At spring twilight, with fog fingering round the bay heads and twisting over the ridges in creeping pearl-yellow tendrils, Old Hsiao started to pull in his nets. The great bay, an inland sea in itself, spread about his ungainly little boat in a vast glassy sheet on which hull, stubby mast, short boom and stocky fisherman were reflected and foreshortened to slowly dancing shadows. And it was as the last of the small-mesh shrimp nets and floats were drawn up, to be draped over the boom, that he found the yellow buoy and the thing attached to it by a deep-lying line.

All day he had farmed the shallow bottom, reaping the crop of tiny crustaceans from acres of rock, sand, mud and weed. But on the day and night before, a southeast gale had snorted over this protected harbor, roiling it until it lifted a low organ note of surf along the shores, and the catch was nothing special. The buoy with the little waterproofed package at the end of its line was his most spectacular haul.

He sat on the after fish hatch, turning the object over thoughtfully in his wrinkled brown hands. Then his fingers picked it free of its waxed-cord bindings. Slit eyes set in a leathery gnome’s face as crinkled as a brown prune peered down at his find. What he saw caused him to shuffle boots on decking, push the black knitted cap to the back of his head, hunch up the rubber coat collar in bewilderment. He was a simple man of frugal habits who had spent most of his long life on the little shrimp boats of the coast, and it dawned on him slowly what this queer stuff was that had drifted into his net with the vagrant winds and currents from the port city and the Gate.

Around his craft in the violet evening, fog swirled softly, lifting and lowering its erratic curtain to reveal glimpses of the far opposite shore and the faint lacy arch of bridges. Now his acute ear caught the whisper of sand shifting with the ebb tide among stony outcrops at Roqueno Point, and frogs harmonized across the rising flats as the sea retreated.

Presently he slipped the package into his pocket, kicked up his clanking engine and entered the housing to spin the wheel. And as dusk strengthened, the shrimper groped blindly into its moorings at Riggs Cove, unerringly guided by the years of bucking these vague tidal sets and the steady sound of a plaintive sea wind strumming in gnarled cypress and ironwood on the hillside above the anchorage.

There were no other boats in the isolated backwater of the bay shore; he was berthed in solitude along the ancient drying dock. Other shrimpers had prudently departed in their bright fleets long ago from this mist-shrouded pond. But Old Hsiao hung on tranquilly in his snug harbor, content in the ghostly assembly of weather-beaten shacks that marked the once-swarming shrimp camp, satisfied with the company of a handful of stubborn folk who peopled the curving beach.

Tonight he did not wait to unload his catch. He stumped up the sway-backed dock and through the pungent curing shed, and entered the warm lamplight of Pastorino’s Grill. He laid the odd little packet on the wooden counter.

“What you got there, Ole Shoe?” Joe Pastorino demanded, brown Sicilian eyes smiling from the dark-lined and aging face. “You been beachcombing again?” He set a coffee cup before his crony. Behind him steam rose from a pot where rich and creamy chowder simmered in aromatic proof of the former ship’s cook’s art.

“I think dope, mebbe,” Old Hsiao said calmly, sipping from the cup.

“Dope!” Pastorino was shocked and unbelieving. “What you mean, dope?”

His voice brought Young Joe to the swinging kitchen door, standing tall and vigorous like his father, wiping capable hands on an apron. Folks along the looping north bay shore said the Pastorinos were much alike, both as fine cooks and as great talkers, except Old Joe had been up and down and around the world in the galleys of merchant ships, while Young Joe had only been as far away from the cove as Korea, where he’d gone once in an Army suit. But Young Joe had promise, he was building a troller of his own on Kekkonen’s ways, and was even getting a string of crab pots together for winter.

“Dunno,” Lao Hsiao shrugged, opening the package with one casual hand. “Look like funny stuff, huh?”

Young Joe looked.

“Heroin,” he pronounced. “Seen it when the MP’s took a load off some native guys over across. Pure, likely. Lotta money there, grandpa. How you figure it?”

The fisherman shrugged again, and his indifference was genuine. “Mebbe bad fellas bring on cargo ship f’um China, scairt cops catch ‘em. Spose tie it to buoy, drop ovehbo’d at pier befo’ inspection man come. Fellas come back in skiff for find it. Okay, down by Frisco dock. But spose big wind come, waves push, ev’ting drift like yest’dy. Bym bye lost, shrimp net find.” He chuckled, amused by the deductive process.

Pastorino stared in fascination. A hundred grand, there! Maybe two hundred; maybe twice that, even. His jaw thrust out. “Joe! What you wait for? Get by the phone! Call sheriff deputy!”

Young Joe stood hesitating; the eyes of the three remained fixed on the crystalline powder. A lot of money, all right. And who couldn’t use it? Running a fish camp and boat ways, even a dilapidated, peanut-sized operation like Riggs Cove, absorbed cash as sand takes rain. Pots, nets, Manila line, engines, renovating cabins — there was never an end to it. Lao Hsiao’s meager catch didn’t go into fancy cans anymore; when dried, it went into a crude grinder in the shed and was sold for feed for inland trout farms. Juho Kekkonen, the beached square-rigger Finn who built fine boats, sold his trollers one by one down at the city wharves, but he didn’t have a production line because he was an old-country craftsman who smelled of oak and salt, and lived by stem principles. Joe Pastorino catered to occasional sports fishermen and duck hunters who wandered in by chance, renting out the abandoned shanties and the half-dozen skiffs, selling the fine-cooked sea food.

“Joe!”

“Okay,” Young Joe said finally, feeling his father’s glittering eyes upon him. “I’ll call the law.” The Hsiaos and Pastorinos and Kekkonens, of Riggs Cove, didn’t live by peddling poison. He glanced out of the café window along the shore toward the Finn’s cabin. A battered little car was parked beside it.” Katty’s up from the city to visit her pa,” he added, his face lighting up with a sudden inner glow.

“Comes home every weekend after her office job,” Pastorino said impatiently. He watched Lao Hsiao put the packet back in his oilskins. The Old One, people called the fisherman. He’d been around longer than anybody could remember, since before the shrimp boom days.

“Somebody coming,” Young Joe said, still at the window.

A car skidded to a halt at water’s edge. Three figures in belted coats got out. Pastorino glanced out, stirred the chowder pot, bent to put another carton of beer in his icebox. The three men entered and sat down at the counter.

The proprietor’s keen eye told him they were not here to troll for bass or uncoil in the sun on the warm shingle. Each year a few more harried townsmen found their way to the cove, people hunting brief sanctuary from crowds and noise and rush; they stayed for an hour or a week. Young Joe and Katty Kekkonen had their dreams for such escapists: more cabins, more boats, more services, maybe a duck club for autumn hunters. But these three feral men sitting at the counter now were not sportsmen.

They wanted beer, and drank it silently, looking around with their agate eyes and missing nothing. One was older, with a thickened, raddled face. One was younger, with a sharp nose and a tic, and Pastorino’s experience told him by the walk and the clothes and the hands that this was some sort of seagoing man. The third was a person of Lao Hsiao’s own inexpressive race; he had a broad glistening countenance in which the eyes and nose were flattened, and gold fillings in his teeth, and pointed shoes off Grant Avenue.

The older one spoke to the younger one, who went outside and down to the wharf and looked closely at the shrimp boat, and then came back. Pastorino stirred the chowder while they mumbled, noting that his son had not left his place beside the window to use the phone, noting that Old Hsiao was sitting motionless in a dim corner, noting also that the giant Juho Kekkonen, master boat builder and retired blue water hand, and his trim daughter, Katty, were walking toward the café for the evening meal. That made every resident of Riggs Cove present and accounted for. Pastorino absently jiggled a clam knife on his palm.

“Who’s the guy runs the fish boat down there?” the ruddy one suddenly asked, and the cook turned.

“Old fella lives around here,” he said softly.

“Like to see him. Like to hire out the boat for a fishing party.”

“He ain’t got a license for parties. Just fishes shrimp.”

“Shrimp,” the man said. “That’s a good one.” He didn’t laugh. “Okay, we’ll buy some shrimp. Where’s he at?”

The Finn and Katty entered the restaurant. The Pastorino — Young Joe particularly — never failed to marvel that this oversized patriarch with the shaggy white thatch and faded blue eyes had produced so tiny and perfect a gem as the fair-haired Katty. Her heels tapped cheerfully into the room, she slid onto a stool and opened her jacket, turning her gay little-cat face toward Young Joe in a smile of unaffected warmth. Juho sat down like a folding monolith beside her, his glance resting gravely on the three visitors.

“Come on, quit stalling!” the sharp-nosed one said to Pastorino. His restless eyes had been darting about the café like a hungry ferret. “Any of these guys the fisherman?”

“All fishermen,” Pastorino said, after the moment of stillness. “Fish Mediterranean, Baltic, Pacific — “

The nosy man’s twitch increased.

“Which one was out on that boat today? We seen that boat from shore through glasses. Saw it come in this way after the fog. Who runs it?”

His voice was harsh, forced up a rigid throat. His two companions sat still, watching Pastorino.

“Listen,” the proprietor of the grill said, the clam knife still jiggling in his hand. “Listen — “

“I got boat,” Lao Hsiao said from his comer.

They swung around on the stools like a brother act to look at him. He sat quietly, smoking a cigarette, and met their intense gaze.

“A Chinaman,” the old one said. He flicked a glance at his flat-faced friend.

“Whada you know!”

The Asiatic member of the visiting trio nodded. “Might have guessed it,” he said matter-of-factly. “Thought there was something familiar about the cut of that boat through the glasses. Don’t know what; maybe a touch of junk in it.”

Everyone knew what he meant, except perhaps the raddled man. Lao Hsiao’s craft was seaworthy, but of mongrel line. He was not a disciple of progress. He found his depths with a lead line, sampling the bay floor and reading the sand and mud of the bottom like a chart, drifting with tide and current over cold subsea valleys and pastures to harvest the unpredictable myriads of shrimp. He was by inheritance a junk master.

The sharp-nosed one stood up. “Where’s that yellow buoy you picked up this afternoon?” he asked Lao Hsiao, and there was the thin tension of the tortured victim in his demand.

The others — the obvious drug runner from Chinatown and the nondescript receiver who drank beer thirstily — might want return of the floating package for expected profits, but the thin seaman wanted it for itself alone. When the Old One did not reply, he stepped forward with a jerk.

“Cough it up, old man!” he grated. “You got it. I knew, when the storm blew it away from the dock and into the stream, that it’d drift up the bay with making tide. I spotted it at noon with glasses from the shore road, moving north. Lost it in the fog, found it again, lost it. When I located it again, you was there with your net. Don’t give me that dead eye! Talk up fast!” He thrust his hand into the pocket of his coat.

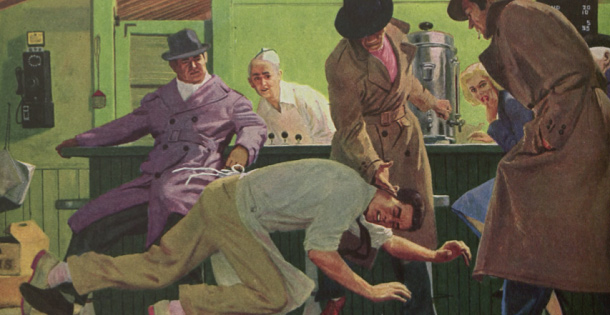

Young Joe, half crouching by the window, waited no longer. He sprang, as he had been taught to spring on combat patrols. But his jump was anticipated. The blotchy man stuck out a foot and tripped him. As he fell forward, the moon-faced runner leaned down and clipped him smartly behind the ear with the hard edge of his hand. Young Joe landed with a crash, shuddered, lay still. Katty screamed wildly.

“Shut up!” the thin one yelled at her in fury, shaken by the shrill cry. “Shut up, you! You want trouble too?”

She clutched the stool on which she sat beside her father, her slippers barely touching the floor, and was silent, so white that her lips were a crimson splash, her blue eyes enormous with horror.

But Juho Kekkonen, who had sailed before the mast in every sea on earth and had bucked hard oceans and hardmen all his life, was not shutting up on orders from a shriveled little junky. He had been unmoved and quiet until now, watching and listening, his pipe cold on the counter. When Young Joe went down he kept his iron control. But when the skinny fellow shouted and gestured a threat at Katty, the Finn rose with a roar that shook Pastorino’s Grill, and started, like a lumbering bear, to encompass his enemy.

The unstrung seaman shot him, his stubby gun firing through the pocket of his coat. The bullet spun Kekkonen about and slammed him against the counter. He stumbled over a stool and went to the floor. Katty caught the rolling head before it could strike the deck, and eased him down. She made no loud sound this time. She crooned over him, wrestling his heavy wool sweater down off his shoulder and arm to expose the ugly hole drilled by the shot through her father’s mighty biceps. She ripped linen from the sleeve of her own blouse, bound the spouting wound, ran to the counter for a towel to cover the scarlet bandage. She did not look at the gunman, who stood watching guardedly.

“Nice going, Harry,” the raddled man said with mild sarcasm. “Hollering and shooting is great on a quiet night in the sticks. If the law in that little burg along the road a ways don’t hear you, the Feds clear down in ‘Frisco will.”

“He was looking for it,” Harry said bitterly. He picked at the blackened hole in his coat, apparently more concerned about the damage to his garment than to the big buttinsky lying on the floor with the dame hanging over him. He turned back to Lao Hsiao, who had remained placidly where he was.

“All right,” he said. “You savvy Chinaman lingo, huh? . . . Charlie, you tell him so he’ll get it straight.”

He spoke to the Cantonese on the counter stool. The dapper runner stood up and approached Old Hsiao. He used a clacking tongue. Hsiao looked bland, shrugged, replied with a short phrase. It was answered sharply. It was not the sort of conversation anyone else in the room could follow. And suddenly the raddled man lunged to his feet for the first time. It had dawned on him that he and the thin one were the only persons listening, since the dame and her old man didn’t count now, and the young punk was out cold on the floor.

“Hey!” he growled. “Where’s that damn cook? Where’s that wop behind the counter?”

There was no immediate answer to that. Joe Pastorino, Sr., had vanished into the kitchen, and from the kitchen into the night. No one had noticed him depart. But he was most definitely gone.

“Took off to call the cops!” the thin seaman said, shivering like a fiddle string. “Probably a mile down the road by now, looking for a phone. They’ll be all over this joint in half an hour, maybe less.”

His lips were drawn back in a trembling snarl, and he whirled toward Lao Hsiao. But the Grant Avenue boulevardier — the man who looked like a pasty waiter with a night off from a chop-suey house — gestured him away. He reached out a hand wordlessly, and the Old One laid the package in it.

“This shrimper knows what’s good for him,” Charlie said in his phlegmatic voice.

“He seen the light, that’s all,” the ruddy one snapped. “Now listen, both of you. We got in here by car, but we can’t get out that way. They’ll block the roads first thing.” He paused, musing, and took a long draught of beer. “Harry, you get on that wall phone over there and call Corey downtown. You don’t need to gabble much; he’ll get it. He ought to be back by now from hunting around the docks in that cruiser he’s always yammering about. Just tell him to run that speedboat up here with his tail in the air. Fast, you understand? He knows the lay of the bay good enough. Tell him near Riggs Cove, meet us on the water off that rocky headland just south of this place where we seen the fish boat today from the road. You know?”

“Roqueno Point,” Lao Hsiao said unexpectedly. They looked at him, startled and uncertain.

“Yeah, that’s it,” the thin one called Harry said. “Seen it on the map. He ain’t kidding, Ed.”

“Okay,” said the boss man, after a moment’s hesitation. “Roqueno Point. Tell Corey meet us off that soon as he can, and it better be quick. We’ll be in this guy’s boat, tell him.”

“Taking a chance using the phone,” jumpy Harry said.

“Better than running a roadblock,” Ed said. “Only way out.” He glanced at old Kekkonen, groaning beside the counter, and at the bent back of the girl, and then up at the Cantonese. “Charlie, walk that boatman down the wharf to his tub and get ‘er turning over. Except for that slob who beat it, we got to take everybody along, so they don’t tell where we went or how. We’ll leave ‘em on the fish boat when we transfer to Corey’s launch, that’s all. We’ll be home time they get back here. Never mind the car; it’s somebody else’s anyhow.”

Harry got busy on the telephone. His end of the conversation was casual, also as cautious as the emergency permitted. But obviously the speedboat enthusiast called Corey was an intelligent mariner. Right! Roqueno Point, swathing fog or sparkling clear.

But Lao Hsiao, trudging stolidly down the wharf in front of his vigilant countryman, saw that the fog was lifting gradually. Keeping rendezvous with a launch off the point would offer little difficulty. Aboard the boat, he started the engine and they waited in patience to cast off. Both were reticent types.

In Pastorino’s Grill, Juho Kekkonen was sitting up while Katty put final touches to his bandaged arm, and Young Joe was stirring painfully. Ed kicked him into dazed wakefulness and bound his hands behind him with Joe’s own belt, hoisting him to his feet.

“No funny business, kid,” Ed warned as he lurched. “You got sense yet or do I knock some more into you?”

Joe ignored him, staring at Kekkonen’s arm. He recognized the marks of violence, but did not recall the act. He walked unsteadily to Katty, but the strap restrained him from taking her in his arms.

“You all right, honey?” he asked.

“I’m all right, Joe,” she said, trying to smile. “Just be easy. Pop’s doing fine, even if he doesn’t look it.”

Joe asked no more questions, but pressed his face down against Katty’s and kissed her. “Don’t let these bums scare you,” he advised. “They just act tough.” But he felt no conviction. Ed motioned them out toward the wharf.

As they stumbled along it to the boat, Katty hurriedly whispered the details to Joe. He nodded, reserving his doubts about big Ed’s intentions. These were treacherous and savage people, by the nature of their work, and taking hostages on this weird voyage was not reassuring.

The lines were dropped, the engine thudded and the craft swung, gliding out of the cove. Lao Hsiao was at the wheel and Charlie at his elbow. A thin rain swept over the ridge and swallowed the shoreline. They seemed very alone. But as the brief squall passed, they could see the tip of Roqueno Point rising in starlight to the south, a rock-studded crest crowned with cypress twisted and stunted by gales from the sea. All this that lay before them was Lao Hsiao’s happy hunting ground.

The prisoners sat on a hatch, Ed stood guard, and Harry prowled the boat for weapons. He found nothing, then went forward into the bow to keep a lookout across the shimmering bay. The visibility improved, and their captors kept a close watch on the shore road for moving lights.

Lao Hsiao looked back from the door by the wheel. He cast a reflective eye over his draped net on the boom, saw that Kekkonen had recovered his mobility, and suggested mildly that the net be folded properly in its place before it fell overboard.

Kekkonen considered. He and Old Hsiao and Pastorino the elder, those three were more at home on water than on land. Because they were old now, they lived ashore together. The long voyages were over; they were beached in Riggs Cove by an accidental but fortunate joining of far-flowing currents from the earth’s ends. They understood one another. The Finn began to arrange the net, working slowly with one arm, ignoring big Ed. The nets lay across the boom so that they would slide smoothly over the stem when the retaining line was loosened. Precision was needed in such maneuvers.

They were approaching the rendezvous. Harry came aft.

“Hey, Ed,” the seaman said,” I forgot there’s an ebb tide. She’s running out fast and this is shallow water. There’s a hell of a big mud flat off there, sticking out from the point.”

“Stop worrying,” Ed told him. “This Chinaman ain’t going to run himself aground, and Corey knows his business.”

He broke off, gaze fixed ahead. Idling over the easy swells was the vague loom of the launch, slipping along the side of a mist curtain, a shark shape gleaming faintly in the dim light. It moved to intercept their course. The figure in the open cockpit hailed. It was the obedient Corey, on the dot. With the shrimper slowing at the edge of the flats, the boats drifted together, a line was flung and caught.

“You okay, Ed?” Corey asked, his voice muffled. Ed said he was. Everybody and everything was okay, he said. Get the hell aboard the launch, he told Charlie and Harry, and then they would get going. He looked at Joe.

“We’ll take the young lady along with us as far as town,” he said,” just in case you got any bright ideas or maybe somebody tries to cut us off. Keep your shirt on and she’ll be home on the bus in the morning.”

Joe started for him with his hands still fastened behind, and all Ed had to do was give him a hard push, tumbling him over the hatch. Joe got to his feet with difficulty.

“I’m not afraid, Joe,” Katty said. “I’ll go. It’s better than everybody getting hurt or something, isn’t it?”

They lowered her over the gunwale into the launch; Corey steadied her, and Ed and Harry piled down after her. Charlie went last, clutching the waterproof package. He had barely gone over the side when Kekkonen began working on Joe’s bonds, setting him free, and Joe stood rubbing his chafed wrists, seething with his inability to retaliate. The boats had come together facing bow to stem, and as Corey flipped off the holding line and reached for his instruments, Juho Kekkonen pulled the retaining knot on the shrimp net. He acted on an order, unspoken but quite clear to him, from Lao Hsiao.

The net slipped unobtrusively into the sea, trailing out behind on the warp without a splash. Instead of sinking to the bottom, it was drawn along just under the surface, following like a long and tangled tail on its cork floats.

The shrimper’s engine began its laborious grinding again, and the bow swung slowly under rudder pressure. Lao Hsiao peered back, saw the position of his net, and smiled. Alongside them, the launch roared suddenly into life, moving out into a headlong dash toward the safety of the distant city.

The Old One’s boat picked up speed, describing a wide arc that cut across the course of the launch. He passed before its bow and it began to knife under his own stem on a fast tangent. He straightened out, pushed the engine up a notch, and waited.

Things abruptly began to happen to the receding launch. Like a surprised bass that has taken a lure and heads for cover, it was snapped around, throwing all five figures in the cockpit off their feet. It swung crazily, jerking like a maddened pendulum. And then, as if the bass were hooked by the tail instead of the mouth, it fell into line behind the shrimp boat and followed, drawn stern first. There was a furious boiling of white water under its yawing counter as the propeller, thoroughly fouled in the big trailing net that had been dragged beneath its keel and into the rotating blades, fought vainly to bite into the current.

Kekkonen let go a fierce yell, Joe began to grin, but Lao Hsiao was too intent on finishing the job to reveal his own sentiments. And as he spun the wheel again, glass shattered in the window beside his head. He heard the shot, fired from the reeling launch, and once more revolved the wheel, glancing over his shoulder. Kekkonen and Joe had flattened to the deck, and Hsiao saw chips dancing off the hatch cover where more bullets ricocheted. The twitchy seaman forty yards astern continued to fire until his clip was empty. Clinging desperately to the bucking craft, he could still lunge to the sway, and trigger the gun. But the shrimper never gave him a steady moment to aim.

Joe pointed toward the mud flat. Beyond the ripples of milky water where the brown bank slanted there stood a square of rushes, a blind he had built the autumn before for duck hunters. It was only a dim wraith, etched in star shine.

“Got a shotgun cached in there!” he yelled, and slithered overboard, striking out for the flat. Kekkonen stared, recalling vaguely that Joe kept a gun concealed in the blind protected by a waterproof box. The closed seasons never cramped his instincts.

Playing the struggling launch on the strong and heavy trawl lines, the Old One hauled it inshore while the speedboat propeller ceased all protest, so enmeshed had it become in the tough strong net that wound and bound the shaft. The nosy gunman was trying to reload and keep his feet, a complex and apparently impossible performance. And holding the momentum he had gained, Old Hsiao swung his boat again.

Like the writhing tip of a whip that is cracked, the launch tore sideways through shoaling water, flung far out of the shrimper’s wake, and lifted on a frothing swell. It struck the slope of the mud hank with a soft crunch and slid up it, coming to rest high but not dry in the ooze so recently left by the dropping tide. It lay canted over on its beam, dragging a deep furrow through the mud on the end of the straining trawl warp and broken net. Kekkonen stepped aft and, with several blows of a hatchet kept handy there, severed the thick line and cut it free.

Lao Hsiao circled his churning boat again, keeping just out of range, and cruised along the bank to inspect his handiwork. It was inspiring. The four seagoing gentlemen had been snapped violently out of the launch to plow their own individual furrows in the slime. Katty, however, was not with them. She had slipped overboard just before the launch struck, and was now wading cautiously ashore in the direction of the duck blind. Young Joe had already landed and reached the little shelter, and presently she climbed in with him among the tules.

The runners of dope were now running for their freedom, but it was an arduous journey. They scrambled to their feet, attempting to dash across the open expanse toward cover of the rocky point. The mud was not bottomless, neither was it solid, and they sank in it to their knees. They sprawled and wallowed and floundered up. Their anguished cries echoed over the bay.

This route took them within a few yards of the blind. Young Joe rose from his ambush, hailing them, and when they responded to his challenge by veering off in panic, he let them have both barrels with light birdshot. He reloaded and fired rapidly again. Katty stood up beside him, pointing. Pinpricks of light were twinkling along the shore road behind the point, slowing and turning beach ward to the reverberating blasts of the gun. Old Joe’s dash for the law had not been wasted.

The fugitives halted, hands in air, and the haggard man threw his gun far out into the mud. Katty went carefully forward to relieve the tortured quartet of other possible weapons. They stood wriggling ponderously, unable to rub burning portions of stung anatomy, while she frisked them.

Lao Hsiao nodded complacently at Juho and set his boat on a heading for Riggs Cove. Young Joe and Katty had begun to march their bag through the flats toward shore, and dim figures of a posse were already running out from the road.

The official reports and examination of the package did not end until midnight. But eventually the swarms of highway patrolmen and sheriff’s people ceased their buzzing and left Pastorino’s Grill, taking with them the mud clogged prisoners. Old Joe fired up the stove once more and set out the beer. Katty admired the new bandage the police doctor had put on her father’s arm, and sought to console Young Joe for his aching neck.

“You heard what they were saying about the rewards?” the excited young man said. “You know what that can do for us?”

“What?” Katty demanded, enraptured.

“Get a new boathouse for Juho. Fix up this restaurant. Remodel the cabins. Get new rental skiffs. Put Riggs Cove back in business as a going resort. That’s what.”

Kekkonen stirred, waving his pipe stem. “Buy Ole Shoe new shrimp net,” he said solemnly. “Net costs a lot.”

“With that,” Old Joe declared,” he can buy a new boat.”

Lao Hsiao sat in his corner and smiled blandly. “Got plenty money for buy boat. Don’ want. Old boat damn good. Got money in bank, save long time. Spose Gov’mint money ain’t so much. What you want, Joe? T ‘ousand? Two, free t’ousand dolluh? Okay, Joe, you fix up joint good. Lotsa people read newspapuh, come this side bymbye for see, stay for fish. You an’ Katty fix ‘er all up, huh? You an’ Katty, Joe.”

They stared at him. It had been an unprecedented outflowing of words for silent Lao Hsiao. And they were stunned by the disclosure of such wealth, amassed unbeknown in their midst. Even the verbose Pastorinos could think of nothing adequate to say.

After all, they reflected, they knew very little about the quiet little Asian with whom they had lived so peacefully and for so long. His race’s repute for secrecy and inscrutability crowded their thoughts, and they looked at him shyly, as at one suddenly set apart from them, where, before, he had been just another of the aging fishermen, a sturdy friend taken for granted.

The Old One grinned. “Hyiiee! Lotsa damn fun spend money sometime. Save too long. Us ole fellas, we don’ know bout fun spending money no more. Joe an’ his Katty show!”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now