This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

Originally published January 28, 1967.

Spc. 4/c Jack P. Smith was a supply clerk in the 1st Air Cavalry Division in South Vietnam. Smith’s company — Charlie Company of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry (Regiment) — had never been in action, and Smith, who was 20 years old, had come to believe that it never would. “We thought we were a sham,” Smith recalls today. “We dug and walked and looked for an enemy who was never there.”

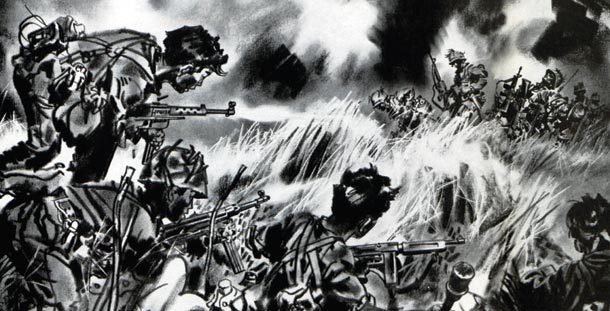

In November 1965, units of the 7th Cavalry began to make the first American penetration in force of a communist stronghold near the Cambodian border. On November 15, Smith’s battalion was ordered in to help the 1st Battalion, which was meeting strong resistance. This was the beginning of the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, the first pitched battle fought by American soldiers in the war for Vietnam, and the bloodiest engagement of the long and divisive struggle.

After a day of marching into the jungle, Smith and the 500 other men of the 2nd Battalion came upon a clearing, known on the maps as X‑ray, where the 1st Battalion was fighting. The names of the soldiers have been changed, but in all other respects, this is what happened.

The 1st Battalion had been fighting continuously for three or four days, and I had never seen such filthy troops. Some of them had blood on their faces from scratches and from other guys’ wounds. Some had long rips in their clothing where shrapnel and bullets had missed them. They all had that look of shock. They said little, just looked around with darting, nervous eyes.

Whenever I heard a shell coming close, I’d duck, but they’d keep standing. After three days of constant bombardment, you get so you can tell from the sound how close a shell is going to land within 50 to 75 feet. There were some wounded lying around, bandaged up with filthy shirts and bandages, smoking cigarettes or lying in a coma with plasma bottles hanging above their stretchers.

Late that morning, the Cong made a charge. About 100 of them jumped up and made for our lines, and all hell broke loose. The people in that sector opened up with everything they had. Then a couple of our Skyraiders came in. One of them dropped a lot of stuff that shimmered in the sun like green confetti. It looked like a ticker-tape parade, but when the things hit the ground, the little pieces exploded. They were anti-personnel charges. Every one of the gooks was killed. Another group on the other side almost made it to the lines. There weren’t enough GIs there, and they couldn’t shoot them down fast enough. A plane dropped some napalm bombs just in front of the line. I couldn’t see the gooks. But I could hear them scream as they burned. A hundred men dead, just like that.

My company, Charlie Company, took over its sector of the battalion perimeter and started to dig in. At three o’clock another attack came, but it never amounted to anything. I didn’t get any sleep that night. There was continuous firing from one until four, and it was as bright as day with the flares lighting up the sky.

The next morning, the order came for us to move out. I guess our commanders felt the battle was over. The three battalions of PAVN (People’s Army of Vietnam — the North Vietnamese) were destroyed. There must have been about 1,000 rotting bodies out there, starting about 20 feet from us and surrounding the giant circle of foxholes. As we left the perimeter, we walked by them. Some of them had been lying out there for four days. There are more ants in Vietnam than in any place I have ever seen.

We were being withdrawn to Landing Zone Albany, some 6 miles away, where we were to be picked up by helicopter. About noon the column stopped and everybody flopped on the ground. It turned out that our reconnaissance platoon had come upon four sleeping PAVN who had claimed they were deserters. They said that there were three or four snipers in the trees up ahead — friends of theirs who did not want to surrender.

The head of the column formed by our battalion was already in the landing zone, which was actually only 30 yards to our left. But our company was still in the woods and elephant grass. I dropped my gear and my ax, which was standard equipment for supply clerks like me. We used them to cut down trees to help make landing zones for our helicopters. The day had grown very hot. I was about one-quarter through a smoke when a few shots cracked at the front of the column.

I flipped my cigarette butt, lay down, and grabbed my M-16. The fire in front was still growing. Then a few shots were fired right behind me. They seemed to come from the trees. There was firing all over the place now, and I was getting scared. A bullet hit the dirt a foot to my side, and some started whistling over my head.

This wasn’t the three or four snipers we had been warned about. There were over 100 North Vietnamese snipers tied in the trees above us — so we learned later — way above us, in the top branches. The firing kept increasing.

Our executive officer (XO) jumped up and said, “Follow me, and let’s get the hell out of here.” I followed him, along with the rest of the headquarters section and the 1st Platoon. We crouched and ran to the right toward what we thought was the landing zone. But it was only a small clearing — the L.Z. was to our left. We were running deeper into the ambush.

The fire was still increasing. We were all crouched as low as possible, but still keeping up a steady trot, looking from side to side. I glanced back at Richards, one of the company’s radio operators. Just as I looked back, he moaned softly and fell to the ground. I knelt down and looked at him, and he shuddered and started to gurgle deep in his stomach. His eyes and tongue popped out, and he died. He had a hole straight through his heart.

I had been screaming for a medic. I stopped. I looked up. Everyone had stopped. All of a sudden all the snipers opened up with automatic weapons. There were PAVN with machine guns hidden behind every anthill. The noise was deafening.

Then the men started dropping. It was unbelievable. I knelt there staring as at least 20 men dropped within a few seconds. I still had not recovered from the shock of seeing Richards killed, but the jolt of seeing men die so quickly brought me back to life. I hit the dirt fast. The XO was to my left, and Wallace was to my right, with Burroughs to his right. We were touching each other lying there in the tall elephant grass.

Men all around me were screaming. The fire was now a continuous roar. We were even being fired at by our own guys. No one knew where the fire was coming from, and so the men were shooting everywhere. Some were in shock and were blazing away at everything they saw or imagined they saw.

The XO let out a low moan, and his head sank. I felt a flash of panic. I had been assuming that he would get us out of this. Enlisted men may scoff at officers back in the billets, but when the fighting begins, the men automatically become very dependent upon them. Now I felt terribly alone.

The XO had been hit in the small of the back. I ripped off his shirt and there it was: a groove to the right of his spine. The bullet was still in there. He was in a great deal of pain, so a rifleman named Wilson and I removed his gear as best we could, and I bandaged his wound. It was not bleeding much on the outside, but he was very close to passing out.

Just then Wallace let out a “Huh!” A bullet had creased his upper arm and entered his side. He was bleeding in spurts. I ripped away his shirt with my knife and did him up. Then the XO screamed: A bullet had gone through his boot, taking all his toes with it. He was in agony and crying. Wallace was swearing and in shock. I was crying and holding on to the XO’s hand to keep from going crazy.

The grass in front of Wallace’s head began to fall as if a lawnmower were passing. It was a machine gun, and I could see the vague outline of the Cong’s head behind the foot or so of elephant grass. The noise of firing from all directions was so great that I couldn’t even hear a machine gun being fired three feet in front of me and one foot above my head.

As if in a dream, I picked up my rifle, put it on automatic, pushed the barrel into the Cong’s face and pulled the trigger. I saw his face disappear. I guess I blew his head off, but I never saw his body and did not look for it.

Wallace screamed. I had fired the burst pretty close to his ear, but I didn’t hit him. Bullets by the thousands were coming from the trees, from the L.Z., from the very ground, it seemed. There was a huge thump nearby. Burroughs rolled over and started a scream, though it sounded more like a growl. He had been lying on his side when a grenade went off about three or four feet from him. He looked as though someone had poured red paint over him from head to toe.

After that everything began getting hazy. I lay there for several minutes, and I think I was beginning to go into shock. I don’t remember much.

The amazing thing about all this was that from the time Richards was killed to the time Burroughs was hit, only a minute or two had elapsed. Hundreds of men had been hit all around us, and the sound of men screaming was almost as loud as the firing.

The XO was going fast. He told me his wife’s name was Carol. He told me that if he didn’t make it, I was to write her and tell her that he loved her. Then he somehow managed to crawl away, saying that he was going to organize the troops. It was his positive decision to do something that reinforced my own will to go on.

Then our artillery and air strikes started to come in. They saved our lives. Just before they started, I could hear North Vietnamese voices on our right. The PAVN battalion was moving in on us, into the woods. The Skyraiders were dropping napalm bombs a hundred feet in front of me on a PAVN machine-gun complex. I felt the hot blast and saw the elephant grass curling ahead of me. The victims were screaming — some of them were our own men who were trapped outside the wood line.

At an altitude of 200 feet, it’s difficult to distinguish one soldier from another. It’s unfortunate and horrible, but most of the battalion’s casualties in the first hour or so were from our own men, firing at everything in sight.

No matter what you did, you got hit. The snipers in the trees just waited for someone to move, then shot him. I could hear the North Vietnamese entering the woods from our right. They were creeping along, babbling and arguing among themselves, calling to each other when they found a live GI. Then they shot him.

I decided that it was time to move. I crawled off to my left a few feet, to where Sgt. Moore and Thompson were lying. Sgt. Moore had been hit in the chest three times. He was in pain and sinking fast. Thompson was hit only lightly in the leg. I asked the sergeant to hold my hand. He must have known then that he was dying, but he managed to assure me that everything would be all right.

I knew there wasn’t much chance of that. This was a massacre, and I was one of a handful not yet wounded. All around me, those who were not already dead were dying or severely wounded, most of them hit several times. I must have been talking a lot, but I have no idea what I was saying. I think it was, “Oh God, Oh God, Oh God,” over and over. Then I would cry. To get closer to the ground, I had dumped my gear, including the ax I had been carrying, and I had lost my rifle, but that was no problem. There were weapons of every kind lying everywhere.

Sgt. Moore asked me if I thought he would make it. I squeezed his hand and told him sure. He said that he was in a lot of pain, and every now and then he would scream. He was obviously bleeding internally quite a bit. I was sure that he would die before the night. I had seen his wife and four kids at Fort Benning. He had made it through World War II and Korea, but this little war had got him.

I found a hand grenade and put it next to me. Then I pulled out my first-aid pack and opened it. I still was not wounded, but I knew I would be soon.

At that instant, I heard a babble of Vietnamese voices close by. They sounded like little children, cruel children. The sound of those voices, of the enemy that close, was the most frightening thing I have ever experienced. Combat creates a mindless fear, but this was worse, naked panic.

A small group of PAVN was rapidly approaching. There was a heavy rustling of elephant grass and a constant babbling of high-pitched voices. I told Sgt. Moore to shut up and play dead. I was thinking of using my grenade, but I was scared that it wouldn’t get them all, and that they were so close that I would blow myself up too.

My mind was made up for me, because all of a sudden, they were there. I stuck the grenade under my belly so that even if I was hit the grenade would not go off too easily, and if it did go off I would not feel pain. I willed myself to stop shaking, and I stopped breathing. There were about 10 or 12 of them, I figure. They took me for dead, thank God. They lay down all around me, still babbling.

One of them lay down on top of me and started to set up his machine gun. He dropped his canister next to my side. His feet were by my head, and his head was between my feet. He was about six feet tall and pretty bony. He probably couldn’t feel me shaking because he was shaking so much himself.

I thought I was gone. I was trying like hell to act dead, however the hell one does that.

The Cong opened up on our mortar platoon, which was set up around a big tree nearby. The platoon returned the fire, killing about half of the Cong, and miraculously not hitting me. All of a sudden a dozen loud crumph sounds went off all around me. Assuming that all the GIs in front of them were dead, our mortar platoon had opened up with M-79 grenade launchers. The Cong jumped up off me, moaning with fear, and the other PAVN began to move around. They apparently knew the M-79. Then a second series of explosions went off, killing all the Cong as they got up to run. One grenade landed between Thompson’s head and Sgt. Moore’s chest. Sgt. Moore saved my life; he took most of the shrapnel in his side. A piece got me in the head.

It felt as if a white-hot sledge hammer had hit the right side of my face. Then something hot and stinging hit my left leg. I lost consciousness for a few seconds. I came out of it feeling intense pain in my leg and a numbness in my head. I didn’t dare feel my face: I thought the whole side of it had gone. Blood was pouring down my forehead and filling the hollow of my eyeglasses. It was also pouring out of my mouth. I slapped a bandage on the side of my face and tied it around my head. I was numbed, but I suddenly felt better. It had happened, and I was still alive.

I decided it was time to get out. None of my buddies appeared able to move. The Cong obviously had the mortar platoon pegged, and they would try to overrun it again. I was going to be right in their path. I crawled over Sgt. Moore, who had half his chest gone, and Thompson, who had no head left. Wilson, who had helped me with the XO, had been hit badly, but I couldn’t tell where. All that moved was his eyes. He asked me for some water. I gave him one of the two canteens I had scrounged. I still had the hand grenade.

I crawled over many bodies, all still. The 1st Platoon just didn’t exist anymore. One guy had his arm blown off. There was only some shredded skin and a piece of bone sticking out of his sleeve. The sight didn’t bother me anymore. The artillery was still keeping up a steady barrage, as were the planes, and the noise was as loud as ever, but I didn’t hear it anymore. It was a miracle I didn’t get shot by the snipers in the trees while I was moving.

came across Sgt. Barker, who stuck a .45 in my face. He thought I was a Cong and almost shot me. Apparently I was now close to the mortar platoon. Many other wounded men had crawled over there, including the medic Novak, who had run out of supplies after five minutes. Barker was hit in the legs. Caine was hurt badly too. There were many others, all in bad shape. I lay there with the hand grenade under me, praying. The Cong made several more attacks, which the mortar platoon fought off with 79s.

The Cong figured out that the mortar platoon was right by that tree, and three of their machine-gun crews crawled up and started to blaze away. It had taken them only a minute or so to find exactly where the platoon was; it took them half a minute to wipe it out. When they opened up, I heard a guy close by scream, then another, and another. Every few seconds someone would scream. Some got hit several times. In 30 seconds, the platoon was virtually nonexistent. I heard Lt. Sheldon scream three times, but he lived. I think only five or six guys from the platoon were alive the next day.

It also seemed that most of them were hit in the belly. I don’t know why, but when a man is hit in the belly, he screams an unearthly scream. Something you cannot imagine; you actually have to hear it. When a man is hit in the chest or the belly, he keeps on screaming, sometimes until he dies. I just lay there, numb, listening to the bullets whining over me and the 15 or 20 men close to me screaming and screaming and screaming. They didn’t ever stop for breath. They kept on until they were hoarse, then they would bleed through their mouths and pass out. They would wake up and start screaming again. Then they would die.

I started crying. Sgt. Gale was lying near me. He had been hit badly in the stomach and was in great pain. He would lie very still for a while and then scream. He would scream for a doctor, then he would scream for a medic. He pleaded with anyone he saw to help him, for the love of God, to stop his pain or kill him. He would thrash around and scream some more, and then lie still for a while. He was bleeding a lot. Everyone was. No matter where you put your hand, the ground was sticky.

Sgt. Gale lay there for over six hours before he died. No one had any medical supplies, no one could move, and no one would shoot him.

Several guys shot themselves that day. Schiff, although he was not wounded, completely lost his head and killed himself with his own grenade. Two other men, both wounded, shot themselves with .45s rather than let themselves be captured alive by the gooks. No one will ever know how many chose that way out, since all the dead had been hit over and over again.

All afternoon we could hear the PAVN, a whole battalion, running through the grass and trees. Hundreds of GIs were scattered on the ground like salt. Sprinkled among them like pepper were the wounded and dead Cong. The GIs who were wounded badly were screaming for medics. The Cong soon found them and killed them.

All afternoon there was smoke, artillery, screaming, moaning, fear, bullets, blood, and little yellow men running around screeching with glee when they found one of us alive, or screaming and moaning with fear when they ran into a grenade or a bullet. I suppose that all massacres in wars are a bloody mess, but this one seemed bloodier to me because I was caught in it.

About dusk a few helicopters tried landing in the L.Z., about 40 yards over to the left, but whenever one came within 100 feet of the ground, so many machine guns would open up on him that it sounded like a training company at a machine-gun range.

At dusk the North Vietnamese started to mortar us. Some of the mortars they used were ours that they had captured. Suddenly the ground behind me lifted up, and there was a tremendous noise. I knew something big had gone off right behind me. At the same time I felt something white-hot go into my right thigh. I started screaming and screaming. The pain was terrible. Then I said, “My legs, God, my legs,” over and over.

Still screaming, I ripped the bandage off my face and tied it around my thigh. It didn’t fit, so I held it as tight as I could with my fingers. I could feel the blood pouring out of the hole. I cried and moaned. It was hurting unbelievably. The realization came to me now, for the first time, that I was not going to live.

With hardly any light left, the Cong decided to infiltrate the woods thoroughly. They were running everywhere. There were no groupings of Americans left in the woods, just a GI here and there. The planes had left, but the artillery kept up the barrage.

Then the flares started up. As long as there was some light, the Cong wouldn’t try an all-out attack. I was lying there in a stupor, thirsty. God, I was thirsty. I had been all afternoon with no water, sweating like hell.

I decided to chance a cigarette. All my original equipment and weapons were gone, but somehow my cigarettes were still with me. The ends were bloody. I tore off the ends and lit the middle part of a cigarette.

Cupping it and blowing away the smoke, I managed to escape detection. I knew I was a fool. But at this stage I didn’t really give a damn. By now the small-arms fire had stopped almost entirely. The woods were left to the dead, the wounded, and the artillery barrage.

At nightfall I had crawled across to where Barker, Caine, and a few others were lying. I didn’t say a word. I just lay there on my back, listening to the swishing of grass, the sporadic fire and the constant artillery, which was coming pretty close. For over six hours now, shells had been landing within a hundred yards of me.

I didn’t move, because I couldn’t. Reaching around, I found a canteen of water. The guy who had taken the last drink from it must have been hit in the face, because the water was about one third blood. I didn’t mind. I passed it around.

About an hour after dark there was a heavy concentration of small-arms fire all around us. It lasted about five minutes. It was repeated at intervals all night long. Battalion Hq. was firing a protective fire, and we were right in the path of the bullets. Some of our men were getting hit by the rounds ricocheting through the woods.

I lay there shivering. At night in the highlands the temperature goes down to 50 or so. About midnight I heard the grass swishing. It was men, and a lot of them too. I took my hand grenade and straightened out the pin. I thought to myself that now at last they were going to come and kill all the wounded that were left. I was sure I was going to die, and I really did not care anymore. I did not want them to take me alive. The others around me were either unconscious or didn’t care. They were just lying there. I think most of them had quietly died in the last few hours. I know one — I did not recognize him — wanted to be alone to die. When he felt himself going, he crawled over me (I don’t know how), and a few minutes later I heard him gurgle and, I guess, die.

Then suddenly I realized that the men were making little whistling noises.

Maybe these weren’t the Cong. A few seconds later, a patrol of GIs came into view, about 15 guys in line, looking for wounded.

Everyone started pawing toward them and crying. It turned me into a babbling idiot. I grabbed one of the guys and wouldn’t let go. They had four stretchers with them, and they took the four worst wounded and all the walking wounded, about 10 or so, from the company. I was desperate, and I told the leader I could walk, but when Peters helped me to my feet, I passed out cold.

When I regained consciousness, they had gone, but their medic was left behind, a few feet from me, by a tree. He hadn’t seen me, and had already used his meager supply of bandages on those guys who had crawled up around the tree. His patrol said they would be back in a few hours.

I clung to the hope, but I knew damn well they weren’t coming back. Novak, who was one of the walking wounded, had left me his .45. I lost one of the magazines, and the only other one had only three bullets in it. I still had the hand grenade.

I crawled up to the tree. There were about eight guys there, all badly wounded. Lt. Sheldon was there, and he had the only operational radio left in the company. I couldn’t hear him, but he was talking to the company commander, who had gotten separated from us. Lt. Sheldon had been wounded in the thighbone, the kneecap, and the ankle.

Some time after midnight, in my half-conscious stupor, I heard a lot of rustling on both sides of the tree. I nudged the lieutenant, and then he heard it too. Slowly, everyone who could move started to arm himself. I don’t know who it was — it might even have been me — but someone made a noise with a weapon.

The swishing noise stopped immediately. Ten yards or so from us an excited babbling started. The gooks must have thought they had run into a pocket of resistance around the tree. Thank God, they didn’t dare rush us, because we wouldn’t have lasted a second. Half of us were too weak to even cock our weapons. As a matter of fact, there were a couple who did not have fingers to cock with.

Then a clanking noise started: They were setting up a machine gun right next to us. I noticed that some artillery shells were landing close now, and every few seconds they seemed to creep closer to us, until one of the Cong screamed. Then the babbling grew louder. I heard the lieutenant on the radio; he was requesting a salvo to bracket us. A few seconds later there was a loud whistling in the air and shells were landing all around us, again and again. I heard the Cong run away. They left some of their wounded a couple of yards from us, moaning and screaming, but they died within a few minutes.

Every half hour or so the artillery would start all over again. It was a long night. Every time, the shells came so close to our position that we could hear the shrapnel striking the tree a foot or so above our heads, and could hear other pieces humming by just inches over us.

All night long the Cong had been moving around killing the wounded. Every few minutes I heard some guy start screaming, “No, no, no, please,” and then a burst of bullets. When they found a guy who was wounded, they’d make an awful racket. They’d yell for their buddies and babble awhile, then turn the poor devil over and listen to him while they stuck a barrel in his face and squeezed.

About an hour before dawn the artillery stopped, except for an occasional shell. But the small-arms firing started up again, just as heavy as it had been the previous afternoon. The GIs about a mile away were advancing and clearing the ground and trees of Cong (and a few Americans too). The snipers, all around the trees and in them, started firing back.

When a bullet is fired at you, it makes a distinctive, sharp cracking sound. The firing by the GIs was all cracks. I could hear thuds all around me from the bullets. I thought I was all dried out from bleeding and sweating, but now I started sweating all over again. I thought, How futile it would be to die now from an American bullet. I just barely managed to keep myself from screaming out loud. I think some guy near me got hit. He let out a long sigh and gurgled.

Soon the sky began to turn red and orange. There was complete silence everywhere now. Not even the birds started their usual singing. As the sun was coming up, everyone expected a human-wave charge by the PAVN, and then a total massacre. We didn’t know that the few Cong left from the battle had pulled out just before dawn, leaving only their wounded and a few suicide squads behind.

When the light grew stronger, I could see all around me. The scene might have been the devil’s butcher shop. There were dead men all around the tree. I found that the dead body I had been resting my head on was that of Burgess, one of my buddies. I could hardly recognize him. He was a professional saxophone player with only two weeks left in the Army.

Right in front of me was Sgt. Delaney with both his legs blown off. I had been staring at him all night without knowing who he was. His eyes were open and covered with dirt. Sgt. Gale was dead too. Most of the dead were unrecognizable and were beginning to stink. There was blood and mess all over the place.

Half a dozen of the wounded were alive. Lord, who was full of shrapnel; Lt. Sheldon, with several bullet wounds; Morris, shot in the legs and arm; Sloan, with his fingers shot off; Olson, with his leg shot up and hands mutilated; and some guy from another company who was holding his guts from falling out.

Dead Cong were hanging out of the trees everywhere. The Americans had fired bursts that had blown some snipers right out of the trees. But these guys, they were just hanging and dangling there in silence.

We were all sprawled out in various stages of unconsciousness. My wounds had started bleeding again, and the heat was getting bad. The ants were getting to my legs.

Lt. Sheldon passed out, so I took over the radio. That whole morning is rather blurred in my memory. I remember talking for a long time with someone from Battalion Hq. He kept telling me to keep calm, that they would have the medics and helicopters in there in no time. He asked me about the condition of the wounded. I told him that the few who were still alive wouldn’t last long. I listened for a long time on the radio to chitchat between medevac pilots, Air Force jet pilots, and Battalion Hq. Every now and then I would call up and ask when they were going to pick us up. I’m sure I said a lot of other things, but I don’t remember much about it.

I just couldn’t understand at first why the medevacs didn’t come in and get us. Finally I heard on the radio that they wouldn’t land because no one knew whether or not the area was secure. Some of the wounded guys were beginning to babble. It seemed like hours before anything happened.

Then a small Air Force spotter plane was buzzing overhead. It dropped a couple of flares in the L.Z. nearby, marking the spot for an airstrike. I thought, My God, the strike is going to land on top of us. I got through to the old man — the company commander — who was up ahead, and he said that it wouldn’t come near us and for us not to worry. But I worried, and it landed pretty damn close.

There was silence for a while, then they started hitting the L.Z. with artillery, a lot of it. This lasted for a half hour or so, and then the small arms started again, whistling and buzzing through the woods. I was terrified. I thought, My Lord, is this never going to end? If we’re going to die, let’s get it over with.

Finally the firing stopped, and there was a ghastly silence. Then the old man got on the radio again and talked to me. He called in a helicopter and told me to guide it over our area. I talked to the pilot, directing him, until he said he could see me. Some of the wounded saw the chopper and started yelling, “Medic! Medic!” Others were moaning feebly and struggling to wave at the chopper.

The old man saw the helicopter circling and said he was coming to help us. He asked me to throw a smoke grenade, which I pulled off Lt. Sheldon’s gear. It went off, and the old man saw it, because soon after that I heard the guys coming. They were shooting as they walked along. I screamed into the radio, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot,” but they called back and said they were just shooting PAVN.

Then I saw them: The 1st sergeant, our captain, and the two radio operators. The captain came up to me and asked me how I was.

I said to him: “Sorry, sir, I lost my —— ax.”

He said, “Don’t worry, Smitty, we’ll get you another one.”

The medics at the L.Z. cut off my boots and put bandages on me. My wounds were in pretty bad shape. You know what happens when you take raw meat and throw it on the ground on a sunny day. We were out there for 24 hours, and Vietnam is nothing but one big anthill.

I was put in a medevac chopper and flown to Pleiku, where they changed dressings and stuck all sorts of tubes in my arms. At Pleiku I saw Gruber briefly. He was a clerk in the battalion, and my Army buddy. We talked until they put me in the plane. I learned that Stern and Deschamps, close friends, had been found dead together, shot in the backs of their heads, executed by the Cong. Gruber had identified their bodies. Everyone was crying. Like most of the men in our battalion, I had lost all my Army friends.

I heard the casualty figures a few days later. The North Vietnamese unit had been wiped out — over 500 dead. Out of some 500 men in our battalion alone, about 150 had been killed, and only 84 returned to base camp a few days later. In my company, which was right in the middle of the ambush, we had 93 percent casualties — one half dead, one half wounded. Almost all the wounded were crippled for life. The company, in fact, was very nearly annihilated.

Our unit is part of the 7th Cavalry — Custer’s old unit. That day in the Ia Drang Valley, history repeated itself.

After a week in and out of field hospitals, I ended up at Camp Zama in Japan. They have operated on me twice. They tell me that I’ll walk again, and that my legs are going to be fine. But no one can tell me when I will stop having nightmares.

Postscript: Jack Smith did recover from his wounds and was sent back to his unit in Vietnam, where he served as a supply clerk from January to July 1966. He did not see any more action. He finished up his military career training recruits at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

—“Death in the Ia Drang Valley,” January 28, 1967

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now