For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My accidental career as a part-time model and part-time pornographer for Oui, a men’s magazine, paid the bills, including my half of the rent on the Art Nouveau apartment my illustrator boyfriend Michael and I now shared, and I was even stashing a bit of money in my bank account.

I had enough saved that after two winter-y months of dragging my modeling portfolio through Chicago blizzards and howling hawk wind, showing up at go-sees with chapped cheeks, runny mascara and frozen feet, I put one of those icy feet down and told Michael we had to take a vacation someplace warm, like the rest of civilized Chicago did. Michael looked horrified at this extravagance; I don’t think his own parents, who had met in a camp for displaced persons at the close of World War II, ever took Michael and his brother on a family vacation.

“I’ll pay for the whole thing,” I mollified him, and set about looking for the cheapest tropical vacation package I could find. A sympathetic travel agent sent us to a “resort” on a tiny off island of the Bahamas, a trip that required one jet, one Piper Cub, and one ancient powerboat that chugged for hours through the waves at the perfect angle to completely soak us and our luggage.

Cheapskate Key had a tetherball, a small sailboat, and a bar. The tetherball and Sunfish were included with the price of the room, the bar was not. The bar was where Michael retreated, after getting smacked in the face with the tetherball, stranded out in the ocean on the Sunfish (that was my fault, how hard can it be to sail a little boat, I thought?), and being sick to his stomach at the only tourist attraction on the island: watching the fish cannery dump its chum into the shark-infested waters at sunset.

By the end of the week, I was tanned and rested, Michael was pale and suffering from a seven-day hangover and anxious to get back to work and his kids. He had run up a stupendous bar tab. One by one, I tore out all my American Express travelers’ checks, signed them, and handed them over to the hotel manager. “Do you have any money?” I asked Michael, who pulled out a few crumpled ones, which got us on the airport bus to the El and then back home to Burton Place, where Michael swore he would never leave the city again.

Winter eventually eased Chicago out of its icy grip, and spring and summer smiled on the new lovers. Michael and I were creating a sweet, cozy life together, tucked away in our Hobbit apartment. We were much richer in love than money and rarely went out, even for a cheap curry. I tried to make us romantic dinners in a kitchen that contained a sink, a small fridge, and a stove, but absolutely no counter space, drawers, or cabinets. I guess artists are not supposed to cook.

At night, Michael searched the Chicago TV stations for old black and white movies; he was a great fan of Frank Capra and cried every time he heard Jimmy Stewart say, “Zuzu’s petals.” We cuddled and kissed on the sofa, watching Mr. Deeds go to Washington or Sergeant York go to war or Lillian Gish and Robert Mitchum face off in The Night of the Hunter. My young dream of love, being half of a couple that needed nothing and no one but each other, had come true, except it was with a different Michael.

I was finally allowed to meet Michael’s kids who were both adorable moppets, even though the younger kid left the front door open and my little Yorkie Groucho ventured out into the Chicago night, never to return, and the older one took my bike out for an unauthorized spin, making it less than a block before a bigger kid shoved him off and stole it. All was forgiven. I was crazy about their father, whose “I love yous” and kisses soothed and tingled me at the same time.

In the midst of all this bliss, on a day I thought I looked especially cute in a Betsy Johnson pink-flowered minidress bought from a toothpick-chewing guy who sold designer clothes out of the trunk of his car, I flounced into the Oui offices to drop off my newest brilliant submissions and pick up a small check. The moment I walked in the door, I intuited something weird in the atmosphere, like the oxygen had been sucked out, or someone had set a small fire. Everyone in the office had a different odd expression, from grim death on the secretaries’ faces to editor Gerald Sussman’s ape-like grin as he bounced about on his tiny feet.

John beckoned me into his office. “We’re moving to Los Angles,” he said.

“Who? You? Oui?” I sounded like a deranged songbird. “What’s happening?”

“Everyone’s going. Well, the editors, art directors…” John rambled on, stacking up papers without looking at them, talking about how unhappy his wife was about leaving her friends and her family, how he’d have to buy a car, find a place to live. He worried if there were any fellow poets in L.A., that most unpoetic of cities, or just television studios and endless freeways.

Yes, yes. But what about me?

“I can still write for you though? We could mail stuff back and forth?” I tried to plant a look on my face that was both writerly and too cute to turn down.

John shook his head. “Not going to work. It would take too long, everything’s going to be crazy after the move…”

I handed him my hysterically funny short humor pieces, my best yet, and hoped that he would wait until I left to toss them in the bin. John found my check in a drawer and said, “I’m sorry.”

I autopiloted the walk home, my head full of mental arithmetic and plans: how much money was in my bank account, rent, electric, phone, what conventions were coming up, what photographers I hadn’t seen for a while.

Big events in my life never arrive by themselves, they insist on bringing along a friend.

My news — no more writing assignments, no more Oui modeling jobs, and we can say goodbye to our pal and neighbor, George, who was headed for L.A. with the rest of Oui’s art department — went unheard by Michael, who was waving a letter in my face.

“Esquire! Esquire magazine! They want me to illustrate Harry Crews’ column!”

Crews was a southern humorist who wrote about moonshine, coonhounds, hunting for squirrels, and bass fishing; his column in Esquire was called “Grits.”

Michael was a Chicago Jew who hated the outdoors, was afraid of trees, and had never seen a grit. Somehow an art director had decided these two would be perfect together. Michael was holding a contract from Esquire for a year’s worth of illustrations.

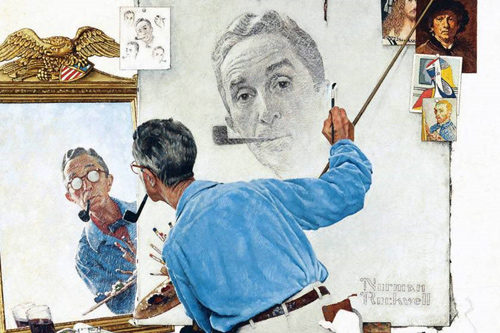

For Michael, this recognition from New York, from a magazine famous for its art and design, was the celestial sign he had been waiting for all his life, the confirmation he was following in the footsteps of his idols, Norman Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker.

I was so happy for Michael that I could put aside my disappointment at the early death of my own writing career. After his first burst of exhilaration, however, Michael turned moody; one day I caught him brooding over a drawing, pencil posed unmoving over the paper, sad songs from Derek and the Dominos filling the apartment.

“C’mon,” I said as I kissed and stroked his balding head. “Let’s go out! Indian food. My treat.” I got a mumbled “Okay,” and Michael flipped the record over and went back to not drawing.

It was not the romantic, celebratory dinner I had imagined. The curry house was our special place, where I had first realized that I had fallen in love with this funny looking guy who made me laugh and claimed to adore me. He didn’t look so adoring now, as he shoved his vindaloo around his plate with a piece of naan and called the waiter over for his fourth Kingfisher beer. My attempts at happy conversation fell flat. I ate, and Michael drank in silence until he announced, “I’m moving to New York.”

Why was everything and everyone leaving for the coasts, after Chicago had finally generously bestowed on me a boyfriend, a semi-steady income, and a love nest apartment that was like living in a work of art?

“And me?” was my first and only thought. “Am I going with?” I asked.

Michael looked down and said, “I don’t know,” which was not the answer I had hoped for. My eyes prickled; I felt betrayed and angry and abandoned. In my mind I was shouting, “I didn’t want this! You wanted this! You told me you loved me!” but “I don’t understand,” was all I could say.

Michael did not understand either. We spent miserable hours that night plumbing his swirling thoughts and emotions: He loved me, felt desperately guilty about leaving his kids; he was worried about earning enough to pay child support and live on; he was moving to an unseen studio apartment sublet from a friend of a friend; and back, always returning to “I love you Gay, it’s just…”

The bottom line was he had to move to New York. That was all he knew and all he could deal with at the moment. We did not talk about my own crushed and battered feelings. And I was too self-centered and selfish to understand how leaving his adored children to follow his art was tearing Michael apart; his separation from his sons would be a wound he never recovered from. How could he leave his kids in Chicago and take his Playboy model girlfriend with him to New York?

In between our unhappy discussions of his tortured psyche, Michael packed up his apartment and said goodbye to his kids, weeping harder than they did and promising to fly them to New York as often as possible. I wandered up and downstairs, trying to stay out of the way of this family disunion. I picked at the few possessions I had kept with me over all the moves of the past three years and wondered what to do next. It would break my heart even more to live with just the memory of Michael in that magical Burton Place apartment, even if I could have afforded it on my own.

Suddenly I didn’t want to be in Chicago at all. I didn’t want to drag my portfolio around town in the freezing, blustering winter and the soupy, sticky, summer, or fight off handsy photographers, or murder my feet standing for hours on the cement floor of the convention center passing out brochures for power tools.

I called my old friend Mindy in Minneapolis, gave her my abridged story, and asked if I could stay with her for a few weeks.

I had last seen Mindy on her one and only visit to Chicago when I was still living with James, whom she took a deep dislike to after he offered her a Quaalude while I was in the shower and hinted that a threesome would be fun. Since then we kept touch through sporadic phone calls and lines scribbled inside funny greeting cards.

My friends are all generous spirits. Even though we had not spoken for months and months, Mindy said yes, come on up, she had room for me.

Michael and I said our goodbyes amid floods of tears. “What the hell am I doing?” Michael wept. I wondered that too. I gave him Mindy’s phone number and address and we parted, Michael off to conquer the illustration world in New York, me to do who the hell knew what in Minneapolis.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Ah. So many feelings for you. The move back to Minneapolis didn’t surprise me.

Uh oh, this chapter left me with more sighs than chuckles… I had not expected the depth to which you had fallen in love. Yet, now I feel strangely guilty for missing it.

Cue the Carole King soundtrack. So far away…

I wonder what happened to Groucho? Poor guy.

I am astounded by your choice to depart to Minneapolis.

I feel this so hard.

I too had my heart broken by a guy who left for New York, years and years ago.

I still remember all the tears as he got on the Greyhound bus.

But back to Minneapolis?? Can’t wait to read next week’s chapter!

Lookslike things were pretty rocky for you in this chapter Gay, even though they seemed calmer and more ‘normal’ at first. You had a good thing going with your gigs at Oui magazine, then they moved to L.A.

I don’t fault you at all for asking “what about me?” First the Oui team, then Michael leaving for New York. I gotta give him credit for aiming to be the next Rockwell or Leyendecker, even if it’s unrealistic. Aim high to help offset life’s lows.

You’re at a crossroads again. Hopefully you’ll find a new man with Michael’s aspects you like, but without the baggage (children). Before that though, a good job. Glad you kept in touch with Mindy and she has a place for you to stay. Fortunately she didn’t hold James against you. Quaalude’s. No shock there.

This might be a good time to look up those other girls you palled around with in that big white car several years earlier, and see what they were up to in in the mid ’70s for some networking.