For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

My first date with Michael Vlasdic had a few glitches. Duluth teen culture was car culture. With your friends a car was a party on wheels. With a boy a car was a bubble of privacy, a place to make out, WEBC on low, heater on high, the windows opaque with steam. I, however, had only a learner’s permit; to get that required just a multiple-choice test on road rules, the kind of test I aced every time. I had barely squeaked through drivers’ ed, the instructor constantly taking over control and slamming on his brakes because I was unable to gauge distances between the car I was driving and everything else, other cars, pedestrians, curbs. I also had difficulties telling the brake pedal from the gas pedal. My sweating, pale instructor assured me that all I needed was more practice, but every time my mother let me take the wheel it ended quickly in shouts and tears. I was idiotically optimistic that when I took the road test in December, when I turned sixteen, I would magically pass, but for now taking the family car was verboten.

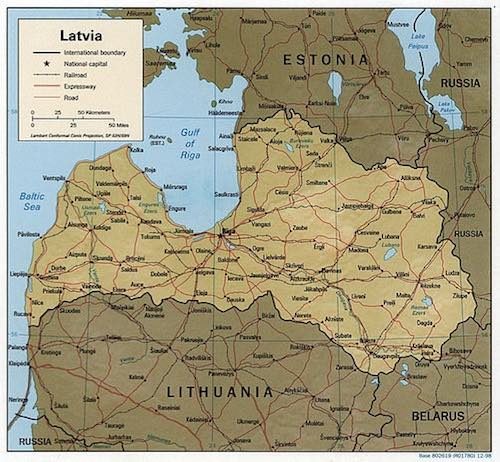

Michael Vlasdic lacked both a car and a father. His mother was originally from Latvia

(a country I knew only from volume L of my old World Book encyclopedia, which identified it as one of the Soviet Socialist Republics) and had moved to Duluth to teach German at the university. She was stately and Old World polite, with a solid-looking helmet of dark hair, and always in a boxy wooly suit, thick beige nylons, and sensible shoes. The missing deadbeat dad was in Mitchell, South Dakota; Michael once proudly showed me a postcard of a large yellow structure that proclaimed Greetings from the Corn Palace! that his dad had sent him. In lieu of money, I guess.

I had met a few kids without fathers, but a family without a car? Where could Michael and I go on our first date? You could not enter the London Inn parking lot on foot. You’d be a laughingstock.

On the phone Michael said, “Why don’t you come over here and we’ll listen to records?” I did not have a better idea, so that Saturday I walked the twenty minutes over to Michael’s house. His mother was out for the night. His mother was out a lot.

Michael and his mother lived in a small up-and-down duplex filled with books and cracked oil paintings in gilded frames, dark heavy furniture, more books, jewel-toned oriental rugs, potted plants, and more books. There was also the standard big cabinet hi-fi in the living room. Since there was no parent in the house, Michael and I went to his room to listen to music and so Michael could smoke a joint, which he did leaning precariously out the window. He offered me a hit, but I was afraid if I had my usual pot-induced coughing fit while straddling the windowsill I would plummet to the ground and that would be a hell of a first date.

We started talking, about music (we liked the same bands! Of course in 1969 every kid was devoted to Steppenwolf, Cream, Jimi Hendrix) then books (Michael had read The Lord of the Rings three times to my twice). A current of tingly magnetism drew us closer and closer together, and then there was a lot of kissing. Seated kissing, with our arms propped straight as crutches on Michael’s narrow, neatly-made bed, then lying down kissing, with arms wrapped around each other, bodies close enough together that I could feel him harden. Michael reddened with embarrassment, got up to take off his glasses, and we kissed some more.

Time played its elastic tricks: it stopped while we were kissing, then hurried forward, the clock rushing to eleven, my curfew, and I had to leave, with still the twenty minutes to walk home. Michael and I untangled, he found his glasses, but it was impossible for us to part. He walked me back to my house, through the still and silent streets, a thousand stars on a moonless Minnesota night twinkling down at the new lovers. Michael was bookish and shy, a proto-hippie like me, and charmingly unaware of how good-looking he was. On that walk we shared what secrets and history sixteen- and fifteen-year-olds could have accumulated. We marveled that the universe had contrived to bring us together, two pieces fitting into place in the cosmic jigsaw.

We kissed as long as possible in front of my house; I was just beginning to put the horrors of July 21st behind me. If my mother should have appeared in the doorway and started yelling, I felt I would die. I pushed Michael away, slipped into my sleeping house and floated up the stairs. In bed, I wrapped my arms around myself, imagining it was Michael who held me, I thought of the dirty books hidden away underneath me; the pages I had carefully dog-eared didn’t begin to describe the sweet ache I felt, a longing I knew Michael felt too. I wondered how long it would take us to go all the way.

It took a week. The following Saturday, up in his room, his mother attending another university faculty beanfest, our clothes half off and “Whole Lotta Love” urging us on, Michael told me he loved me. “I love you too,” I said, and it turned out those really were magic words, words that made it imperative that we get rid of the rest of our clothing immediately. It was Michael’s first time and I wished it were mine too. “Making love” and “having sex,” are such awful phrases for what we did. We were two young animals, playful, tender, funny, considerate, with wildly responsive teen-age bodies we smashed together as closely as possible. It was as if the two of us had invented sex, sex that was as transcendent and addictive as any drug.\

Adorable, innocent Michael did not have a condom, since he was even more unwilling than I was to go into a drugstore and ask for a package of rubbers, which in those days were kept locked up on a high shelf in the back of the storage room to extend the embarrassment of the foot-shuffling, eye-averting teenage boy waiting at the counter. (One particular wisenheimer druggist liked to yell out, “What size, buddy?”)

After our first time, I called an emergency sex consultation with my girlfriends, held in Linda Laurence’s basement. While taking sips from Linda’s parents’ collection of Bols after-dinner drinks (crème de menthe, crème de cocao, peach brandy, cherry kirsch, and other stomach-churning flavors) and everyone but me smoking cigarettes, we discussed how I could have as much sex as possible without getting pregnant. Alternative methods were suggested and met with peals of laughter, some real, some forced; these ideas were quickly discarded. Some of my gang did have boyfriends who braved the druggist’s stink-eye and the wait of shame at the Tru-Value Pharmacy, but you don’t ask your boyfriend if he can spare a rubber so some other guy can get laid.

We pooled our collective knowledge and misinformation about the female reproductive system. Linda plucked a calendar off the wall and we huddled over it, guessing at those days that might be safe and days I should definitely keep my panties on.

Pregnancy was the dark looming cloud that hung over rapturous teenage sex: everyone knew of the senior girl who had been sent off to a home for unwed mothers, returning after six months thin and wan and without a baby or a boyfriend. But despite regular scares, no one in our gang got pregnant or had any tragedy befall us. While we had scrapes and accidents, heartaches and breakups, for the three years of high school we lived in a teen fairyland, where we could have sex and not get pregnant, drive drunk in cars with no seatbelts without going through the windshield, and hop on and off moving freight trains without losing a leg.

Besides being considerate enough to go out almost every Saturday night, Mrs. Vlasdic thoughtfully taught class two afternoons a week. If it were the right day of the month Michael and I would dash from school to his house for the world’s quickest quickie. When Mrs. Vlasdic walked through the door at four o’clock, she’d find Michael and me at the dining table, fully clothed, surrounded by homework, and drinking tea. She had to have known what was going on.

My own parents had briefly met Michael and felt no reason to be alarmed: his mother was a university professor and Michael seemed too painfully shy and nerdish to be any threat to my already sullied honor. And at that point, my family was spinning apart.

After buying the big, impressive Hawthorne Road house, my dad spent less and less time there. My mom was taking a full-course load at the university, her youthful dreams of being an actress whittled down to a prospective career as a speech therapist. My younger sisters Heidi and Lani would have been latchkey kids, except we never locked our doors in Duluth; after school they walked the three blocks home together, let themselves in, and headed straight for the TV.

But even at its emptiest, my house was firmly off-limits for sex. I was haunted by the horrifying memory of Doug Figge trying to cover his balls with his hands, like Adam suddenly aware and ashamed of his nakedness. I wouldn’t feel safe having sex in my own home if both my parents were in Idaho.

On the Saturday nights Mrs. Vlasdic selfishly stayed home, we hopped in a car driven by Roger or Needle, Michael and I clutched together smooching in the back seat. We’d drive around Duluth for hours, the guys smoking pot or searching for someone to sell them pot.

I luxuriated in my membership in two high school groups: my gang of loyal, funny, raucous girlfriends, and the druggies of East High, whose numbers increased daily. We proclaimed our allegiance to the counterculture with long hair, fringed jackets, wire-rimmed glasses, beads, and bellbottoms. My pal Wendi Carlson became a fervent pot smoker and made it her life’s mission to teach me to inhale. She was even more disappointed than I was that I was still unable to draw the tiniest puff inside my lungs.

A member of the druggies was cute Stan Lewis, a year behind me, who showed up at all the parties with weed. Stan and I would find each other at these parties and swap what little we knew about psychedelics. Could you really get high from morning glory seeds or nutmeg? What was the difference between LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin? When you’re tripping, do you need someone straight around in case you freak out? How much did these drugs cost and where could we get them? I thought of Joe Sloan, who would soon be back in Duluth for Christmas, which reminded me of Doug Figge and the astronaut, so I lied and told Stan I didn’t know anyone who had those kind of drugs.

Stan, a determined guy, went out and found someone who did, and for my sixteenth birthday he gave me a small blue pill that he said was mescaline, supposedly not as mind-blowing as LSD. He handed it to me in the parking lot of the London Inn. I immediately popped that pill in my mouth, washed it down with watery Coke, and thanked Stan with a friendly kiss on the cheek, which I now suspect was not what he was hoping for. I jumped into the White Delight on to Wendi Carlson’s lap and whispered in her ear what I had just done.

There were no empty houses that night so my sixteenth birthday celebration was a three-hour auto tour of residential Duluth with six of my best friends. It was early December, pre-broomball season, but there were frequent stops for peeing in the snow and return visits to the London Inn to see if any cute boys were around. Wendi kept pinching me hard and asking, “Are you tripping yet? How about now?” and I kept shaking my head no.

I was somewhere around Hawthorne Road, on the edge of my front lawn, when the drugs began to take hold. I was sober as Judge Erman when I climbed out of the White Delight and headed into my house; I had not a single drink on my birthday, waiting for the mescaline to kick in and transport my mind to Peter Max world.

Just as I was thinking that poor Stan had been swindled, I opened the door to my house and was blinded by the hot-as-the-sun kitchen lights. I stumbled and braced myself up on the wall, which was wildly tilting, while a galaxy of neon geometric shapes swirled around me. It took me a minute to realize that the low frequency rumble I was hearing was my mother asking me how my birthday was. I slid into the living room doorway and made small talk to the elongated monster with snakes for hands that was sitting on the TV couch. I finally escaped and made my way up to my room and tripped for hours, staring out into the night, where twinkling snowflakes and yellow streetlights and the deep blue of winter created a hypnotic tapestry. I twirled the dial of my melting bedside radio, WEBC having signed off for the night, searching for music and unfortunately hit on a horrible station out of Chicago that chose to play “D.O.A.” by Bloodrock at 2 a.m. I listened to the whole thing, perched on the edge of madness, switched the radio off, and hid under my blanket until I stopped hallucinating horrible, bloody car wrecks and finally fell asleep.

I couldn’t wait to trip again.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Oh Gay, didn’t you ever hear, “Just say NO!” Good thing, otherwise I’d be spending this wet cold day with Netflix instead of laughing my head off at your “mem-wahs”. Keep ’em coming!!

I like the pictures you include in the various chapters, Gay. You kind of morphed from Michelle Phillips to Janis Joplin between Chapters 28 & 29.

I’m glad you didn’t smoke pot while in Michael’s room, or get pregnant, OR have a bad experience with the mescaline! It’s a good thing you got safely inside your house before the full effects of this hallucinating hypnotic tapestry kicked in.

I’m sorry the song you last heard before falling asleep was D.O.A. I’m sure ‘The White Rabbit’ by The Jefferson Airplane, or ‘Incense and Peppermints’ by The Strawberry Alarm Clock’ would have been more to your liking and what you were experiencing.

Gay, I don’t know what to say!

Gay does it again, transporting me back to the days of my youth! I look forward to everything she writes!