For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

My second Michael, my second true love, had tossed me to the wayside; I was too much baggage for him to handle on his pilgrimage to New York City in pursuit of his art. I was rescued by my Minneapolis pal Mindy, who had been my travel companion on that fateful Spring Break in Mexico.

After years dedicated to serious partying, Mindy had finally given herself a good shake and found her way back to college; she was taking classes during the day and waitressing at night. Mindy’s roommate was gone for the summer, so I would take over her tiny bedroom until she came back.

I dropped my two suitcases holding all my worldly possessions, fell into Mindy’s arms, and had a good cry. Mindy blotted my face with her waitress apron and said, “It will be fine. You will be fine. No more crying.” I gave her a trembling smile as she headed out to work and ordered myself to do all my heart-broken sobbing in bed or in the shower, anywhere Mindy couldn’t hear me and pity me.

Most of the time Mindy was gone, off to class and work, and I was left alone in her small but light-filled apartment. I spent my first days sprawled weepy on the couch, all the more sorry for myself that I didn’t have a single one of Michael’s blues albums to listen and cry to, songs of betrayal and abandonment, of false-hearted lovers, songs that would let me wallow in my sorrow. Eventually I gave myself a good talking-to and ventured out into the only thing that could soothe my ruptured soul, my favorite thing in the world: a Minnesota summer, balmy languid days that last till nine, when the sun finally says good night and sinks away.

Mindy lived a short walk from my beloved, glorious Lake Calhoun (now known as Bde Maka Ska), a just-right-sized expanse of sky blue water dropped in the center of Minneapolis. Lake Calhoun was surrounded by the softest grass, the leafiest trees, and had a tiny sandy beach with a lifeguard chair, rowboats to rent, and a snack bar.

I could have registered for fall classes at the University of Minnesota, I could have looked for a job, but I was mesmerized by summer, as sweetly familiar as a favorite childhood book and as fleeting as a dream. Chicago summers had been all sweat and steam and stink; here in Minneapolis I could dip in the lake during the day and slip into a sweater at evening.

I read whatever magazines and books were lying about Mindy’s apartment, swam in Lake Calhoun, and tanned on that little stretch of sand, lunching on Popsicles from the snack bar. I watched couples making out on blankets and cried as only a jilted young lover can cry. I made sure there were chips and bread and cold cuts and six-packs of beer in Mindy’s fridge, and ignored my dwindling savings that I had no prospects for replenishing. I waited for the phone to ring.

The phone did not ring, but a three-page letter from Michael arrived. Most of it was on the wonders of New York City: The art museums, the Modern, the Guggenheim, the Whitney, and the Metropolitan where you could pay just a penny to get in. The subway, which, unlike Chicago’s El, actually took Michael everywhere he wanted to go, once he figured out the confusing lines and local versus express stops. The dozens of different languages Michael delighted hearing on the street every day, the sneaky thrill he got eavesdropping on the German or Russian or Yiddish speakers. His sublet’s neighborhood of Greenwich Village, where there were jazz and folk and blues clubs, and outdoor cafes on every corner.

It was the Summer of Sam, the summer of the Bronx burning, of the hot August night of blackout and looting, the summer New York City teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Michael was oblivious to the dangers, the dirt, the looming disasters. “You would love New York,” Michael wrote, “and I miss you so much.”

I wrote back, mostly about how much I missed him, as I had no other news outside of what flavor Popsicle I had eaten for lunch. Our letters criss-crossed the country, full of love and longing. I read Michael’s letters aloud to Mindy, always a sympathetic ear, on the few nights we spent together. She sipped the beer I gratefully supplied and flipped through the magazines she never had time to read.

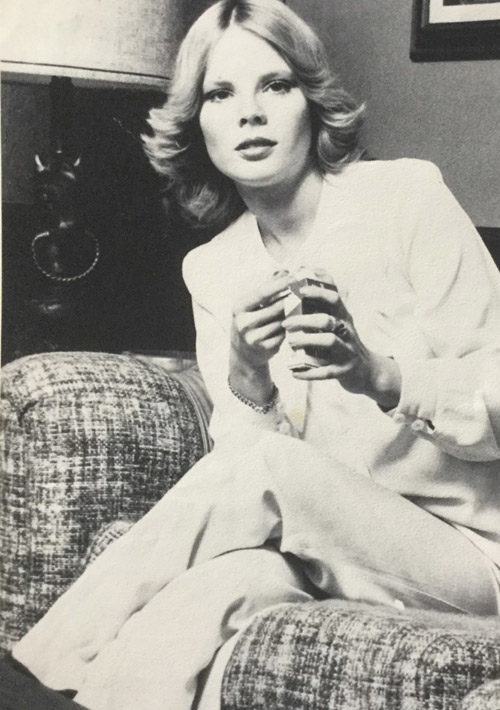

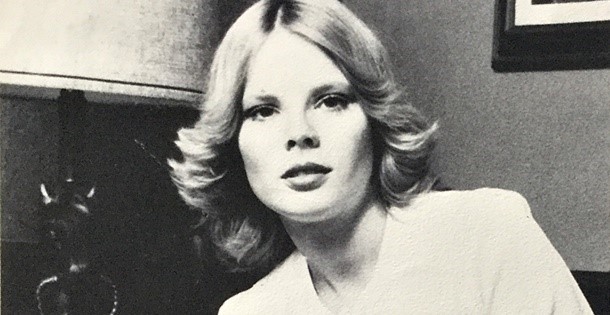

“You’re going to New York,” Mindy assured me. “Wouldn’t it be cool if you got a job here?” and she held up the latest issue of Viva magazine, with the pouting face of minor starlet Barbara Carrera on the cover.

As Mindy predicted, the long-distance call and the summons to New York finally arrived. I heard Michael sniffling, he had a catch in his voice. “I am so sorry, I don’t know what I was thinking of, I love you, I want to be with you, please come to New York. The place I’m staying in is really small, I’ll find someplace for the two of us, it’s going to be great, please say you’ll come.” A tsunami of joy washed over me and I started to cry too. I had missed Michael dreadfully. For weeks my mind and heart had been unmoored, drifting through the dark seas of rejection and loss. Now I was rescued, swimming toward a lifeboat of love, Michael holding out his hand to pull me in.

I opened my pink Samonsite suitcase to pack up the bikinis and cutoff jeans I had been living in, and there on the top was my modeling portfolio. I leafed through the acetates holding the garishly lit and cheaply printed photos of me in surgical scrubs or lounging on a hideous “Rent-to-Own” plaid couch or eating a McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish, my own mouth gaping like a bass, and knew I had zero chance of finding modeling work in New York. I had to get a job, and the two skills I had were waitressing and magazine writing.

Under my modeling portfolio was a manila envelope with everything I had written for Oui. I sat on the floor and replaced all the photos of me with these short humor pieces and girl sets, placing the few that carried my byline at the front, and the most titillating girl-on-girl photos at the back of the portfolio.

A silvery bell of an idea popped into my head. I picked up the phone and called Los Angeles, mentally promising Mindy a few extra beers. I got my old Oui editor, John Rezek, on the phone and made quick work of the how-are-you small talk; it was long-distance daytime rates and I really didn’t care how much progress had been made on his epic poem about the first dog in space.

I said, “I’m moving to New York. I want to find a job at a magazine. Do you know anyone I can send a resume to?” John didn’t. He had never worked in New York. But Oui editor Gerald Sussman had, and he was standing right there. John put Gerald on the phone.

“Hi Gay, yeah listen, give Gordon Lish at Esquire a call. We’re great friends. Just mention my name and he’ll see you, help you out.”

Gerald’s connection at Esquire, the same magazine that had lured Michael to New York, was a good omen, a blessing on my next move to Greenwich Village and into what had to have been the Guinness World Record’s smallest studio apartment. It was in a brick building on West 10th Street, which confusingly runs perpendicular to West 4th Street. Michael’s sublet was a single room that held nothing but a convertible couch; we when unfolded the bed (which we did immediately) it took up the entire space, wall to wall. The bathroom had a shower, sink, and toilet you had to sit on sideways if you wanted to close the door. The kitchen was an alcove where a half-size two-burner stove and dorm fridge huddled against a sink, lit dimly by the apartment’s only window, which had never been washed and overlooked an airshaft. It was still the perfect cozy nest for reunited lovers, but if two people had to share it indefinitely, there would be knives at the throat. Michael said, “It’s just till the end of the month, then we’ll move into a bigger place.”

In the still light and sultry September evening, Michael walked me up Eighth Avenue to Chelsea, which was all bright, cheap Cuban-Chinese restaurants, a long-gone cuisine that specialized in ropa vieja and fried rice. All along the side streets, card tables, folding chairs, and wooden crates were set up for what Michael told me were never-ending domino games; each game had twice as many kibitzers as players. We turned left on 20th Street and threaded our way through the domino tables to the middle of the block. Michael held me by the shoulders and placed me on the far right of an iron gate to peer inside past the grey stone front building. “See the courtyard?” he asked. “We’ll be living in the carriage house in the back. It’s called a mews.” Carriage houses and mews sounded so romantic we had to hurry back to the love nest, promising ourselves that we would come back to dine at La Tas de Oro or Mi Chinata as soon as we could afford it.

Financially, we were running on fumes. I had left Chicago with $800, which had been drastically reduced by thank you groceries for Mindy, rowboat rentals, snack bar Popsicles, and a plane ticket to New York. Michael was broke; landing that Chelsea apartment (monthly rent $400, the same amount as James’ luxury high rise back in Chicago) had required two months’ security, plus electricity, phone, and cable, which Michael had balked at until he discovered that no television in Manhattan could get reception without it, and Michael needed old movies and the National League.

The day after our lovely, loved-filled reunion, I invested in a stack of likely magazines and a ream of typing paper, balanced my trusty Smith Corona on my knees, and started sending resumes and cover letters out into the void, addressed, as John Rezak had advised, to each magazine’s managing editor. While I typed, Michael perched next to me on the folded-up couch, drawing board across his lap, cross-hatching an illustration for the next Harry Crews column; this would bring in $250, which was exactly what Michael had to pay out in child support.

“I’ll waitress,” I told Michael. “I’ll waitress until I get a real job,” positive that within a month or two I would be snapped up by a magazine. It turned out that it was harder to get a waitress gig than land a job in publishing. Every Greenwich Village bar and restaurant recognized me on sight as a non-New Yorker, and therefore a rank amateur. I never even got to fill out an application. The manager would say, “Where was the last place you waitressed? Minneapolis?” as if my last job had been slinging goat curry in Karachi. I was even rejected at every single one of the Village’s coffee shops, whose owners thought delivering a fifty-cent cappuccino to a table was beyond my capabilities.

It took me a week of non-responses to my resumes and being given the bum’s rush at bars before I worked up the desperate nerve to cold call Gerald Sussman’s friend. I gave myself a pep talk: I could do this. I had banged uninvited on the doors of dozens of photographers. I had threatened a receptionist with a can of Reddi-Whip. I had smuggled drugs from Mexico! I could phone a perfect stranger and ask him for a job. I called Esquire and was connected to Gordon Lish, who like everyone else in the world back then, picked up his own phone. “Hello?” said a plummy voice. I took a deep breath.

“Hello Mr. Lish, my name is Gay Haubner and I was a writer for Oui and Gerald Sussman told me to call you to see if I could interview for a job at Esquire.”

I sounded like a squeaky cartoon mouse rushing through a nursery rhyme at a recital.

“Well,” Gordon Lish drawled. “Then I better see you. Come up tomorrow at eleven.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Nice! As usual, you end up on your feet.

No time to comment: I’m dying to see what happens st the Esquire offices!!!

So THIS is how you ended up in New York! Or is it?? Did you leave and return? Did you write for Esquire?? Did you move to the mews??

I knew Michael would come back. They always do.

Can’t wait to read next week!

Hi Gay,

Still here and reading, and its 102 today in Mpls. Too hot to sit out on the beaches today.

Ah Cafe Reggio- one of our favorite spots to go when we get to NYC!!

I had no idea there was a lake in Minneapolis and I have been there! Each chapter is more marvelous than the one before. I wish every day was Thursday.

It must have been a typo, but it is “La Taza de Oro” (The gold cup) one of my favorite rice and beans joints. I wonder if it still there, 8th Ave between 14th and 15th.

Let’s see how this all plays out in chapter 59. Reaching people on the phone is nearly impossible now, like the call to Gordon at the end of this chapter. ’77 was one of THE last good years for Esquire. I have the Mary Tyler Moore (newsstand) issue from that year—still beautiful.

You just need some good breaks that will last so you can really reach your potential. Mark Ryan, good to hear YOUR updates on Minnesota. GP, if what you ask happens, it surely would be the first and last time it ever did!

Making those kinds of phone calls were always nerve-wracking for me. I hated making them even if I had a reference, which of course is always an edge. I was happy that you made a short detour back to Minneapolis (considering the title of this memoir). Today was the kind of Minnesota summer day you mention in this chapter and would have loved. After I finished reading it I felt compelled to take a spin on my bike around the lakes (Harriet, the Lake Formerly known as Calhoun, and Lake of the Isles). Beautiful night, with pleasant temp and moderate humidity. Friday, however, the forecast is for 96 °F with oppressive humidity and a heat index of 105. An escape back to Duluth is on the agenda for the weekend.

A phone call, a fortune stroke of serendipity, and thank goodness fate deemed you unworthy of NYC waitressing. Now will Gay Haubner meet Gay Talese on Gay Street?