This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

This article and other features about America in Vietnam can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Heroes of Vietnam. This edition can be ordered here.

—Originally published February 8, 1969—

One way or another they all come home. After a year if they are lucky; sooner if they are not. They come by troop plane, jubilant, crying, exhausted, unable to believe it is over and they are safe. Or by hospital plane, with the litters stacked three high on either side and the nurses moving softly through the pain. Or by cargo plane, in a closed aluminum box. Nearly half a million men came home from Vietnam last year. Thirty thousand of these came back wounded; thirteen thousand came back dead. This is the story of three. It is also a story of the nation that sent them.

Editor’s note: “Three Who Came Home” is a true story. However, the names of Jerry Spitzer and some other persons in this vignette are not real, and some biographical and geographical details have been changed. Nothing has been changed concerning the people or places in the other two parts of the story.

Part One: Jerry Spitzer

There here were eight NO SMOKING signs on the walls. Then there was a sign that said: “GOOD LUCK. Gentlemen, you can be proud of your honest and faithful service to your country. Rest assured that your service has been recognized and is appreciated by your fellow Americans … Good-bye, and good luck.”

Jerry Spitzer finished filling out his forms: DD Form 214, DD Form 1407, DD Form 1580, DA Form 2376 …

“… Now if you will move through the doorway to your left and across the hall, and form a single line at the pay window …”

The hallway smelled of mothballs. Jerry Spitzer, of Marion, New Castle, Shelbyville, Seymour, and Richmond, Indiana, was home from Vietnam and almost out of the Army. He stood in line and after a few minutes he could not smell the mothballs.

Jerry Spitzer was lucky. He had come back standing up.

In Vietnam, his job had been to ride in boats that went down narrow rivers. When the boat stopped, he would jump off and run into the jungle, looking for Viet Cong to kill. For three months he did not find any.

Still, he did not like his job; it scared him. He mentioned this to his company commander and he was transferred to a barge. The barge carried mortars. It was pushed down the rivers by a boat and left to spend the day. The men on the barge would fire the mortars into the jungle. At the end of the day, the boat would return and tow the barge back to camp. This was better than running into the jungle, but still it was not so good. For instance, when the Viet Cong attacked, there was no place to hide, and some of the men jumped into the river. Jerry Spitzer could not remember anyone who had jumped into the river and not drowned.

He spent seven months on the barge. He became a corporal. He wrote letters home: “I don’t know, Ma, me and President Johnson, we just don’t think alike, I guess.”

Comedian Mort Sahl was not going to be at the hungry i that night, as had been announced, but Jerry Spitzer did not care. He had never heard of Mort Sahl. He had never heard of the hungry i either, but when he had gotten into the cab, late that cloudy afternoon, after finally having escaped from the out-processing center at Oakland, Jerry Spitzer had asked the driver for a good place to kill five hours waiting for a plane. The driver, who was without imagination, took him to the hungry i.

And there Jerry Spitzer was sitting, as summer twilight came to San Francisco, at an empty bar in a dim, red room, with album covers on the walls and a girl who drew caricatures ($3 black and white; $6 color) sitting at a table in the back, filing her nails.

“Almost didn’t come home,” Jerry Spitzer was saying.

“Why not?”

“Almost got married.” He grinned beneath an unsuccessful moustache. “To a Vietnamese girl.” He reached for his wallet. The picture, of the two of them, had been taken from a distance and was not very clear.

“What’s her name?”

“Nga.”

He was going to marry her. “The only foreign girl I never touched.” But when he asked the Army if he could stay in Vietnam long enough to do it, they told him it was too late. He would have to go home as scheduled. “When did you ask them?”

“The day before I was supposed to come home.”

So Jerry Spitzer, 20 years old, thin, with a face that still had pimples on the chin, spent his final hours in Vietnam searching for a Vietnamese-English dictionary that would enable him to write to Nga and explain why they could not get married. He did not find one.

“Say, what’s that lady doin’? Is she drawin’ one a them characters?”

She was; for a banker in a gray suit and his date. The banker was in his late 40s. The date was younger, tall, and had good legs.

“I’d kind a like one. You know, kind a somethin’ to bring home.”

The woman was finished with the banker and his date. She showed them what she had done. They laughed, the banker paid her, and they went back to the bar. Jerry Spitzer lit a cigarette, coughed deep and hard, the way he had been coughing all afternoon, straightened the jacket of his uniform, and walked to the back of the room.

“Ma’am, I’d like you to draw me one a those.”

She motioned him into the chair.

“Have you just come back from Vietnam?”

“Last night. And I got out this afternoon. I’m not in the Army no more.”

“I see.”

She worked quickly, with big sweeping strokes of a charcoal pencil. She drew a profile, making his nose enormous. Then she drew lines to indicate that his head was spinning to the right, and in the right corner she drew a cartoon blonde. At the top she wrote a caption: “I knew there was something to come home for.”

She tore it off the pad and gave it to him. He handed her three dollars and stared at the picture. The way she had drawn his uniform and the way she had his head spinning made him look like a waiter slipping on a grease spot in a cheap restaurant.

“What’s your position on the war?”

“Pardon, ma’am?”

“Do you think we have any right to be there?”

“I don’t know, ma’am.”

“Oh, don’t tell me you don’t know. You’ve just been there. You must feel something about it. “

“I don’t know, ma’am, but all I know is I don’t see no point in gettin’ killed over a bunch a gooks.”

“Yet you went there and fought. You killed Vietnamese people who —”

“Wait a minute.” The banker in the gray suit was up from the bar.

He looked at the picture she had drawn. “This man didn’t start the war. He was sent there by his country, and he went and he did what he was told to do. And now he’s come home. Do you know what that means?”

“No.”

“Well, I want you to think about what it means. And then I want you to draw a new picture of this man, getting in there what he is and what he’s done and what it means that he’s come home. Go on. I’ll pay you for it. But draw something decent this time.”

She looked across the table at Jerry Spitzer.

“Would you mind posing a few more minutes?”

“No, ma’am.”

“All right.” She bent to her pencils and chalks. She made a stroke on the paper. She made another one in a different place. Then she reached up and tore the page off the pad and crumpled it on the floor.

She stared at the fresh paper a long time. Then she made a slow, tentative stroke.

It took 20 minutes to do the drawing. It was a three-quarters head and shoulders, with deep shadows in the face and strong lines and a power and sadness in the eyes. It was the finest Jerry Spitzer would ever look in his life.

“Just one more minute,” she said.

Jerry Spitzer nodded. He had been sitting perfectly still through it all, not even smoking, for the first time all day.

Karen LeVine began to write across the bottom of the picture: “Fortunate indeed is the hero home from this war — alive.” Then she took the picture from the pad very gently.

He stared at it and his head began to move up and down and he did not say anything.

“Beautiful,” the banker’s date said.

“That’s it,” the banker said. “That’s just what I meant.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” Spitzer said, “it’s a nice drawin’.”

The banker took a $10 bill from his wallet and put it on the table. “Thanks again.” He took the picture and handed it to Jerry Spitzer. “Here. Take this one home to your mother. This is one you can hang on your wall.”

How he met Artie and Danny and Carol was unclear. But there he was, talking to them, at a table in the back of the hungry i, and the three of them, Artie with gray hair and sideburns; Danny, with the big black moustache; and Carol, who was Artie’s girl, listening to Jerry Spitzer talk on and on about Indiana.

And Artie, who was getting a doctorate at Berkeley, and Danny, who was getting a doctorate at Columbia and was on vacation, and Carol, who taught school in New Haven, Connecticut, all fell in love with Jerry Spitzer.

“Listen,” Artie said, two hours later. “Stay here tonight. We can go over to Berkeley and go out for a while over there and then you can sleep at my place.”

Jerry Spitzer had a midnight plane. But the beer was working in him now and he thought about what there was at home: Betty, the girl he had tried to break up with by mail; the plant, where maybe he could get a job; the long, flat, thin roads of mid-America; the little jukebox bars and the hot summers and the winters when nothing moved, and the men who wore T-shirts in the factories, and his mother whose heart was weak — and he thought briefly about where he had been three days before. He looked across the table at crazy Artie with the sideburns and how come his hair was getting gray already, and Danny with that goddamn moustache, and Carol whom he couldn’t figure out because she didn’t look like a hippie but if he ever caught Betty in one of those skirts he’d kill her.

“Okay.”

So Jerry Spitzer, still in his new green uniform, with his caricatures under his arm, climbed into the back of Artie’s MG, with Danny huddled next to him, and Carol in the front, and Artie drove up the high hills and down them.

At intersections, when Artie would have to slow down, people would turn and stare. Jerry was standing straight up, saluting. Danny was playing a kazoo that had come from the pocket of his peacoat. It was Jerry’s motorcade and he was proud. Welcome home, Jerry, welcome home. Jerry waved to the people. Danny blew hard on the kazoo. Up the hills and down them. Home from Vietnam. Home to his grateful nation. Artie drove across the cold bridge into Berkeley.

Artie lived on the side of a hill near the football stadium. There were long flights of steps outdoors and then more inside to the third floor where Artie had a room. Artie opened a drawer in his desk and took out a pouch and began to roll cigarettes in brown paper.

“This is good stuff, Jerry, better than what you got over there.”

“I hope so, because over there that stuff didn’t do nothin’ for me.”

Then Artie took out a jug of red California wine. Sweet smoke filled the room. And music. Jerry Spitzer took off his new green uniform and folded it neatly over the edge of a chair. He put on khaki pants and a sweatshirt. He sat on the edge of a bed. The music was loud. Artie rolled more cigarettes. The jug was passed. Danny was in a corner, playing bongo drums.

Carol was staring out a window. She had stopped talking too. The lights of San Francisco were out there.

Artie sat backward in a chair, staring at the floor. The music got louder. Jerry Spitzer sucked the smoke deep into his lungs. Three days before, he had been in the jungle. He was smiling. He drank wine from the half-empty jug and smoked until the cigarette burned his lips.

“All right. This is all right.”

It went on for an hour. The music. Loud. Loud. Artie rolled another cigarette and passed it. Jerry Spitzer, who had gone in boats down narrow rivers, weaved back and forth.

“Are you high?” Carol asked him.

Her voice was very far away. Very small and soft. Jerry Spitzer looked at her. He giggled. He should have. It was a wonderfully funny remark. Like hello, or good morning. Wonderfully funny. The room was filled with giggles. And music. Carol stood up and took Artie by the hand and they left. Danny went, too. Jerry Spitzer fell back on the bed, his eyes closed, his hands moving with the music that he would never hear again. And after a while his hands stopped moving, and he slept.

Richmond, Indiana, was a sooty lump in the flat green land. Jerry Spitzer did not like it. He said it was too big. Population 47,500.

“What I want,” Jerry Spitzer was saying, “is a place way out on a farm somewhere where if I want to chop down a tree I can chop down a tree, and if my kids want a horse they can have a horse, and nobody bothers you about nothing.”

The plane landed at 4:30 in the afternoon. Indiana summer. Dark heavy clouds blowing across the sky. Lots of sweat. The air feeling thick like the air in a laundry.

There were people waiting for the plane, but none was looking for Jerry Spitzer. He had been expected at nine o’clock in the morning. Jerry Spitzer got in a cab and gave his address. The driver started into town.

“First thing I gotta do is I gotta go over to Anderson and see Betty. I known her since I was 18, but see, when I was over there I wrote her about this Vietnamese girl and I asked her to please send me my rings back but she wouldn’t. So I wrote her again and I said, ‘Look Betty, I ain’t kiddin’. I want them rings back.’ So this time she didn’t write back at all, but her sister does, Sharon, and she writes this real nasty letter and that kinda got me, you know. Somebody buttin’ in like that where they ought to be mindin’ their own affairs. And especially Sharon, boy, she was no one to talk. Hell, she got pregnant and had to get married. So I wrote back to her and said yes, Sharon, you are damn right, it is none of your business, but since you are going to butt in anyway let me just say that at least I didn’t get Betty pregnant.”

“So what happened?”

“Well, that shut Sharon up all right, but I never did get the goddamn rings back.”

The cab drove slowly into Richmond.

“See, my dad was a construction worker and we moved around a lot on account a that and then he was always havin’ problems about money. My brother Joey, he’s 14 now, but he’s had ulcers since he was 9 years old because he always used to hear my ma and my dad fightin’ all the time about money.”

Jerry Spitzer looked out the window of the cab. He was less than a mile from home.

“I guess my ma was finally goin’ to leave my dad except then he died. It was just before I went into the Army. The damn doctor kept sayin’ it was just indigestion and stuff like that and then my dad died and he said, ‘Oh, it must of been his heart.’ That really gets me mad, you know? Those damn doctors.”

There were two white houses next to one another.

“Now slow down, I can’t remember which one it is.”

“You can’t remember where you live, man?”

“Hell, I was only there once. A year ago. My ma just moved there when she started goin’ with this guy, Roger.”

Jerry Spitzer squinted out the window of the cab.

“Wait, I think it’s the first one.”

Jerry Spitzer was home from the war. There was an auto body shop down the street. Behind the house there were railroad tracks and freight trains that moved slowly, steadily past.

The fare was $4.75. Jerry Spitzer gave the driver a five-dollar bill.

Then his mother was out the door. A trim, faded woman of 42. And Joey, and Roger’s little girl, Beth, who was 8.

“Where have you been? Where have you been? I was expecting you at nine o’clock this morning.”

“You ain’t gonna believe this, Ma, but last night we met some hippies. Artie and Danny and what was that girl’s name, Carol. We stayed with them in San Francisco.”

“Oh, San Francisco. When you called I thought you said St. Louis and I told Roger you were in St. Louis and he told me I was crazy that you couldn’t have been in St. Louis because nobody gets out of the Army in St. Louis, and if you were in St. Louis anyway you would of come right on home. I guess he was right, huh?” She laughed.

“They were really cool people, Ma. They believe in make love not war and all that stuff. And in just sayin’ what you feel like sayin’ and doin’ what you want to. I think I might be a hippie. That’s what I might do.”

“Oh, Jerry,” his mother said, and she laughed again, and, with their arms around each other, they walked into the house.

Maybe with most people there is a big fuss when they get home from the war. Maybe they run into the bedroom they knew as a boy and call old friends on the phone and go to parties all week long. Jerry Spitzer turned on the television. The Flintstones. A freight went by and the picture fluttered. He sat, shirtless, in a chair and stared at the screen. He had someone to call. Someone he had met in Vietnam who had married a girl from Muncie. The name was Meyers, or something like that. The guy had said give me a call when you get back and come on over and we’ll go out for a few beers. But Jerry Spitzer had not written down the name and address and now he could not find it in the phone book. “Meyers. I could a sworn he said Meyers.”

Next year, anyway, there would be a big reunion with his buddies from New York. Now New York, that was a place. He would have to go there in 1969 and see his buddies. One lived on Second Avenue, one lived in Brooklyn, and one lived on Long Island.

“If I like it,” he was saying to his mother, “I might even get me a job and live there for a while. Live on the beach in New York.”

His mother nodded. It was almost time for dinner.

“What I thought we might do, Jerry, was, just to keep it simple, was send out to Kentucky Fried Chicken. And then afterward we wouldn’t have any dishes or anything and we could call Roger at the tavern and he could pick us up and we could all go down there for a while.”

Jerry Spitzer did not say anything.

“Jerry? Is that all right?”

“Yeah, sure, Ma. Anything you want to do.”

And so: the homecoming dinner. Kentucky Fried Chicken. The biggest bucket they had. And no dishes afterward. Roger was already at the tavern. The White Horse, in Chester, three miles away. Roger spent a lot of time there, going in after work, after a day at the plant, all hot and sweaty and tired. It was a nice place to go and sit around.

They called and Roger drove down to the house and picked them up. Then they all drove back to the White Horse. Dottie, whose hair was white, brought draft beer to the table. And Cokes for the boy and girl. And a Salty Dog for Roger, who was very friendly. Very glad to see Jerry, very glad that he was home. He gave Jerry a lot of good advice right away. About where to buy a car. About down payments and cosigning. And about the plant. About how the plant was the best place to work because they had the best benefits.

And Jerry said Richmond was too big and he did not want to live there, but maybe he could find a small town and work in a factory there.

“Well, you could do that. Yeah, you could do that,” Roger said.

And then Jerry told him about Artie and Danny and Carol and what nice people they were and how he was thinking maybe of going back out to see them.

And Roger snorted and said, “Jesus Cuh-rist,” and he laughed. Hippies. Ha-ha-ha.

And another lull when Joey talked about this great new movie: The Green Berets.

Then Jerry stood up and said he was going next door to a discount store, just to look around. Joey and Beth went with him.

“Well, it sure is good to have Jerry home,” Roger said.

His mother nodded. “But he sure is edgy.”

“Well, hell, look where he’s been. Look where he’s been. You can’t expect him to come back from someplace like that and be all relaxed right away.”

“I wonder how bad it was.”

“Hell, all you got to do is look at the television to see how bad it was. You know that.”

“Yes, but I wonder how bad it was for him. I could never ask him, of course. That’s just something I could never ask him.”

“Well, all I know is it’s good he didn’t marry that Vietnamese girl like he was going to.”

“Yes, that’s one good thing. But she was probably a very nice girl.”

“Ooh, no doubt, no doubt. But it’s just that she wouldn’t have gotten by out here. You know how people are. There would have been remarks and things. And she wouldn’t have had any friends, and how can she make any if she can’t even speak the language?”

Jerry Spitzer came back and asked for the keys to the car.

Beth, the 8-year-old, came running in. “You should see what Jerry got. He got a whole set of weights.”

Joey came in and sat down. “Yeah, he told me I’d be goin’ in the Army in a few years so I’d better start buildin’ myself up right now. He said I was too skinny for Vietnam.”

It was dark when they left the White Horse. The night was warm. There were mosquitoes behind the house. Jerry Spitzer carried the box of weights inside and down to the cellar. He sat on the floor and opened the box of weights and began to put the set together and explained to his brother Joey how the thing to do was to start out with only a little and then gradually use more and more.

And his mother and Roger stood around and said yes, that was right, that was sure the way to do it.

Part Two: Mark Guzevich

The trip home, for Mark Guzevich, started in green and brown rice-paddy slop. He was lying on his back in this slop, looking up at the sky, and it was funny how the sky had been so clear and blue all day and now it suddenly was fuzzy and gray. And there was a rushing, ringing noise in his head, and behind it he could hear the sound of a gun being fired. That was funny, too. There was one gun, he knew, being fired from right next to his ear. Yet it sounded so far away. Behind all the rushing and ringing. Every once in a while, he would put his hand up to his head. His head felt wet and messy.

Mark Guzevich figured he was dying. It was simple. He had been shot in the head, and people who were shot in the head died. He knew that. The only thing he could think of to do was pray, so, to pass the time, he prayed.

There were two other Marines also lying in the slop. That left only three from the six-man patrol to fire back into the woods where the shots were coming from.

Finally, a platoon of Marines came across the rice paddy and the firing stopped coming from the woods, and then they called for a helicopter to take Mark Guzevich and the other two men away.

In Đa Năng, they operated immediately. Later, a military neurosurgeon would explain it: “The bullet, as it passed through the scalp, depressed a portion of the skull, causing laceration to brain tissue underneath. The surgeons cut through the skull to remove any bone fragments and whatever bullet fragments may have penetrated the brain, and also to cut away that portion of brain tissue that was destroyed. This would be a part of the brain called the frontal lobe. They removed a portion of the frontal lobe.”

But when Mark Guzevich woke up he could think, he could talk, and he could move all the parts of his body. He was very lucky, the doctors at Đa Năng said. A very lucky young man, to lose a piece of his brain like that and still be able to wiggle his toes.

It was raining in Washington. A dirty, late-afternoon, big-city September rain that did not stop. The big plane without windows landed at Andrews Air Force Base at 3:30. A covered ramp was wheeled to the rear of the plane, and a blue bus with racks for stretchers was backed up to the ramp, and men began to go on the plane and carry stretchers off and put them on the racks on the bus.

Mark Guzevich, who was 19 years old, had left Yokohama, Japan, 18 hours earlier. Now he was carried to the blue bus and put on one of the racks. The bus moved slowly through the rain. Mark Guzevich was smiling. “Where exactly is this?” he wanted to know.

The way they did it in other wars was different. Then they would send the badly wounded to a hospital behind the front, and the man would stay there for months.

In this war, it is different. Vietnam: The Jet-Set War. Whoosh, they fly you into battle. Whoosh, they fly you out.

For a while they did it right away — 24 hours from battlefield to backyard. But too many died on the way. So hospitals were built in the Philippines and in Japan and now you go there first. Until your condition has “stabilized.” This means until they are sure you will not die on the airplane. The condition of Mark Guzevich had “stabilized” 17 days after he was shot.

The bus at Andrews Air Force Base took him to a place that is called The Ponderosa. It used to be the base hospital, built in 1941 and looking it. Now it is used only as a resting place for the men who come back from the war. The average stay, according to the Air Force, which is very good at computing such figures, is 16 ½ hours. There are five wards, 130 beds, in The Ponderosa. Mark Guzevich got one with a card at the end that said GULCEVICK.

The doctor came around. “How are you feeling?”

“Fine. Fine. I feel good.”

“How about your right ear?”

“I still can’t hear in it.”

“All right … You’re still receiving medication for the dizziness?”

“Yes.”

The doctor had taken the bandage off Mark Guzevich’s head. “How long have you had those sutures in?”

“A couple of weeks, I guess. Since the operation.”

“All right. I’d like to leave that bandage off tonight, let some air get at the incision. You don’t mind, do you? The bandage is really just for appearance’s sake. We’ll put a new one on in the morning before you leave.”

The doctor moved on. “He’s a very lucky young man,” the doctor said.

Then there were the Red Cross ladies. No parades for the wounded. No kisses or confetti. But Red Cross ladies with wire baskets.

“Would you like some toothpaste?”

“I have some, thank you.”

“How about some cigarettes?”

“I don’t smoke.”

“Well, here, at least have a bottle of soda … and how about some aftershave? It’ll make you smell pretty in the morning. And let’s see, how about a comb?”

Mark Guzevich looked at the Red Cross lady.

She looked back at him.

“Oh, no, I don’t suppose you need a comb,” she said.

It was dark outside now. Mark Guzevich had eaten dinner and made his free three-minute phone call home. His family, crying and excited, had talked more than he had. They had known he was coming back — he had told them in a letter from Japan — but they had not known when and they had not known how he would be. All they had heard was “head injury, critical condition,” and they had been afraid.

“My dad was telling me, I guess they’re really making me out to be some kind of a big hero at home. It was in the paper about me being hit again and they said this time it was in the head and it was critical and down at the courthouse in Elizabeth — my dad’s a court attendant — I guess all the judges and lawyers and people like that found out and there’s really been a big fuss. Boy, I’d like to be there tomorrow when he starts telling people I’m home.”

Mark Guzevich had been shot in the hand in June. The bullet had torn some tendons. He was sent to Guam to do exercises with his hand. He had been back in action just two weeks when the bullet hit him in the head. He was a private 1st class in the Marines. A year out of high school in Kenilworth, New Jersey. He had been a fullback. Guzevich: Number 44.

Now the bandage was off his head so the air could get at the incision, and there was part of his brain missing and he could not hear in his right ear and they told him no drinking for a year because there was danger of seizure, and he still had nine more months to serve in Vietnam.

“How can they send you back? You’ve been shot twice. Shot in the head.”

“That doesn’t matter to the Marines. All the Marines do is co

unt. The Vietnam tour is 13 months. I’ve served four. I’ve got nine to go.”

“Yeah, but with an injury like this …”

“I don’t know. Maybe you’re right. Maybe they won’t send me back.”

“Do you want to go back?”

“Are you kidding? Want to go back? I never want to see that place again or hear about it as long as I live.”

They put him on a plane to Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, and the plane landed in the sun, and there was a good saltwater breeze. They put him on a blue hospital bus; on a rack, in the back.

“I joined the Marines — well, I’ll tell you — I guess just because I was 18 years old and all gung-ho. I thought the Marines were the best. It’s no secret that their training is tougher than anybody else’s, and I figured it would be good; you know, make a man out of me.” He put his fingers to his head and laughed. “Maybe they did,” he said.

“I’m the only guy from my class who’s been to Vietnam. I think I must appreciate things a little more now because of it. Over there, for instance, getting cleaned up once a week really made you feel good. Or if you could stay dry for a whole day, that was a big thing. That was wonderful. Or just staying alive for one more day. You were thankful at the end of every day. I mean you really thought about it. And look, in high school who thinks about staying alive? You take it for granted. Everybody stays alive except old people and you don’t hardly know any of them. Then you get over to Nam and — well, like I said — I’m 19 years old and maybe that’s not old but I feel old. I saw a lot of war. And I saw a lot of guys, I mean, hell, hundreds of guys get messed up.”

A man in a white suit came back to ask him how he was feeling. He told the man he was feeling fine. The bus ride was much bouncier than the plane had been. The rack he was lying on kept jerking up and down.

“That first time I got shot,” he was saying, “we were out on patrol and I was second, right behind the point man. We got ambushed and right away the point man got killed. Then, in the afternoon, after we laid low for a while, we had to come down the side of the hill and cut our own path through the vines and all that, and let me tell you it wasn’t easy. It took us six hours to get back to camp, and we had to carry the point man’s body all the way.

“I might as well tell you, I guess. I’m more of a hawk than a dove,” Mark Guzevich said. “I mean I got no love for the gooks or any of that stuff, but we have a commitment and we can’t just come crawling home with our tail between our legs. At least that’s the way I feel. I think we have to stay until we get a just and honorable peace.”

“What does that mean?”

“I think it means until we make sure that they’ve got a government that’s strong enough to stand up. It doesn’t have to be just like ours, but it ought to be some kind of a democracy.”

“Do you think that will ever happen?”

“I don’t know. I think they’re getting better. Look, what I’m telling you is just my opinion. If these hippies and people like that feel different — well, that’s fine. I can understand that. And if they want to demonstrate, that’s fine, too. As long as they don’t come around and say, ‘Ha-ha, we’re glad you got shot because you didn’t belong there anyway.’ I wouldn’t like that too much.”

He was quiet for a while, thinking. And looking up at the roof of the bus. The hospital was not far away.

“I know it’s not the same as when my father fought. He was in the Marines in World War II and that was to save our country, and I couldn’t say that this is the same kind of thing.”

“Does that make it harder to risk your life?”

“I guess it would if you thought about it. Sure, I guess it would. But you don’t have time to think over there; you just try to get through day to day.

“Now — now I will have time to think. And like I say, I don’t want to go back.”

At St. Albans Naval Hospital there was a sign: “Appropriate attire for female visitors does not include micro-mini skirts, short shorts or bare mid-riffs.”

There are 1,400 patients at St. Albans, including 450 to 500 Marines, most of them wounded in Vietnam. Mark Guzevich was put in Ward C-3, neurosurgical, where men hurt worse than he was, men who had lost more than a portion of a frontal lobe, were lying in beds, staring and moaning and babbling. Others were reading movie magazines or comic books.

“This is a very lucky young man,” said the doctor in charge. “Now I wouldn’t say there’s absolutely no damage. I wouldn’t say quite that. But there does not appear to be any damage that will affect him. Let’s put it this way. If Ted Williams were to lose a portion of a frontal lobe, he’d still be Ted Williams and he could walk and talk and still probably play baseball, but maybe he would not be able to hit quite the same way. Maybe on that level there would be just that shade of difference. But when you’re talking about that boy in there, it’s different. Again, I would not say there is no damage, I would not say that at all. But once his hair grows back nobody will be able to tell him from you or from me.”

Mark Guzevich was looking out the window. Đa Năng was the other side of the world, another world.

“My parents are really happy,” Mark Guzevich was saying. “They’re coming over tomorrow. They don’t believe I’m really okay. I had to keep telling them. They were worried about brain damage and all. Boy, this sure is decent. You know, bringing you back to a hospital so close to home.”

In the bed across from him, two attendants were trying to feed a peanut butter and jelly sandwich to a man who weighed less than 100 pounds. The man could not talk or sit up. He lay for hours at a time on his side with his eyes open until someone came to change his linen.

“Come on, just try to take a small bite.”

The man made a noise. His skin was saggy, like an elephant’s, and the bones showed through.

“Come on, try to sit up by yourself.”

“He’s much better now than he was when he came in,” a Marine sergeant said.

And Mark Guzevich picked up the copy of Time magazine he had been given and started to read about Denny McLain, the baseball player on the cover. Once his hair grows back, nobody will be able to tell him from you or from me.

Part Three: James Waller

The bodies come to Saigon in rubber bags. Men in green smocks are waiting in the room, which has pale green walls. When the bodies come, the men open the bags and slide the bodies onto steel platforms that rise to waist level from the floor. Then the men try to find out who the bodies used to be.

Sometimes it is hard to tell about the bodies right away. Sometimes the men cannot tell for hours, even days. When this happens, or simply when the embalming room is full, the bodies are put in a refrigerator. There are actually three refrigerators, walk-ins with heavy doors and handles that click, like those in the back of a butcher shop.

The bodies lie here on racks until someone finds out who they were or until there is a table open in the room where they will be embalmed.

The smell is always here because there are so many bodies, whether the big doors are open or closed, but the men who work with it are used to it and do not mind. Occasionally a new man comes in who cannot take it. He is transferred quickly, without disgrace. The major understands.

Basic embalming: “The fine points of cosmetology we leave to the mortician back home,” the major says. “But we send, oh, I’d say 70 to 75 percent home viewable, and we think that’s something to be proud of.”

When the embalming is done, the bodies lie and wait through the night. Eight hours, at least, for tissue to be preserved. Then it is morning and time for packing to begin.

The first body is carried into the packing room and set down next to a table. There is a thin plastic bag waiting there. A man in a sleeveless green smock, sweat already rolling down the sides of his chest, turns down the front of the bag: a ship steward turning down the bed. Strips of cotton are laid inside the bag. Then a powder which hardens at the touch of moisture. Just in case there is a leak.

Then the first one — cotton over the eyes and crotch — is put inside the plastic bag, and they wheel the table to the vacuumer. The vacuumer reaches into the plastic bag with the hose in his hand and sucks out all the air. His machine whirs and the plastic crinkles as it collapses around the body.

Then masking tape around the top of the bag so no air can creep back in and undo the embalmer’s work during the long flight home.

And the body moves down the line. A sheet is wrapped around the plastic and more men with masking tape move in. They, too, work quickly, wrapping the tape in thick, sticky brown strips around the sheet.

In the front room there is a chart:

AVERAGE PROCESSING TIME PER REMAINS

Receipt and Verification of Identity — 30 min.

Embalming Operations* — 4 hrs. 15 min.

Preservation of Body Tissues — 8 hrs.

Packing — 10 min.

Out Processing — 30 min.

Total — 13 hrs. 25 min.

* Severely mangled, charred or badly decomposed remains can require from 10 minutes to six hours depending on the condition.

On Saturday, August 24, James Waller’s mother got a letter.

Dear Madam: This is in answer to your letter concerning your son James Waller US 52 814 303.

I have spoken with James and he is doing fine. His job assignment, as you know, is as a rifleman in his company. His company commander and first sergeant have both stated that his performance has been outstanding and that he is highly respected and admired by his leaders and the personnel assigned to his company. I want to thank you again for your letter addressed to me concerning your son James, and again state that if you have any additional questions, please feel free to write to me. FOR THE COMMANDER: Robert M. Thomas, Captain.

On Monday, Mrs. Waller received another letter. This one was from James. He said he would be needing his good pair of eyeglasses in four months because he would be getting five days off and going to Honolulu. He also said he was trying to read his Bible like she had told him to, but it kept getting wet. He enclosed a picture of himself and two friends, grinning, dressed in fatigues.

A man in a uniform came to the Wallers’ house that night. He told them James had been killed. He said it had happened in an attack on the base camp in the middle of the night. He said a telegram would follow. And there would be a Capt. Woolley calling soon to help with the funeral arrangements.

The Wallers got a telegram:

THE SECRETARY OF THE ARMY HAS ASKED ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET THAT YOUR SON PRIVATE FIRST CLASS JAMES WALLER DIED IN VIETNAM ON 24 AUGUST 1968 AS A RESULT OF A WOUND RECEIVED WHILE IN BASE CAMP WHEN ENGAGED HOSTILE FORCE IN FIREFIGHT. PLEASE ACCEPT MY DEEPEST SYMPATHY. THIS CONFIRMS PERSONAL NOTIFICATION MADE BY A REPRESENTATIVE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE ARMY.

KENNETH G. WICKHAM

MAJOR GENERAL USA

The newspapers called and put stories on page 3: “N. Phila. Soldier Dies in Vietnam Firefight.” One of them used a picture. Mrs. Waller told the papers that she did not know where in Vietnam her son had been stationed and that, no, he had not commented on the war in his letters. He had always been cheerful and generous, she said, but the papers did not print that.

Then she got a longer telegram:

THIS CONCERNS YOUR SON PFC. JAMES WALLER. THE ARMY WILL RETURN YOUR LOVED ONE TO A PORT IN THE UNITED STATES BY FIRST AVAILABLE MILITARY AIRLIFT. AT THE PORT REMAINS WILL BE PLACED IN A METAL CASKET AND DELIVERED (ACCOMPANIED BY A MILITARY ESCORT) BY MOST EXPEDITIOUS MEANS TO ANY FUNERAL DIRECTOR DESIGNATED BY THE NEXT OF KIN OR TO ANY NATIONAL CEMETERY IN WHICH THERE IS AVAILABLE GRAVE SPACE. YOU WILL BE ADVISED BY THE UNITED STATES PORT CONCERNING THE MOVEMENT AND ARRIVAL TIME AT DESTINATION. FORMS ON WHICH TO CLAIM AUTHORIZED INTERMENT ALLOWANCE WILL ACCOMPANY REMAINS. THIS ALLOWANCE MAY NOT EXCEED $75 IF CONSIGNMENT IS MADE DIRECTLY TO THE SUPERINTENDENT OF A NATIONAL CEMETERY. WHEN CONSIGNMENT IS MADE TO A FUNERAL DIRECTOR PRIOR TO INTERMENT IN A NATIONAL CEMETERY, THE MAXIMUM ALLOWANCE IS $250; IF BURIAL TAKES PLACE IN A CIVILIAN CEMETERY, THE MAXIMUM ALLOWANCE IS $500. REQUEST NEXT OF KIN ADVISE BY COLLECT TELEGRAM ADDRESS: DISPOSITION BRANCH, MEMORIAL DIVISION, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, WUX MB, WASHINGTON, D.C. NAME AND ADDRESS OF FUNERAL DIRECTOR OR NAME OF NATIONAL CEMETERY SELECTED. IF ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONCERNING RETURN OF REMAINS IS DESIRED, YOU MAY INCLUDE YOUR INQUIRY IN THE REPLY TO THIS MESSAGE. PLEASE DO NOT SET DATE OF FUNERAL UNTIL PORT AUTHORITIES NOTIFY YOU DATE AND SCHEDULED TIME OF ARRIVAL DESTINATION.

The body of James Waller arrived at the Air Force base in Dover, Delaware, on Tuesday, September 3. It went immediately to the base mortuary, where the man in charge noted the recommendation that had been attached to it in Saigon: Non-viewable.

That meant that James Waller would skip a step in the process. He would not have to be cosmeticized. Only the rough work, only the basic essential health procedures are taken in Saigon. The fancy stuff, the detail work, that is all done in Dover.

Then the escort detail was notified and Sgt. Ollie Dyson, of Chicago, was told to report at 9 a.m. Wednesday to accompany the body to the Ray Funeral Home, 1525-27 West Dauphin Street, Philadelphia.

James Waller was removed from the aluminum carrying case and placed in a metal casket, which was sealed. The carrying case was washed and stacked with the others to await return to Saigon.

The Ray Funeral Home in Philadelphia was not expecting James Waller’s body Wednesday morning. Mrs. Deso Ray, the wife of the owner, said no telegram of notification had come. It was 11 o’clock and hot. Ollie Dyson and the hearse driver and a helper of Mr. Ray’s, named William, carried the casket up the steps. Mr. Ray was not there. The casket was placed in a shaded room in the rear of the funeral home; the gray metal was covered by a bright American flag.

When Mr. Ray returned, Ollie Dyson handed him a letter:

To: Receiving Funeral Director:

1. These remains have been shipped to your funeral home consistent with the desires of the family.

2. We are sorry that the circumstances of the deceased’s death precluded restoring the remains to a viewable state.

3. Before shipment, the remains and casket were inspected by Air Force representatives and found to be in satisfactory condition.

4. We would appreciate your cooperation in explaining this matter to the family should they question the reason for a sealed casket.

Sincerely,

DAVID J. AFFHOLDER, Captain

USAF Mortuary Office

Mrs. Waller could not understand about the casket.

“Don’t worry about it,” her husband told her. “It doesn’t make any difference.”

“But how do I know it’s him?”

“It’s him.”

“But why can’t we see him?”

“Don’t worry about it. What you want to see him for anyway? He’s dead.”

“If I could just see him one more time.”

“Stop talking about it.”

There was to be no wake, they decided. The funeral would be Monday night and burial Tuesday morning. They got a letter from Gen. Westmoreland:

Please know that the thoughts of many are with you at this time. The passing of your son, Private First Class James Waller, on 24 August, in Vietnam, is a great loss not only for his fellow soldiers but for his country as well.

I know that words can do little to relieve your grief just now but I hope that you will find comfort in the knowledge that through your son’s sacrifice he will live in the hearts of all who desire peace and freedom.

As our Nation strives … human dignity which we hold dear … most distressing thing … through their devoted service … remain strong and our purpose steadfast. …

At 4:30 Wednesday afternoon, five and a half hours after the body had arrived, the final telegram came:

REMAINS PFC JAMES WALLER ARRIVE PHILA. PA. APPROX 1030 AM 4 SEPT VIA HEARSE RAY FUNERAL HOME NOTIFIED.

Mrs. Waller was sitting at her dining-room table. She was very tired. Her husband was with her. He was a janitor at the Boyles Galvanizing and Plating Company. He wore a medal with a picture of Martin Luther King. James had been their second son. Sidney was one year older. There were also two younger daughters.

“The insurance man was by today, and he said I ought to frame that letter,” Mrs. Waller said to her husband.

He was staring at the floor.

“Did you hear me? The insurance man says we ought to frame this letter from the chief of staff.”

“Yes, I hear you.”

“Well?”

“Well, well — well, what? Fine. Frame it.”

Mrs. Waller put the letter down and picked up the picture that James had sent her from Vietnam.

“Poor James,” she said. “He only just got there in June. He didn’t know what it was all about. I told the papers he didn’t have any comments about the war. Well, he did have one. He wrote and said, ‘Mom, this whole thing is crazy. I don’t understand it.’”

“Who does understand it?” John Waller said.

Mrs. Waller did not answer.

“If they had only given him a chance,” the father said. “They come up on him in the middle of the night and he was probably sleeping and never even saw them. He was out there in the front row for two months and then he goes back for a rest and they sneak up on him in the middle of the night.” John Waller shook his head.

“He could have gone to jail,” Mrs. Waller said. “He could have been one of those boys who goes to jail because they don’t want to be in the war.”

“He’s not that type.”

“No, but if he had done that he’d of been alive.”

“He’s not that type. To go to jail. That wasn’t how James was.”

“No, that’s right. James always did what he was told.”

The father nodded.

“He never went anywhere that he didn’t come back with a piece of paper that said how good he was,” Mrs. Waller said. “He got one, look here, from Dobbins, where he went to high school, and one from the R.W. Brown Boys Club, and here, one from the American Legion.”

“And then they sneak up on him in the middle of the night.”

“James never want to do no killing anyway.”

“No, that’s right. He told the Army he wanted to be a clerk.”

“But they told him he couldn’t because he didn’t have experience.”

“He didn’t have experience killing either.”

“That’s right, he didn’t have no experience with guns.”

“But that didn’t matter, did it?”

“No, they didn’t care about experience with the guns.”

“What I don’t understand,” John Waller said, “is if they could teach him how to kill why couldn’t they teach him how to type?”

They came down the steps with the casket very slowly. There were only three of them to carry it, which made it heavy. It was six o’clock Monday night. The sun was still warm, the air heavy and hot, as the American flag and the box underneath it were put into the back of the Cadillac hearse.

When they got to the Thankful Baptist Church, 10 minutes away, George Ray asked about flowers.

“There’s not very many,” a church custodian said. “I put what there is up front.”

There were two wreaths that said THE FAMILY, one that said THE NEIGHBORS, and one that said THE GANG.

George Ray placed them symmetrically around the casket.

“I’ll be back about a quarter to eight with the family,” he said.

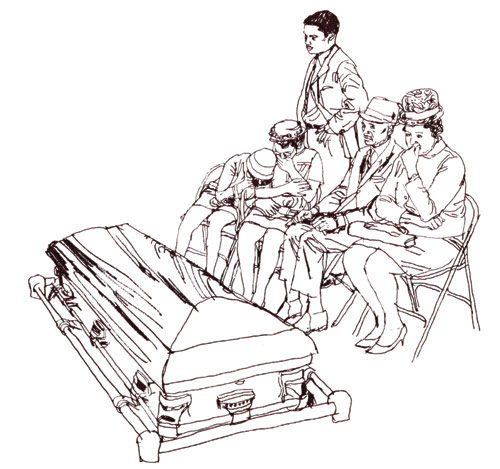

It was cool inside the church. There was green carpeting on the floor and the pews were light brown, well-waxed. James Waller’s casket was in the front, near the altar, where it was very still. The funeral began with an organist playing “America the Beautiful” in a thin and quiet way. Then there were hymns and readings from the Bible and then a kid named Glenn Kennedy, a kid who had been a friend of James Waller, got up to read all the cards and telegrams that had been received.

There were telegrams from the governor and the cardinal and Senator Clark, who was running for re-election, and Representative Schweiker, who was running against him, and from many other people who did not know what it smells like in North Philadelphia along Dauphin Street where James Waller grew up, or what it smells like in the mortuary in Saigon.

Then a man who had taught James Waller plumbing at the Murrell Dobbins school got up and said what a hero the boy had been, dying for his country, and how much more representative he was than these hippies, and wasn’t it a shame that the good ones had to go, and maybe someday soon the country would all pull together and unite behind the war and then the “other forces would see the futility of continuing the struggle.”

Then a kid named Edward Marks, a friend in an Army uniform, who had just come back from Vietnam, stood up. He tried to talk but it was too hard and he sobbed, and Mrs. Waller, in her seat, gave out a little cry and lurched forward and began to cry, and Edward Marks just said, quickly, “He was a wonderful kid,” and hurried away from the altar.

Then later, at the end, after an hour and a half, Mrs. Waller suddenly stood up and stepped out of her pew and walked to the casket and before anybody really noticed her, she screamed and threw herself on the casket and began pulling at the flag.

The screams came from somewhere very deep and they filled the church and this big woman whose son had died had the flag off the casket and was pressing her face into the bare gray metal when they got to her.

She fought them and she kept on screaming, and in the pew the teenage daughter began to cry, “Jesus … Jesus … Oh, Jesus …” and there were four men around James Waller’s mother, and they were holding her with a very tight grip.

When they got her back to the pew, George Ray came over to Ollie Dyson and whispered, and Ollie Dyson walked to the casket and put the flag back on and straightened it.

The next day was quick. There were clouds and one of the first winds of autumn was blowing brown leaves from the trees. Philadelphia National Cemetery was small and neat, with the rows and rows of identical white tombstones sweeping across the grass. There was a four-man firing squad down from Fort Dix, and a six-man honor guard as pallbearers, and a bugler who stood alone under a big oak tree by a fence. There were only four chairs for the family by the grave, and Sidney, the brother, had to stand. He was 21 years old and he was all stooped over like his father.

At the end, everyone walked by and put a flower on the casket. The flag had been taken off and folded in that tense ceremony that the military always has with the flag, and then it had been given to Mr. Waller. The people came by and put their flowers on the gray metal, maybe 50 of them all together, and then Sidney Waller put his flower there, and the two sisters, and Mr. Waller, and finally James Waller’s mother, who did it very quickly and quietly and moved away with her husband’s arm around her.

They walked back to their cars in the driveway in the middle of the cemetery and the sun was out now and it was still summer. A man in a red T-shirt drove a power mower to James Waller’s grave and began to fold the metal chairs.

Another man, in a green shirt and green pants, swept all the flowers off the casket with his arm. Then the two men got down on their knees and they were joined by a third man in green pants and there was another man in a suit who was holding a clipboard, and the three of them began to work while the man with the clipboard stood there, and in the driveway 50 yards away the family of James Waller sat in the car.

The casket had rested on two green planks above the open grave. Now the men pulled the planks away and the casket was on two canvas straps that were wound around a set of silver poles that could be turned when the screws were loosened.

The men loosened the screws and the poles began to turn as the weight of the casket strained against the straps and the casket lurched a bit and one end slid down a foot and then the other end was lowered to make it even.

In the car in the driveway, Mr. and Mrs. John Waller watched the gray metal disappear and Mr. Waller held the American flag in his lap.

Epilogue

Mark Guzevich did not go back to Vietnam. He was kept in St. Albans Naval Hospital until the second week of November and then sent to a Veterans Hospital in New Jersey, which allows him to go home on weekends. “I feel pretty good,” he says, “but the doctors still don’t know about the ear. They say the hearing might come back and it might not.”

He will soon be out of the Marines. A medical discharge. But he has nowhere to go, at least until the spring. “They’ve decided to put a plate in my head, but they’re not going to operate until February or March. For now I guess I’ll just be staying at the hospital. They’re giving me aptitude tests, and when they’re through with those I’ll start thinking about the future. I’d like to go to school, but with this operation coming up I guess there’s really not too much of a rush.”

Five weeks after he came home, Jerry Spitzer and Betty were married. “It was kind of quick,” he said, “but she pretty well nailed me down.” They live in Anderson, about 40 miles from Richmond, and Jerry works in a factory. He often thinks of Vietnam. He has even thought about returning. “I kind of feel sorry for those people over there,” he says. “Of course, I don’t think I actually would go back.”

He has not heard from the men he fought with. No plans have been made for the reunion in New York; it is not likely they will be. His days move quickly, and “except for all these taxes they got out here,” he is content.

—“Vietnam: Three Who Came Home,” February 8, 1969

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now