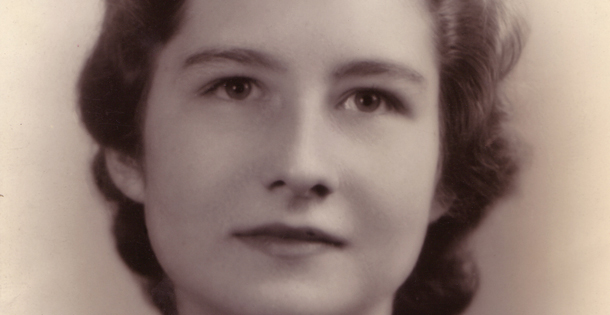

In 2001, on a beautiful spring weekend, I accompanied my mother to her 60th college reunion and got a picture of the young woman she once was.

Thursday, 11:45 p.m. Leftovers

I am visiting my mother at her New York City apartment. Tomorrow, we’ll begin a full weekend of activities for her Vassar College reunion in Poughkeepsie, just an hour and a half north of the city in a chartered bus. We’re sipping beer, and she’s telling stories about old friends and cherished college moments. Finally it’s bedtime.

But first, we must boil the strawberries.

“They could go bad,” she explains, dumping the clinging dregs from the green plastic pint container into a saucepan.

My mother, Jean, is a lot of things — fiercely intelligent, archly funny, and sometimes a bit nutty — but she is never wasteful. She seals up her strawberry mush in a recycled mayonnaise jar, puts it in the fridge. Then she climbs up on a step stool and roots around in an overhead cabinet until she finds another container. Into this one goes a cup of coffee left over from dinner.

Friday, 11 a.m. Some Kinda Wise Guy

The cab driver who’s taking us to Midtown to catch the Poughkeepsie bus is one of those garrulous New York City cabbies out of central casting. I happen to mention we’re going to my mother’s college reunion, and he replies, “But she can’t be your mother. I thought she was your sister.” I roll my eyes, but my mother gets right into it with him: “Well, if your eyesight is so bad, maybe you shouldn’t be driving.”

He clams up for the rest of the ride.

Friday, 3 p.m. The “Ma-Ma” Degree

The reception for the class of ’41 is in a large central dormitory and administration building simply called “Main.”

The room for our reception is grand, with high ceilings and walls decorated in an ornate jade Chinese wallpaper of geese and lily pads. Lest we forget where we are, foot-high golden Vs are tucked into the molding in the four corners of the room.

I meet one of my mother’s classmates, Marta, who is extremely pale and so thin you want to reach for her arm when she stands or takes a step. Her blue eyes are sharp. She tells me about coming to the U.S. from Austria right before the war. How frightened she was the time she heard a fellow shopper in a New York department store loudly criticizing Roosevelt. “Back home, you could get shot for saying such things,” she says.

Marta also tells me another story that I will hear echoed over the next two days. Graduating as a science major, she wanted to study aeronautical engineering. She was told she qualified for acceptance to Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, but administrators warned her it would be “difficult” for her there, since there were no toilet facilities in the labs for women. “So instead of an M.A.,” she tells me, “I became a Ma-Ma.”

This was not, it hardly needs to be said, an era when women easily became professionals, even those who were college graduates. Consider the statistics for the class of ’41: Only one-fourth worked outside the home for a full 20 years. Of 252 graduates, 166 described their roles as “chiefly housewife.” More than half reported doing regular volunteer work. And of the 74 who’d held full-time jobs, more than half were, like my mother, teachers.

Another occupation has become more common in recent years: caregiver. My mother was nurse to her mother and, later, to my father, who had Alzheimer’s. It was no easy task, but I never heard her utter a single word of complaint.

One woman tells me she visits her husband in a nursing home all day, every day, even though he no longer recognizes her. “My friends told me I shouldn’t go so much,” she says. “So for a few days I stayed away. When I came back, the nurse said he’d stopped eating. So now I go.”

We are interrupted by Judith, a vigorous woman in a bright red dress who is breathless with excitement. “Do you want to see my diamond pin?” she asks.

“Okay, sure,” I say politely.

The joke is on me. She opens a jewelry box and shows me a dime and a safety pin. Should have seen this coming: Judith is wearing huge red earrings, one says IN and the other says OUT.

Friday, 8:30 p.m. Continuity

My mother has something to tell me. We’ve just finished a buffet dinner under a white tent, sitting with her very dearest old friends, many of whom she’s kept up with through the years. They’ve updated each other on travels, aches, medicines, children, grandchildren, husbands. We pass around the script for a skit, written mostly by Ruth, a professor’s wife, that they’ll perform at tomorrow night’s banquet. The topic is language, words that have disappeared (rumble seat, nylons) and words that have gained common currency but still feel alien and amusing to them (user-friendly, glass ceiling, significant other).

The subtext, of course, is change, something that’s on my mother’s mind a lot lately. But as we’re sipping coffee, she leans over and tells me something that is about not-change — her theory of continuity.

Memories can be handed down from generation to generation, my mother believes. When she was very young, her grandmother lived with her in their New York City apartment. My mother would regularly brush out her grandmother’s long hair. And while she was doing it, her grandmother would describe brushing her own grandmother’s hair. This earlier brushing took place in New Milford, Connecticut, where the family had lived for generations. It was a town my mother knew well. And so, she says, her grandmother’s memory eventually became her own. She describes for me the sun coming in the south-facing window of the sitting room in her grandmother’s childhood home, the feel of the wooden bristle brush in her grandmother’s five-year-old hands. As she describes it, she closes her eyes, and I can see she’s really there, brushing her great-great-grandmother’s hair. I do a little calculation: The scene she’s depicting would have taken place in the 1850s.

Friday, 11:30 p.m. “It’s Ther-a-peu-tic”

My mother and four friends have passed up the obvious option of going to bed. Instead, we’re squeezed around a table at the Mug, a basement campus pub. It’s packed with young men and women, recent graduates sharing their own reunions. (Vassar went coed in 1969.) Donna Summer is pulsating from large speakers. Margaret, one of our crowd, is dancing exuberantly by herself. (As a girl, she was considered clumsy, she tells me. So she was sent to study dance with a disciple of Isadora Duncan, and she’s been dancing ever since.) She insists that we all join her on the crowded dance floor. The six of us gather in a circle. We dance. Ruth, who’s tall and slim but not what you’d call athletic, makes determined up-and-down moves with her fists. My mother, whom I’ve never seen dance to rock, much less disco, gamely shuffles her feet a bit in time to the music. “Come on,” Ruth shouts to her, pumping her hands up and down. “It’s ther-a-peu-tic!” My mother smiles a wry smile and pumps her hands, just a little.

Later, as I’m fighting my way through the dense crowd, ferrying clusters of full beer mugs from the bar to our table, a woman with a “Class of ’96” badge blocks my path and demands, “What year are they?”

“Class of ’41.”

“Awesome!” she squeals.

Saturday, 7 p.m. An Old Memory Made New

The banquet dinner for the class of ’41 begins with a remembrance of classmates who have died. The names, more than 100, are listed on a program. I am struck by how unemotionally this tribute is received. Of course, by a certain age, death might be a familiar presence, I think to myself.

But then the speaker says, “… And, I’m sorry to report that since the printing of this list, two more of us have passed away.” A gasp punctuates the silence as she names the newly dead.

After dinner, my mother and her friends stand and perform their skit. It begins as a series of comments about life in 1941 (“I’ve never seen TV, but I’ve heard of it.”), then flashes forward to 2001, when, according to Ruth’s script, most young people are pretty clueless:

“Do we know where the trade winds are? Or how to find Oslo and Shanghai, Kinsale and Petra?”

“Yes.”

“But our grandchildren don’t.”

“They know Planet Krypton, but they can’t find Crete.”

There’s more in this vein. Then comes the closing line, which draws a good laugh: “You just can’t trust anyone under 80!”

Suddenly, I see them as they were in their early 20s, beautiful, privileged, exquisitely well-educated. I can imagine them putting on a skit like this one — witty and satirical and just a little bit smart-alecky. Each of them is intimately acquainted with the lessons of the Depression. Most of them expect to go forth, marry, and raise children. The European war has already begun; in a matter of months, it will become America’s war too. And so my understanding of my mother’s precious years at college now includes a living picture. She has given me the gift of a memory. She has given me a piece of her life.

Steven Slon is the editorial director for The Saturday Evening Post. Jean Slon passed away in 2008.

This article appeared in the May/June 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more inspiring stories, as well as art, travel, trends, fiction, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This was a very thoughtful, kind thing you did for your mother Steven. I’m sure it meant a lot to her over the final years of her life, as it does to you now. You definitely did get a picture of who she was, and a piece of her life. Her photo shows she was a beautiful woman as well.

My mom was a teacher too; high school English in the early ’50s after graduating from Immaculate Heart College in 1950. Although very different, there’s a commonality here in that my mom took me to Immaculate Heart in Hollywood in late 1968 for the unveiling, of all things, Sister Corita Kent’s ‘happy’ collage pop art cover that was soon to make the cover of The Saturday Evening Post, bridging 1968 and ’69!

Mom was only 40 then, and I was 11. It was great seeing my mom so happy herself, and for Sister Corita. She’d been ready for the late ’60s many years before society was ready for her art. The event was a big deal and no doubt contributed to my appreciation of the Post at a young age. Her cover is a particular favorite; I just love it! (Thank you art.com)

Sister Corita passed away in 1986 at age 67 from cancer, far too young. My mom in 2013 at 85, after years of suffering from Parkinson’s disease. She didn’t know who I was near the end. I’d gotten false alarms from the rest home she could ‘go’ any time, seeing her for the last time on Friday, 12/13/13. This time though I knew she did know me from her eye contact and smile. Seeing her there with a breathing machine, tubes and an oxygen mask was very hard and I completely broke down while hugging her. I stopped by Sunday and again Wednesday, but she was fast asleep both times.

On Friday the 20th the phone rang at 4 am, and I knew before picking it up. I had a premonition Thursday night around 11 pm, and still feel guilty for not driving over right then despite being exhausted from that day.