She hadn’t meant to be a thief. But then none of us do, and all of us are, stealing time and taxes and other people’s laughter, if nothing worse. Thieves. For “What is mine is mine and what is thine is mine” wasn’t written of angels, but of men. And women. And children.

It began with her growing up. For seven is grown up when all you’ve been before is six or five or even four. So she was grown up more than she’d ever been, and she was wondering about things, and wanting things, not toys that any dime might buy, but things unseen, unknown, like grownups want. She wanted to know who she was, for how can you grow up to be someone you don’t know? All she was the little girl in the third bed from the fire door, a little girl in the looking glass. And that isn’t enough to be. But it was all she was, for herself was the only family she knew.

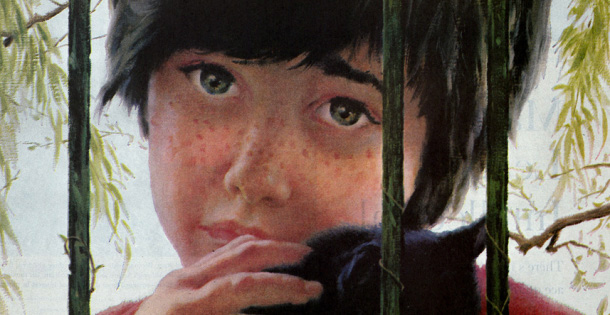

Laurie went to the washstand and looked at the little girl in the looking glass. She had big, green eyes and black, black hair; there wasn’t any curl to it, but it had a shine like shoes on Sunday. She knew her eyes would be green always, and her hair black and straight, but her face was the face of a stranger. She couldn’t see the lady in it that she was going to grow to be. She pounded on the glass with her fists. She said, “Who are you? Are you pretty or ugly, fat or thin? Don’t you love your little girl, or are you sick or lost? Why can’t I know you? For I want to, I want to belong to you!”

But the little girl in the looking glass only pounded back with her fists that were as cold and hard and senseless as glass.

And Laurie knew she couldn’t wait another day, and she ran to ask Miss Hanacher about her mother. For Miss Hanacher would have to answer her now that she was old. She couldn’t say, as she had before, that Laurie was too little to understand. For Laurie knew about being poor, and sick, and lost; she was as old as that. So Miss Hanacher would have to say if Laurie’s mamma was too poor or too sick. That was what most of the mothers were. They had to work, or they had to lie in hospitals, so their children lived in The Home until they got well or rich, except those who belonged to someone called The Court. But whatever it was, the children knew whom they belonged to. And Miss Hanacher knew, for she was head of The Home and knew everything about everyone.

The big girls said you couldn’t have the smallest secret without Miss Hanacher’s finding it out. It seemed that she could look right through you with the gray sharpness of her eyes — and if she couldn’t see the secret, she could smell it with the sharpness of her nose that was so pinched it was like a finger pointing. Miss Hanacher looked like a witch, and she wasn’t anybody’s mother. She was just bells to tell you what to do, and rules to tell you what not to do, and she discovered secrets. And this day she told a lie.

She looked at Laurie looking at her, and said, “Laurie, your mother is dead.”

Laurie knew it was a lie. She pounded on Miss Hanacher. “Why do you keep me from her? All the other little girls have mothers! Why can’t I have mine?”

“Oh, Laurie!” Miss Hanacher tried to take Laurie in her arms. She said, “You’re not old enough to understand how things can’t always be the way we want them. But if I could give you your mother, I would!”

Which was the worst lie of all. For Laurie knew Miss Hanacher knew where her mother was. She was in the filing cabinets. Laurie looked over Miss Hanacher’s shoulder at the rows and rows, a whole wall of little tin drawers. That was where the mothers were kept, and the fathers too. There were all the words in there that it took to make a mother and father. And Laurie said to Miss Hanacher, “No!” And it was hate.

It was so quick and deep a hate; it was as though it came natural to her. Miss Hanacher shivered, and Laurie twisted free and ran out the door and out of The Home and across the lawn to where the weeds began about a troubled little path leading into the willow forest that was only two trees big. But they were so great their branches swept the ground, and inside you couldn’t see from their beginning to their ending, so surely it was a forest. It was a dark and secret place, where the children always came to hide when they were hurt.

Miss Hanacher went to the window and watched as Laurie disappeared beneath the trees. She said, “I must learn to lie better.”

Laurie didn’t cry very long. For she knew what she was going to do. The only trouble was, she couldn’t read. So she sat on the edge of the willow forest and watched the big girls walking by to see if any carried a book too small and thick to be a picture book. For today was Saturday, and if someone carried a reading book when they didn’t have to, it must be because they could read real good. By and by Gladys came with a book.

Gladys was ten, and she was here because her mother was sick in the hospital, but in two years they said her mother would be well, and Gladys could go home. Gladys was matter-of-fact. She said, “Of course I can read. I’m ten.”

“Can you read the big words like `mother’ and street numbers?”

“Of course I can, stupid.”

“Can you keep a secret?” Gladys looked interested. “From whom?”

“From everybody.”

“That can’t be done. Miss Hanacher would find out.”

“Would you tell her?”

“No.”

“Then how would she find out?”

“Because she always does.”

“Who says so? You only know about the secrets she’s found out about; you don’t know the secrets that are so secret she hasn’t found out. I have secrets she hasn’t found out.”

“You have?” Gladys sat down in the lace of leaves. “What are they?”

“Cross your heart and hope to die and never visit the moon if you tell?”

Gladys crossed her heart and hoped to die and never visit the moon.

“I have the secret that I want to know who I am, and I’m going to. I have the secret that every night when Miss Hanacher takes her bath she lays her keys on the bed table, and I’m going to take them and look in the filing cabinet where the mothers are and find out who I am.”

Gladys was aghast. “You’d be skinned alive!”

“Why? My mother is mine, isn’t she? I have a right to her, don’t I? I’m her little girl!”

“But the keys are Miss Hanacher’s!”

“She won’t know. She takes long baths, and it won’t take you long to read my mother’s name and address.”

“Me?”

“Sure. That’s why I’m telling you!”

Gladys rocked back and forth and thought about that. She was bored and homesick, and it would be fun to have a secret; but the best would be fooling Miss Hanacher. For how could she find out, for ladies in the bathroom always closed the door.

“When do you want to do it?”

“Tonight; she takes her longest baths on Saturday. You wait by the cabinets. Do you think you can find me in them?”

“Of course, stupid, you’ll be under L.”

“Why?”

“For Laurie, that’s why. And if we get caught, I’ll kill you.” Gladys got up and walked away. She didn’t want her friends to see her with someone only seven.

Laurie was first in bed that night. Miss Hanacher noticed that, for she always came to say good night to everyone. She kissed Laurie to see if she had fever, but all she had was eyes — they sparkled and looked everywhere but at Miss Hanacher. They were the eyes of a little girl with a delicious secret, and Miss Hanacher was so pleased she kissed her again. That was the wonder of being only seven; yesterday’s tears truly belonged to yesterday. Miss Hanacher tucked every one of the twenty little beds and turned out the lights, and by and by she said good night to the big girls, and all The Home settled down dark and still. Only Miss Hanacher couldn’t settle down; she couldn’t forget Laurie’s eyes — the ones when she said, “No!” and the ones she took to bed with her. Maybe a nice hot bath would help.

Miss Hanacher laid her keys on her night table, just so they covered the crack in the marble, like she always did, and tested her flashlight. Then she got her slippers and gown and robe and a new book on child psychology that was supposed to answer any problem in only 560 pages, and she went into the bathroom and closed the door.

Laurie heard the door shut. She had had to pinch herself so many times to keep from falling asleep that she just about hurt all over. But she was awake, and she heard the door and the water running like a train going down a hill and then the swishing like a storm. Then she hardly dared breathe as she slipped down the hall and into Miss Hanacher’s bedroom, where she nearly died of fright. As thieves often do. For there wasn’t any noise in the tub. She almost turned and ran, but first she peeked through the keyhole, and Miss Hanacher was reading a book, which was a very odd thing to do in a tub, but it was a fine thing, for it was a very big book. Only suddenly Miss Hanacher looked around, as if sniffing the air for secrets. Laurie closed her eyes and held her breath, and in’a moment she heard the soft swish of water as Miss Hanacher went back to reading. Laurie tiptoed to the table and got the keys and flashlight, and made sure the watchman wasn’t coming; then she ran to Miss Hanacher’s office. Gladys was waiting by the cabinets.

“Well, it’s about time! Did you get the keys?”

Laurie held them out.

Gladys was a little scared, but this was the first excitement that had happened since her mother had gone to the hospital.

Besides, it really wasn’t stealing, for the little individual drawer, or box, had Laurie’s name on it, and if your name was on a thing, surely that made it yours — really yours.

The sixth key opened it. Laurie snatched it right out of Gladys’s hands. “It’s mine!” She pulled the little drawer out, and sat down on the floor and laid it in her lap, carefully, carefully, as though it weren’t made of tin but glass and would break. And Gladys knelt and held the light on the box as though that were the only thing in the world that mattered, just the box and the glow it laid upon their faces, for the inside of the box was white. It was goods. Laurie picked it up; it was a baby’s slip. And on each shoulder was a little pin with four pretend pearls.

Laurie counted each one out, they were little drops of loveliness in her fingers; her hands moved so gently around them, for they were the first things she had ever known that her mother had known. For this was such a little slip it must be her mother who had pinned it on her, for she couldn’t have been old enough to know anyone else.

Laurie said, “A mother would have to love her baby very much to buy such fine pins.”

And Gladys said yes. “I’ve seen them in the five-and-dime; you only get two for twenty cents, while the regular ones are thirty for fifteen cents.”

“She must be a pretty lady to love pretty things.” And suddenly the little girl in the looking glass wasn’t a stranger. She was pretty like her mother, with pearls on everything.

Laurie looked to see what else was hers. The next white was a diaper with two pink diaper pins pinned in it. And underneath the diaper was stiff paper, and she was so excited she just sat looking at it for a moment, for it was on paper that writing would be.

She touched it, and it made a little crackling sound, a sort of angry sound, as if it were something that mustn’t be touched.

But Laurie picked it up and unfolded it until it became a shopping bag, and she stuck her head inside to see if there was anything in there. There wasn’t. On the outside there was printing. And slashed beneath in black letters were the words, NOBODY BUT NOBODY. Gladys read them out, then she read the paper that had been under the shopping bag in the very bottom of the drawer.

July 23, 1953. Infant, female, Caucasian, about three days old, weight 6 pounds 3 ounces, found abandoned in a shopping bag against the N.E. lamppost of 37 Street and Park at 3 :20 A.M. The baby wore a white lawn slip with two shoulder pins of imitation pearls and a white diaper with pink diaper pins. There was no note or identification. Officer Logan gave the report. On admission to the hospital the child was listed as No. 1376421. On admission to The Home she was named Laurie.

Gladys read it very slowly, for some of the words were strange, but she knew what they said. She had read The Little Prince, and she knew what the word “abandoned” meant.

“What does it mean?” Laurie beat on her arm. “What does it say about my mother and father?”

“It doesn’t. They aren’t here. They didn’t tell on themselves at all. They only threw you away. That’s what ‘abandoned’ means, something you don’t want and you throw it away like trash. You were put in a bag like trash too. I guess this one, and that’s why it’s here.” She stuck her head in to see how it was for size. “You were left in the street against a lamppost, and your mother and father didn’t put their names on you, for if they’d wanted you back, they wouldn’t have thrown you away.” Gladys was fascinated by the thought; she kept saying it over and over in different ways and looking at Laurie. This was the biggest secret ever.

Gladys fingered the slip, “There isn’t any lace on it, so your mother must have been very poor. I guess that’s why she threw you away. My baby things have lace and embroideries.”

Laurie’s lips were trembling so she couldn’t speak. She pointed to the bag, to the printing on the outside that she wouldn’t believe didn’t belong to her.

Gladys said no. That was the name of a store. Her mother had taken her there once when she was little to see Santa Claus. And NOBODY BUT NOBODY wasn’t a mother, it meant — Gladys looked at Laurie, and all of a sudden she didn’t see trash or even a secret. For the first time she saw a little girl who had wanted to know her mother, and knew her mother had thrown her away. And Gladys didn’t know what to do about it. But then, Miss Hanacher hadn’t known what to do about it either.

She stood there now in the doorway watching the darkness of the room, and the darkness of truth. For she had got there too late to stop the reading of the note, and what is read can’t be unread. The flashlight lay on the floor and made a small slash of white in the night. It made ghosts of two little girls; one who didn’t know what to do, just sat there hiding her mouth with her hands and staring terrified at Laurie; one who didn’t do anything, just sat there with the tears running down her cheeks and making no sound at all. Miss Hanacher wanted to take her in her arms and tell her it was all right, but those weren’t words you could tell to thieves in the night, or even to broken hearts.

Infinitely slowly Miss Hanacher moved back and away and out of her door. She tiptoed to her bathroom, and set up a great sloshing in the tub, for she was the one who discovered the secrets and told the lies. And after a little while, when she peeked and saw the keys back on her table, she came out and listened to the crying of the little girl who was the third bed from the fire door, a girl in a looking glass and a little girl who had been thrown away. And that was too much to know.

Miss Hanacher waited until the crying stopped. Then she went and held Laurie in her arms, not tight enough to waken her, but maybe enough so she would know in some secret place inside that there had been arms around her. And Miss Hanacher thought and thought. How could you tell a little girl who knew she had been thrown away that that was a good thing to be? How could you make a lie as big as that sound true?

Miss Hanacher laid Laurie in bed, and went and pulled the blind so the streetlamp light couldn’t touch her. Then she went to her room and threw the book she had been reading into the tub and drowned it, as if it were alive and could feel and be dead. Then she cried herself to sleep, for she really was too young to have seventy children, and she was sure she was not wise enough.

Laurie had fever the next day. Miss Hanacher said she guessed it was a cold coming, but not a bad one, so she didn’t make Laurie go to the infirmary, she only made her put on a sweater and told her to stay all day in the sun and drink lots of warm milk and cold juice, and she kept sending them out to her all day and the day after. Laurie didn’t say she had fever only because she cried so much. She couldn’t tell about the tears without telling the why, and she wouldn’t tell that. Not even to Gladys would she ever tell it again. Not the word “mother.” For she hated it. Hated it as much as her mother must have hated her. That was the lady in the looking glass. Hate.

And Laurie hated street lamps. Everywhere she looked she saw them, for The Home was a block square, and all around it were the lamps. Before she had thought of them as lollipops, but now she saw them as watching eyes watching her, because they knew who she was. She ran into the willow forest to hide.

That is how it happened that it was Laurie who found the kittens, because all the other children were in school. She found them in a nest of leaves, three black babies without even their eyes open, but their mouths wide and pink and yelling, with the tiniest, sharpest prickles of white teeth and real whiskers all around. Laurie knelt and was afraid even to touch them. But she did, and the baby hissed! A lion hiss just half a kitten big. It was so precious, so tiny and fierce and helpless. And all around it a great, strange world waited to pounce upon it, as worlds do on the very young.

Laurie poked the second kitten, and it hissed. She poked the third kitten, but it sniffed and grabbed her hand with all four paws and needle claws, and it sucked and sucked on her fingers, for it was the tiniest and the hungriest. Laurie had been drinking milk, and when Laurie drank milk it was sort of as if all of her were drinking it. Laurie dropped some on her hand; the drops ran down her fingers in rivers of milk, and the kittens screamed and tumbled and fought, and there were three little kittens sucking on three little fingers. Then the purring began, real cat purring just kitten size. It was like a song singing in the shadows. They sucked and sang and fell asleep, a pile of warm softness in the puddle of her lap.

Laurie waited most all day, but the mamma cat didn’t come for her babies, and on account of The Home dog running loose, Laurie didn’t dare leave them in the willow forest. And on account of their crying so much, for they were hungry all the time, she had to take them to bed with her, which was a warm and wonderful thing to do. Only the beds were just a table apart, and the children around heard them mewing, and they made such happy noises that Miss Hanacher came out of her room.

Everyone popped into bed, and Laurie curled about the kittens, which began to purr so loud she was sure Miss Hanacher would hear. Only Miss Hanacher had a handkerchief in her hand and was blowing her nose as she came in the door, and she saw twenty little girls lying stiff and still, and all looking at her with great, frightened eyes as though she were a witch or a man from outer space. Or as though they had a secret. Miss Hanacher blew her nose again and pulled the blinds.

“I think I’m getting a cold, so I’m not kissing anyone good night. Have you said your prayers?”

“Yes, Miss Hanacher!” It was a deafening chorus.

Miss Hanacher stopped by Laurie’s bed. “How do you feel, Laurie?”

Laurie was twisted in a knot, and her eyes were about to pop out of her head, and she talked very loud and quick. “I feel fine, Miss Hanacher, and I’m sleepy, I’m almost asleep already, and I said my prayers twice and drank all the milk, and I’ll just go to sleep now, thank you.”

Miss Hanacher looked as if she were going to burst, but she only choked and turned out the lights and went to her room and slammed the door. It was such a loud sound it had the whole building listening, and nineteen little girls popped out of bed to crawl on Laurie’s bed, and the kittens crawled over everybody’s toes and tasted a few. And one little girl, whose mother had worked so hard and long she was almost rich and could give her foolish things, ran and got her doll’s bottle that had a real rubber nipple with a hole in it, and they filled it with the milk Laurie hadn’t drunk but hid behind her bed, and the littlest kitten lay on its back and nursed it just like a drink-and-wet doll. They put doll diapers on it, and it even wet them, and the excitement was so great one of the big girls came to see, and she knew where there were two more bottles and diapers, and before morning the entire Home knew about the kittens in Laurie’s bed. And yet it was a secret!

For Miss Hanacher did have a cold. Her door never opened except to let the doctor in and great trays of warm milk and juice. And sometimes if you walked down the hall real slow you could hear sneezing, and sometimes coughing and blowing. And it was wonderful, for with her eyes watering like they must be, she couldn’t see secrets; and with her nose stopped up, she’ couldn’t smell them; and with her door closed and her inside, the whole Home was free. Because the housekeepers didn’t care about secrets, so long as you didn’t bother them.

So seventy little girls learned to know and love three little kittens. But the third day the biggest kitten died. It had opened one little blue eye, and it had tried to go around and see the world. It had walked the length of the dormitory where the cleaning woman had scrubbed; then it crawled into Laurie’s lap and washed its feet so it would be a clean kitty, as kittens like to be. But in just a little while a terrible pain seemed to come to it. and it screamed and twisted and then lay very still. Laurie was alone, for she hadn’t been sent back to classes yet, so she held the little one in her hands, trying to keep the cold that was coming from coming to it.

Then the cleaning woman came and said it was dead. She took Laurie and the kittens right into her lap and covered them with her apron, and said, “Honey, baby, The Home isn’t a place for kittens. We have to keep it clean. and we have to use the things the city sends us, for none of us are rich, and the cleaning things we use are fine for cleaning floors, but they can kill kittens if they wash them off their feet. I’ll tell you what, I’ve got a wooden box in my closet, and we’ll make a little house out in the yard for them! Yards is where kittens love most of all to be.”

“But the dog! What about the dog?”

“Oh, he’s a nice old dog; besides you can put him on leash, and with all of you girls watching, the kittens will be safe.”

Only they weren’t. For even with everyone watching a thing, sometimes someone forgets. The day after the day of the funeral of the first kitten, the second kitten lay torn and dead.

Laurie couldn’t stop crying. She cried so that the big girls got frightened and ran to get the nurse. All except Gladys, who once upon a time had shared a secret with Laurie. And she had thought about it a lot; she had even got up in the night to look out at the street lamp and see if there might be a shopping bag by it. But most of all she hadn’t told.

Gladys dug a quick hole and buried the kitten. She snatched the last one and stuffed it down her dress. She said, “It’s our secret.” And she disappeared in the shadows of the willow forest.

The nurse put Laurie to bed in her own bed and called the doctor, and the doctor gave her something to make her sleep. But first he asked for an extra blanket to make her warm; only all the blankets were being used, until the nurse remembered a new one brought into the supply room that very day, and she sent one of the girls for it. It was so new it still had the price tags and pins and was in a shopping bag. The nurse threw the tags and the bag in the wastebasket and pinned the pins in her collar. Then she spread the blanket; Laurie went to sleep.

It was past midnight when Laurie woke. She watched the fire-door light watching the night. She looked at the floor shining red as blood beneath it, and so clean it could kill. She sat up. What if Gladys hadn’t understood! Laurie ran down the hall and up the stairs, and she found Gladys asleep and the kitten wandering around the floor. Laurie snatched it and ran and washed its feet in the washstand. She all but drowned it washing it and all but choked it drying it. But she waited and waited, and it didn’t die. It only snuggled in the curve of her neck as if it knew it belonged there and was safe. And Laurie held it close and loved it with a heart that had waited seven years to belong to someone, and have someone belong to it. It was a fierce and powerful love, as loves that have been hurt can be. As loves that know they can’t be, are.

For Laurie knew it couldn’t be. That was why she had cried so. The moment she held the second dead kitten she knew there was no safe place in all her world for the little one that was left, the littlest one that had needed her more than any other. No matter how much she loved it, she couldn’t keep it safe. And the strangest stirring stirred within her as she thought that out, how love isn’t enough.

She would have to give the kitten away, but there wasn’t anyone to give it to. She didn’t know any grown person who could just keep a kitten because they wanted to but Miss Hanacher. But Miss Hanacher was the one who made the floors be so clean, and she was only rules and don’ts and filing cabinets.

Laurie sat very still as she thought of a tiny baby that had to be given away not because it wasn’t loved, but because there were worse hurts to come to it than being thrown away. But it was so small it would be lost in any dark. And she thought about that. She thought of a place where there wasn’t ever any night. She really didn’t think it all up on her own, for she was too young to do big things like that. She could only think of things she knew. But she knew about street lamps, how they watched the night, and about babies in shopping bags.

Laurie sat cross-legged on her bed and stared at the wastebasket where, thrown half in and out and upside down, there was a shopping bag. It was new and strong. Very slowly Laurie climbed down off her bed and got the bag. She folded her sweater in the bottom, put in a doll bottle of milk and ran out the fire door.

The night was so big and dark outside that Laurie was afraid to be in it. But it wasn’t as dark as the brightest day would be if the third kitten lay dead in her hand. She hugged it closer and ran across the grass to the gate she thought she would have to climb — only it was unlocked! So she slipped out to the street lamp, where the night was gone. She kissed the kitten, kissed it so hard its eyes opened, just little cracks that looked at her as though they wanted to remember how she was. Only just then there was noise. It was the watchman with his big feet and lantern, and he would find the fire door open! Laurie laid the kitten in the shopping bag and the shopping bag against the lamppost, and ran for the fire door. She didn’t see Miss Hanacher standing in her window. She didn’t hear her dial a number on the telephone and say one word. She said, “Now.”

But Laurie didn’t see or hear, she was crying so. She just ran down the dark of her room and raised the blind, and watched a shopping bag sitting by a lamppost in the middle of a night. And the strangest thing — in just a minute or so a young lady came walking down the street, even though it was so late. She was such a pretty lady, with curling hair and real high heels. She was walking so fast she would have walked by anything in the dark, but the light was so bright she stopped and looked and felt, and brought out a tiny black kitten. The lady was so surprised she laughed out loud. And she kissed it! There where anyone might see, she kissed it, and then she found the doll bottle and put it in the little mouth, and she said, “Oh, you precious, precious child!” She said it out loud, as though the night might be listening and like to hear. She let it nurse for a little, then she cuddled it in the sweater, where it would be warm and safe, and she walked on down the street and out of sight, slowly, as though the kitten slept.

Laurie was still standing there when Miss Hanacher came and put her arm around her. “Laurie, are you all right?”

Laurie said, “Oh, yes!” And she was. She could feel it inside, how all the hurt was gone, for she understood how things aren’t always what they seem. She looked at Miss Hanacher, who was so rosy and rested she didn’t look like she’d had a cold at all. She looked soft and pretty in the lamplight. Laurie said, “Miss Hanacher, could you leave the blind up, for with it up the light comes clear across to touch my bed, and I like to see it there.”

“Do you like street lamps too?” Miss Hanacher was so pleased that Laurie could tell she liked them, and, without half thinking, Laurie hugged her, and Miss Hanacher hugged her back and picked her up, even though she was so big, and carried her to bed. She pulled the new blanket close and said, “My, this is a lovely blanket! It’s soft as kitten’s ears. I think we’ll have to let you keep it for your very own.”

Laurie petted the blanket. She touched the satin border that was softly white, as pearls shining in the night, like pearls all around her. She watched Miss Hanacher tucking it about her, and she saw her mother pinning pearls on her baby shoulders because they were the nicest things she had. She could see her mother shining in that shining light, a lovely, sparkling someone holding back the night. Her mother who had loved her as much as that, to take her from the hurts that must have been and leave her where even as tiny a baby as she couldn’t ever be lost. Laurie lay there smiling, for it made such a pretty picture.

Miss Hanacher said, “Do you know, Laurie, you look lovely tonight. You’re going to grow up to be a very pretty girl.”

Laurie smiled and said, “Yes, I know. I’m going to grow up to be a lovely lady who loves her family.”

And Miss Hanacher said, “I’d like to be that too. I’d like it most of all.”

And they laughed. For they both knew Miss Hanacher was already grown and old, and she wasn’t anybody’s mother.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now