This article and other stories of the Civil War can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Saturday Evening Post: Untold Stories of the Civil War.

—This account appeared in the July 22, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

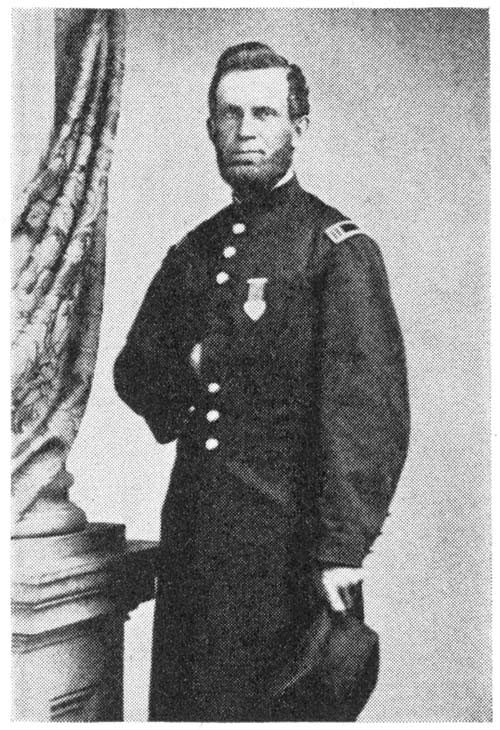

For two memorable, action-packed months in 1863, 19-year-old Lucy Bundy Cobb found herself caught up in the crazy whirl of the Civil War. She hurried from her home in Ohio to Winchester, Virginia, to nurse her ill husband, a Union officer. The Confederates seized Winchester and captured both of them. Lucy was sent to a prison in Richmond and exchanged without knowing her husband’s fate. A keen and sensitive observer, she related her experiences in later years to her son, Howard Bundy Cobb, and a grandson, retired Col. Ralph C. Benner. Cobb wrote down her story and Benner preserved the manuscript, giving us a rare and exciting insight to Civil War life and adventure.

* * *

In the telegram the colonel commanding the 116th Ohio Volunteer Infantry requested that I come at once. My husband and other officers had typhoid fever, and nurses were needed badly at the hospital in Winchester, a Virginia city which our troops had occupied.

At the head of his own company of recruits, John Haskell Cobb had left me on our farm in southeastern Ohio scarcely a year before. With the help of an occasional old man or boy, my Aunt Sarah and I had managed to put in a crop to feed ourselves and our livestock.

My father, Congressman Hezekiah S. Bundy, hurried up the path to our farm cottage as soon as he learned of the telegram. “Lu,” he began fussily, “get ready immediately. I must go back to Washington soon anyway, and will take you directly to the Secretary of War for authorization to join your husband.”

Hurriedly assembling what few clothes I found suitable, I clambered into father’s low-swung carriage. The going was slow, but we finally boarded the smoky old railway coach and patiently slept in our seats through the night trip to the capital. The next morning found us in the office of the Secretary of War.

The voice of Secretary Edwin M. Stanton seemed to come from the depths of his iron-gray beard. “Congressman Bundy, I’ll grant this pass for your daughter, but if she were my daughter, I’d send her home. Too many officers’ wives are going to the battle front. A girl of 19 should be far from the scenes of war!”

Vividly the words of that telegram came to me, and my face must have changed expression. “No, no! I cannot turn back now. John needs me. I must go!” My voice evidently held a pleading note, for the Secretary of War grimly signed his name to a paper which he handed me. “May God be with you,” he said gently. Then, turning away hastily, he seemed to dismiss me to a foolhardy venture.

I was wholly unprepared for what I was to find in Winchester. This little town in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley changed hands between the North and the South many times during the war. This morning, however, it lay calmly in the sun under the old Star Fort whose earthworks frowned down on the cluster of cottages where the Union Army had its headquarters.

No one received me at the dwelling where I dismounted from the stage and struggled with my carpetbag. And my knock received no reply. The front room was evidently an office, so I ventured timidly into the house. From the rear I heard a sound which filled me with misgiving. Dropping my bag, I hastened in the direction of that feverish moan.

“John!” I cried, only to receive a vacant stare as he tossed about in bed in a tangle of sheets. My heavily bearded young husband had lost many pounds. I seized his weak, thin shoulders, pressing him back gently onto the none-too-clean pillow. He yielded to my ministrations without giving a sign of recognition.

Anxious days followed. John lay feeble and helpless, feverishly trying to lead his men against imaginary breast-works manned by “Johnny Rebs” blazing away. It was a lengthy vigil. But when John’s eyes opened with awareness and he murmured, “Lu!” the weak smile with which he greeted me left me breathless. The tension was broken. Tears came to my eyes for the first time, and I sank down on the bed in relief.

John was soon sitting up, but I kept close to my convalescent husband. Soon the rumblings of war drew nearer. The Confederate Army, if not blocked, would soon engage Star Fort. Our entire regiment was thrown into action.

For hours the din of battle kept coming across the brow of a nearby hill. Soon noncombatants and stragglers entered town, bringing to me a glimpse of the meaning of war. As evening approached, I became prepared for most any eventuality. There came an order to all noncombatants. “We must go up to the fort,” John announced.

Star Fort was nothing more than a hollowed-out earth-works on the brow of a hill overlooking Winchester. Noncombatants huddled in one corner. Gunners and swarms of infantrymen milled about in confusion. We watched apathetically while the Union flag was lowered from the main staff. I experienced a feeling of helplessness as a white cloth was run up in its stead. The firing ceased. Columns of troops marched out in surrender. Then there appeared the first gray uniforms I had ever seen. Where Old Glory had waved but half an hour before, we watched the Stars and Bars rise! I looked from the flag to John’s face for reassurance. There was none. Instead, with compressed lips, he handed me his watch. “Here, Lu,” he said tonelessly, “hide this among your petticoats. No rebel shall wear it. Smuggle it through the lines when you are exchanged.”

“John! We are not to be separated,” I cried, clinging to his sleeve. “I’ll not leave you here.” Then several other facts became clear to me. “Is there danger of you being sent to Libby Prison?”

Very soon, several Confederate officers came up and said all women would soon be transported to Richmond.

I rushed back to John, bursting into tears. That awful name “Richmond” filled me with such fright that I closed my eyes and hid my head on his shoulder. I was still clinging desperately to him when a rebel private soldier forcibly but gently released my grasp, saying, “Sorry, lady, but it is the captain’s orders. You need have no fear of us Southerners. We never hurt a lady.” John, weak and pale, let his arms fall to his sides. He swayed and nearly fell.

Common transport wagons, pulled by four horses, were ready for us. Sitting on straw on the wagon floors, we journeyed for long, weary days into the South. Our greatest concern was for food. As it was next to impossible to obtain fresh food, offerings from charitable Southerners along the way were welcomed. At one village where the women appeared particularly desirous of giving us food, however, they did it in a surly manner with many an ugly curl marring the symmetry of a pretty lip. The sandwiches looked good and fresh. The bread was clean and handed us in clean paper. But intuition filled us with suspicion. We noticed the younger women and children, particularly, gazing at us as if expecting some demonstration. There were facial demonstrations very soon. For when we half- famished women bit into the sandwiches, we discovered the bread had been spread with soap! The Southern women screeched and howled with amusement as we threw the bread away, violently wiping out dry and soapy mouths. The guards, however, were more than apologetic for the shameless womenfolk.

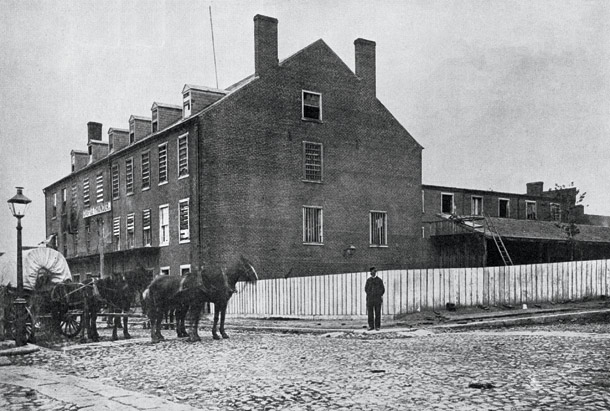

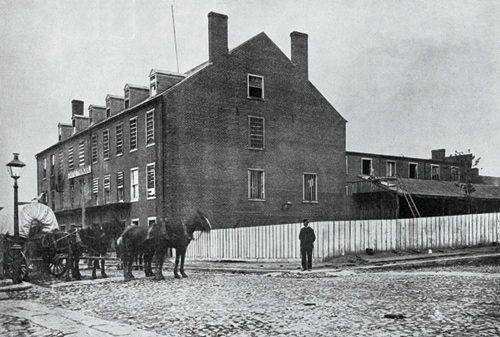

Finally arriving in Richmond, we were taken directly to an old tobacco warehouse across from historic Libby Prison. From the barred windows of our jail, nicknamed “Castle Thunder,” we could see Union soldiers pacing back and forth in old Libby, where I was fearful John would eventually be imprisoned. Days of idleness followed.

On the 14th day, word came that our exchange had been effected. No group of prisoners was more grateful for freedom than we Northern women. But our preparations were marred by wistful glances across at grim old Libby. Perhaps our husbands languished behind those ugly walls.

Aroused at 2 a.m. on a June day in 1863, 42 women prisoners were marched down the three flights of rickety warehouse stairs, out into the dim light of Richmond streets, to the bank of the James River. A makeshift bridge of two planks led over the murky water to the boats. Once safe on the opposite shore, we boarded a flag-of-truce vessel and steamed by way of the James River, Chesapeake Bay, and Potomac to Washington. Finally, I was allowed to go to Pittsburgh and then home.

I arrived at my destination with mixed feelings. For a moment I was glad. Then it came to me with a rush that I had failed! I had gone to bring back my sick husband. And here I was on the threshold, empty-handed. Aunt Sarah said nothing about John, and I was grateful. Soon I went out to the pasture where the farm horses grazed contentedly. My mare Polly loped over to me, thrusting her nose in welcome. I felt comforted. I tried to shut out the memory of war and was thankful that my Polly never would sniff burnt powder or hear the whiz of a Minié bullet.

On my third day at home, a disturbing conversation took place. Aunt Sarah, after talking with someone who paused outside her window, asked me, “Had you heard? Morgan’s Confederate raiders are coming up the river valley.”

My heart sank. “You don’t mean that his horsemen may overrun this farm! War does things to peaceful homes in the South. Surely we in Ohio are not faced with that kind of devastation!”

Soon a crowd of women gathered in the yard, evidently to see me. Many were wives of soldiers whom John had enlisted in his company. In the vanguard was Sally Saxe, whose husband I had last seen in the dim twilight of the Star Fort at Winchester, supporting my swaying John.

“Lucy,” Sally said anxiously, “you know about war. What air we goin’ to do? Morgan’s men may be jist over the hill. I’m scairt to death!”

I put a reassuring hand on her shoulder and spoke to the crowd. “Neighbors, the Confederate soldiers are not bad. I spent two months among them and they do not make war on women and children. They may take our feed and even our livestock, but they will not hurt you.”

Sally and some others were not convinced. “They may burn our houses or carry us off!” she wailed. Others joined in the cry.

By the next dawn, gray horsemen appeared from all directions as if they had dropped from the skies. Gen. John Hunt Morgan, a dashing cavalryman with a full mustache and pointed beard, rode up to the farm majestically. He quartered a detachment of men overnight in our barn. Soon I heard a firm knock at my kitchen door. It proved to be one of Morgan’s officers.

“Madam, have you flour in your house? You have some hungry visitors. We’ll have to ask you for food.”

I answered him calmly, in a tone as neutral as possible. “Yes, sir, I have flour. How much of it do you want?”

Removing his hat, he appeared embarrassed. Then he explained. “You see, lady, actually we can’t use flour. We are asking you to bake us a batch of bread — a big batch, all the flour you have in the house. We are hungry and we are living off the country as we go.”

“Very well,” I answered, “but it must be made from biscuit dough. There is no time for yeast bread.”

“Thanks, lady, any kind of bread will do.” The soldier smiled appreciatively and backed away. However, I saw him eying our speckled hens and broods of fryers, and surmised correctly that they would disappear before morning. We baked bread until our backs felt broken and the larder was almost empty — all but what Aunt Sarah had grimly secreted in the attic. She planned not to starve.

Yet it was a relief to be left some property. I began to feel safer, when a commotion in the barnyard brought back all my dread. Three burly soldiers closed in on Polly and slipped a rope over her silky neck. I grabbed the rude halter and turned wrathfully on the three men. “You can’t have Polly!” I stormed. “Let go that rope. Let go, I say!” As I jerked the rope away from them, a sergeant came up.

“But, lady,” the sergeant began apologetically, “General Morgan gave orders we were to take all sound horses we needed, and no mere woman can interfere with us. We are not taking your farm team. We want only the mare and are leaving this Thoroughbred in exchange. He has a sore back and needs a long rest.”

I looked where he pointed. There, standing dejectedly, was a handsome Kentucky gelding, a standard-bred horse whose coal-black coat glistened in the morning sun. I reasoned that there was little I could do against these marauders. Sadly and slowly I released my hold on Polly and suffered her to be led away.

* * *

One morning, Ronald Saxe, Sally’s son, came up and burst out “Pa’s home!”.

As his father had been captured with my John, I grabbed his shoulders. “Why didn’t my husband come with him?” He hesitated. I shook him.

The boy broke into a stream of words. “Pa said he and Cpt. John slipped out of the prison stockade at Winchester the night after you left for Richmond. They got clean away and struck out north as fast as the captain could travel, hiding daytime and walking nights. They forded or swam rivers until they got into Ohio. They rested some and foraged for food too. Then they heard about Morgan’s raid. The captain insisted on going to head off the rebels. They crept up close to one of the rebs’ advance amps below Pomeroy at night. And what do you think? There was Polly, tied to a tree with some other horses.”

“The captain vowed he’d get Polly away from the rebs. Pa couldn’t stop him. That night, the two of them tried to steal Polly and another horse. But Polly gave them away. She neighed when she smelled familiar folks, and the guards pounced on them. They soon found out that your husband was a captain in the Union Army. So they held him. Gen. Morgan, they said, isn’t letting Yankee officers go because they are valuable for exchange. They let Pa go.”

I burst into tears. The boy stole silently away as if he had been guilty of some crime. The slow, creeping paralysis of war was enfolding us. Hours seemed to pass. Suddenly Pvt. Saxe and wife Sally rushed up to the door.

“Morgan was captured not 20 hours after he turned me loose,” Saxe shouted. “There is a chance that his prisoner detail never got back across the Ohio River,” Saxe explained. I sat silently, too tired to think. My gaze wandered out over the field and down the valley road. Suddenly my eyes became riveted to a familiar moving object. I got to my feet and advanced instinctively to the gate.

In a lather of foam, panting with her nostrils aquiver, Polly came to a stop. Her rider flung himself from the saddle. The mare stood motionless while my soldier husband gathered me into his arms.

“Lu!” he cried brokenly, while I could only reply, “John!”

— From “One Woman’s Ordeal,” from the July 22, 1961, issue of The Saturday Evening Post

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now