Join a boat tour to the Farallon Islands, about 25 miles west of San Francisco, and you’ll likely see humpback and blue whales, gracefully arcing dolphins, sea lions, and thousands of seabirds. A bracing, salt-scented breeze scours these islands as the squawks of gulls, cormorants, and common murres create an outdoor symphony. Uninhabited by humans, the 3,295-square-mile Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary is a poster child for healthy oceans, but beneath the surface, the planet’s marine conditions are far from ideal.

Once thought to be so vast as to be immune to human degradation, the oceans supply us with copious amounts of seafood, regulate global temperatures, absorb a tremendous amount of carbon, and serve as venues for both transportation and recreation. But now we know oceans are not too big to fail. The health and stability of the sea is threatened by an array of powerful forces: rapacious overfishing, plastics pollution, acidification, and rising temperatures.

These dramatic shifts in the oceans have largely happened since the middle of the 20th century, a blip in geologic time.

“Here’s the thing: The ocean comprises the great majority of our life-support system,” says renowned oceanographer Sylvia Earle, 82, the former chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and now a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. “It shapes climate and weather and holds the planet steady with respect to temperature. It’s where most of life on Earth exists; it’s where most of the oxygen is generated; it’s where a great amount of the carbon is captured. It’s one big system, and until recent decades, the oceans have been largely unaffected by us. Now we have evidence, clear evidence, of the cause-and-effect relationship of what we are doing. Now we know, maybe just in time to save us from ourselves. This is good news.”

On the other side of the country, 71-year-old Rip Cunningham has been fishing along the Eastern seaboard since he was 7 or 8. He recalls the remarkable abundance of striped bass and other species, a plenitude that wouldn’t last into his adult years. “In the 1970s, we went into a huge decline” for striped bass, Cunningham says. “Fishery managers put a moratorium in most every state along the Atlantic coast where there were migratory striped bass.” Some fishermen were outraged — this was considered very drastic action at the time.

But the fishing restrictions made a difference. By 2006, striped bass had reached levels that “for 50 years we hadn’t really seen,” Cunningham says. “Striped bass essentially became the crown jewel of fisheries-management success.”

New England’s iconic fish is the Gulf of Maine codfish, he says. This is not a success story: The codfish population is down to 3 to 4 percent of its virgin stock. “Some say it’s environmental impact; the other end of the spectrum would say it’s all a product of long-term, chronic overfishing. My opinion: It’s both,” he says. “It was a fish that was very important to a lot of communities on the New England coast, and it’s essentially gone. There are some people who believe it can be brought back, and maybe it can.”

Today, it takes more than restricting fishing to bring a species back from the brink of extinction. Environmental factors, such as rising ocean -temperature and acidification, are affecting marine species in ways we’re just beginning to understand. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than any place along the coast of the continental United States, Cunningham says. “We don’t know what that ultimately means to the fish out there. We know it’s impacting plankton production; we know it’s impacting the shellfish industry. What that might ultimately do to the second most iconic species up here, the Maine lobster — the jury is out on that.”

In late August, in response to the Trump administration’s indication that it would seek to reduce the size of some national monuments, including protected ocean areas, U.S. Rep. Jared Huffman called a public hearing in Sausalito, a coastal town just north of San Francisco. Opening the hearing, Huffman noted that protecting special marine areas has never before been a partisan issue. “President George W. Bush designated our first four National Marine Monuments. No president has ever attempted to revoke a predecessor’s national monument designation.”

Representing a district with more than 500 miles of coastline — California’s second congressional district stretches from the Golden Gate Bridge to the Oregon border — Huffman has become an expert on marine policy. “These underwater parks provide many benefits,” he said at the hearing. “They help fish populations where the fish can actually grow large enough to reproduce, not only benefiting ocean ecosytems but also global fishing communities like the ones that I represent on the North Coast.”

Fishermen are especially concerned about proposals for opening new areas to oil drilling along the West Coast, says Noah Oppenheim, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations. Speaking at the hearing, he said oil and gas drilling inevitably causes oil spills that kill fish. He had one message for the more than 500 people who gathered at Sausalito’s Bay Institute: “Keep oil in the ground; keep it out of our ocean; keep it out of our marine sanctuaries.”

Perhaps the most heartfelt statement at the hearing came from an ordinary citizen who has long worked for ocean preservation, Rachel Binah of Little River, a seaside village near Mendocino: “Our emotional connection to the ocean is often ignored by those who would industrialize it. We are drawn to protect it because it is beautiful and because it inspires awe. The beauty and magnificence, our universal appreciation, fills a spiritual need for personal renewal and creativity.”

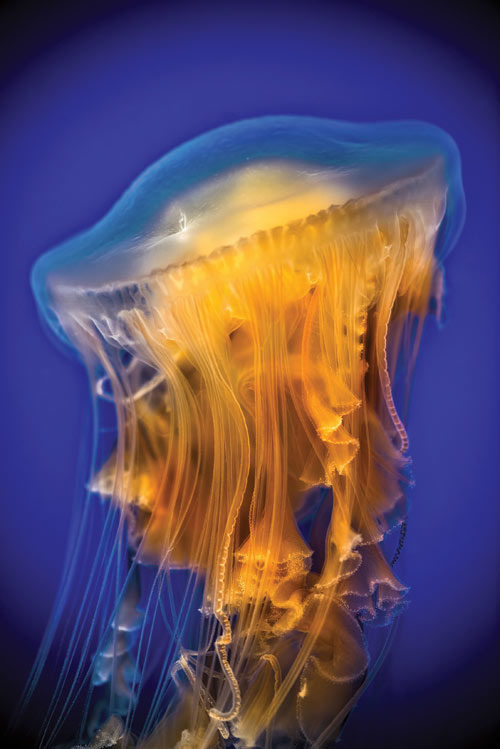

The creators of the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which re-defined the role of aquariums, recognize that healthy oceans can be a source of spiritual renewal. At first glance, the aquarium appears to celebrate fish (and other sea creatures) as art. As visitors enter the Open Sea exhibit, hundreds of glittering silver Pacific sardines race around a circular tank near the ceiling as ethereal music plays. Nearby are orange lion’s mane jellies (not called “jellyfish” because they’re not fish) and bioluminescent jellies that create their own colorful light.

The aquarium aims to let visitors know how they can help preserve the ocean by changing personal habits ranging from what we eat to how much plastic we use and how we dispose of it. The goal is to explain ocean environments and see how species live in harmony, says Margaret Spring, Monterey Bay Aquarium’s chief conservation officer. “So rather than a tank with one animal in it, you walk into a room and see the kelp forest, the cathedral of the ocean, and animals that live within the kelp. The idea is to help the general public learn to love the ocean like scientists do.”

To that end, a key part of the aquarium is outdoors. Its back deck is equipped with binoculars and spotting scopes trained on the wildlife in the bay. Visitors almost always spot sea otters swimming on their backs; those who are lucky may see dolphins and whales. Aquarium officials call Monterey Bay “our best exhibit.”

Program Engagement Manager Ryan Bigelow says the aquarium grew out of a desire to “open up the ocean, to show that natural beauty to our guests.” Without getting political, Monterey Bay Aquarium explains some of the problems facing the ocean, such as the plastic bags swallowed by fish or seabirds, often killing them.

An early exhibition discussed overfishing, which led aquarium visitors to ask: What should I eat? This sparked the aquarium’s Seafood Watch program, which includes a downloadable chart and smartphone app that sort fish choices into three categories: Best Choices (green), Good Alternatives (yellow), and Avoid (red). Best choices are “well managed and caught or farmed in ways that cause little harm to habitats or other wildlife,” according to the guide.

Monterey Bay Aquarium works with influencers ranging from institutional food services like Aramark to individual chefs who broker accords to protect species on the brink of extinction, such as the Pacific bluefin tuna, which is down to 2.6 percent of its historic numbers. Yet Spring was optimistic that the bluefin fishery “is fully capable of being recovered if we could just stop” taking so many fish. “They are fishing in the spawning areas; you’ve got to let them get bigger. The math isn’t working here. I would just say, don’t eat Pacific bluefin tuna. Don’t do it.”

In September 2017, when it was announced that Pacific nations had agreed to restore populations of bluefin tuna to sustainable levels, Spring called it a “historic moment” for the survival of the species. “If it is implemented appropriately, it will recover the population” of bluefin tuna to 20 percent of historic populations by 2034.

Fish is the last widely available wild protein — we don’t eat wild chickens or pigs or beef for the most part — and it’s efforts like the bluefin tuna accord that could sustain fisheries for many generations.

Asked if we’re in the era of the last wild fish for human consumption, Spring cites cause for hope: “That’s up to us. We’ve driven the ocean to the brink, but we can bring it back.” Sunfish take a long time to grow and mature, “so if everyone is eating those, yes they will disappear,” she says. “But there are other fish, like mahi mahi, which reproduce quite quickly, and they’re delicious.”

Farmed fish and shellfish are inevitably going to be part of the equation — and that’s not necessarily a bad thing, Bigelow says. At least 50 percent of the fish Americans eat is farmed. “The public overall has a very negative image of what farmed seafood is,” he adds, explaining that while some of it is “very, very red,” many fish farms are well-managed. “So if there’s a good farmed seafood story, we’ll tell it.”

The idea that “we’re going to feed ourselves solely with wild seafood, that’s never going to happen,” Bigelow adds. “We have to have farmed products, and if that’s the case, then we have to do it well. If you needed a panacea, we could just farm mussels and clams. You could provide all the protein for the world in a very small area with clams.”

Bigelow explains that mussels and clams can be cultivated in large numbers relatively easily because they don’t need feed, and “everything that we think about farmed fish overcrowding, they love.”

Limiting the catch of wild fish raises the question: What about the people around the world who depend on fish for sustenance? “Most of the fish that have been taken out of the ocean have not gone to poor populations,” says David Helvarg, executive director of Blue Frontier, an ocean advocacy group. “High-tech fishing fleets have stripped coastal waters from poor countries in order to provide a constant supply to the supermarket and white-linen-tablecloth restaurants in Europe, North America, and Japan, and increasingly China.”

But sometimes the little guys fight back — and win. “A few years ago, Senegal took away fishing permits from foreign trawlers, and within six months, local fishermen were catching levels of fish they hadn’t seen in a generation,” Helvarg says. “And after Indonesia’s navy helped banish almost 400 pirate vessels, hundreds of thousands of local Indonesian fishermen are seeing a recovery of their livelihood.”

Yet the overall recovery of oceans depends on forces beyond the seas. Helvarg says he’s “more frustrated than despairing with the ongoing disasters on our blue planet because we know what the solutions are. If you stop killing fish, they tend to grow back. If you stop producing 100 million metric tons of throw-away plastic every year, then you don’t face huge plastic pollution of our oceans.”

Another issue is that ocean acidification threatens shellfish, says Helvarg, author of 50 Ways to Save the Ocean: “I love oysters, raw oysters; they are mostly grown [farmed] now. But those who are growing oysters are facing problems due to acidification. As the ocean becomes more acidic, it eats away the shells.”

With the evidence piling up about ocean stability reaching a tipping point, we haven’t taken more decisive action because “the problem with environmental stories is they don’t break, they ooze,” Helvarg says, explaining, for example, that the full impact of carbon emissions on oceans won’t be felt for many years. “The trend lines are still challenging, but at least we recognize what the solutions are, and now we have to start working seriously to build the resilience for our coasts and oceans.”

Putting the seriousness of the issue in perspective, Sylvia Earle says, “It’s not just a matter of no longer getting to dine on bluefin tuna. If humans push the ocean past the point of no return, we could go down with the ship. Our life-support system is at risk.”

When humans act responsibly, Helvarg says, oceans tend to rebound. In the 19th century, whalers started killing elephant seals for their oil. “By 1896, there were an estimated 20 to 100 elephant seals left” along the Pacific coast, Helvarg says. “In the 1960s and ’70s, we changed our attitudes and created the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Clean Water Act, and we protected offshore breeding islands in the Channel Islands. In 1990, the first elephant seal hauled up on the beach near San Clemente, the first breeding pair was there in 1992, and last year 27,000 returned just to that one beach.

“When we do the right things, life comes back.”

The March for the Ocean will be June 9, 2018, in Washington D.C., and in cities across the country. For more info, see www.marchforocean.com.

Michael Shapiro is author of A Sense of Place and writes for National Geographic Traveler, Hemispheres, and The Washington Post. More at michaelshapiro.net.

This article is featured in the January/February 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The oceans are the life force for all the crucial inhabitants that live in it, and can no longer float along adrift in a ‘sea’ of bureaucracy, greed and indifference. It’s a matter where doing the right thing MUST override everything else, starting with reigning in the most destructive factor, humans, that have brought us to the edge of yet another disastrous cliff. In turn it will also take (and be) humans that will save it, if it is to be saved.