip revealing YOU were hanging out with a “bad boy” lighting matches and discarding them into the U.S. mail box–only for a fire to start inside?? Of course it’s a federal crime! I’m Henry the Eighth, and I say “off with her head–but let me keep those glasses; I dig the Shindig look–ya dig man”? I’m into something good!

Have you? Have you had some kind of mushroom, and your mind is moving low–or high? No mushrooms, Alice; they could be poisonous to a girl. Is there really a hippie on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post? HELP!!

************

“Sweetheart, wake up! It’s Dad, you were having a nightmare. It’s that darn Sargent Pepper album, I know it is. From now on it’s Magical Mystery Tour for you, young lady. By the way, you can take off those beautiful cat’s eye glasses with the sparkles when you’re sleeping. Good night honey”.